Photos by Carol Rosegg and Sara Krulwich

Excerpts from the reviews

Full reviews are below

“The screen star of all those “Harry Potter” movies brings a disarming vulnerability and touching desperation to the role of Alan Strang . . . Director Thea Sharrock, taking a cue from the original staging, has given the play a compelling, arenalike flavor. Some audience members sit in two tiers above the stage and look down on the action. The story is played out on a physically spare set (designed by John Napier) containing a collection of moveable black cubes that serve as furniture. The exquisite lighting, much of it ominous shadows, is by David Hersey. . . . “Equus” — the Latin word for horse — is as much a mystery as it is a melodrama rife with pyschosexual and religious overtones. . . . Visually, there are some stunning effects. “Equus” celebrates ritual, particularly in its portrayal of the horses . . . “Michael Kuchwara, Associated Press

“The young wizard has chosen wisely. Making his Broadway debut in Thea Sharrock’s oddly arid revival of Peter Shaffer’s “Equus,” which opened Thursday night at the Broadhurst Theater, the 19-year-old film star Daniel Radcliffe steps into a mothball-preserved, off-the-rack part and wears it like a tailor’s delight — that is, a natural fit that allows room to stretch. Would that the production around him, first presented in London, showed off Mr. Shaffer’s 1973 psychodrama as flatteringly as it does its stage-virgin star. . . . Mr. Griffiths and Mr. Radcliffe (who stops short of the all-out religious ecstasy of Peter Firth, who created his part) are delivering utterly credible and often affecting performances. And I was always thoroughly engaged by their scenes together, which generate the genuine tension of clashing minds longing to meld. . . . The problem with such well-considered acting is that it throws a clear and merciless light on the hokum of the play as a whole. . . . I never felt a ripple of vicarious passion . . . As Alan’s child-warping parents, Carolyn McCormick and T. Ryder Smith offer broad emotions without the refining detail of individual character. Anna Camp is appealingly natural . . . But Kate Mulgrew . . .“ Ben Brantley, the New York Times

“Radcliffe, despite limited experience in live theater, turns out to be a stage actor of extraordinary presence, generosity, and power. He’s the real thing. What’s also interesting is to see how the play itself does and does not hold up . . . with its argument that psychiatry, though it may allow people to fit more easily into society, robs them of an essential wildness. Be passionately alive or live a normal life: Choose one. In 2008, that doesn’t feel like a fresh dilemma, nor does it seem central to the social conversation in the same way it did then. Nevertheless, director Thea Sharrock and her design team – find majestic, spooky, and striking ways to embody the themes onstage. . . . the production builds a sustained emotional power. . . . Alan’s parents are played with tightly coiled emotion by Carolyn McCormick and T. Ryder Smith . . . It’s Alan’s scenes with the horse, stranger and more hauntingly erotic, that rightfully linger in the mind. . . . “Equus” doesn’t really make sense, any more than the nonsense language that Alan makes up to talk about his horses. Watching him embrace that steamy creature, though, we know exactly what it means.” Louise Kennedy, Boston Globe

“This is Radcliffe’s first serious stage portrayal, and though his contribution won’t blow you away, it does get a basic job done. . . . The doctor is played, fortunately, by the gifted Richard Griffiths . . . Thus in this erratic revival of “Equus” there is a core of leading-player technical proficiency. Even though the play itself comes across now as a solemn, stately affair, involving a therapeutic “mystery” so stuffed with transparent clues that a freshman psychology major could crack it. . . . The show’s balance of star power shifts to the younger character. It’s not at all clear that this is good for the story, for “Equus” is perhaps more about an older man’s yearning for some kind of spiritual renewal than it is about the roots of a boy’s pathological behavior. . . . Director Thea Sharrock goes in mostly for a nostalgic embrace of the original’s highly theatrical staging . . . Some of the acting is impressive . . . A few other performances are seriously misdirected . . . As Alan’s parents, Carolyn McCormick and T. Ryder Smith turn in rather gray portrayals. . . . The proceedings remain remarkably unimpassioned . . .” Peter Marks, Washington Post

“The good and bad news about the new Broadway revival of Equus with Daniel Radcliffe is that the actor is aging a lot more gracefully than the play. Shaffer’s account of a 17-year-old who blinds six horses in a fit of sexual and spiritual agony and the psychiatrist who tends to his tortured soul is undeniably seductive in its use of words and imagery. But it’s riddled with clichés and specious suggestions about the human mind and spirit. . . . It’s a credit to Radcliffe, his estimable co-star Richard Griffiths and director Thea Sharrock that this Equus transcends the more frustrating elements of the text. . . . As Alan’s dad, T. Ryder Smith delivers a more grounded, accessible performance, as does the fetching Anna Camp, playing a young woman who tries to lure Alan into adulthood. But the most sensually evocative moments involve the horses . . . they are hypnotic, haunting figures, more beautiful and ominous than any phrase in the script. If Equus doesn’t share their unmannered grandeur, at least this staging pays homage to it.’ Elyse Gardner, USAToday

“Doesn’t manage to bring sufficient life to what is a now-dated and often-plodding psychological drama. . . . For most theatregoers, the immediate subject of interest for this production will be how Daniel Radcliffe fares in his theatrical debut. The answer is, well enough. . . . the young actor displays a confident physical presence . . . and intensity. But he doesn’t quite manage to fully plumb the disturbed depths of the character . . . Griffiths is deeply disappointing . . . failing to convey Dysart’s underlying despair about his own emotionally barren life that causes him to envy his patient for his passion. Director Thea Sharrock’s staging is similarly listless . . . The supporting players, including Carolyn McCormick and T. Ryder Smith as Alan’s repressed parents and Anna Camp as the young woman whose ill-fated seduction sets the horrifying events in motion, are quite good. But the play itself, trafficking in ’70s-era, R.D. Laing-inspired ideas about psychotherapy, feels even more dated than it need be in this less-than-compelling rendition.” Frank Scheck, Reuters/Hollywood Reporter

“Limply staged by Thea Sharrock . . . The lurid, once-shocking material is showing its age . . . And the uneven cast drags the pace down too often. Griffiths, so sparky and impish in The History Boys, opts for a resigned melancholia that saps Dysart’s rage and turns everything into a sheepish shrug. Radcliffe certainly went bold for his stage debut (insanity! nudity!) and he’s an energetic presence, but his Alan is flat and shallow. Word of advice to movie stars clattering across our stages: Learn to trot before trying to gallop.” David Cote, Time Out NY

Offstage

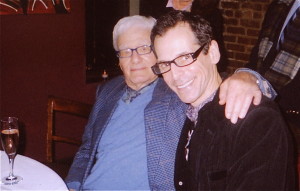

Above: right, with Anna Camp and Kate Mulgrew; left, with Peter Shaffer.

Full reviews

New York Times, Ben Brantley – In the darkness of a stable. The young wizard has chosen wisely. Making his Broadway debut in Thea Sharrock’s oddly arid revival of Peter Shaffer’s “Equus,” which opened Thursday night at the Broadhurst Theater, the 19-year-old film star Daniel Radcliffe steps into a mothball-preserved, off-the-rack part and wears it like a tailor’s delight — that is, a natural fit that allows room to stretch. Would that the production around him, first presented in London, showed off Mr. Shaffer’s 1973 psychodrama as flatteringly as it does its stage-virgin star.

Stretching without tearing is presumably what Mr. Radcliffe, who has spent most of his adolescence playing the schoolboy sorcerer in the globally popular Harry Potter movies, had in mind when he took on the role of Alan Strang, a 17-year-old suburban stableboy who commits grotesque and seemingly inexplicable crimes against horses.

For Alan Strang is, in a sense, a tidy inversion of Harry Potter. Both come of age in a menacing, magical world where the prospect of being devoured by darkness is always imminent. The difference is that for Harry that world is outside of him; Alan’s is of his own creation.

Like many beloved film actors Mr. Radcliffe has an air of heightened ordinariness, of the everyday lad who snags your attention with an extra, possibly dangerous gleam of intensity. That extra dimension has always been concentrated in Mr. Radcliffe’s Alsatian-blue gaze, very handy for glaring down otherworldly ghouls if you’re Harry Potter. Or if you’re Alan Strang, for blocking and enticing frightened grown-ups who both do and do not want to understand why you act as you do.

