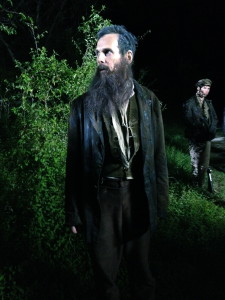

Above, Richard Brooks as Frederick Douglass, Thomas Coleman as Shields Green, T. Ryder Smith as John Brown.

Excerpts from the reviews

Full reviews are below

“A reminder for our noisy, instant-news present that the great movements of history, whether for civil rights or equality for women or the rights of people with disabilities, take decades to mature, and that presidents and other politicians are often among the last to board the bandwagon. . . . The program, so rich in well-staged re-enactments that it is more docudrama than documentary, traces the abolitionist movement across almost 40 tumultuous years, a period of colliding worldviews that makes our current polarization seem slight.”

– Neil Genzlinger, New York Times

“Anyone who has ponied up to see “Lincoln” really needs to tune into the “American Experience” three-part documentary “The Abolitionists.” . . . a much more inclusive depiction of how slavery came to be outlawed in this country. . . . “The Abolitionists,” being only a three-part endeavor rather than a Burnsian epic, is forced to ignore many notable abolitionists . . . Fortunately, director Rob Rapley wields the few he has chosen wisely, to reveal not only the relatively small world of the anti-slavery community but the decades-long grind of working against a society and government that seemed perfectly willing to allow the United States to remain a slave nation forever. Small gains were inevitably answered by large setbacks as the politically powerful Southern states pushed back with a largely pro-slavery federal government. . . . It is a moving and emotional documentary . . . ”

– Mary McNamara, Los Angeles Times

“Vividly recreates and recounts the interwoven lives of its subjects, beginning in the 1820’s until the end of the Civil War . . . Abolitionists not only had sticks and stones and bricks hurled at them, but were also called many names: radicals, agitators, trouble-makers, and nigger-lovers to name but a few. So publicly reviled they were, that the word “abolitionist” itself became an epithet. . . . It tells its story in a compelling manner—this reviewer watched all three episodes back to back and was never bored—and leaves viewers with a deeper understanding of the conflicting approaches to ending slavery in America. . . . The format is well-trod ground: narration while old photos and documents fade in and out; dramatic re-enactments of some key events; commentary from a few historians. This recipe has proven successful many times, and it works particularly well in this series. The “talking head” sequences are well-spaced throughout instead of dominating the production, and what makes The Abolitionists so watchable is the acting by those portraying historic figures . . . ”

– Gerald D. Swick, HistoryNet.com

Video

Offscreen

Above, “Offscreen”, from top: Director of Photography Tim Cragg, left, director Rob Rapley, center, and Richard Brooks, right; Rob Rapley, left, costume designer Deborah Newhall, T. Ryder Smith; T. Ryder Smith; shooting in New Castle, DE; on location outside Richmond, VA; outdoor sets in Richmond, VA; T. Ryder in barn as chickens are wrangled; in costume in Richmond, VA; with beard in Richmond; New Castle, DE streets; Richmond, VA set; T. Ryder Smith, Kacy Gabbert, Rob Rapley, Denyse Ellington, Richard Brooks, in DE.

Full reviews

New York Times, Neil Genzlinger – Well Before Lincoln, Enemies of Slavery. Abraham Lincoln drew Steven Spielberg’s cinematic attention, but Lincoln was still a store clerk when William Lloyd Garrison published the first issue of the newspaper The Liberator in 1831, vowing to “not retreat a single inch” in his campaign to eradicate slavery.

“The Abolitionists,” a three-part “American Experience” that begins Tuesday night on PBS, is a reminder for our noisy, instant-news present that the great movements of history, whether for civil rights or equality for women or the rights of people with disabilities, take decades to mature, and that presidents and other politicians are often among the last to board the bandwagon.

The program, so rich in well-staged re-enactments that it is more docudrama than documentary, traces the abolitionist movement across almost 40 tumultuous years, a period of colliding worldviews that makes our current polarization seem slight.

The focus is on five prominent figures with a lifelong dedication to the cause: Garrison, Angelina Grimké, Frederick Douglass, Harriet Beecher Stowe and John Brown. That oversimplifies things considerably, of course — it takes more than five people to move a mountain — but the principals are well chosen in that they represent a range of approaches as to how best to rid the country of slavery. Garrison, at least in the beginning, thought words could do the job; Brown preferred the sword and the gun.

The first installment looks at the 1820s and ’30s, when the abolitionist movement coalesced and began to realize just what it was up against. Antislavery leaflets in the South were met with violent protests, which was no surprise, but Garrison and others were taken aback when ugly opposition also materialized in the North.

“The mobs shattered every abolitionist assumption: that righteousness would triumph over evil; that their fellow Americans would listen to reason; that their Northern neighbors would support the abolitionist cause,” the program’s narrator, Oliver Platt, relates.

Part 2 explores how war with Mexico in the mid-1840s accelerated the debate by raising the question of whether territory gained by the United States in that conflict would be slave or free. Douglass (portrayed in re-enactments by Richard Brooks of “Law & Order”) emerges as a major player, recruited by Garrison to speak across the North. His appearances put a face on what for many had been a theoretical discussion.

