Some notes

People sometimes ask me what it was like to work on Brainscan. Short answer: I loved it. Here are a few notes and stories.

I auditioned for the film with sides from what seemed to be an early version of the script, when the Trickster might have been mostly an off-screen voice, or an animated face on the computer. It was hard to tell since we were not given anything but individual scenes. In any case the language for the Trickster in those audition sides was ornate, even pseudo-classical, and so I was amused to walk into the audition and see several actors I had worked with doing Shakespeare plays.

I’d gotten the title of the film wrong, and told the receptionist I was there to audition for “Brainstem”. She smiled politely.

The initial audition was done on tape in NYC, and then sent to LA for review, which took so long I figured nothing had come of it. I was surprised to hear a few weeks later that the creative team wanted to see me at a callback. Director John Flynn and co-producer Jeffrey Sudzin came to NY for that second audition and spent most of it looking not at me standing right there in front of them in the room, as I was used to at theatre auditions, but at a small video monitor next to them on the table. I didn’t realize it was a close-up of me they were watching, and I remember thinking that I must be doing pretty badly, they weren’t even paying attention. Then they started talking to each other and pointing something out on the screen, and I felt deflated: now they were even talking during the audition! I left feeling disheartened, but later learned that was a “very LA” style of audition, (perhaps based in part on the fact that directors need to see how the camera, and not the human eye, is reading the performance). Anyway, a friend told me it meant I had done well, but I wasn’t so sure. I didn’t know at the time that the team was in the process of expanding the character into a 3-dimensional being, and that part of the discussion during the audition was about how much makeup might be needed. At that point I still thought it was going to be pretty much just an off-screen voice.

My agent called a few days later and said they were interested in me for the part, but wanted to know if I would be willing to be seen “on camera a little”? I said “Sure”, and they called again a few minutes later and said “Um, on-camera wearing a prosthetic chin. Or something.” I said yeah, that was fine, and had no idea what I was in for when they called a third time and asked: “So: are you allergic to make-up . . . ?”

The crew at Steve Johnson’s X/F/X studios in LA, where the makeup was designed and tested, were a wild and creative bunch, and I had a great time letting them play with building “The Trickster” on me. The studio itself was a Fangoria fever-dream, the walls lined with plaster casts of dozens of actors from horror and sci-fi films and the masks they had worn, with all kinds of cinematic beasts and monsters hanging from the ceiling or on display in large glass cases. (I recall in particular the ethereal deep sea creature from the film The Abyss). And everywhere were humming machines and makeup artists at their spattered, cluttered work stations, creating bizarre creatures or diseased limbs or bubbling eyeballs. One guy was calmly working on recreating in latex something from what they called The Wound Bible, crime-scene polaroids of actual carnage. The alley outside the studio was lined with dead-body dummies hung from racks like clothes at a dry-cleaners, all in various stages of decomposition, for a zombie film. “This must be the place”, the cab-driver said, dropping me off.

The first thing they did was make a plaster cast of my head. They sit you down in a large antique barber’s chair, shirtless, and put a garbage bag over you like a poncho, your head sticking out through a hole cut in the bottom. Your face is coated with vaseline, your ears plugged and then drinking straws are inserted up into your nose so you can breath. Then your face is covered with a smooth white paste, put on by the fistful, from a bucket. The paste is cool, and covers your skull. You don’t hear much after this point. The gel is then covered with strips of plaster, which are very hot, so a pleasant warmth penetrates the cool gel, which then gets weirdly hot as it starts to set. Your head is getting heavy by this time, as they wrap many layers of the plaster-coated gauze around you. You can hear them shouting instructions and encouragement to you from what sounds like far away. One of the things they’re saying is that it’s important you don’t change expression, or move your face much. The plaster continues to get tighter as it dries. All you can hear at that point is your own breathing in and out of the straws. It’s a pretty helpless feeling, sitting there in a garbage bag with your head the size and weight of a bowling ball, the drying plaster clamping tighter onto your face. A long time goes by. Someone taps your shoulder and bellows: “We are going to GET YOU OUT now! DO NOT MOVE!” and you hear – far off through your cocoon of cement – a circular saw start up. They cut the plaster cast off from ear to ear, going over the top of the head – you hope they don’t slip – and down the other side. Then several pairs of hands brace you from all sides, and someone shouts: “We’re pulling off the back half! Push forward!” The heavy plaster pulls free and it feels like the back of your skull is coming off with it. Then they shout: “WE’RE GOING TO PULL IT OFF YOUR FACE. BLOW OUT. BLOW OUT HARD.” The dozen hands push or pull at you again and the skin of your face stretches out as the mask is removed; your expelled breath and the gummy plaster pulling free combining to make a sound like 5 bathtubs draining at once. Cold air rushes onto you, your skin and eyelids and lips slap back onto your skull, and all the make-up guys crowd to look into the mask, to see if it is a useable impression. “Good one!” they announced and slapped me on the back.