I had forgotten just how much is made of Alan’s eyes in “Equus,” which became a sensational upper-middlebrow hit when it opened in London and later on Broadway more than three decades ago. His stare is variously described as accusing, demanding and, in the case of a comely lass who just wants to bed him, amazing. Fortunately it projects as big from the stage as it does in cinematic close-up, as does Mr. Radcliffe’s compact, centered presence (which he retains even stark, raving naked). In any case, it’s the look of someone who sees and feels more deeply than ordinary folk. Such depth is to be envied — isn’t it? — even if it prohibits its possessors from fully belonging to human society.

That’s the conundrum at the heart of “Equus” and in most of Mr. Shaffer’s plays, particularly his “Amadeus,” in which an 18th-century wild child named Mozart has the lesser composer Salieri grinding his teeth in homicidal jealousy. In “Equus,” the envying is done by Martin Dysart (the superb Richard Griffiths), the psychiatrist asked to oversee Alan’s treatment after the boy blinds six horses one night in the stables where he works.

Dysart acknowledges that what Alan has done is unspeakable. But as he shines a light into the recesses of the boy’s mind he sees the landscape of a self-made, chthonic religion in which the horse is God. For Dysart, a man in a sterile marriage who has measured out his life in patients’ files and annual holidays in Greece, Alan’s inner existence has the mythic grandeur of Homer’s Olympus.

Mr. Griffiths, who won a Tony as the inspiring, student-fondling teacher in Alan Bennett’s “History Boys,” plays Dysart with less masochistic swagger than I’ve ever seen. It was pretty hard to buy the kvetching of the sonorously suffering Richard Burton, who played the part in the 1977 film (and briefly on Broadway), about being so damned meek and ordinary.

On the other hand, Mr. Griffiths does banality beautifully, presenting Dysart in the early scenes as someone who has smoothed out every utterance to the same level of flat, professional detachment, lightly spiced with witty self-deprecation. He resists the temptation to play hotdog surfer, riding the purple waves of Mr. Shaffer’s symbol-saturated monologues. He builds Dysart’s character with care, so when the eruptions of naked doubt, self-contempt and sorrow finally break out, he’s earned them.

But while I can’t imagine another actor making more sense of Dysart, I’m not sure that the character — or for that matter, the play — benefits from such scrupulous treatment. Mr. Griffiths and Mr. Radcliffe (who stops short of the all-out religious ecstasy of Peter Firth, who created his part) are delivering utterly credible and often affecting performances. And I was always thoroughly engaged by their scenes together, which generate the genuine tension of clashing minds longing to meld.

The problem with such well-considered acting is that it throws a clear and merciless light on the hokum of the play as a whole. “Equus” was written in the shadow of the then voguish theories of R. D. Laing, which championed the creative beauty within madness while fixing blame on the repressiveness of the conventional family.

We were just out of the 1960s when “Equus” arrived, and this creed of communing with one’s inner madman had more appeal than it does today, when people are doing their best to hold themselves together as familiar social structures threaten collapse. To buy into the innate worth of Alan’s raging fantasies, we more than ever have to feel viscerally the exhilaration he feels.

Yet for all the inventive stagecraft of John Napier, the designer of this and the first production, and Ms. Sharrock (who stays close to the spirit of John Dexter’s original direction) — for all the prancing horse-masked dancers on the revolving stage with its Stonehenge-like blocks — I never felt a ripple of vicarious passion. The careful realism of Mr. Griffiths’s and Mr. Radcliffe’s performances makes you appraise their characters with a newly sober eye.

This means that the homoerotic aspect of Alan’s equine dreams becomes excruciatingly blatant, a garden-variety sexual identity crisis dressed up for a night at the races. You can hear every metaphor falling into place with an amplified click, just as the psychological clues to the detective-story aspect of the play seem to be announced with the equivalent of a suddenly illuminated light bulb.

It doesn’t help that Ms. Sharrock has the supporting cast members turning directly to the audience to make such announcements (things along the lines of, “Well, now that you mention it, he did keep this strange picture above his bed.”). These performances are infected with the let’s-out-British-the-British strain that often happens to New York actors mixed with English actors in English plays.

Such affectations would matter less if everyone were pitched at the same stylistic tone. But as Alan’s child-warping parents, Carolyn McCormick and T. Ryder Smith offer broad emotions without the refining detail of individual character. Anna Camp is appealingly natural as the young woman who unwittingly leads Alan to his acts of destruction.

But Kate Mulgrew, as the magistrate who is Dysart’s confidante, is alternately as plummy and mannered as a society matron in a Maugham drawing-room comedy and as portentous as a sinister housekeeper in a creaky-old-house chiller.

Ms. Mulgrew, for the record, was the only cast member awarded with exit applause before the final curtain when I saw the show (this after a particularly flamboyant declaration to Dysart). Personally, I winced whenever she opened her mouth, but I think the audience was hungry for the sort of campy grandeur she provided.

There’s no question that “Equus” has dated, particularly in its presentation of psychiatric investigations (something Mr. Shaffer humbly admits in a program note). But taking it too seriously may not be the best way to serve it in revival. This version had no crackling artificial fire to match the annoying smoke that kept rising through the stage floor. And as much as I admired the sensitivity and intelligence of Mr. Griffiths’s and Mr. Radcliffe’s performances, this revival might have been better off if everyone had just gone for the Gothic.

Reuters/Hollywood Reporter, Frank Scheck – Equus features young star but dated premise. Considering that its attractions include a totally naked Harry Potter and the first New York stage appearance by Richard Griffiths since his Tony-winning turn in “The History Boys,” there’s no doubt that “Equus” will be a Broadway box-office bonanza.

Unfortunately, this revival of Peter Shaffer’s landmark 1973 play doesn’t manage to bring sufficient life to what is a now-dated and often-plodding psychological drama.

For most theatregoers, the immediate subject of interest for this production — which has been imported after a hit London run — will be how Daniel Radcliffe fares in his theatrical debut. The answer is, well enough. Playing Alan Strang, the tormented 17-year-old who commits the horrific crime of blinding six horses, the young actor displays a confident physical presence — all too necessary, considering the length of his Act 2 nude scene — and intensity. But he doesn’t quite manage to fully plumb the disturbed depths of the character, as Peter Firth did so brilliantly in the original production and 1977 film version.

As Martin Dysart, the provincial psychiatrist who reluctantly agrees to treat the young man at the urging of a sympathetic magistrate (Kate Mulgrew), Griffiths is deeply disappointing. The role has been a vehicle for triumphant turns from actors ranging from Anthony Hopkins to Richard Burton. But Griffiths, whose rotundity robs the proceedings of its homoerotic undertones, barely seems to register, failing to convey Dysart’s underlying despair about his own emotionally barren life that causes him to envy his patient for his passion.

Director Thea Sharrock’s staging is similarly listless, resulting in an evening that feels far longer than its two hour, 40-minute running time. She was smart enough to recruit the services of original designer John Napier, whose wooden amphitheatre-style setting and giant metal heads for the six strapping actors playing Alan’s equine victims are again effective. But the lack of dramatic pacing proves deadly, and the overwrought staging of the blinding scene, which resembles a Martha Graham ballet gone wild, is more laughable than frightening.

The supporting players, including Carolyn McCormick and T. Ryder Smith as Alan’s repressed parents and Anna Camp as the young woman whose ill-fated seduction sets the horrifying events in motion, are quite good. But the play itself, trafficking in ’70s-era, R.D. Laing-inspired ideas about psychotherapy, feels even more dated than it need be in this less-than-compelling rendition.

USA Today, Elysa Gardner – The good and bad news about the new Broadway revival of Equus (* * * out of four) with Daniel Radcliffe is that the actor is aging a lot more gracefully than the play.

In this London-based production, which opened Thursday at the Broadhurst Theatre, the Harry Potter star puts to rest any arguments that his appeal should be limited to moony adolescents and maudlin grown-ups. If only the same could be said for Peter Shaffer’s 35-year-old drama.