“Many of the audience members had never, ever seen a slave, let alone been to the slave South,” the historian Erica Armstrong Dunbar says. “So to have a person like Douglass gave the antislavery cause teeth. It gave it authenticity. It gave it a new voice.”

Meanwhile, Garrison (portrayed by Neal Huff) was beginning to despair that political bodies or other entrenched institutions would ever act against slavery, and his writings and lectures became more impatient. The ultimate champion of radical action, though, was Brown (T. Ryder Smith), who, as Part 3 begins, is killing slavery advocates in Kansas and then setting his sights on the armory at Harpers Ferry. In the program’s most evocative scene, he meets Douglass at Chambersburg, Pa., where Douglass tries to talk him out of the raid that would help push the nation to civil war.

“It will kill you, and it will serve no purpose,” Douglass says. “It will be a blood bath.”

To which Brown replies, “Without the shedding of blood, there is no remission of sin, Douglass.”

Lincoln turns up late, and in this telling he is a bit of a waffler, trying some appeasement strategies before eventually, 150 years ago this past New Year’s Day, issuing the Emancipation Proclamation. By this point in the program, the case has been made that war was the only way this defining issue would be resolved. But it was a long journey to get to that point, full of soul-searching, reasoned debate and not-so-reasoned violence. Food for thought for our contentious age, when discussion of perfectly solvable problems seems to turn inflammatory so easily.

1.7.13

Los Angeles Times, Mary McNamara – ‘The Abolitionists’ shows the people who led to Lincoln. Even as he helped orchestrate the American Revolution and the creation of modern democracy, John Adams worried that the framers of history, more interested in portraiture than landscape, would choose one or two individuals — Benjamin Franklin, George Washington — to create a mythology of supermen who single-handedly built a nation. For years that fretful insight proved true, and though Adams eventually got his due, it certainly applies to other moments of cataclysmic change, none more so than the Civil War.

Certainly in light of Steven Spielberg’s “Lincoln,” one could be forgiven for believing that Abraham Lincoln was the driving force behind the abolition of slavery in America. Yet even Lincoln admitted that he had been in danger of falling on the wrong side of the issue, politically if not personally, and that his actions were influenced by the relentless pursuit of justice by a group of Americans who devoted years of their lives to the abolition of slavery.

Which is why anyone who has ponied up to see “Lincoln” really needs to tune into the “American Experience” three-part documentary “The Abolitionists.” Though lacking the majesty of Tony Kushner’s script or Daniel Day-Lewis’ performance, “The Abolitionists” is a much more inclusive depiction of how slavery came to be outlawed in this country.

Written, produced and directed by Rob Rapley, “The Abolitionists” uses the now-standard combination of dramatic reenactments, photographs and narration to chronicle the rise of the anti-slavery movement in the United States through a handful of its better-known proponents. The story of William Lloyd Garrison provides the narrative spine.

In 1831, Garrison founded the Liberator, a Boston newspaper that became both a clearinghouse and platform for scattered abolitionists. Pious, pacifist and doing what he considered God’s work, Garrison had, nonetheless, a remarkably modern understanding of political celebrity. When Angelina Grimke, whose views caused her to flee the South Carolina home of her wealthy, slave-holding family, wrote an admiring letter to Garrison, he quickly realized the potential influence of an anti-slavery Southern woman and sent her on a speaking tour across the country.

Likewise, when the newly escaped Frederick Douglass told his story for the first time at a Boston town hall meeting, Garrison lost no time in encouraging the young man to use his gift for oratory to spread the truth about slavery. Douglass became Garrison’s protégé until student eclipsed teacher and the two men fell out, refusing to speak for years.

Harriet Beecher Stowe, the author of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” and John Brown, hanged for his unsuccessful raid on the federal arsenal at Harper’s Ferry, are also discussed at length. Stowe came to her anti-slavery views after the death of her young son; in her grief, she felt connected to the countless enslaved mothers separated from their children. Her book, written to ensure that her child’s death would bring about some good in the world, is perhaps the most influential novel in American history, and both Garrison and Douglass were, not surprisingly, early supporters.

“The Abolitionists,” being only a three-part endeavor rather than a Burnsian epic, is forced to ignore many notable abolitionists (Lucretia Mott, for example, shows up several times in a photograph but is never mentioned) and downplays the concurrent rise of feminism — many, including Grimke, Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton considered their work as abolitionists entwined with the cause of women’s suffrage.

Fortunately, Rapley wields the few he has chosen wisely, to reveal not only the relatively small world of the anti-slavery community but the decades-long grind of working against a society and government that seemed perfectly willing to allow the United States to remain a slave nation forever. Small gains were inevitably answered by large setbacks as the politically powerful Southern states pushed back with a largely pro-slavery federal government.

Although none but a few radicals like Brown had ever preached violence, much less war, it was the relentless demands of the abolitionists that slowly turned more and more Americans against slavery, allowed the election of Lincoln and caused the Southern states to feel their only option was secession. (Less than a week after Gen. Robert E. Lee surrendered, when the flag was raised once again over Ft. Sumter where the first shots were fired, Garrison was present — at Lincoln’s invitation — to see the fruit of his 35-year labor.)