We actually did a 2nd mask that day, trying to see if I could hold an intense “Tricksteresque” facial expression until the plaster dried. They wanted to try it but didn’t think it was possible – and they were right – you just can’t freeze facial muscles for that long. (Try it sometime when you’re bored.)

The alternate coolness and heat of the gel and plaster, the heavy head and muffled silence, and especially that giant sucking sound as the mask comes off, with your whole face stretching out for what seems a half a foot and snapping back into place is something they should offer as therapy – it’s weirdly relaxing.

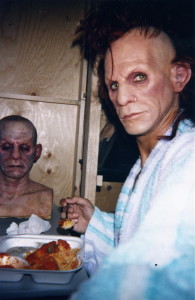

My discarded plaster self, with zombies.

The Trickster would have some sort of weird eyes, they said, so we tried various contacts. The first set were the old variety, like Lon Chaney old: hard, and covering half the eyeball, they had to be inserted under the eyelids, top and bottom. That took a while. Unfortunately. They looked good, though – a deep, glassy red – but were painful to wear and could only be kept in for short periods. The sound and feel of those coming out was not fun. They tried a series of soft lenses after that, like normal contacts, and liked a pair that had a sort of leopard-pattern to them. But for one reason or another, those wouldn’t work and they went with just a shade of yellow.

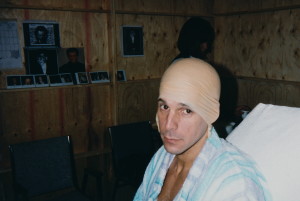

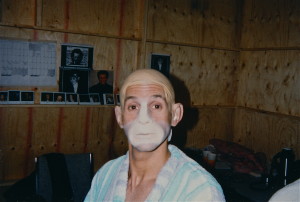

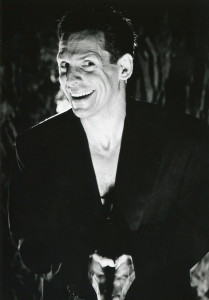

They tried a few looks for the character. Here is an early version of the makeup:

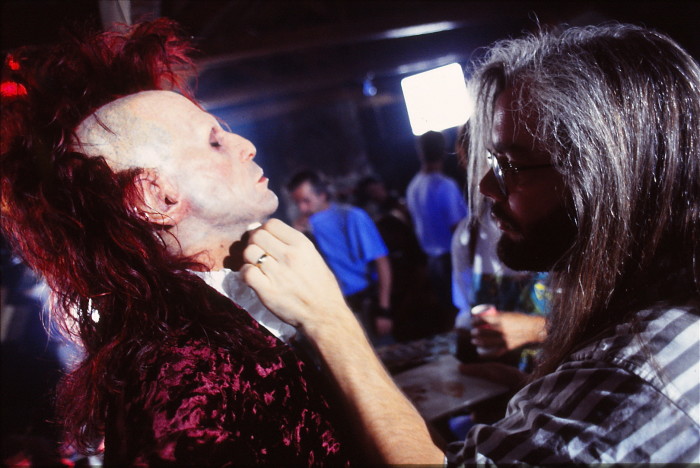

Andy Shoenberg was the X/F/X artist with me on the shoot, and we had a great time. He was a serene and generous guy, and excellent at what he did. An artist and gentleman.

The wonderfully-named Eva Coudouloux assisted him on the shoot, which was done in Montreal. Eva was a Parisian relocated to Canada, and had a wicked wit which nicely complemented Andy’s Buddha-calm. (I once asked her, “How do you say ‘I am happy to see you again’ in French?” She thought for a moment, and said “In France, we are never happy to see anyone again.”)

Here was the process with the makeup: I would be picked up for the day’s shoot around 4 a.m. and we were ready to start in our little room in the dark and silent studio by 5. The makeup consisted of 8 pieces, overlapping and covering the entire head. The seams were then sealed and Andy painted and stippled and dabbed, applying all the details of the face.

Then the yellow contact lenses were put in, the wig put on and the teeth inserted. The whole process took around 5 hours. There were also straps glued to my cheeks to distend my mouth, which were pulled tight and velcroed in place beneath the wig at the base of the skull. And of course there were the gloves with the prosthetic fingers. I would be in the makeup all day, sometimes for about 12 hours. It got hot in there.

You forget you have the makeup on after a while and I would often startle people inadvertently. I’d approach someone to ask a question, and they’d turn to answer and gasp when they saw me. I got used to folks saying: “Sorry! I didn’t know it was you.”

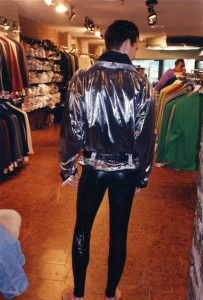

I never realized how odd I looked, even doing simple things.

Some of the crew had no idea what I looked like out of makeup. I visited the set one day when I wasn’t shooting and few of them knew who I was until they heard me speak. “That’s you?!” one of them said, disbelieving. I hope she wasn’t too disappointed.

