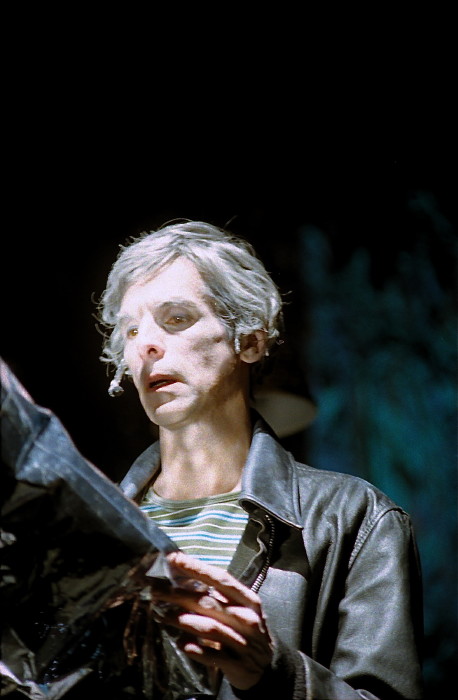

Photos by T. Ryder Smith/The Hinge Collective

Excerpts from the reviews

See full reviews below

“A boggling and occasionally baffling evening of theatre . . . seeks to recreate the heyday of Andy Warhol’s Factory in look, sound, and spirit. In terms of all-encompassing theatricality, they’ve succeeded admirably. Uncompromisingly directed, [this] is a work where , despite glimpses of a traditional narrative, the line between audience and performer is heavily blurred. . . With silver pillows adorning the floor, foil-covered walls, and a number of television monitors and projection devices, the set encourages the audiences’ own emotional experimentation with art and the attempts to find a boundary it feels comfortable with. . . [The piece] reaches a level of intriguing complexity and atmospheric effectiveness [and] bursts with visual, aural, and intellectual interest.” Matthew Murray, Talkin’ Broadway

“Presents the Solanas-Warhol encounter as a kind of Greek tragedy . . . set in Warhol’s Factory, complete with walls of crinkly foil, “superstars” in shades, and spectators perched in the round on couches, chairs, and pillows – All very groovy. . . T. Ryder Smith seems appropriately disembodied as Andy, while Juliana Francis damps down her glamour to play a fierce and indecorous Valerie. Houppert’s script makes them seem polar opposites: he cool, successful, deadpan verging on catatonic; she uncool, failed, a motormouth . . . Despite these polarities, the play does not seem schematic . . . “ C. Carr, The Village Voice

“Like a high-art high-school fling between a popular guy and a freaky girl . . . Andy feeds on Valerie’s energy and power, using it to fill up the void of coldness that exists in his own heart. Andy is stillness and Valerie is motion . . . The audience is seated cheek-by-jowl with the actors, silver balloons and a raucous rock ensemble. . . complete with booze and dancing hotties and viewers being asked if Andy can take their picture . . . Much credit must be given to Juliana Francis and T. Ryder Smith, who create within the iconic shells of Solanas and Warhol creatures of touching depth. Francis gradually reveals the vulnerability beneath Solanas’ brittle exterior in a kind of psychological fan dance . . . Smith’s Warhol is an apt foil; where the temptation to play a spacey Andy for pure parody is enticing . . . Smith displays a shrewd and subtle awareness of the distance between Andy Warhola of Pittsburgh and Andy Warhol, Pop Artist. . . The elements of the narrative come together to create a picture of the era as a time of limitless intellectual promise . . .” Jeff Lewonczyk, nytheatre.com

“Francis’ grandly wired Solanas [pours] her story out to The Reporter, and the piece travels back in time, showing the evolution of the conflicted Solanas-Warhol relationship. These three performers create a fascinating complementary triptych of character traits. T. Ryder Smith is the simultaneously distant and engaging Warhol . . . Director Nunns does a superb job of breaking down the fourth wall, and combined with the excellent period costumes and the pulsating lighting design, one feels as if one has become part of the Factory party. That counts as art.” Andy Propst, Backstage

“A cast of fine downtown actors almost saves ‘Tragedy’ from drowning in muddy chaos and period cliches. . . Juliana Francis captures . . . the spirit of punk fury . . . T. Ryder Smith is delicious as the listless, sarcastic Warhol. These two actors prove there’s a great play or musical in this historical footnote. But this definitely isn’t it.” David Cote, TimeOut NY magazine