It is a moving and emotional documentary in part because the horror of slavery is so vividly recounted, but also because it reveals and celebrates the audacity and grit of people who simply will not take “no” for an answer. Those who feel that religion is too often used as an excuse for violence and exploitation may take some comfort in the role it played in ending slavery; virtually every abolitionist, especially Grimke and Garrison, believed they were doing God’s will and that the collective soul of America would never be safe until the slaves were freed.

If true greatness is difficult to achieve for those in power, it is virtually impossible for those who are not. And yet the dedication of a small group of ordinary Americans, fighting for the rights of people they did not know, changed the world completely.

1.8.13

Deseret News, Blair Howell – ‘The Abolitionists’ shows long journey to ending slavery. While director Steven Spielberg and screenwriter Tony Kushner never intended to tell the complete story of end of slavery with “Lincoln,” the movie’s detractors will find much to admire in a new PBS documentary.

The popular movie is dedicated to the proposition that Lincoln freed the slaves. But the end of bondage did not come with the House of Representatives’ vote on the Thirteenth Amendment that he persuaded.

There were central roles played by a number of passionate 19th-century antislavery Americans in the decades leading up to the Civil War.

The three-part series “The Abolitionists,” airing Tuesdays on KUED on Jan. 8, 15 and 22 at 8 p.m., reveals the visions of the small band of idealists and the trials they endured. The journey to issuing the Emancipation Proclamation was a long and tortuous one.

Timed to coincide with the 150th anniversary of the proclamation (not intentionally with the release of “Lincoln”) on Jan. 1, 1863, “The Abolitionists” shows the complexities of what it took to end slavery and clearly demonstrates the events leading to the Civil War.

Black and white, Northerners and Southerners, poor and wealthy, the passionate anti-slavery activists “tore the nation apart in order to form a more perfect union.”

“This film helps us think about the long process that preceded the Emancipation Proclamation and about the people who put their lives on the line every day by speaking out against slavery,” says Armstrong Dunbar, one of the historians who participated in the production of the film. “It’s a very nuanced view of the way abolitionists went from being considered a fringe group to becoming a force to be reckoned with.”

“The Abolitionists” focuses on five individuals — Frederick Douglass, William Lloyd Garrison, Angelina Grimké, Harriet Beecher Stowe and John Brown — and tells their impactful, intertwined stories. The inclusion of professional filmed re-enactments is what elevates this production to be more deeply memorable above other similarly themed TV programming. The documentary opens with a segment on the deeply religious Grimké. The vocal abolitionist had no concern about renouncing her heritage as a member of a rich, plantation-owning clan in Charleston, S.C. As a daughter of privilege, Grimké saw the horrors of slavery firsthand and became one of the most outspoken foes of slavery. Yet for the purposes of a documentary, only two photographs of her have survived. Writer-director Rob Rapley cast a professional actress to portray Grimké and other family members, a technique he continued with the other four contributors to the anti-slavery movement.

“Law & Order” veteran Richard Brooks plays Douglass, who was born a slave and escaped to freedom. Douglass becoming a dazzling speaker and writer, one of the most eloquent in American history.

Theater and film actor Neal Huff plays Garrison, the publisher of the abolitionist newspaper The Liberator, one of the most influential of the antislavery newspapers throughout the north. Garrison was a founder of the American Anti-Slavery Society.

Stowe, among the country’s first celebrity authors, was another who outraged many from her writings. I am embarrassed to admit that her name is mostly remembered because her “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” is part of the storyline of the Broadway musical “The King and I.”

The abolitionists were a “tiny, tiny band of people. It really was a fringe-fringe movement,” Rapley says. “They were up against inconceivably large obstacles, economically and socially, in terms of the received wisdom of the times.”

Without the efforts of these abolitionists exerting pressure and influence on both Congress and Abraham Lincoln, the institution of slavery may have continued for many more years. How tragic it would be if their names were forgotten.

1.7.13

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Tony Norman – PBS trumps Hollywood examining slavery. Steven Spielberg’s “Lincoln” may have lost in most of its Golden Globes categories Sunday, but it is still one of the best films of 2012. Having said that, it is exposition heavy. Its attention to the minutiae involved in passing the 13th Amendment comes at the expense of portraying the brutality of slavery on a personal level.

Though slavery is acknowledged as the casus belli of the Civil War, we never see actual slaves in “Lincoln,” though White House servants make dutiful appearances. While the film opens with black soldiers fighting valiantly for their liberty in a muddy field, most of its African-Americans occupy the background like elegant furniture when they’re not filing quietly into segregated balconies to hear their fate debated by Congress.

In “Django Unchained,” director Quentin Tarantino compensates for the lack of agency by blacks in Mr. Spielberg’s film by portraying the period leading up to the Civil War as an extension of blaxploitation cinema. In Mr. Tarantino’s take, Django, a runaway slave, kills even more white people than the black soldiers managed in the opening scene of “Lincoln.” He’s an antebellum Shaft with a license to kill.

Last week, an NRA hack offered an unintentionally hilarious suggestion: If blacks had only been given access to guns after being brought to this country, slavery wouldn’t have existed. “Django Unchained” embodies this revisionist notion with bloodthirsty gusto. After all, a revenge fantasy unmoored from the tyranny of history or moral responsibility is the best kind.