Shaffer’s account of a 17-year-old who blinds six horses in a fit of sexual and spiritual agony and the psychiatrist who tends to his tortured soul is undeniably seductive in its use of words and imagery. But it’s riddled with clichés and specious suggestions about the human mind and spirit.

Alan Strang is presented as a victim of both repressive forces and his own acute emotions and probing imagination. In treating him, Dr. Martin Dysart worries that he’ll “stamp out” these qualities and make “a ghost” of the boy.

“Passion, you see, can be destroyed by a doctor; it cannot be created,” Dysart tells us. It’s a catchy line, but isn’t a therapist’s job to help patients better understand and channel their passions, however brilliant or disturbed?

It’s a credit to Radcliffe, his estimable co-star Richard Griffiths and director Thea Sharrock that this Equus transcends the more frustrating elements of the text. In less able hands, Dysart and Alan might be written off as another gifted but troubled shrink and his gifted but troubled charge, but Griffiths and Radcliffe give them rich, real inner lives.

The younger actor evinces Alan’s shield of precocity and hostility, then movingly reveals the tender wounds beneath it. Griffiths’ stringent Dysart defies the sentimentality woven into the heavier passages, enhancing the production’s authority and dignity.

Kate Mulgrew puts a stentorian spin on Hesther Saloman, the magistrate who brings Alan to Dysart’s attention, and Carolyn McCormick has a few near-hysterical moments as the boy’s devout, distraught mother. As Alan’s dad, T. Ryder Smith delivers a more grounded, accessible performance, as does the fetching Anna Camp, playing a young woman who tries to lure Alan into adulthood.

But the most sensually evocative moments involve the horses, played by a group of fittingly studly men led by Lorenzo Pisoni as Alan’s favorite, Nugget. Sporting leather-and-aluminum helmets, mimicking equine elegance via Fin Walker’s robust choreography, they are hypnotic, haunting figures, more beautiful and ominous than any phrase in the script.

If Equus doesn’t share their unmannered grandeur, at least this staging pays homage to it.

Bloomberg News, John Simon – Some plays read well but play poorly; “Equus,” specious as literature, is nevertheless dazzling theater. Now Peter Shaffer’s 1973 drama rides again on Broadway, in a production starring Daniel Radcliffe, filmdom’s Harry Potter, and Richard Griffiths, aka Uncle Vernon and star of “The History Boys.” It is a gripping spectacle but not a substantial one.

You may recall from previous productions, or the movie starring Richard Burton, the story of child psychiatrist Martin Dysart, asked to treat a troubled 17-year-old stable boy, Alan Strang, who has, for unknown reasons, blinded six horses in his care. Can Dysart, while wrestling with his own midlife crises, unearth the defiant boy’s secret and make him “normal”? And what’s so great about normal anyway?

One has to admire supreme theatrical cunning. Shaffer serves up a boy with assorted religious, sexual and psychological problems who worships horses and a horse god, Equus; a shrink who, his marital sex life dead, pores over pictures of naked Greek gods and deplores his own lack of passion; a boy’s father, an atheist frequenting the local porno house, and a mother who is a Bible-thumping Christian; and a scene with full frontal male and female nudity.

Bravura Effects: Add to this a sextet of athletic young men in striking equine masks and hooves, and light-up eyes, prancing about with especial drama in a balletic blinding scene; plus various other bravura effects of scenic, costume and lighting design (despite the rather Spartan settings themselves, signified mostly by a handful of movable rectangular black boxes).

There is something here for everybody — except the hapless few who expect honest playwriting.

With blinding cleverness, Shaffer has devised a theatrical Rorschach test, onto which each of us may project his own desires. There is melodrama enough for tabloid devotees, pinchbeck mysticism and pseudo-poetry to make Kahlil Gibran’s “Prophet” envious, and tendentious philosophizing to lift the hearts of anyone who has it in for psychotherapy and cherishes his neuroses.

This said, we get a production that is a sight for sore eyes and susceptible ears. Radcliffe’s Alan is compelling proof that there is life after wizardry: he quells and quakes, adores horses and provokes humans with equal proficiency and looks great disrobed. Ditto for Anna Camp, fine actress and pert looker, who plays Jill, the girl who tries to seduce Alan, with disastrous results.

Bewildered Parents: No less notable is the supporting cast, headed by Carolyn McCormick and T. Ryder Smith as the bewildered parents, Kate Mulgrew as a compassionate magistrate and Lorenzo Pisoni, adept as both horseman and horse.

And then there is the tormented psychiatrist and narrator of Griffiths, an actor of vowels as pear-shaped as his frame. He gives a cogent but slightly overemphatic performance, somewhat less touching than that of his best predecessors.

No complaints, however, about John Napier’s chaste yet evocative set and with-it costumes, David Hersey’s mesmerizing lighting, Gregory Clarke’s spooky sounds, and Fin Walker’s equine choreography. Thea Sharrock’s direction pulls it all together with exemplary empathy and electricity.

This, though, is finally a dated work, harking back to all those plays and movies of the ’60s and ’70s in which loonies were ultimately, if not clinically sane, in many ways superior to those supposedly sane ones who analyzed and hospitalized them. So up with passion, however misguided, and down with normality, however highly prized.

New York Newsday, Linda Winer – Well, he’s the real thing. He may be Harry Potter to the rest of the world. But for almost three hours on Broadway last night, Daniel Radcliffe, 19, quietly transfigured himself from adorable boy wizard to horrifically unstable teen stable boy – and, in the process, bravely established himself as a smart, intense, wildly serious stage talent.

Radcliffe, who has been growing up in public since 12, made his justly celebrated stage debut last season in London with Richard Griffiths in this revival of “Equus,” Broadway’s first since Peter Shaffer’s psychosexual thriller won the Tony Award in 1975.

The actor, tiny but a commanding feral presence, manages to be both extraordinarily lucid and mysterious as Alan Strang, the alienated provincial English boy who literally worships horses but blinds six of them in an explosion of psychosexual religiosity. Radcliffe, despite the visceral physicality of the role, appears supremely comfortable in his own skin – and, yes, kids, thanks to the nude scene, we get to see all of it.

“Equus” always was pretty much of a crock – pseudo-serious humanity-on-trial hokum dressed up in mythic profundity.

But it remains excellent hokum, spectacularly theatrical, stylized with dangerously gorgeous horses imagined through male dancers with metal lattice horse heads and scary-high metal platform hoofs. Thea Sharrock’s lean and effective production overuses the fog machine but wisely retains John Napier’s original costumes and set, a silver circular amphitheater that suggests everything from hospital clinic to stable to the beach where Alan first experienced ecstasy on horseback.

Griffiths – acclaimed here in “The History Boys” and globally viewed with alarm as Harry’s mean Uncle Vernon – is not the self-doubting but dashing child psychiatrist variously played on Broadway by Anthony Hopkins, Anthony Perkins and Richard Burton (seen in the awful 1977 movie). Rather, this Dysart is a disheveled mountain of a man in shirttails, a lived-in workaholic whose experience, confessed to us, really does appear to have thrown him physically off his form.

Shaffer’s central question involves normalcy. Does “curing” Alan remove his high notes, the myth and passion that Dysart misses in his own life? Kate Mulgrew does what she can as the magistrate, less a character than a plot device. Anna Camp – who, incidentally, also gets naked – has a bold naturalness as the gutsy stable girl, while Carolyn McCormick and T. Ryder Smith find the idiosyncratic truths in Alan’s conflicted parents.

Finally, there are those horses, led by Lorenzo Pisoni as Alan’s equine godhead, and Radcliffe, who proves to be a magical force – even when the demons are internal.

Variety, Marilyn Stasio – Stunt casting in theater can do a disservice to playwrights, with famous faces often monopolizing attention while devaluing the merits of the work itself. But in his impressive debut in a major stage role, as the disturbed adolescent in “Equus,” Daniel Radcliffe significantly helps overcome the fact that Peter Shaffer’s 1975 Tony winner doesn’t entirely hold up. The play is an astute career move for the “Harry Potter” frontman as he confidently navigates the transition from child stardom to adult roles — and Radcliffe’s performance provides “Equus” with a raw emotional nerve center that renders secondary any concerns about its wonky and over-explanatory psychology.