Removing the makeup was it’s own adventure. The medical adhesive which held the pieces in place was a little too good at it’s job, and tended to get inextricably caught on things like eyebrows, eyelashes, lips, etc. Andy and Eva made it all as painless as it could be, however, and grew used to my gasps and groans as they delicately swabbed solvents at the sticky parts and pulled the mask off centimeter by centimeter. I lost some of my eyebrows and quite a few of my eyelashes during the process. It even pulled out nose-hairs, yow. Removal took about 90 minutes.

We tried many options for the costume, a few of which can be seen below. They were going for a sort of military/bondage theme, apparently. Director John Flynn eventually sketched out a look and the designers went to work on it. “Think rock and roll, not S/M!”, he said.

A wonderful old-school tailor in Montreal made all the final pieces. He came to the set for an alteration once and saw me suddenly in full makeup. Didn’t bat an eye.

I had a lot of respect for director John Flynn, the director of superb – and sorely underrated – films like The Outfit and Rolling Thunder, and a man who had served a long apprenticeship in Hollywood in the 60’s, working as assistant on films like The Great Escape. I admired how he was always trying to find ways to achieve Brainscan‘s effects atmospherically, via mood and implication, and do justice to the material without either over-burdening or condescending to it. He talked about Val Lewton, particularly Cat People, and how deftly he had been able to create a sense of dread with just shadows and sound and editing. I don’t think John wanted to use any special effects at all. He won about half those battles.

I also appreciated how kind John was to me, knowing this was my first time acting in a film, and in such an odd role. He showed me around Hollywood when I first arrived, and once we started shooting invited me to the rushes – screenings of the previous day’s footage – and had me sit next to him, quietly pointing out what worked best in the various takes. We talked a lot about how the character should be played, and how to try to balance his cartoonish and more threatening aspects. On the first day of the shoot, I’d demonstrated to John 3 different choices I’d come up with for one bit (the dance in the bedroom), and he laughed and said “Mostly 2, with a little bit of 3”. After that we always did the first take of any scene big, the second take small, and the third take with me doing “whatever you want, T”, John said. We figured that should give the editor some choices.

Producer Michel Roy was also very generous to me, and we had some great talks about how the Trickster should come across. He wanted him to be both comic and scary, and encouraged me play around with the character, and not be shy to suggest business or blocking, if I thought something might work. Any filmscript is reworked and sometimes rewritten over the course of the shoot, as the film takes shape. The scene with Trickster eating on the bed, or filming Michael with his own videocamera, for instance, were some of the moments Michel particularly let me play with. And I wound up inadvertently writing the dialogue in that video camera scene. Given how the previous scenes had been shot, Michel was talking about how the film needed the camera scene to be faster and more to the point. “Maybe something like this?” I said, and scribbled down some sharp exchanges. Michel read it and walked off with the page. He came back a little later and said he had faxed it to the folks at Sony, and showed me the reply. “Good work, T!”, it said. “But I wasn’t trying to – ” I said, embarrassed, and Michel just nodded. We shot the scene later that day. I hope it works okay.

“Yes, Master.”

Here’s something I don’t think anyone ever knew: I’m the voice of Igor, the animated phone-answering character. We were recording some of the Trickster’s voiceover dialogue in NY and at the end of the session Michel sighed heavily and started dialing someone on the phone. I asked him what was up and he said he was still trying to find an actor to record “Igor”. I said I would do it. He looked at me, considering it, phone still in hand. “We’re right here”, I said. “But, there is a contract . . . Negotiations . . . “, he said. “You’ve already paid me for the day”, I said. “Let’s try it. It’ll be fun.” So he hung up the phone and I went back into the booth. We recorded Igor speaking in the voice of Boris Karloff, Bela Lugosi, and Peter Lorre. He went with the Karloff. We never told anyone I did the voice, and it wasn’t listed in the credits. I laugh every time I hear it.

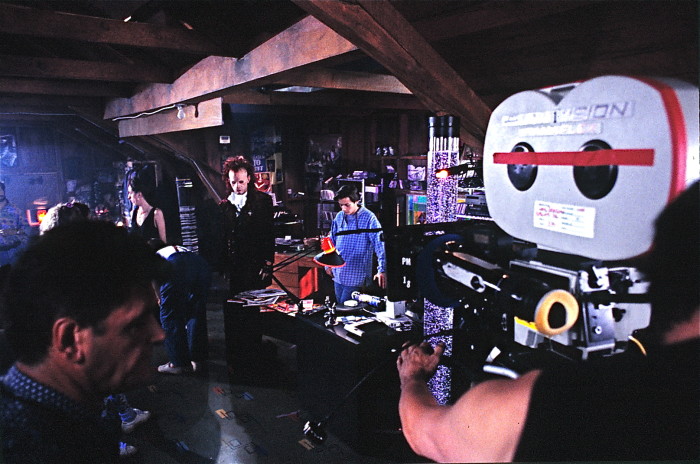

Paolo Ridolfi was the Art Designer on the film and she did a smash-up job. Always working, adding details. She was a talented abstract painter, too, when not working in film.