For good or ill, “Lincoln” and “Django Unchained” represent Hollywood’s best thinking about the meaning of war and slavery as we observe the 150th anniversary of a conflict that turned America into a charnel house with more than 600,000 dead when it was all over in 1865.

Both films are entertaining, but you have to look elsewhere for a more robust explanation of the depths of the country’s moral dilemma. “The Abolitionists,” a three-part series on PBS this month, goes a long way in providing context about the Civil War and the decades-long battle preceding it to end slavery.

Before Lincoln saw the light, there were thousands of Americans putting their lives on the line daily to abolish slavery. “The Abolitionists” focuses on five leaders of this morally focused but often fractious movement: Frederick Douglass, William Lloyd Garrison, Angelina Grimke, Harriet Beecher Stowe and John Brown.

The first installment aired last week and explored what motivated these abolitionists whose lives intersected at key moments between the mid-1820s and 1838. We meet the young Douglass, an intellectually precocious slave who learned to read despite the laws forbidding it. Douglass’ growing literacy is inspired by Garrison’s anti-slavery crusade in the nation’s first abolitionist newspaper, The Liberator.

Tonight’s installment on WQED sheds light on the years 1838 to 1854, when Douglass, who apprenticed at Garrison’s side before their bitter estrangement, became the movement’s most powerful spokesman. After his autobiography is published, Douglass’ former master in Maryland tries to recapture him, forcing him to flee to England until supporters “buy” his freedom, making his return to America as a free man possible.

Douglass also has to navigate the ideological space between Garrison’s insistence on nonviolent religious piety and the insurrection planned by John Brown, who insists only violence can cleanse America of its original sin. Meanwhile, Harriet Beecher Stowe becomes the most influential author in America with the publication of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” a novel born out of the searing loss of her first child.

All of this takes place with the 1846 war with Mexico and the Great Compromise of 1850 in the background. Once the Fugitive Slave Act is implemented, even the most committed abolitionists begin questioning whether the nation can ever be cleansed of its original sin without a violent uprising by slaves and like-minded white people.

Next week’s installment chronicles the nation’s sojourn from John Brown’s arrest, trial and execution to Lincoln’s dithering over whether to issue the Emancipation Proclamation. We rejoice with the abolitionists over the ratification of the 13th Amendment and the renewal of friendship between Douglass and Garrison. While Lincoln is given his due, there’s no doubt that he was far from America’s MVP when it came to ending slavery.

“The Abolitionists” reminds us that slavery in America was ended by a committed movement of troublemakers, not the noblesse oblige of one man. John Brown was wrong, after all.

1.15.13

San Francisco Chronicle, Dave Wiegand – Hokey re-enactments detract from worthy ‘Abolitionists’ documentary. The sesquicentennial of the Emancipation Proclamation’s signing is one reason to look back at the uphill battle of the movement to end slavery in the United States, and Steven Spielberg’s hit film Lincoln is another. But the movement’s significance to our history alone makes it a worthy subject for the three-part American Experience documentary launching Tuesday on PBS.

The Abolitionists, written and directed by Rob Rapley, is a barely adequate documentary blending archival images with minimally convincing re-enactments. Fortunately, the content outweighs the weakness of the filmmaking.

Rapley’s film focuses on several key members of the abolitionist movement, including author Harriet Beecher Stowe, radical activist John Brown, former slave Frederick Douglass, South Carolina belle Angelina Grimk, who broke with her slave-owning family, and William Lloyd Garrison, who created the anti-slavery newspaper The Liberator as a platform for his deeply held views.

From the first days of the new republic, slavery was a complicated and complicating practice. By 1820, there were some 2 million slaves in the United States and slavery itself was known as “the peculiar institution.” As the abolition movement grew as a human rights battle, it became not just about slavery, but about race as well. And no matter how many people were drawn into the movement’s ranks, it ran up against an even more powerful cultural opponent—economics—and not just in the South, but in the North as well.

The abolitionist movement was both organized, through the American Anti-Slavery Society, and unrelenting. Yet its leaders often disagreed on the best method to rid the nation of slavery. Garrison advocated peace and persuasion. Brown, the leader of the raid on Harper’s Ferry, believed it could only be achieved through bloodshed.

Setbacks including the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law and the Supreme Court’s decision in the Dred Scott Case that Congress could not outlaw slavery radicalized even Garrison. He came to believe the entire nation needed to start over, that the first republic, as it was known, had to die to create that “more perfect union” as cited in the preamble to the U.S. Constitution.

Rapley’s film does a decent job of slicing through the mythology of the abolitionist movement to show how much its leaders both worked together and disagreed while still keeping a collective eye on the prize. It also disabuses us of the notion that Lincoln was the great white hope of the abolitionist movement from the get-go. That isn’t to say he shouldn’t be viewed as a hero, only that, like much of the nation, his views on slavery had to evolve.

Rapley’s film is watchable and informative, but the re-enactments come up short. He’s employed experienced actors to play Garrison, Brown and the others, but because scenes rarely feel very believable, they don’t contribute as much as the archival photographs and other historical images. Of the actors, only Richard Brooks ( Law & Order, Firefly) as Douglass manages to overcome the phoniness of the settings.