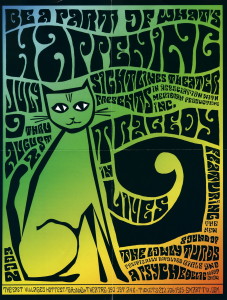

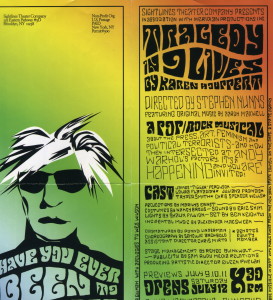

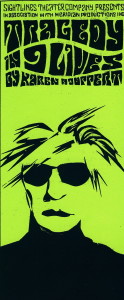

Publicity

NYTheatrewire, Marilyn Abados – “Tragedy in 9 Lives” is Karen Houppert’s new pop/rock music theater work set at Andy Warhol’s Factory, circa 1968. It re-creates the “happenings” of that era as audience members, including Warhol himself, find themselves voyeurs, eavesdropping on a cast of characters including The Chelsea Girls, militant feminist Valerie Solanas, and the new journalists who were seduced by the ’60s scene. For 15 minutes, in Warhol’s New York, art, feminism, politics and the press intersected in an exhilarating and dangerous way. “Tragedy” is a rare and exciting, contemporary music-theatre-performance event that taps the experimental vibe of the late 1960s, an unprecedented time when the borders between “high” and “pop” were fluid and the possibilities seemed endless. The cast features Juliana Francis, T. Ryder Smith, James “Tigger” Ferguson, Laura Flanagan, and Chris Spencer Wells. Sightlines Theater Company was founded in 1996 by its Artistic Director Eileen Phelan with a mission to produce theater that is inspired by a contemporary or historic event, cultural trend or significant person. In addition to”Permanent Visitor” and “Snatches,” Sightlines’ previous productions include Kia Corthron’s “Cage Rhythm,” Lizzie Olesker’s “Dreaming Through History,” Naomi Wallace’s “One Flea Spare” and “American Rose: Stories of the Gals on the Homefront,” plus many readings and workshops of new plays.

Offstage

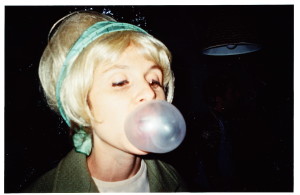

Some photos taken by “Andy” during the performances:

Full reviews

Backstage, Andy Propst – “Can a dinner party be art?” asks Andy Warhol in Karen Houppert’s multimedia musical, ‘Tragedy in 9 Lives’. Houppert and her team answer in the affirmative by showing that spying on the goings on at Warhol’s famed Factory can be an engaging and entertaining way to spend an evening. Set designer Ben Keightley has converted P.S. 122’s ToRoNaDa space into the Factory, complete with aluminum-foil-covered walls. The audience sits on couches, mattresses, or on the floor. Marilys Ernst’s video and projections are seen on TV screens that rest at angles on the playing area or its walls while the action plays out. At one end of the space, Aaron Maxwell and Stephen Nunns (who has also directed), joined by Alexander MacSween, play their evocative rock score. The evening begins with the famed shot that Valerie Solanas fired at Warhol. Soon, Juliana Francis’ grandly wired Solanas is pouring her story out to a reporter, played with sympathetic geekiness by Chris Spencer Wells, and the piece travels back in time, showing the evolution of the conflicted Solanas-Warhol relationship. (T. Ryder Smith is the simultaneously distant and engaging Warhol.) These three performers create a fascinating complementary triptych of character traits. When not concentrating on these relationships, the piece shows the doings in the Factory—the making of Warhol’s art. Here, James “Tigger” Ferguson, Laura Flanagan, and Chris Mirto all provide period flavor and the requisite late-’60s loopiness. For context, one hears portions of Solanas’ writings and excerpts of reviews of Warhol’s work. Director Nunns does a superb job of breaking down the fourth wall—characters proffer fortune cookies to the audience—and combined with Nancy Brous’ excellent period costumes and Shaun Fillion’s pulsating lighting design, one feels as if one has become part of the Factory party. That counts as art. 8.15.03