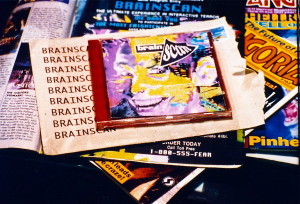

It was fun to pose for the Brainscan disc cover. We did it my first night in Montreal, at the location where they were shooting a neighborhood scene, and used the spill of light from one of the giant arclights. The crew walked around us, thinking: what is wrong with that guy?

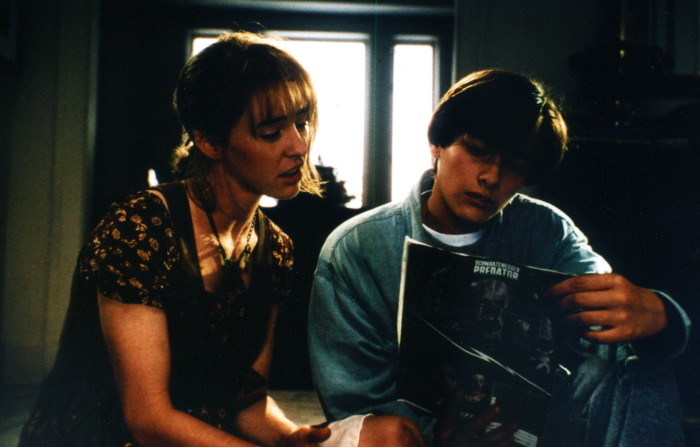

I liked Eddie Furlong and enjoyed working with him. He was a shy and genuine guy, trying to navigate the pressures of early fame as well as some difficult personal situations. It wasn’t easy, and he did it with a lot of dignity. He was serious about the work in the film, too, always trying to get it better each take.

We wound up shooting the film pretty much in sequence, which is rare, and which allowed the relationship between characters to develop naturally. For example, the first time Michael sees the Trickster is the first time Eddie saw me in makeup. The whole team kept me hidden from Eddie until our first encounter, where the Trickster approaches Michael after emerging from the TV set. So the shot in the film really is Eddie seeing me in full make-up and costume for the first time. They snuck me onto the set and I stood beside the camera, my back to Eddie, bent forward. They then called “Action!” and I straightened up and turned to face him. He laughed when they called “Cut!”, and came over to get a closer look. I’m pretty sure the reaction shot they used in the movie is Take 1 of that day.

Eddie loved the horror-makeup and was really happy when he got to wear some later in the film. He kept asking to do another take of those scenes because he didn’t want to take the makeup off.

I only had one brief scene with Frank Langella, but he was and is an elegant and imposing man and artist. He sympathized with the enveloping nature of the makeup, and told me about playing “Skeletor” in Masters of the Universe. Amy Hargreaves was very nice, a graceful and mature person and artist, even at that young age.

The special effects sequences were done in LA, but the bulk of the film was shot in Montreal. I have very fond memories of the kindness and grace of the crew and staff of the film, and of that beautiful city.

I had a great time making Brainscan, and am always happy to see it pop up occasionally on TV or at a revival cinema. I think John did achieve something of a true Val Lewton-like dread. When people talk about the film sometimes, they mention the mood of it, the tone of it. I always think: Good job, John!

I am also always happy to see some of the reactions from fans of the film. I’m glad people enjoy it. The Horror Club lives!

I was lucky to be involved in Brainscan.

Publicity

Reviews

The original reviews appear below, but there are many sites which have discussed or reviewed the film since it’s release. The views expressed are varied, to say the least – some like it, some loath it, some praise it, some mock it. It’s all cool with me.

New York Times – Janet Maslin: So True About Those Idle Hands – Brainscan makes a case for the long, hearty camping trip as it tells what happens to 16-year-old Michael (Edward Furlong), a boy who clearly spends too much time indoors. The decor of Michael’s room involves a toy noose hanging from the ceiling, horror and heavy-metal artifacts, abundant audio, video and computer equipment and a special chair in which Michael can sit when he feels like having his senses blasted by any of the above.

The film is about what happens when Michael tries out “the ultimate experience in interactive terror,” and tests the limits of technohorror as a spectator sport. Goaded by an equally horror-crazed friend (Jamie Marsh), he decides to try the video game of the title. And he expects nothing life-altering when the Brainscan CD-ROM arrives in the mail. But the game lures Michael into committing what may or may not be real acts of murderous violence. It also makes him the plaything of the Trickster

(T. Ryder Smith), a smirking, foppish villain whose manner suggests an aging rock star on a very bad day.

The Trickster springs out of Michael’s television set to ask what are meant to be burning questions (“Real, unreal, what’s the difference, so long as you don’t get caught?”). But Brainscan is less interested in probing the moral implications of Michael’s descent into high-tech hell than in exploiting them in its own high-tech way. John Flynn’s film is more disturbing as a compendium of angry, isolating teen-age tastes than as the cautionary tale of a boy who plays with fire.