The film also includes a good deal of commentary from modern-day historians, but their contributions often seem merely to repeat the information provided in Oliver Platt’s narration. What’s largely missing from the commentary, especially given the fact that it’s a three-hour documentary, is how the abolitionist movement may have impacted our nation beyond the Civil War. Slavery may have been eradicated, but the debate about race continues, and its roots can be found in the abolitionist movement.

DVD Verdict – As Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln arrived in theatres and offered a celebratory portrait of the man who signed the Emancipation Proclamation, PBS offered a three-part documentary series detailing the lives of the individuals who did much of the work to make that moment possible: The Abolitionists. By zooming in on the lives of five key members of the Abolition movement, the series offers a satisfying and moving examination of the individuals who boldly took the unpopular view that slavery was an abomination during a time in which the American south depended on slavery and in which the American north was content to look the other way.

The series is presented in a somewhat unusual way, offering a combination of staged drama and traditional documentary material. There are only so many photos and letters available related to the subject, so The Abolitionists spends a good deal of time presenting historical re-enactments—sometimes they’re silently emoting as narrator Oliver Platt (an unusual choice, but he’s quite good as this sort of thing) talks about them, and sometimes they’re participating in scripted scenes. There are moments in which the approach seems a little hokey, but generally these scenes stand a notch or two above the sort of footage The History Channel so frequently delivers.

The five individuals featured are Frederick Douglass (Richard Brooks), Angelina Grimke (Jeanine Serralles), John Brown (T. Ryder Smith), Harriet Beecher Stowe (Kate Lyn Sheil) and William Lloyd Garrison (Neal Huf). Through these individuals, the filmmakers are able to capture a wide variety of angles on the subject: the pacifists, the feminists, the African-Americans, the aggressive militants and so on. While acknowledging that all of these individuals played a large role in the effort to free slaves, the documentary also demonstrates that their methods varied wildly and sometimes led these people into sharp conflict with one another.

Three hours may sound like a lengthy running time, but it positively flies by thanks to the absorbing construction of the documentary (which jumps back and forth between its central characters as it moves forward chronologically) and the compelling subject matter. Granted, there may be some out there who will find lengthy examinations of the philosophical differences between William Lloyd Garrison and John Brown less fascinating than I do, but the documentary really is a simultaneously accessible and deep look at a subject that often doesn’t get the attention it deserves.

The series even manages to bring some tension into the proceedings despite the fact that we’re full aware of the final outcome. Sure, we know that slavery will eventually be outlawed, but how many of us know whether Douglass and Garrison will ever speak to each other again after a nasty split? Over time, many abolitionists become divided over whether to protest peacefully or take violent action against slave owners. By the time the civil war arrives, the documentary has effectively demonstrated why it seemed like an inevitability to those who had spent decades fighting for the end of slavery.

Another intriguing aspect is what a crucial role religion plays in this saga. Nearly every major participant in this tale is fueled by some sense of religious conviction. Brown’s murderous rampages, Stowe’s novel, Douglass’ speeches…they’re all fueled by the conviction that this is what God wants them to be doing (never mind that most of the churches were in disagreement with them at the time). Divinely inspired or not, it seems that nearly every friend or foe of slavery felt strongly that they were on the side of righteousness. Regardless of what your own religious beliefs may be, it’s refreshing to see the documentary emphasize just what a large role it once played (for good or ill—there’s plenty of both) in American society.

The DVD transfer is strong, allowing the viewer to appreciate the impressive amount of work put into the re-enactments the film offers. These scenes naturally have a more cinematic quality, while the talking head sequences have the standard digital documentary look. The Dolby 2.0 Stereo track gets the job done nicely, though this is a dialogue-driven affair that doesn’t offer much in the way of complex sound design. No supplements are included.

The Abolitionists is a strong, detailed examination of one of the most important movements in American history. Highly recommended.

stagehappenings.com, Dale Reynolds – What an extraordinary three-hour documentary this is, originally shown on PBS’ American Experience in 1987, about the rise/fall/rise of the anti-slavery moment, Americans who called themselves “Abolitionists” i.e., common-folk who sought to abolish the reality and legality of white-on-black slavery.

Although slavery itself – one person owning the life of another – is as old as humankind, by the late-18th to mid-19th Centuries, it had begun to be viewed as a moral wrong: owning another was against God’s Will, as the philosophers of the Age of Enlightenment began to believe. But trying to convince prosperous white slavers (plantation owners or sea-captains and their immediate kin) that the practice was evil and those who practiced it were open to an afterlife of damnation was an uphill march. Beginning around 1775, when Alexander Hamilton co-founded the first Manumission Society in New York City, up until the end of the destructive Civil War (1861-65), the Abolitionist Movement made steady headway, then lost it in the conservative backlash in the 1850s, until finally the 13th-16th Amendments to the U.S. Constitution, during and after the Civil War, settled the issue of slavery – if not racial discrimination – forever.

As writer/director/producer Rob Rapley tells it, the heart of the movement were a half-dozen courageous men and women, among them escaped slave Frederick Douglass, publisher William Lloyd Garrison, Quaker Angela Grimké, author Harriet Beecher Stowe, and radical farmer John Brown (all European-American).

Rapley’s three hours examines in great detail, using both period photos, drawings and engravings as well as actor-reenactments, to vividly tell the stories that make up a morally-depraved part of America’s past. Using period settings that still exist, accurate costuming and actors who look remarkably like the characters they are playing, he makes very clear what happened to our heroes, and the toll it took on them.