CurtainUp, Les Gutman – “The male artist: a contradiction in terms”. -Valerie Solanas. As I ventured from the subway to P.S. 122, I traversed Saint Marks Place, passing the old Polish Social Hall (called the Dom) where Warhol made his first splash with an extravaganza called The Exploding Plastic Inevitable. The increasingly shiny block reveals few recollections of that period to its current pedestrians, many of whom could be the grandchildren of those who had been there in 1966. Entering the Mabou Mines space at P.S. 122, where ‘Tragedy in 9 Lives’ is being presented, is like walking into a time warp. The space is converted into a reasonable facsimile of Warhol’s Factory: scattered seating mixed with various beds, perches and a bar, most everything covered in aluminum foil. (We are offered beer, $3, by women dressed in silver lamé mini-dresses.) At one end, a rocking band plays and, on this night at least, what seems like a busload of fresh-faced teenagers fills the floor. For those interested in Andy Warhol, his compadres and hangers-on, there exists an almost endless supply of raw material: the product of his own voyeuristic obsessions and a healthy dose of media attention. It’s been well over fifteen years since Warhol’s death, which is enough time for some perspective. We’ve had a number of films and documentaries in the last few years. Now we get Karen Houppert’s play, which is not so much a re-examination as a re-visit. If the design achieves verisimilitude, so does everything else. Warhol’s film documentation of his friends was extensive; it was random and filled with drug-addled rants. As one critic related, it conveyed a “contagious lethargy”. The same qualities obtain in Houppert’s ‘Tragedy’. Unfortunately, they don’t make great theater. The challenge in presenting a show such as this is to find a way to make it compelling; this was not a call Ms. Houppert, her director, Stephen Nunns, and company chose to embrace. So despite a few successful scenes, and a few fine performances, much of the show is an exercise in tedium. Some of the show’s best segments involve Valerie Solanas (Juliana Francis), with material culled from various interviews and her SCUM Manifesto. Oftentimes, it seems it is she, rather than Warhol (T. Ryder Smith), who is the focus of the piece. [T note: She was.] Ms. Francis effectively and believably conveys the over-the-edge Solanas. The same cannot be said for the rendition of another Warhol regular: Ondine (James “Tigger” Ferguson); he’s all hackneyed spectacle, and one of the major testers of our patience. Smith, however, finds just the right tone for Warhol: aloof and elusive. The show’s major invention is a reporter (Chris Spencer Wells), who arrives straight-laced and descends into a sort of hip hell. Wells is the show’s bright star, and his transformation is an impressive sight to witness. One might have hoped that Ms. Houppert would have utilized him more effectively to create structure and focus, but as he deteriorates, so does the storytelling. The show is billed as a musical, which I suppose technically it is, but its six songs (written apparently in collaborative jam sessions involving much of the cast and band) don’t do a great deal to aid the story beyond adding another layer of ambiance. Notwithstanding, I liked much of the music, and can also report that Mr. Wells, in addition to being a welcome addition to the New York acting scene, can also sing quite well. When Cher saw The Exploding Plastic Inevitable, she is reported to have said “It will replace nothing — except maybe suicide.” An overstatement here at least, but not that far off. It would take more than a bottle of beer to make this the happening it seems to want to be. 7.10.03