Here is what the audience sees during Michael’s first Brainscan adventure: the camera finding its way into a stranger’s house and pausing in the kitchen, where Michael’s hand selects a butcher knife. A trip into the bedroom, where the stranger is sleeping. A slaughter scene, culminating in the mutilation of the stranger. And later, when Michael is no longer playing the game, his dismay at discovering unexplained body parts in his refrigerator. Frank Langella has the insinuating role of a police detective who just knows that Michael has been up to no good.

With its trance-inducing special effects to simulate Brainscan, and with some messy but energetic morphing when Michael finally does battle with the Trickster, Brainscan does approach the mind-glazing effects of an overlong video game. Mr. Furlong, who became a founding father of this film’s video-fun house mentality when he co-starred in Terminator 2, is wrenchingly real as the kind of lonely boy who uses his video camera to spy on the girl next door.

And Mr. Smith brings nasty gusto to the Trickster, a colorful villain despite the fact that his is a distinctly limited appeal. The Trickster is the sort of apparition who breaks his own fingers to test someone else’s ideas of illusion and reality. A little of that goes a long way. Still, when last seen, the Trickster is ready to make more mischief. He may just be in a position to kick off Brainscan 2. 4-22-94

Variety, Joe Leydon – It’s a rare teen horror pic that can be faulted for excessive restraint, but Brainscan may be too tame for the creature-feature fans and slasher devotees who will be drawn by its ad campaign. If Triumph can’t get the word out that this is more of a feel-good date movie than a gross-out monster rally, distrib can expect a fast B.O. fade after fair-to-good openings in regional release. A similar marketing challenge will arise for homevid release.

Director John Flynn and scripter Andrew Kevin Walker clearly set out to establish a new horror franchise a la Friday the 13th and A Nightmare on Elm Street. Just as clearly, they made a conscious decision to tone down the blood and guts, to make their pic more palatable to a wider audience. At least one murder takes place entirely offscreen, while two other deaths are relatively bloodless and entirely accidental.

In theory, such a novel approach to disreputable genre conventions might strike a responsive chord among moviegoers tired of the flood tide of violence in recent film fare. In practice, however, it’s highly doubtful that anybody worried about movie violence would buy a ticket to something called Brainscan in the first place.

Edward Furlong of Terminator 2 fame is well cast as Michael, a 16-year-old horror movie fan, computer whiz and social misfit whose mother died years ago and whose father spends too much time away on business. Michael is quick to respond when he sees an ad in Fangoria magazine for Brainscan, a CD-ROM interactive virtual-reality game that promises to “interface with your subconscious.” Unfortunately, this is one case of too much truth in advertising.

The Brainscan display on Michael’s computer terminal hypnotizes him. While he’s under, he dreams of brutally stabbing a total stranger, then slicing off the dead man’s foot, all of which reps the pic’s only concession to gore hounds. But when he wakes up, he finds it wasn’t really a dream — and the amputated foot is in his refrigerator.

Enter Trickster (T. Ryder Smith), a sardonic bogeyman who looks and dresses like a really ugly ’80s glam rocker (imagine Adam Ant in a Halloween mask). Trickster pops out of Michael’s computer and warns the teen that the games have only just begun. If Michael wants to cover his tracks and stay a few steps ahead of an inquisitive cop (Frank Langella), he will have to play by Trickster’s rules. And rule No. 1 is that Michael must keep playing new Brainscan CDs, for one living nightmare after another.

Once the first murder is out of the way, film becomes an exceedingly tame, only sporadically exciting thriller. The most elaborate special effects are saved until the end, when Michael is literally swallowed up by Trickster while the computer-generated gremlin tries to make Michael kill a pretty classmate (Amy Hargreaves) who lives nearby and hasn’t been too careful about closing her curtains while undressing.

Most of the time, “Brainscan” resembles nothing so much as an undistinguished made-for-cable pic that fails to make the most of a promising high-concept premise. Filmmakers don’t even provide enough good wisecracks for Trickster, who comes across like Freddy Krueger Lite. Wrap-up is surprisingly sunny, suggesting that Brainscan might have worked better as a segment of Nickelodeon’s “Are You Afraid of the Dark?”

Furlong gives a solid and sympathetic performance as Michael. Langella plays it perfectly straight, which works. Smith plays Trickster as a jaded rock star from hell, which works even better. Hargreaves looks and sounds a lot more like the girl next door than actresses in her type of role usually do in this type of movie. Jamie Marsh is aptly Beavis and Butt-Headed as Furlong’s only friend, a fellow horror movie fan.