Frederick Douglass went on to have a full-career as orator, author, minister-resident /counsel-general to the Republic of Haiti, by appointment of President Grover Cleveland; Garrison was nearly lynched for his anti- slavery editorials; Mrs. Stowe was greeted by Abraham Lincoln who said of her: “Here’s the little lady who caused the Civil War”; and John Brown was publically hanged for his abortive attack on a Federal fort in Virginia, making him a true martyr for the cause.

Actors Richard Brooks as Douglass, Neal Huff as Garrison, Jeanine Serralles as Grimké, Kate Lyn Sheil as Stowe and T. Ryder Smith as Brown aren’t given much screen time but do make their characters very much alive and off the printed page.

History-buffs will relish this splendid documentary, which covers a great deal of intimate information, filling in our knowledge and making us more aware of what happens when freedoms are casually and deliberately removed, such as the current attacks on a woman’s right to choose abortion as an option to birth. Knowing the past can teach us what we need to know about protections in the present.

HistoryNet.com, Gerald D. Swick – Thirty years after the former 13 American colonies abandoned the Articles of Confederation “in order to form a more perfect Union” and “secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity,” slavery still existed within the United States. Its eventual demise was assumed to be not far beyond the horizon; every Northern state had abolished slavery, and Congress had prohibited it in the Northwest Territories. But the development of the cotton gin made possible more efficient methods of processing cotton fiber. Increased demand for cotton required ever-greater growing areas, necessitating increased use of slave labor in the South; Northern textile mills also depended upon those Southern slaves to keep cotton fibers flowing northward. By 1830, slaves represented the largest financial asset in American society—more than all the manufacturing and transportation industries put together. Only the land itself surpassed the combined worth of slave property.

Those observations come early in The Abolitionists, a new, three-part series from American Experience on PBS, directed by Rob Rapley (Freedom Riders, The Supreme Court, Wyatt Earp). The first installment of The Abolitionists airs Tuesday, January 8, from 9:00 to 10:00 pm ET. The second and third parts follow on January 15 and 22. As always, check your local PBS listings for times in your area.

The series explores the lives of five of the most prominent voices of the abolition movement, but more importantly it examines the rise, fracturing, decline, and resurgence of what was arguably the most important social crusade in all of American history. It tells its story in a compelling manner—this reviewer watched all three episodes back to back and was never bored—and leaves viewers with a deeper understanding of the conflicting approaches to ending slavery in America.

The format is well-trod ground: narration while old photos and documents fade in and out; dramatic re-enactments of some key events; commentary from a few historians. This recipe has proven successful many times, and it works particularly well in this series. The “talking head” sequences are well-spaced throughout instead of dominating the production, and what makes The Abolitionists so watchable is the acting by those portraying historic figures, including Angelina Grimke (played by Jeanine Serralles), Frederick Douglass (Richard Brooks), William Lloyd Garrison (Neal Huff), John Brown (T. Ryder Smith), and Harriet Beecher Stowe (Kate Lyn Sheil).

The five represent a disparate group. Grimke was born into a slave-owning family of the South Carolina aristocracy, but she leaves the South because of her opposition to slavery. Douglass was a slave who escaped to freedom and became an inspiring figure for both white abolitionists and blacks who hoped to find freedom and / or rise in society. Garrison found his spiritual fulfillment as publisher of the most prominent abolition newspaper, The Liberator. Unlike Garrison, who staunchly advocated non-violent evangelism as the means of ending slavery (lead slave owners to redemption by getting them to renounce the peculiar institution), John Brown became the face of violent opposition to slavery, a saintly martyr to abolitionists but the devil incarnate to slave owners and others who opposed the “fanaticism” of abolition. It was Harriet Beecher Stowe, however, who discovered the way to swell the ranks of abolitionists was not through logical appeals nor violence but by touching their heartstrings, as she did with Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

Viewers whose knowledge of the abolition movement is limited to the surface material they learned in school will likely be surprised by some of the information presented in this series. Northern mobs threatened Garrison’s life, and in Philadelphia, the City of Brotherly Love, a mob set fire to a prominent building the night after Angelina Grimke spoke within it. White firemen stood by, watching it burn.

While Uncle Tom’s Cabin is well known, many Americans are unfamiliar with Slavery As It Is, a powerful compilation of slave abuse taken from the words of slave owners themselves (“I burnt her with a hot iron.”) published by Grimke and her husband. Perhaps the information that will most surprise viewers is that within the space of five months President Abraham Lincoln declared the Civil War was not about slavery; he suggested all blacks should leave the U.S., because he despaired of them ever having equality here; proposed the Emancipation Proclamation freeing all slaves in rebel territory; and offered a peace plan to Congress that would have guaranteed Southerners they could retain their slaves until 1900 if they would lay down their arms.

The confusing signals coming from the president led Garrison to deplore Lincoln’s association with “the white trash of Kentucky,” which had left him with “nothing noble or uplifting in his character.” Douglass went even further, declaring Lincoln was “a genuine representative of American prejudice and Negro hatred.” Rather curiously, the program never mentions that, as a legislator in Illinois, Lincoln voted with the majority to condemn the agitation of abolition societies, then promptly offered a bill mollifying the language of the previous bill.