NYTheatre.com, Jeffrey Lewonczyk – Considering that Valerie Solanas shot Andy Warhol, it’s odd to conceive of their relationship as a romance. But all great shootings are triggered by some kind of passion, and ‘Tragedy in 9 Lives’, Karen Houppert’s pop/rock music theatre piece, envisions this passion as a twisted form of infatuation. It reads like a high-art high-school fling between a popular guy and a freaky girl, a psychedelic ‘Pretty in Pink’. Andy and Valerie meet, and they are each hesitantly intrigued by something in the other. Valerie tries to convince him to read her SCUM Manifesto, outlining her revolutionary plan to exterminate the male sex, but he tells her he’d prefer the synopsis. Thereafter he quietly absorbs her rants against the patriarchy, and she revels in his attention. Soon they’re going on field trips to the Met together, where they share their views on art. Andy takes photos of Valerie, who finds a creative way to affectionately flip him the bird with every shot. Houppert depicts the two characters as desperately needing something in the other. Valerie basks in the glow of Andy’s fame and talent, which also serves as a symbol for her to rail against. Andy feeds on Valerie’s energy and anger, using it to fill up the void of coldness that exists in his own heart. Andy is stillness and Valerie is motion, yin and yang spinning in place and balancing each other out. But this is America, after all, so something’s got to give. Someone gets shot, and, far from ending his career, the event cements his celebrity, while the shooter slowly devolves into obscurity. Director Stephen Nunns stages the piece in a studio with tinfoil wallpaper, in which the audience is seated cheek by jowl with actors, silver balloons, and a raucous rock ensemble. The play’s opening moments are an evocation of a Factory party, complete with booze and dancing hotties and viewers being asked if Andy can take their picture. A level of low-key interactivity remains throughout, in such scenes as Solanas hawking the SCUM Manifesto to ladies in the audience while hissing at the menfolk. Intercutting primary source material with fictional speculation, the show has the potential to come across as an arch riff on the myth of the Sixties rather than a living, breathing three-dimensional artwork in its own right. This is why much credit must be given to Juliana Francis and T. Ryder Smith, who create within the iconic shells of Solanas and Warhol, respectively, creatures of touching depth. Francis gradually reveals the vulnerability beneath Solanas’s brittle exterior in a kind of psychological fan dance, ensuring that we see the human behind the harangue. She moves and speaks like only a true outsider could; her jittery, desperate verve fuels the show. Smith’s Warhol is an apt foil; where the temptation to play a spacey Andy for pure parody is enticing (see David Bowie’s turn in the film Basquiat), Smith displays a shrewd and subtle awareness of the distance between Andrew Warhola of Pittsburgh and Andy Warhol, Pop Artist. Orbiting around this duo is a square but open-minded Reporter, portrayed by Chris Spencer Wells (who is no doubt tired of hearing that he looks like Drew Carey in that getup). Initially more conceit than character, the Reporter acts as a mouthpiece in transcriptions of interviews with and articles about Warhol and Solanas, until the prevailing spirit of the times liberates him, with comical and disturbing results. Rounding out the principal cast are James “Tigger” Ferguson as Factory regular Ondine and Laura Flanagan as a trio of Factory females. These two performers reenact scenes from Warhol’s film ‘The Chelsea Girls’ that highlight the ambiguities and dangers of the precarious path taken by many artists in the Sixties. The elements of the narrative come together to create a picture of the era as a time of limitless intellectual promise; of course, for each person this promise existed in a different direction, and the ensuing conflict ensured that everyone eventually fell back down to earth. The music, written and played by house band The Lowly Turds, sounds great (if occasionally anachronistic in the carefully contrived period setting), but the lyrics have a tendency to pound points home a bit too glibly. It’s in the interplay of the performers with themselves, with the text, with fiction and reality, and with the audience that the pleasure and excitement of the show reside. 7-11-03

Talkin’ Broadway, Matthew Murray – The live music being played when you enter the ToRoNaDa Theater at PS 122 may be overly loud, but it’s certainly not superfluous. It’s but the initial audio element of a boggling and occasionally baffling evening of theatre. It’s one of many integral parts of Karen Houppert’s ‘Tragedy In 9 Lives’, the new production by the Sightlines Theater Company that seeks to recreate the heyday of Andy Warhol’s Factory in look, sound, and spirit. In terms of all-encompassing theatricality, they’ve succeeded admirably. Uncompromisingly directed by Stephen Nunns, ‘Tragedy In 9 Lives’ is a work where, despite glimpses of a traditional narrative, the line between audience and performer is heavily blurred. Yes, the audience is asked to sit and listen to characters’ interpretations of events, but while watching, don’t they become a part of what they’re observing? It’s that question that the play seeks to address, if not necessarily answer outright. With silver pillows adorning the floor, foil covered walls, and a number of television monitors and projection devices, the set (by Ben Keightley) encourages the audience’s own emotional experimentation with art and the attempts to find a boundary it feels comfortable with. The production’s ensemble members, clad in black and silver in the tempting/taunting late 1960s style (by Nancy Brous) toe that line as well before the performance starts, putting on their own shows with flashlights, dancing, and writing about on the furniture. Where reality stops and art begins is also an issue of vital importance to the characters, including Warhol himself (T. Ryder Smith) and militant feminist Valerie Solanas (Juliana Francis). The physically violent results of their professional and personal intermingling are already the stuff of modern art history; from first meeting to final gunshot, in terms of sheer facts, ‘Tragedy In 9 Lives’ provides no new insights. Houppert and Nunns are far more interested in the effects of their art on the lives of others. Warhol’s almost improvisatory method of filmmaking enlists the work of Ondine (James “Tigger” Ferguson), who can’t hold back his own rage when faced with criticism he easily applies toward others, while a reporter (Chris Spencer Wells) becomes so enmeshed in the artistic freedom (and, yes, the drugs) of the period that he can’t help but become a part of it. But their presence – like the video animations of Warhol’s works or any of the show’s six songs (with titles such as “One Blue Pussy,” “With A Gun,” and “I Shot Mary Magdelene”) – contribute enormously to the panoply of the late 1960s underground culture the show documents. If certain characters or depicted situations don’t always contribute a great deal dramatically, it’s impossible to imagine ‘Tragedy In 9 Lives’ reaching the same level of intriguing complexity or atmospheric effectiveness if even one were missing. Houbbert’s writing in those segments is strong enough to call attention how slowly-paced and abstruse her direct work is with the primary Warhol-Solanas plot; the rest of the show has the tendency to move around most of these moments. The muted energy Smith and Francis bring to their roles results in a fair amount of one-note, occasionally stammering speech which may be historically accurate, but is not always pleasant to listen to for long periods. Earlier this year, the Public’s ‘Radiant Baby’ provided a campier, almost vaudevillian Warhol; hardly an ideal solution for this play, it was a more creative way of solving the problem of a difficult historical figure. But ‘Tragedy In 9 Lives’, bursting with visual, aural, and intellectual interest, still serves as an intriguing tribute to Warhol’s work and foibles, even though the show is more interested in examining from as many angles as possible the artistic movement Warhol inspired, and the one he was a part of. 7-03