Rene Daalder’s visual effects and Steve Johnson’s makeup effects are everything they need to be. A good thing, too, because that may partially appease horror buffs disappointed by the pic’s small body count. Other tech credits are adequate. 4-22-94

Chicago Sun-Times – Roger Ebert: Any movie about computers starts out with a technical problem: How exciting can it be to show someone sitting at a keyboard and staring at a screen? “Brainscan,” a movie about a teenager who gets trapped inside a deadly computer game, solves the problem by providing the Trickster, a cadaverous character who looks something like Alice Cooper on the third day of the wake. The Trickster materializes from a CD-ROM computer game (or says he does) and hangs around the kid’s room, sticking his finger in an electric socket for entertainment.

The kid’s name is Michael. He’s played by Edward Furlong (of “Terminator II”), and like a lot of teenagers he has carved out a corner of the family home as his private domain. It’s the attic, where he has thousands of dollars worth of equipment, including a fast computer with state-of-the-art audiovisual capabilities, and a remotecontrolled video camera that can spy on the teenage girl next door and send the picture to a handy TV monitor. Teenagers are really getting lazy when they can’t even peek out through the blinds themselves.

Michael is a video game buff, with a subsidiary interest in horror films. When he’s caught showing a violent slasher film to his high school class, he’s hauled up in front of the principal, who sternly demands the title of the film. “Death, Death, Death,” Michael says sullenly. “Part Two.” What these movies are basically offering is a digitalized update on those dream sequences and fantasy scenes in old horror movies: When the hero wakes up sweaty and gasping, does it matter if it was “only a dream” or “only a CD-ROM video game?” “Brainscan” is interesting not so much because of the plot, the murders, and the Trickster, as because of its portrait of a teenage boy living at one remove from the world. The computer provides him with his interface with reality, so that, in a sense, he is the game. I had a sinking feeling during that scene where he trains his video camera on the girl next door, and feeds his signal into a monitor. In his mind, I fear, he was thinking, not “what a bod!” but “what a signal!” 4-22-94

Washington Post – Desson Howe:”Brainscan,” a teensploitation horror picture about dangerous dabblings in virtual reality, wants to jolt the young and jaded — those weaned on Freddy Krueger and the graphic brutality of such video games as Mortal Kombat. But this weird amalgam of high-tech fetishism, special-effects gee-whizzery and horror-fest camp is too uneven — and unbelievable — to get anyone’s hard drive going.

Sixteen-year-old Michael Brower (Edward Furlong) is sensorially overloaded with video games and horror films, but as far as human contact goes, he’s undernourished. His mother’s dead. His father’s always away on business. His idea of dating is to secretly videotape pretty neighbor Kimberly (Amy Hargreaves) as she oh-so-conveniently undresses before her open window.

When his friend Kyle (Jamie Marsh) tells him about an interactive computer game (Brainscan) that promises the “ultimate experience,” Michael gives it a reluctant try. But after popping in the CD-ROM disk, he undergoes the snuff-fest thrill of his life. Hypnotized by the images, and goaded into vicarious action by a disembodied taskmaster, Michael finds himself looking through the eyes of a serial killer. In this game, he is told, he must break into a house and murder the sleeping inhabitant within a limited time frame. Michael complies. Michael stalks a middle-aged man in an upstairs bedroom and repeatedly stabs him. Then, forced into violence by the mysterious instructor, Michael hacks off the man’s foot.

Waking up from this trancelike pastime, Michael is shaken but exhilarated. When a news program shows grisly footage of the murder, however, his joy turns to horror. Michael becomes convinced that he has actually committed the killing. At this point, malevolent, wisecracking Trickster (T. Ryder Smith), Michael’s virtual-reality host, materializes out of the television screen. In an increasingly unbelievable chain of events, he bullies Michael into playing — and killing — again. Meanwhile, back in the real world, suspicious Detective Hayden (Frank Langella) sniffs around Michael’s house for information.

“This isn’t a game anymore,” says Michael ridiculously late in the proceedings. “This is lots of crimes.”

“Brainscan,” directed by John Flynn (“Lock Up) and written by Andrew Kevin Walker and Brian Owens, is lots of crimes too. Furlong has an annoyingly sissy presence, and Trickster’s moussed mane, shorn sides, nose ring and flattened nose suggest an uninspired composite of Dennis Miller, Charles Manson and Mick Jagger (“Please allow me to introduce myself,” he says to Michael).

There are other creative misdemeanors, such as the pseudo-“Twin Peaks” chords on the soundtrack and the sexual exploitation of Kimberly — who finds herself in constantly demeaning poses. In the most ludicrous instance of this, Michael finds her asleep with her blouse unbuttoned to bare her brassiere.

After reveling in gratuitous violence and girl-ogling, “Brainscan” attempts to redeem its guilty pleasures with false, socially correct admonitions — about how we are all susceptible to a little murder and titillation, how technology desensitizes us to violence and morality, and so on. But if the filmmakers really believed this stuff, they wouldn’t have made this movie, would they?