Premiered at the National Theater in London in 1973 and transferred to Broadway the following year for a celebrated three-year run, “Equus” has always been less notable as a psychological investigation than as a vehicle for two mesmerizing lead performances backed by striking stagecraft. Taking her cue from John Dexter’s stark original staging and retaining the crucial collaboration of that production’s designer, John Napier, director Thea Sharrock correctly understands the play’s chief asset is its blazing theatricality.

Sharrock leans a little too forcefully on the atmospherics at times, cranking up the smoke machine and ominous ambient music with a heavy hand. But the production is visually dazzling, making assured use of David Hersey’s penetrating lighting and Napier’s stylized set, with its imposing coliseum of stable doors surrounding a revolving central platform with four movable rectangular blocks. Leaning forward to look down from above, the two elevated rows of onstage audience members heighten the drama’s sense of claustrophobic, inescapable scrutiny.

Constructed by Shaffer around sketchy information regarding a horrific crime that took place in regional England, the mystery thriller is basically a series of taut encounters between the perpetrator, Alan Strang (Radcliffe), a stable boy who inexplicably blinded six horses with a metal spike, and Martin Dysart (Richard Griffiths), the psychiatrist assigned by the state to discover his reasons. As Dysart coaxes his recalcitrant subject, via hypnosis and abreaction, to revisit the roots of his disturbance and the harrowing events of the crime, the shrink comes to regard the boy’s violent passion with something approaching envy.

With his effortless naturalism and mental agility, balancing clinical detachment, curiosity and concern, Griffiths makes Dysart’s self-discovery as painful and unsettling as Alan’s. Stuck in a lifeless, childless marriage of “antiseptic proficiency” and sustained only by his fascination with Greek mythology, Dysart is confronted during the course of his inquiry by his hunger to be (or be with) someone instinctive, passionate, capable of being transported by worship.

Alan’s rapturous psychosexual deification of the animal that has captured his imagination since childhood forces Dysart to acknowledge the emptiness of his own sad suburban life. As he steers the boy toward recovery, he begins to wonder, in the monologues woven throughout the play, if by restoring Alan to “a normal life” he’s not merely quenching his spirit.

Thanks in large part to the integrity of Griffiths’ performance, this dubious consideration remains affecting. It’s in the particulars of Alan’s case and Dysart’s treatment of him that things get shaky.

Shaffer’s text is grounded deep in the 1960s-’70s psychology of R.D. Laing, with its notions about the transformative aspects of mental illness, adding a heavy dollop of Freud and a hint of Marxist philosophy concerning the denial of individual freedom. But given that most audiences, three decades on, are better-versed in pop psychology and mental disorders, all this comes across as elementary, outmoded or even professionally inept.

The play has frequently been interpreted as a metaphor for the homosexual repression of Alan, Dysart or both. That suggestion becomes bluntly manifest here the moment strapping Lorenzo Pisoni rides on as the young horseman that transfixed the 6-year-old Alan in an indelible episode on a beach. While the boy’s fixation is with the animal — from its sweaty flanks to the cream dripping from its chained mouth (seriously) — the presentation of the horseman as a Ralph Lauren gay porn fantasy, with muscles packed into skintight jodhpurs and polo shirt, will have even the most amateur shrinks muttering to themselves about transference of desire.

Wearing the arresting raised metal hooves and steel-cage equine headgear of the six actor-dancers that provide the production’s stunning horse imagery, Pisoni also plays Nugget, the chief object of Alan’s obsession at the stable where he works. The scenes of quasi-religious ecstasy in which Alan is hoisted up on horseback for the first time, the intensely sexual release of his furtive naked night rides and, finally, the terrified raptus that follows his abortive date with stable co-worker Jill (Anna Camp) all retain the power to shock and disturb as “Equus” did in the ’70s.

But Dysart’s failure to approach, even obliquely, the likely cause of Alan’s torment while forcing him to relive the trauma now makes the drama seem somewhat specious. And the characters who contribute to shape the boy’s psychosis and push him over the edge — stern, judgmental father (T. Ryder Smith); suffocating religious mother (Carolyn McCormack); flirtatious would-be girlfriend (Camp) — are all too thinly sketched to provide texture.

Likewise the well-meaning magistrate who delivers Alan to Dysart is a role that serves merely to punctuate the shrink’s monologues, though it’s given strangely overwrought handling by Kate Mulgrew, bringing her roundest BBC vowels.

Shaffer’s main accomplishment is his skill at sustaining the mystery despite the play’s psychological transparency. But it’s a credit in particular to Radcliffe’s moving work — and to his nuanced chemistry with Griffiths — that Alan’s struggle constitutes a cogent drama, even while much of the surrounding reasoning is unsound. His Alan is antagonistic and not easily intimidated yet desperately vulnerable and alone, contradictions deftly played against Griffiths’ seeming nonchalance and increasingly troubled self-reflection.

London critics complained during the revival’s West End run that Radcliffe lacked vocal control, but time in the role and an extra year-and-a-half of maturity may have helped. His delivery here is as confident and compelling as his febrile physicality — whether fully clothed and wary or naked and defenseless.

NY Daily News, Joe Dziemianowicz – Let’s get right to it – Daniel Radcliffe, the marquee man-boy and the reason “Equus” has trotted back to Broadway.

Yes, he’s terrific and gives a passionate performance as Alan Strang, the 17-year-old stable hand who worships – and blinds – six horses. Yes, he’s nude in a scene, but not gratuitously. And yes, he’s (at least partially) in good company in the revival of Peter Shaffer’s play, which intrigues but shows its age.

Richard Griffiths, a Tony winner for “The History Boys” and one of Radcliffe’s “Harry Potter” co-stars, portrays Martin Dysart, the shrink in search of a reason for Alan’s sexual and religious fixation on horses (cue childhood trauma, problematic parents and hypnosis) and his violent act.

Griffiths is convincing as a weary psychiatrist who’s emotionally closed down confronting a boy who feels too much. Both men are changed by the experience, not altogether credibly. That Dysart would curse himself for curing Alan, effectively robbing him of his equine obsession, seems far-fetched in light of the severity of the crime.

Both actors reprise roles they played last year in London, and their scenes together demand your attention, unlike the doc’s lengthy monologues. They anchor Thea Sharrock’s otherwise uneven and gimmicky production. There’s more dry-ice mist than in a monster movie, and as blocks are forever being shoved around the stage, it’s as if the set was inspired by a sectional sofa.

As in the 1974 original, the horses are men in brown wearing masks and high-rise steel boots created by John Napier. While wonderfully theatrical, they’re distracting. The buff boys pose mechanically, hitting marks like runway models. It doesn’t help that their eyes glow, sci-fi-style.

Supporting roles are a mixed lot. Anna Camp brings natural vivacity as Jill, the young stable girl whose roll in the hay with Alan brings disaster. T. Ryder Smith has the right stoniness as Alan’s reserved father. But Kate Mulgrew, as a pushy magistrate, and Carolyn McCormick, who plays Alan’s devout mother, seem to be in a contest for overacting. A growling Mulgrew gets the rose wreath by a nose.

The play’s most over-the-top moment comes when the horses go into a frenzy, a scene that could chill but ends up just outlandish. Fin Walker gets credit for movement. But as the six horse-men flounced and flailed, it recalled a Mia Michaels’ routine on “So You Think You Can Dance.”

In the end, Sharrock dispenses with trickery and leaves us with an image of Dysart crowned by six floating horse heads that gleam in David Hersey’s pure white light. It’s haunting and powerful and, finally, free of mist and blazing orbs.

Time Out NY, David Cote – I doubt that teen fans of the Harry Potter franchise are equally avid for the writings of Nietzsche and Jung, but after seeing Daniel Radcliffe in Equus, they might be. Peter Shaffer’s 1973 equinocentric psychodrama never mentions those German thinkers, but it is suffused with dream symbolism and the clash of Christian and pagan sexual mores. Such themes are more or less explicitly raised by Dysart (Griffiths), the deeply conflicted psychiatrist who guides us through his radical treatment of Alan Strang (Radcliffe), a young man who has blinded six horses with a spike.