There is also not much by way of explaining why slavery was so ingrained in America, especially in the South, beyond the economic considerations. The focus of the program admittedly is the abolitionists, but spending a little more time discussing the political considerations, religious and social beliefs that underpinned the peculiar institution would have enhanced viewers’ understanding of why so many Americans, South and North, opposed abolition so intensely.

Apart from those points, The Abolitionists succeeds in telling the story of the abolition movement and the gradual shifts in public opinion that ultimately allowed abolitionists to achieve their goal of freedom for all Americans. Highly recommended.

Worldwide Socialist Website, Tom Mackaman – PBS’s The Abolitionists: Remembering the political struggle against slavery. The Abolitionists, which aired in three parts in January on the Public Broadcasting System (PBS), is a reminder that the fight against slavery in the US was a long and bitter political struggle. The film can be viewed for free on the PBS web site.

“Abolitionist” was the name given to those who sought the total elimination of slavery from the United States in the period before the Civil War. They constituted a small and persecuted minority at first, but their principled opposition to slavery and their relentless exposure of the “Slave Power” that dominated the federal government won growing numbers of adherents as tensions between North and South mounted. The abolitionists’ own actions came to play a powerful role in the developing sectional crisis. Abolitionist books, pamphlets, public meetings, and assistance to runaway slaves brought vitriolic and violent responses from the Southern planter elite and their political allies in the North.

The victory of the North in the Civil War (1861-1865) vindicated the abolitionists. The war to preserve the Union could not be won without ending slavery. Once Abraham Lincoln and the Republican Party, driven by the logic of war, moved to this position, the abolitionists’ aim was realized: Slavery, and with it the Southern plantation elite, was destroyed.

The PBS documentary The Abolitionists follows this process through the lives of five leading figures of the movement: Angelina Grimké, agitator and author; William Lloyd Garrison, founder and editor of the leading abolitionist newspaper, The Liberator; Frederick Douglass, the foremost free black opponent of slavery; Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of the anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom ’ s Cabin; and John Brown, who took up arms against slavery in Kansas and later in an unsuccessful attack on the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia.

Grimké (played by Jeanine Serralles) came from one of the elite Charleston, South Carolina, slaveholding families, and in this sense her embrace of abolitionism, together with her elder sister, Sarah Grimké, was an act of class betrayal. Grimké made contact with Garrison, who without permission published her letter condemning slavery in The Liberator. This event turned Grimké into one of the foremost abolitionists and set the stage for her anti-slavery polemic, An Appeal to the Christian Women of the South, which circulated widely in the late 1830s.

Harriet Beecher Stowe (played by Kate Lyn Sheil) was born to a different sort of elite family. Her father, Lyman Beecher, was one of the leading evangelists of the “Second Great Awakening.” Then living in Cincinnati, Stowe was deeply impacted by slavery when she crossed the Ohio River into Kentucky as a young woman, and there witnessed the separation by sale of a slave mother from her child. As the documentary presents her evolution, the loss of a favorite child to an epidemic brings Stowe to sympathize with slave mothers. The outcome was the publication of the powerful novel (and play) Uncle Tom ’ s Cabin, which sold millions of copies in the 1850s, saturating the population in the North with anti-slavery ideas.

John Brown (T. Ryder Smith), a tanner and sheep trader who had lived variously in Pennsylvania, New York, Ohio, and Massachusetts, was radicalized by the lynching of abolitionist publisher Elijah Lovejoy in Illinois in 1837. Brown, the documentary recounts, stood up at a prayer service where Lovejoy’s killing was being condemned and announced, “Here, before God, in the presence of these witnesses, from this time, I consecrate my life to the destruction of slavery.” In the 1850s, Brown led anti-slavery militants against pro-slavery forces in “Bleeding Kansas,” and in 1859 with a small band of followers he led a raid on the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry. His dream of triggering a slave rebellion that would sweep the South failed, but his audacious act considerably heightened the sectional crisis, which would explode into civil war after Lincoln’s victory in the 1860 election.

Brown had attempted to win to his cause Frederick Douglass, who by the 1850s had already established a national and international reputation, both for his oratory and because of his autobiographical account of slavery and his escape, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. The portrayal of Douglass by actor Richard Brooks, best known for his performance as District Attorney Paul Robinette in the television program Law and Order, is the strongest in the film. This must be in part attributable to the power and directness of Douglass’s writing and speaking, from which the film quotes directly.

To the extent that the documentary intertwines these historical figures together, it is through William Lloyd Garrison (played well by Neal Huff), whose founding of The Liberator in 1831 must be considered the beginning of the abolitionism as a coherent national movement. “There shall be no neutrals; men shall either like or dislike me,” Garrison writes in the first issue. “Let Southern oppressors tremble, let their Northern apologists tremble —let all the enemies of the persecuted blacks tremble. On the subject of slavery, I do not wish to write with moderation. I am in earnest—I will not equivocate—I will not excuse—I will not retreat a single inch—and I WILL BE HEARD.”

Garrison recruited both Douglass and Grimké, and his newspaper had a powerful impact on Stowe and Brown in quite different ways. Stowe’s own literary efforts were made possible by The Liberator, while Brown came to reject Garrison’s peaceful tactics.