TheatreMania, Barbara & Scott Siegel – Someday, there will be a play or a movie or a book about Andy Warhol that will reveal something about the man that will move an audience to tears — or, at least, bring us to a deeper understanding of the most enigmatic figure of 20th century art. The most recent stylish-but-empty attempt to find meaning in the Warhol experience is Karen Houppert’s new play ‘Tragedy in 9 Lives’, a production of the Sightlines Theater Company. The tragedy is that audiences may accept this play’s sizzle for substance. In a purely theatrical sense, there is plenty of fat to fry in Houppert’s recreation of the downtown art scene of 1967-68, when fractured feminist Valerie Solanas entered Andy Warhol’s orbit and eventually tried to assassinate him. The play uses their relationship as an entry point and central metaphor for an artistically dangerous time when morality was graded on a curve and no one knew who was actually doing the grading. Warhol was instrumental in changing our definition of art and his lifestyle was an embodiment of the changing times, so the playwright dives right in to that frenetic world; we become witnesses to a clash of extreme personalities, artistic flimflam, and whacked socio/political theories. With the help of director Stephen Nunns, Houppert gives us all of that and more amid the whirl of cameras and the omnipresence of drugs as every character in the play exhibits a desperate need for attention. The production is nothing if not atmospheric. Nunns establishes about half a dozen playing spaces within P.S. 122’s small ToRoNaDa Theater. Patrons are seated on couches and chairs that zigzag in and around those spaces, creating a genuine sense of audience inclusion. At one point during the performance we attended, a character called “The Reporter” (Chris Spencer Wells) was taking notes at a table right next to us while we were also taking notes. The doppelgänger effect of this bordered on the surreal. The narrative is disjointed but not difficult to follow. Its main thread follows the disquieting relationship between Warhol (T. Ryder Smith) and Solanas (Juliana Francis). He was clearly fascinated by her and had a somewhat innocent interest in what made her tick; of course, as we now know, the tick was a time bomb waiting to go off. Solanas was the author of The SCUM Manifesto (Society for Cutting Up Men). Her rhetoric was violent yet surprisingly articulate. She was on the lunatic fringe but could pass for a would-be revolutionary with artistic pretensions — or was it the other way around? In the late 1960s, it was hard to tell. The play runs into a problem that any dramatization of Andy Warhol’s life presents: Warhol was a virtual zombie. Put this guy and Solanas in any scene together and Solanas, possessed by dark passions and the energy to match them, will naturally dominate every moment. ‘Tragedy in 9 Lives’ has has no choice but to be about her because her character simply demands it, while the Warhol character happily recedes and watches. To his great credit, T. Ryder Smith gives dimension to Warhol, finding humor and attitude in his self-effacing weirdness. This is a drama with music, and Warhol has a witty pop song, “When Mom Was Mom” (Aaron Maxwell/T. Ryder Smith), that lends him further dimension and charm. Nonetheless, Solanas is still the compelling force of the play, especially in Juliana Francis’s tempestuous performance. When Francis sings (and dances) “Fuck Me Up,” which she wrote in collaboration with Maxwell, she really seems to mean it. As a recreation of its time, this show has merit. As an opportunity for Nunns to display inventive staging, it has additional merit. The production is also a worthy vehicle for Smith, Francis, and Wells. But ‘Tragedy in 9 Lives’ really has very little to say and fails to convey even one tragedy, let alone nine. The best sequence in the play, in fact, has nothing to do with either Warhol or Solanas but rather with the reporter and a mysterious “theorist” played by Laura Flanagan. These two discuss art with considerable insight, making one wish that the play were about them. 7.14.03