Sorry, spoiler-haters: Alan’s trouble is basically sexual. But you probably guessed that from the relentless publicity campaign placing a buck-naked Radcliffe in provocative positions with an unimpressed-looking horse. In the actual show, limply staged by Thea Sharrock, the steeds are studly actors in skintight outfits and metal-mesh horse heads. Set and costume designer John Napier, who handled the original production, basically revisits his ’70s sketches, which is a shame. A fresh U.K. company such as Improbable or Complicite could have done theatrical wonders with the text.

That lurid, once-shocking material is showing its age, even if it’s not quite time for the glue factory. And the uneven cast drags the pace down too often. Griffiths, so sparky and impish in The History Boys, opts for a resigned melancholia that saps Dysart’s rage and turns everything into a sheepish shrug. Radcliffe certainly went bold for his stage debut (insanity! nudity!) and he’s an energetic presence, but his Alan is flat and shallow. Word of advice to movie stars clattering across our stages: Learn to trot before trying to gallop.

Village Voice, Michael Feingold – The cherries that grew in Chekhov’s Cherry Orchard, the old butler Firs tells the younger generation, were formerly made into jam, but over the years, the recipe somehow got lost. I often think old plays have the same problem: The tasty condiment they once provided onstage now often comes out savorless. The recipe’s disappeared, and nobody knows how to retrieve it. Strict historical authenticity gives you pedantic staleness; total freedom tends to produce a weird-tasting contemporary ick; steering moderately between those extremes results in something bland and viscous, not at all the tangy-sweet cherry jam you were dreaming of. That dish is only available in your imagination or your memory.

Peter Shaffer’s 1974 play Equus poses a particular challenge in revival because it was already a mixed dish of debatable quality. John Dexter’s original production—cold, sharp, and riveting—had a lot to do with its initial success. The wire-sculpture heads that John Napier designed for the play’s “horses” inspired many jokes back then: I never dreamed I’d miss them till I saw Thea Sharrock’s new production, also designed by Napier. The translucent, quasi-realistic sculpted horse heads here suggest artsy samples of Steuben glassware, perfectly matching the rest of the design, which has the tony austerity of a decorator’s showroom.

Shaffer’s drama mixes a savory piece of psychiatric melodrama with some suspicious-smelling reflections on its meaning. Alan Strang (Daniel Radcliffe), the disturbed teenage son of a deeply riven marriage, has committed a hideous, inexplicable act: blinding six horses. Yet horses are apparently all he loves. A sympathetic judge (Kate Mulgrew) assigns a shrink, Martin Dysart (Richard Griffiths), to discover what drove him to it. What Dysart learns, played out gradually in flashback as he steadily induces the closed-off Alan to lower his guard, constitutes the melodrama, many scenes of which are powerfully effective. But as Alan’s revelations deepen, Dysart—a burnt-out case in both his profession and his marriage—becomes increasingly envious, causing a lot of showy soliloquies about how violently disturbed lunatics are emotionally superior to ordinary, inhibited people whose lives have gone dead.

The essential hogwash (not to be confused with Hogwarts) of this glib comparison gets further muddling from the play’s dodgy treatment of key matters like sanity and legality. Dysart keeps asserting that he will “cure” Alan and return him to “normal” life, which he ultimately views as a tragic loss. But psychotherapy doesn’t “cure” people, except on Broadway (was Shaffer remembering Kim Stanley in A Far Country?), and we never learn precisely what the judge has appointed Dysart to do: gauge Alan’s sanity, estimate whether his condition makes him a danger to society, or take him on permanently as a patient. The possible penalties Alan faces for his crime also remain nebulous, but a humdrum suburban existence probably isn’t one of them; you don’t get that in Dartmoor.

The hogwash taints Sharrock’s production particularly because Griffiths, a capable actor hopelessly miscast, never suggests a man whose inner discontent is constantly gnawing at him. On the contrary: Griffiths’s placidly adipose Santa Claus of a shrink seems to have done far too much gnawing himself. Sharrock’s weak hand at shaping performances is confirmed by the supporting cast, no two of whom appear to be in the same play. Only Carolyn McCormick as Alan’s mother and Lorenzo Pisoni as his favorite horse offer the crisp, forceful clarity that Shaffer’s script demands.

And only Radcliffe supplies the vital ingredient of which Equus, unhappily, requires two full portions: the commanding stage presence of a star. His quiet, recalcitrant Alan, eschewing the feral sullenness that made Peter Firth, in the original, excitingly scary to watch, builds ultimately to a creepier height of near-total dislocation. Hewing tautly to the play’s dramatic line, Radcliffe makes the cornball “atmospherics” (stage fog, throbbing music) with which Sharrock surrounds him seem all the more ludicrous.

NY1, Roma Torre – When my mother took me to see the original production of “Equus,” it stayed with me for years. I was much too young to judge its merits, but I see now why the play had such an impact. It really is a mesmerizing work that reaches deep into the psyche.

Designed as a suspense yarn, it makes the most of theatrical conventions to question some of our most basic beliefs about sanity, religion and childhood influences.

The 35-year-old play certainly holds up today and thanks to a fine British revival, Peter Schaffer’s remarkable drama remains essential Broadway viewing. Staged by Thea Sharrock, “Equus” remains a riveting synthesis of stage craft and theatrical vision.

“Harry Potter” star Daniel Radcliffe, I’m happy to report, is not merely the stunt casting gimmick you might have expected. Making his stage debut, the 19-year-old movie star works some fine acting magic in the central role of Alan Strang, a seemingly gentle stable boy who viciously blinds six horses in his care.

Radcliffe and Richard Griffiths, in the role of psychiatrist Martin Dysart, have a keen rapport on stage that likely stems from their long working relationship in the “Harry Potter” films.

“Equus” is essentially a “whydunnit,” with Dysart methodically unraveling the facts in the case. Some minor changes in the production include a bit of tweaking in the script to give it a more contemporary feel, along with Griffith’s dressed-down approach to what was a far more formal interpretation in the original.

Designer John Napier returns with a set quite similar to his original featuring those stunning giant metal horse heads worn by sleekly choreographed young men with nothing more suggestive than platform shoes resembling hooves. The stylized concept is extremely effective for a play with such universal appeal.

The performances range from the stellar two principal roles to some disappointing acting. The usually impeccable Kate Mulgrew goes way over the top in a frantic display that suggests her magistrate character needs some head shrinking herself.

Yet the play’s virtues remain intact. As the good doctor measures his mundane existence against the impassioned impulses of his disturbed young patient, we find there’s a little Dysart and Strang in all of us.

It’s hard to match the exhilaration that greeted the original production. But this powerful revival still manages to stir a level of passion that only live theater can evoke.

Huffington Post, Fern Seigel – The story is dramatic and disturbing – a child psychiatrist tries to discover why a 17-year-old British boy blinded six horses. Based on a true incident, Equus explores the impulses of rational and irrational man. Healthy passions are pitted against twisted ones. But the power of Peter Shaffer’s play, a revival of his 1973 success, is in the dark undercurrents of desire gone wrong. Both Richard Griffiths, as the worn-out psychiatrist, and Daniel Radcliffe, best-known as Harry Potter, give strong performances. Radcliffe proves himself a compelling dramatic stage actor, capable of handling difficult material with care.

Now at the Broadhurst Theater, Equus delves into the boy’s psyche via the usual route: his parents. His mother (Carolyn McCormick) is a schoolteacher and religious Christian. Her love of Jesus – and his suffering – is transferred to her son, who embraces its more gruesome aspects. It is pain, not redemption, the boy craves.

When his atheist father (ably played by T. Ryder Smith), becomes horrified by his son’s fervor, he replaces the provocative photo of the crucifixion, which Alan fixates on, with a portrait of a horse. Once the two obsessions converge, the boy’s abject devotion is complete.

Given his equine worship, why does he commit such a horrendous crime? When the play first appeared in London, the author said he wanted to “interpret it in some entirely personal way. I had to create a mental world in which the deed could be made comprehensible.”