The documentary’s biographical dramatizations are little more than character sketches, which is perhaps the most that can be expected from a three-hour documentary. Much must be left out. Grimké’s remarkable family, outside of her sister, is presented as an obstacle to her development. Lost is the fact that her father had been a veteran of the Revolutionary War and evidently held anti-slavery views—not uncommon among slaveholding planters of the revolutionary generation. A brother was a notable jurist and legislator who opposed his own state of South Carolina in the nullification crisis of 1832. It was a remarkably political family.

Similarly, the documentary stresses Stowe’s loss of a favorite child as the primary impetus in her move toward outspoken abolitionism. This may have been a tipping point for Stowe, but it was very common for nineteenth century mothers to lose children—few were the families in which such an event did not occur. Clearly much more went into Stowe’s determined stance. It is notable that her brother, Henry Ward Beecher, was also an outspoken abolitionist. Though not an abolitionist, her father, Lyman Beecher, held anti-slavery views, and when students at the Cincinnati college where he was president, Lane Theological Seminary, condemned slavery, the college was attacked by pro-slavery mobs in 1834.

The documentary does little to analyze the intellectual and political currents that fed into the abolitionist movement, and so the emphasis falls on the abolitionists’ indubitable moral courage. We see the religiosity of several of the characters—least in Douglass and most in Grimké. But that this is a particular kind of religiosity in a particular place and time, and a religiosity moreover oriented to the question of slavery, is a historical question that is present but underdeveloped. After all, as Lincoln wryly noted in his Second Inaugural, both sides in the Civil War “read the same Bible and pray to the same God, and each invokes His aid against the other.”

The documentary stresses Garrison’s attack on the Constitution as the bulwark of slavery in the US. Unfortunately, this is implicitly equated with an attack on the American Revolution. “[T]he Republic itself had been corrupted at birth, its original sin implanted in a founding document written largely by slaveholders,” the narration goes.

As historian Alexander Tsesis has recently shown, the abolitionists’ attack on the Constitution and its guarantees of slavery was coupled with their celebration of the Declaration of Independence as the real creation of the republic—it is not by accident that the founding document of the anti-slavery movement drew in its title inspiration from the Declaration of Independence, taking for itself the name Declaration of Sentiments. The documentary makes no mention of the Declaration of Independence.

The historians interviewed do not add as much depth as one might have hoped. One partial exception is David Blight who early in the documentary helps viewers comprehend the power of the slave system: “Slaves were the single largest financial asset in the entire American economy, worth more than all manufacturing, all railroad, steamship lines, and other transportation systems, put together.” Later, Blight notes the importance of the Mexican-American War (1846-1848) in deepening the sectional crisis: “The Mexican War unshucked slavery. It just took it out of its shell. All those efforts to contain this issue couldn’t work anymore.”

Identity politics rears its empty head in commentary from literature professor Lois Brown, who obfuscates a rift that developed between Douglass and Garrison. “On the one level, you hate to reduce it to race. On the other, it’s a reality,” she intones. “No matter how many stories Garrison hears, no matter how many coffles he sees, no matter how many mothers he can imagine and conjure up, Douglass has had that experience. Garrison is a white man in a white man’s America.”

This commentary implies that the dispute was over Garrison’s allegedly conservative tactics, a conservatism that arose from Garrison’s skin color, as Brown would have it. In large measure, instead, the rupture emerged over Garrison’s rejection of the US Constitution, which Douglass continued to believe could be invoked in the fight against slavery—on this issue, it was Douglass who held the more conservative stance. In any case, Garrison had a great many black followers, and Douglass a great many white followers. Neither viewed their separation through the racial prism that Brown implants.

These criticisms aside, The Abolitionists makes accessible the story of the struggle against slavery in America and deserves a broad audience.

The documentary captures the powerful moment that came near the end of the Civil War when Lincoln invited Garrison to visit Charleston, the cradle of secession, recently captured by the Union army. The two men have become allies. “Either he’s become a Garrisonian abolitionist,” Garrison said of Lincoln, “or I have become a Lincoln emancipationist, for we blend together, like kindred drops, into one.”

“For his part,” the narration notes, “a few days earlier Lincoln had told an admirer that he had been ‘only an instrument’ in the anti-slavery struggle. As he put it, ‘the logic and moral power of Garrison and the anti-slavery people’ had done it all.”

In Charleston, Garrison was greeted by thousands of freed slaves. “For almost four decades, Garrison had dedicated his life to this moment. He had created a movement, had led it through every adversity without wavering. The Liberator had become not only the most influential voice of abolition, but the symbol of its tenacity. One thousand eight hundred and three issues, every one set by hand, most by Garrison’s own. And this, Garrison felt, was a fitting occasion to print the last.”

The documentary concludes with Douglass’s eulogy of Garrison in 1879: “Now, the brightest and steadiest of all the shining hosts of our moral sky has silently and peacefully descended below the distant horizon. He moved not with the tide, but against it. He rose not by the power of the Church or the State, but in bold, inflexible and defiant opposition to the mighty power of both. It was the glory of this man that he could stand alone with the truth, and calmly await the result. Now that this man has filled up the measure of his years, now that the leaf has fallen to the ground as all leaves must fall, let us guard his memory, let us try to imitate his virtues, and endeavor as he did to leave the world freer, nobler, and better than we found it.”