Village Voice, C. Carr – SCUM Goddess. Who’s the Villain? Who’s the Saint? At one time, Valerie Solanas seemed the feminist ghost least likely to rise from the grave. The one and only member of the Society for Cutting Up Men, she was just too mad and too bad. But less than 10 years after her death in 1988, this unlikely spectre began to stir. First came Mary Harron’s film I Shot Andy Warhol, then Carson Kreitzer’s play Valerie Shoots Andy, and George Coates’s all-female musical version of Up Your Ass, the play Solanas accused Warhol of stealing. Now Karen Houppert adds ‘Tragedy in Nine Lives’, which presents the Solanas-Warhol encounter as a kind of Greek tragedy. Of course, what lives on after all these years is Solanas’s Medea-like fury and poisonous resentment. The author of the SCUM Manifesto is probably destined to be an icon of female rage for as long as sexism lasts. ‘Tragedy in Nine Lives’ is set in Warhol’s Factory, complete with walls of crinkly foil, “superstars” in shades, and spectators perched in the round on couches, chairs, and pillows—all very groovy. And it’s a musical. A three-piece rock band, the Lowly Turds (Alexander MacSween, Aaron Maxwell, Stephen Nunns), adds a Velvet Underground mood and accompanies the six songs. And we come in knowing the tragedy we’re headed for. Houppert is also a journalist (and formerly a colleague here at the Voice) whose previous stage work includes ‘The Packwood Papers’. Based on the sexual harassment investigation into Senator Bob Packwood, that script incorporated actual text from his lurid and pathetic diaries. In ‘Nine Lives’, Houppert quotes from the SCUM Manifesto and newspaper articles, but her scenarios aren’t intended to re-create the real relationship between Warhol and Solanas. The play presents Warhol as fascinated by her. In real life, apparently, he just tolerated her. T. Ryder Smith seems appropriately disembodied as Andy, while Juliana Francis damps down her own glamour to play a fierce and indecorous Valerie. Houppert’s script makes them seem polar opposites: he cool, successful, deadpan verging on catatonic; she uncool, failed, a motormouth. Warhol says his highly praised work has no meaning, while Solanas brandishes a ratty manuscript no one wants and thinks it holds the key to the universe. Despite these polarities, the play does not seem schematic. Still, Warhol begins to look like a logical target for her. Again, that isn’t true to life, since she actually set out to shoot her publisher but couldn’t find him. Warhol was available. His work has conceptual weight, while hers is just a screed. Yet both are visionary in their own way. When I first read the SCUM Manifesto in the early ’70s, I thought it utterly repellent. But like many rants, it contains a kernel of unvarnished truth—about the corroding impact of sexism. There’s an Ondine character in this play whose anti-woman diatribes almost balance Solanas’s screwy man-hating. And a Reporter appears, to misunderstand and misrepresent everyone to Middle America; his drug-induced transformation from man to drag queen, if not woman, seems the least thought out part of ‘Nine Lives’. Another complaint Solanas has with Warhol and Pop artists in general is that they’re ironic. They don’t believe in anything. This, she says, will be the ruin of the ’60s and the end of questioning the status quo. // No doubt she’d start shooting up the joint if she saw a performance of Marc Spitz’s farce, Gravity Always Wins. But remember—she’s a nut. ‘Gravity’ is a demented, untelevisable sitcom in which dysfunction is pushed to the max. Every character in this show would do well to be divorcing, departing, or trying to get disowned. Of course, if they did that, where would the fun be? I can’t divulge much plot without giving away the jokes for those who take their humor very dark. Suffice it to say that it opens with a father and his two grown sons seated around a kitchen table, the father demanding that everyone speak French, though he himself does not know French, though he insists that he is in fact speaking French. Dad, by the way, is dressed like Michael Jackson (the white-glove era) and becomes more Michael-ish as the play progresses. The packed house I saw it with was loving it; I was not. 7.22.2003

[previous] [next]