Has he succeeded? The psychiatrist in Equus is enamored of Greek mythology (the set is a stripped-down Greek temple) and trapped in a loveless marriage. He sees in the troubled teen what he calls the “natural instinctive,” versus what he sees in himself: a sad, contained conformity. Both suffer, in part, from the same malady: shame.

Indeed, the play is as much a slam on religious obsession and sterile domesticity as it is an exploration of primal urges. Equus is encased in a tense emotional atmosphere heightened by John Napier’s sleek set. His shiny metal horse heads, and the six actors who neatly mimic equine movements, enhance the drama. There are no easy answers here; even the final monologue is a bit glib: What price the cure? But the tensions are real, and the production riveting.

nytheatre.com, Martin Denton – I came to this new Broadway production of Equus having never seen the play before (nor the film starring Richard Burton). So its very particular surprises were all brand new to me, which is perhaps the only way to fully appreciate it. Because Equus is, above all else, a mystery story—a highly theatricalized one, to be sure; and one of compelling thematic depth.

The mystery revolves around a young man named Alan Strang, a 17-year-old boy living in a provincial area of southern England. Alan blinded all six horses in the stable where he works, with a metal spike; the question in Equus is not whodunit but why. Hesther Saloman, the judge before whom Alan stood when being tried for this sensational crime, has remanded him not to jail but to a psychiatric hospital, where her friend Dr. Martin Dysart will attempt to uncover the cause of Alan’s actions.

And so Dysart probes Alan’s damaged psyche, utilizing a variety of what he brazenly calls the tricks of his trade to first get through to the boy—who initially refuses to talk, answering questions only by singing TV commercial jingles—and then to uncover the truth of what led him to carry out the bizarre and outrageous mutilation of the animals he loved.

The brilliance of Peter Shaffer’s playwriting here is that Dysart, not Alan, is the protagonist of Equus. As the barriers are torn down within Alan’s mind to reveal the “solution,” we are engaged not only with discovering what it is but with the destruction that the process is wreaking on both doctor and patient. When Dysart first encounters Alan, he is a deeply disappointed man, trapped in a loveless marriage and a job that no longer satisfies him, living only for the few weeks a year when he can vacation in Greece, visiting ruins and rummaging through ancient art objects that provide his only fascination. As Alan’s treatment progresses, and as Dysart explores and meditates on it before our eyes (for the entire play is structured as a kind of confessional between him and us), he arrives at some very disturbing conclusions about the value of what he is doing. Viewed in the context of Shaffer’s later plays (Amadeus, even Lettice and Lovage), it’s clear that the struggle between conformity and eccentricity—between the routines of convention and the thrilling but dangerous insights of raw genius—are at the heart of Equus. The conclusion of the piece, which comes stunningly quick on the heels of the climactic unraveling of the mystery, is devastating and untethering.

Thea Sharrock’s production derives its power from its sense of theatrical possibility. On John Napier’s deceptively stark set, scenes from Alan’s past are replayed for us in a style that always combines naturalism with unabashed theatre magic. The horses at the stable where Alan works are played by actors wearing metal masks (representing the horse’s heads) and oversized metal platform shoes that allow them to tower over the human characters; their movements (choreographed by Fin Walker) are stylized approximations of the singular elegance of a trot, canter or gallop. Napier, with his collaborators David Hersey (lighting) and Gregory Clarke (sound), creates an astonishing world of heightened imagination that mirrors the twisted feats of invention that Alan himself achieves in the story. The realization of the play’s climax—the re-creation of Alan’s crime—is one of the most authentically horrifying moments I’ve ever seen on stage.

The two great performances in this play are, perhaps inevitably, Daniel Radcliffe’s as Alan and Lorenzo Pisoni’s as Nugget, Alan’s favored horse. Both achieve the mythic quality that their story and its context require. Excellent supporting work is delivered by Collin Baja, Tyrone A. Jackson, Spencer Liff, Adesola Oasakalumi, and Marc Spaulding, who portray the other, unnamed horses with grace and potency.

The characters outside of Alan’s world are more inconsistently rendered, however. Richard Griffiths gets Dysart’s detachment exactly right, but there’s never a moment when he pulls away from the aloofness to show us the passion that must have once lived inside this man—and perhaps may live there again—and I missed that. T. Ryder Smith has a terrific scene in the second act that lets us right into his character, Alan’s strict and repressive father; but Carolyn McCormick seems at sea as Alan’s religious fanatic of a mother. Anna Camp is fine as Jill, the young woman who works at the stables who is something of a catalyst for the pivotal events of the story. I particularly admired Kate Mulgrew’s highly theatrical turn as Hesther; she, alone among the “normal” people in the story, matches Radcliffe’s intensity note for note.

A word about the much-ballyhooed nudity in the show: both Radcliffe and Camp appear fully naked for an extensive period in Act Two, mostly in dim light and almost always positioned so that a kind of modesty is maintained. But what follows these moments is potentially pretty upsetting; a certain level of maturity really is required to appreciate and process this play.

But for those equipped in mind and heart to take it in, this really is a remarkable piece of theatre. I’m not sure how well it would wear on a repeat viewing, but I am very glad to have had the chance to experience this first-rate production of a gripping, absorbing drama.

Los Angeles Times, Charles McNulty – Daniel Radcliffe’s Broadway debut has been generating most of the buzz for “Equus,” Peter Shaffer’s 1973 psychodrama about a disturbed adolescent boy who has been placed in a psychiatric hospital for blinding six horses. The presence of the “Harry Potter” star — not just in the flesh but also in the buff for one dimly lighted scene — has spurred his global army of young fans to temporarily transfer their interest from the screen to the stage (although there weren’t many in evidence at the Broadhurst Theatre on Wednesday night, but then most allowances couldn’t cover the ticket price).

Radcliffe’s choice of material makes a lot of sense on paper: The play ran for nearly three years on Broadway in the ’70s, and the character of Alan Strang is not just a psychopath — he’s a psychopath from a bourgeois background with a very un-bourgeois secret. Not to give too much away (or psychoanalyze without a license), this withdrawn kid is seeking (before his violent spree, anyway) a kind of religious ecstasy through interspecies communion.

But there’s a role in “Equus” that’s more fascinating than the one being essayed by Radcliffe. And though the character doesn’t wield a metal spike, it has attracted such intrepid talents as Anthony Hopkins and Richard Burton.

Martin Dysart, the psychiatrist trying to unearth the motive for this shocking crime, has a wandering introspective mind that isn’t afraid of profoundly questioning the social and psychological foundations of his own identity. And as played by Richard Griffiths, in a performance that confirms his virtuosic command of refined language and probing thought, the good doctor is the chief reason for catching this rather dated play.

Sitting through “Equus” today is a bit like tracing the life cycle of psychoanalysis. The drama begins with a reaffirmation of the value of listening to the pain of others, proceeds to get bogged down in the quicksand of family dysfunction and sexual neurosis, and climaxes in an extreme ritual that is partly redeemed by the playwright’s respect for everyday enigma and the power of words to illuminate scattered patches of darkness.

The episodes with Alan’s mother (Carolyn McCormick) and father (T. Ryder Smith) are as inert and reductive as the flashback moment of erotic humiliation involving a mature-for-her-years stable girl (Anna Camp) that drives the play’s protagonist to his accountable deed of animal cruelty. The actors, under the direction of Thea Sharrock, are almost heroically credible, but there’s only so much that can be done with this kind of old-fashioned psychological baggage.

Still, Dysart’s series of dialogues, not just with his patient but also with his friend and colleague Hesther Saloman (a fervent Kate Mulgrew), have an eloquence and depth of insight that shouldn’t be lightly passed over. Radcliffe’s scratchy vocal technique needs work, but he burrows into his role with an unflinching determination. And his interaction with the horses, which are brought to life by actors with a suggestive physical grace that reminds us of Shaffer’s interest in the ’60s theater of Jerzy Grotowski, Peter Brook and Joseph Chaikin, is marked by a ferocious commitment to his character’s obsession.

Unfortunately, the play can no longer conceal its flaws under an avant-garde cover. What was once stylistically daring has become less attention-grabbing through decades of post-’60s experiment. It’s the human core that monopolizes interest now, and that core has layers of faded fabric muffling it.