“Brainscan” is rated R and contains graphic violence and mutilation, partial nudity and not nearly enough special effects. 4-22-94

Washington Post – Joe Brown: Freddie’s dead, Jason’s over, Chuckie’s out . . . Meet the new kid on the horror block: Trickster, a video villain from within the computer screen (he looks a bit like Dennis Miller after a few days in the ground). Played by T. Ryder Smith, Trickster provides much of the fun in “Brainscan,” a thoroughly formulaic horror movie juiced up with virtual reality techno-toys and MTV attitude.

Edward Furlong, better known as the kid in “Terminator 2,” plays misfit loner Michael Bryer. His mother died in a car accident and his father is always away working, leaving the boy to retreat into a world of computers, fantasy and horror. His room is a teen guy’s fantasy, an attic crammed with state-of-the-art computer gear, neighborhood-rattling stereo equipment and comic books.

Michael’s best friend alerts him to an ad in Fangoria magazine for a computer game called Brainscan that taunts him to “satisfy your sickest fantasies . . . enjoy the fear.”

So the young anti-socialite dials 1-800/555-FEAR, and after the set of four CD-ROM discs arrive, he plays the first installment. Called “Death by Design,” it’s a virtual reality experience of a murder — with a killer’s-eye view. Furlong, whose mask-like face and hard, unreachable eyes are the image of contemporary teenage anomie, comes to in front of his screen and realizes it’s not just a game. He’s guided and goaded by the gleefully gauche Trickster, a campy comic book creation who sizzles out of the screen and says “Please allow me to introduce myself . . . ” Frank Langella appears as a detective who notices Michael at one too many crime scenes.

“Brainscan” is as brain-dead as they come, but director John Flynn keeps it consistently watchable with clever gimmicks and gruesome gags. The movie’s into-the-screen premise may have been lifted from David Cronenberg’s “Videodrome,” but the technology is flashy and witty and the camerawork is consistently interesting. And those who faithfully follow the genre (and you know who you are) will be grateful that Flynn has done away with the hoary theme of monster-murder as reprisal for teenage sex. 4-22-94

Deseret News, Salt Lake City – Chris Hicks: What if video games did more than simply cause you to be inert while frying your brain? What if they could actually be used as a vehicle for murder?

That’s the “what if?” premise behind “Brainscan,” which seems to aspire to be a cautionary tale but settles for being a half-baked “Nightmare on Elm Street” ripoff — complete with Freddy Krueger clone.

“Brainscan” is yet another in what is fast becoming a sub-horror genre, the video game murder movie, most prominently exemplified by “The Lawnmower Man” and “Ghost in the Machine.” But if they weren’t much, “Brainscan” is even less.

Edward Furlong, the kid in “Terminator 2” and the oldest of Kathy Bates’ children in “A Home of Our Own,” stars here as a latchkey teen who has mastered every video game there is. (His other hobbies are gory horror films and watching the teenage girl next door undress at her open window.)

So, when he hears about “Brainscan,” he is naturally skeptical. But, of course, he gives it a try and discovers a hypnotic CD-ROM that creeps into his subconscious as he witnesses a brutal murder through the eyes of the killer. The object is to complete the dastardly deed and return home within the allotted time frame. (Serial killer training, the next big leap in interactive technology; a lovely idea.)

At first, Furlong is wildly enthusiastic about the game, but then he sees the 6 o’clock news and realizes it wasn’t just a fantasy — it really happened, and right in his neighborhood. Further proof is provided by grisly evidence in his freezer.

Soon, Furlong is pushed to take the game to new levels by that Freddy Krueger clone, The Trickster (T. Ryder Smith), who initially appears as a hologram, and then proves to be a demon of some sort, if not the devil himself.

The Trickster is also not above planting clues for the local police (headed by detective Frank Langella), as Furlong continues to play the game and his victims become close friends instead of strangers.

And as with Freddy Krueger, toward the end of the “Nightmare on Elm Street” series, The Trickster becomes less well defined as “Brainscan” moves along. Is he merely mischievous or truly evil? It’s hard to laugh at the sick one-liners if the latter is true, as seems to be the case most of the way.

And Furlong’s brooding style is not particularly appealing. You may feel somewhat sorry for his character’s dilemma, but you will probably never identify with him.

That leaves only the special effects, and nothing here is as impressive as “Ghost in the Machine” or “The Lawnmower Man.” This is pretty routine stuff. 4-22-94

Newsday – John Anderson: The medium is the massacre: Interactive video game is murder on a reclusive high school misfit. Great concept, but it gets lost in horror-movie kitsch. With Edward Furlong, Frank Langella, T. Ryder Smith, Amy Hargreaves. Story by Brian Owens. Screenplay by Andrew Kevin Walker. Directed by John Flynn. 1:35 (some nudity, more violence). At area theaters. FOR MICHAEL (Edward Furlong), the high school techie-cum-mass murderer of “Brainscan,” cocooning with one’s computer is about control. And he’s made it an art: When he plays the voyeur with the girl next door, he not only videotapes her, he watches the playback on his console, buried inside his attic room, even before she’s put on her clothes and disappeared from view.