It’s hard to imagine a major revival of “Equus” without the celebrity pixie dust of Radcliffe, who earns a solid B in his Broadway tutorial. But Griffiths, following his bravura, Tony-winning turn in “The History Boys,” puts on another master class that should open up to his “Harry Potter” costar a whole new world of incantatory magic.

Curtain Up, Elyse Sommer – Daniel Radcliffe has now tested his acting skills on both sides of the Atlantic. As was the case in London, the big buzz was about how he would do when he took off those big Harry Potter glasses and let the audience have a closer look at those blue eyes. . .and more, intriguing still, when he removed his clothes and gave the audience a peek at him in the altogether. According to our London critic Lizzie Loveridge, Radcliffe did just fine, as did his Harry Potter colleague and Tony Award winning (for The History Boys) Richard Griffiths as his psychiatrist. Griffith too is on board at the Broadhurst, as is the London design team.

As Shaffer explains in a brief postscript added to the program notes for the original production reprinted in this much hyped import of the 2007 London revival, he long withheld permission for new large scale productions because he was concerned about changes in psychiatric practice. Rightly so. The views of R.D. Laing (a Scottish psychiatrist whose controversial theories included a belief that psychotics inside mental institutions have as much to teach the “normal” world as the other way around, no longer stir much interest among modern psychiatrists.

Actually, the phenomenal success of Equus was less about it being great play than its dazzling theatricality and Shaffer’s ability to set up a sort of battleground for two men representing opposite approaches to passion—in Amadeus the able but conventional composer Salieri sees his talent shrink next to that of the wildly unfettered Mozart; in Equus Martin Dysart realizes that his disturbed patient has turned the conflicting influence of his mother’s extreme religiosity and his father’s atheistic and phony morality into a passion more ferociously exciting than anything he has ever known.

For all that Dysart’s guiding young Strang to relive his crime and what led up to it is more than ever a lot of psychobabbling balderdash, it makes for timeless onstage razzle-dazzle that’s fully realized in Thea Sharrock’s production. While Radcliffe is now two years older than his character, it’s noticeable only in the maturity and depth of his performance.

As for the over-hyped nude scene (which is actually a double take it as it includes Anna Camp as Jill Mason, the young girl who helps him get the job in the stable), it’s subtle and very well done. But actually, the most erotic scene is when Alan embraces the horse Nugget (Lorenzo Pisoni) in the highly dramatic Act 1 finale and becomes one with his “Godslave, Faithful and True.” Griffith is forceful as ever as the psychiatrist, though I think the viewers sitting in the very dramatic looking onstage seats (like a jury at a trial or students at a university for psychology majors) are likely to catch everything he (or for that matter, anyone else) says when facing front.

The Broadway transfer has suffered no serious losses by the integration of American actors. T. Ryder Smith (long overdue for a Broadway role) is outstanding as the father, especially in the scene where he confronts his son and Jill on their one and only date at a porn movie house. Kate Mulgrew who at times seems to think she’s in a different play, as she keeps crossing her legs in the manner of a B-Movie nightclub chanteuse. Roberta Maxwell, who played Jill in the original production, was less actressy in another and intriguingly staged and cast production I saw three years ago at the Berkshire Theatre Festival.

Whatever the merits of Griffiths and Radcliffe and company, I agree with Lizzie Loveridge that the horses are the natural stars of the show. Lorenzo Pisoni is magnificent both as the Young Horseman and the horse Nugget and the current actors playing the other horses are as awesomely costumed and watchable as ever and Lizzie’s overall appraisal of this revival applies now as then.

NY Sun, Eric Grode – From Don Quixote to Forrest Gump, one fictional savant after another has carved his way (they’re almost always men) through Western culture, unfettered by the suffocating mores of society as he inspires the surrounding hordes of the “well.”

Unsurprisingly, the 1960s and early ’70s were a particularly fertile time for this reductive but nonetheless comforting thesis. The decade bracketed by the 1962 publication of Ken Kesey’s “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” and the 1973 London premiere of Peter Shaffer’s “Equus” (now receiving a starry and more than serviceable Broadway revival) saw an enormous number of similarly themed projects. The New York stage alone featured three different “Cuckoo’s Nest” adaptations, as well as the short-lived Stephen Sondheim musical “Anyone Can Whistle,” in which the inhabitants of a town’s sanitarium intermingle fruitfully with the citizenry, and one of the decade’s most popular musicals, the “Don Quixote” adaptation “Man of La Mancha.”

Unlike those other “wise fool” entries, however, “Equus” focused less on the fool’s wisdom and more on the wise man’s folly. Mr. Shaffer’s oddly compelling ode to atavism, directed here a bit too flashily by Thea Sharrock, features as its narrator not the damaged Alan Strang (Daniel Radcliffe, better known as Harry Potter) but rather Martin Dysart (Richard Griffiths), the psychiatrist to whose care he has been entrusted. The 17-year-old who works part-time at a stable in southern England has savagely blinded six horses; Dysart has been asked to find out why.

At first the drama unfolds on a typical therapy-as-procedural path, as the recalcitrant Alan gradually yields glimpses of the signposts that led to his seemingly senseless act. (It’s a fairly predictable batch of sexual confusion, zealous Christianity, and parental hypocrisy.) But Mr. Shaffer, while giving ample attention and stage pizzazz to this plot thread, then shifts his attention to Dysart, a stifled aesthete who longs to throw over his “antiseptic proficiency” for the pagan vigor of ancient Greece.

The more Dysart learns about Alan’s baroque worship of the horses — Equus is the boy’s name for “the Godslave, Faithful and True” — the more he laments his own sterile life. “That boy has created out of his own drab existence a passion more ferocious than any I have known in any second of my life,” he cries to his co-worker, Hesther (a grievously misdirected Kate Mulgrew, who approaches her supporting role like a headlining grande dame). “And let me tell you something — I envy it.”

It is ironic and a bit unfortunate, then, that Mr. Radcliffe’s performance is by far the more controlled and Mr. Griffiths’s the looser. (Both are repeating the roles they played last year in London; the rest of the cast is new.) In general, however, Mr. Radcliffe accentuates the strains of evasion and scorn common to all adolescents without slighting the deeper veins of unrest. And even though Mr. Griffiths falls back on rumpled-academic shtick here and there — with much rubbing of the eyes and scratching of the head as he ruminates — he also gives Dysart a welcome burst of energy whenever his assumptions are jostled.

The climactic shift in tone from Alan’s Dionysian reverie to Dysart’s Apollonian regret happens far too abruptly at the end of this “Equus,” a jolt for which Ms. Sharrock must assume much but not all of the blame. (It comes immediately after Mr. Radcliffe’s endlessly hyped nude scene, one that he and his costar Anna Camp handle with finesse.) While John Napier’s original stage design remains haunting — a sextet of fine dancers led by Lorenzo Pisoni eerily impersonate the horses with the aid of skeletal masks and hoof-like platform footwear, a riff on the cothurni from Dysart’s beloved ancient Greece — the staging of Alan’s passionate equine encounters relies too heavily on musty psychosexual pageantry. (Ms. Sharrock’s corny sound effects and fog machines don’t help, though.)

These scenes may be responsible for the initial success of “Equus,” and the titillation factor has a lot to do with the revival’s success, but they haven’t aged particularly well. Nor have Dysart’s self-flagellating laments at delivering “the indispensable, murderous God of Health” to his damaged young patients.

Focus instead on the scene just before Alan’s cathartic return to the stables. Both patient and doctor have tacitly agreed to enable Alan’s confession through a placebo “truth drug.” In the minute or two after he takes it, the two men — the childless doctor and the boy desperate for parental approval, each nursing his own blend of foreboding and anticipation — share a cigarette and make small talk about Greek mythology and Dysart’s unprepossessing office. Mr. Shaffer’s teeth-gnashing falls away briefly, and it’s as if Ms. Sharrock and her two stars can feel the reins slacken.

Associated Press, Liz Smith – Back in 1976, I sat through “Equus,” Peter Shaffer’s thought-provoking (and then-shocking) play about a boy who commits a horrible act — blinding six horses — and the therapist who attempts to heal him.