No, there can never be too much control, too many degrees of separation, too many layers of media between a boy and his loved ones. His father, who travels, is just a voice on the phone. His mother, the stuff of flashbacks, died in the same car wreck that left Michael’s right leg crippled and, presumably, contributed to his antisocial attitude and death obsession. Except for running his high school’s soon-to-be-outlawed Horror Club – where they watch such primal works as “Death, Death, Death, Part II” – his only human contacts are his soon-to-be-slacker buddy Kyle (Jamie Marsh) and that nubile neighbor Kim (Amy Hargreaves). Who, by the way, knows he’s watching.

Turning Michael’s reclusive, insular little electronic world inside out is Brainscan – “the ultimate experience in interactive terror” – which transports Michael into virtual reality, and into a neighbor’s house, where he slaughter’s the homeowner in his sleep. “It was sick,” Michael says, when he thinks it’s a game. And then he sees the news broadcast.

At this point, “Brainscan” is less stock horror than satire – HAL as a CD-ROM, “The Eyes of Laura Mars” on a color monitor – and you can’t help getting a little satisfaction in watching the ennui-ridden Michael being shaken to his shoes. But when he resists the second step on the Brainscan menu, the Trickster (T. Ryder Smith) appears, a 3-dimensional grotesquerie who threatens and cajoles Michael into playing all four stages of the murderous game. And the film becomes more of a generic blood bath.

Furlong (“Terminator 2”) exudes a totally inconsequential physical presence, which helps make Michael’s general disenchantment believable. It also adds an ominous aspect to his confrontations with Detective Hayden, played by the hulking Frank Langella, whose animal quality terrifies the cerebral Michael, and makes their cat-and-mouse game all the more tense.

There’s cleverness in Andrew Kevin Walker’s script – when Michael calls the Brainscan number and gets a live voice, he’s both appalled and apologetic: “Sorry,” he says. “I thought you were a machine.” And both Marsh and Hargreave are refreshingly real. But given T. Ryder Smith’s over-the-top Trickster, the incongruous elements of teen romance/angst and gratuitous gore, what might have been a tart sendup of modern obsessions becomes an unpalatable soup. 4.22.94

Philadelphia Daily News – Gary Thompson: The briefly promising “Brainscan” uses interactive CD technology as the springboard for a horror story, only to falter in a lame attempt to create another Freddy Krueger movie franchise.

The new bogey man is the Trickster, an electronically generated hoodoo issued by an interactive-CD-based computer program called Brainscan that invites the user to walk in the footsteps of a stalking murderer.

A teen computer hobbyist and horror freak (Edward Furlong) tries the program, which allows him to prowl and kill like a homicidal maniac. The lad then discovers his fantasy murders bear an uncanny resemblance to actual neighborhood slayings.

Is he the culprit? Or is it the Trickster, a guy with a melted face and red punk hair who pops out of the CD program? He’s meant to be scary, but the only scary thing about him is that he looks like Keith Richards.

“Brainscan” takes a few tentative steps toward exploring the relationship between voyeuristic violence and real violence, but gives up. It ends up as just another collection of Krueger-esque witticisms, gross-outs and fake-outs.

For hard-up genre fans only. 4.22.94

Philadelphia Inquirer – Desmond Ryan: At a time when most horror films are demonstrably brain-dead, Brainscan arrives with the makings of a good idea.

Unfortunately, director John Flynn and his writer Andrew Kevin Walker don’t make much out of the interesting and topical issue they raise. Where most films in the genre make a virtue of being as unreal as possible, Brainscan poses a question about virtual reality games. What psychological impact do violent games have on gullible teens and, more importantly, what are the possible consequences in behavior once the players return to the real world?

It should be noted that a horror film is hardly the best place to air this complex and intriguing discussion. After all, such movies were being chastised for encouraging violence – or at least numbing people to its results – long before anyone even heard of virtual reality. Flynn doesn’t help his case by resorting to the customary servings of gore, including a severed human foot tastefully lodged between the milk and the mustard in a refrigerator.

Before commercial considerations and the requisite blood-slinging turn the movie into more of the same, Brainscan explores its slick premise inventively. Michael (Edward Furlong) is a lonely teenager whose offputting, antisocial manner leaves him with very few friends. His life revolves around the computer that runs his games.

Michael’s obsession with these games means he already has a tenuous hold on the real world. When a CD-ROM game called Brainscan arives in the mail, he plays it and finds himself living out the ultra-realistic scenario of a gruesome murder in which he is cast as the killer. Emerging from the session in a cold sweat, Michael turns on the news and finds out the murder did, in fact, happen.

The remainder of Brainscan is a collection of addled implausibilities as the police, led by a slumming Frank Langella, latch on to Michael as a suspect and a Faustian presence called Trickster urges him to plunge deeper into the deadly game. By the time play is over, the fun and the point have long since disappeared. 4.23.94