The boy, Alan Strang, was played by Peter Firth, who had originated the role in London and on Broadway opposite Anthony Hopkins as Dr. Martin Dysart. But when Hopkins left the play, Richard Burton stepped in. It was Burton’s first stage role in years, after a string of embarrassing films. Burton’s return should have been enough to fix audience attention to the action onstage. Alas, up in the balcony that night, arrayed in an exotic white turban, embroidered jacket and a mammoth diamond on her hand that glittered distractingly, was Burton’s wife, Elizabeth Taylor. She was not invisible. (The jacket had an ostrich-feather trim!)

Richard was fine in the role, but Elizabeth’s presence in the theater threw everything off-kilter. This was the story of their entire marriage! I had just begun my syndicated column in the New York Daily News and I knew there was trouble in Hell. In fact, 24 hours later, they would split again and for good.

So, it was with a fairly fresh perspective I attended the new production of “Equus” at the Broadhurst Theatre, starring Richard Griffiths as Dysart and Daniel Radcliffe as Strang. This time, there were no diamond-encrusted distractions, but a monumentally compelling 2 hour 1/3 of theater, marvelously directed by Thea Sharrock.

Griffiths, Radcliffe, Kate Mulgrew, Carolyn McCormick, T. Ryder Smith, Anna Camp and Sandra Shipley deliver splendid performances. Griffiths is the embodiment of frustration and humanity, a healer whose life is so threadbare he comes to envy the madness, the passion of his young patient. He decries the “cure,” which leaves the children he treats free of torment, but often with nothing for replacement. His final speech, a sad and eloquent acceptance of his duty to soothe, is tear-inducing.

As for Daniel Radcliffe, as the boy who transfers his love for Jesus to a worship of horses — they are gods who will see and judge his sins — I review his performance by saying that he has submerged himself so completely in this role that one searches in vain for any vestige of Harry Potter. He commands the stage, and fully deserved the tumultuous bravos at the curtain call. (The standing ovation for “Equus” was not the now-routine “let’s stretch-our-legs” exercise.)

And let me give a shout out to the remarkable actors who portray the horses, their faces hidden by beautiful and sinister wire masks — Collin Baja, Tyrone A. Jackson, Spencer Liff, Adesola Osakalumi and Marc Spaulding. Thoroughbreds, all!

Associated Press, Michael Kuchwara – Let’s get to the reason you folks bought tickets: Daniel Radcliffe in the nude. And yes, he can act on stage — quite well, it turns out.

The screen star of all those “Harry Potter” movies brings a disarming vulnerability and touching desperation to the role of Alan Strang, the tormented stable boy who blinds horses in “Equus,” Peter Shaffer’s hit of more than three decades ago. It’s now being revived on Broadway after a successful London engagement last year.

The young actor’s voice is strong, and Radcliffe doesn’t shrink from the physicality of the part. That includes doffing all his clothes during the play’s climactic moments. But then, he literally throws himself into the role in a production chock full of startling, imaginative theatrics.

Director Thea Sharrock, taking a cue from the original staging, has given the play a compelling, arenalike flavor. Some audience members sit in two tiers above the stage and look down on the action. The story is played out on a physically spare set (designed by John Napier) containing a collection of moveable black cubes that serve as furniture. The exquisite lighting, much of it ominous shadows, is by David Hersey.

“Equus” — the Latin word for horse — is as much a mystery as it is a melodrama rife with pyschosexual and religious overtones. Why did the disturbed youth blind those magnificent creatures? It’s a question asked by a psychiatrist (played by Richard Griffiths), a man amazed by the boy’s fierce volatility. The doctor begins to debate his own arid existence — his “professional menopause” matched by an equally unsatisfying marriage.

When “Equus” opened on Broadway in 1974, it starred Anthony Hopkins as psychiatrist Martin Dysart. He was followed by other starry performers such as Richard Burton and Anthony Perkins. Griffiths, a Tony winner for “The History Boys,” doesn’t exude that star wattage, but in his own way, his take on the role works. The actor is deceptively low key, giving an avuncular, conversational performance. It’s best moments occur quietly as he slowly earns the young man’s confidence in an effort to learn why the lad committed such a heinous act.

The play strains in presenting Alan’s turbulent home life, a strict overbearing father (T. Ryder Smith) and quivery, religious mother (Carolyn McCormick). It also falters during the wordy conversations between Dysart and a local magistrate (the overwrought Kate Mulgrew), the woman who sets the story in motion.

Far better are the brief scenes between Alan and the young woman who works at the stable. She’s portrayed by the appealing Anna Camp, whose unaffected naturalness is a welcome anecdote to some of the play’s more emotionally florid family confrontations.

Visually, there are some stunning effects. “Equus” celebrates ritual, particularly in its portrayal of the horses. These splendid steeds are mimed by a half-dozen actors wearing horse masks of caged steel and high steel hoofs. They stalk the stage at various points during the action. Their movements, created by Fin Walker, are sinuous, almost erotic in nature.

That eroticism is a big part of Shaffer’s story: Alan’s attraction to Nugget, the lead horse, portrayed by the commanding Lorenzo Pisoni. The horse’s spirited freedom excites the young man, particularly when compared to the boy’s emotionally claustrophobic family.

The animal unlocks a kind of untamed passion in the youth, a desire that the psychiatrist wants to control or at least understand. But that control comes at a price, a price the playwright seems to suggest at the end of the evening that may be too high.

Chicago Tribune, Chris Jones – Daniel Radcliffe’s fresh and moving Broadway debut in Peter Shaffer’s “Equus” reveals at least two things about the handsome teenage movie star known throughout the world as Harry Potter.

He has some promising stage-acting chops.

And he’s a brave young man.

The most obvious evidence of that bravery is the nudity required by Shaffer’s 1973 drama, a formalist, ritualistic play that traces a child psychologist’s breakthrough with a violent young patient who was remanded by the English court after blinding several horses.

Since an ill-fated sexual encounter with a girl named Jill (the chirpy Anna Camp) is at the heart of young Alan Strang’s problems, the nakedness required from Radcliffe is prolonged. And in an age when almost every item in an audience’s pocket can take a picture, it surely required an admirable comfort level with both brand subversion and personal revelation.

But then, personal revelation is what “Equus” is all about.

Its central conceit is that Dysart, the psychologist who treats Strang, comes to envy the intensity of the young man’s passions and to contrast them with the quotidian agonies of a prosaic, middle-age existence. The device of the shrink being in bigger trouble than the patient seems familiar, even hackneyed today, but Shaffer’s much-copied drama was revelatory in its day. Here was a play that popularized some of the ideas that came out of those 1960s fringe-theater writhings in London and New York and added a literary bent to boot.

Thea Sharrock’s production from London is a simple but nonetheless distinctive staging. It moves rapidly, balancing the sometimes-indulgent verbosity of the script. It is shrewdly lit by David Hersey—at one point, Alan’s cold father ( T. Ryder Smith) looks like a hollow-eyed corpse. But only for an instant. The show is faithful to Shaffer’s dramaturgical schemata—handsome, masked men play the equine characters and John Napier’s stage design recalls a classical arena. Or maybe an operating theater.

Some audience members watch the action from an on-stage balcony, as if Sharrock was playing with the celebrity of her star, who literally gets peered at from all sides.

This is not some dazzling reinvention of the play—and the climax of the show doesn’t pack the oomph it might. But many nuggets lie under its surface.

Including the casting of Richard Griffiths. Thanks to the movie, most people associate Dysart with Richard Burton—a handsome man whose fall toward desperation felt like a celebrity going on a bender.

Griffiths is a movie star himself. But he’s a very different physical type. He moves awkwardly—and he backs away from the script’s opportunities for verbal flourish, leaning into his lines reluctantly. Some of them almost get lost in his cigarette smoke.

Perhaps Griffiths goes too far in that direction. But the effect of this very fine performer’s work is to show us a Dysart with a great deal at stake. You believe he’s on the edge. You believe the story of two naked teenagers would fill him with excitement and existential terror. And thus, as Shaffer surely intended, you start to realize you scratch only the surface of the limited passions of your own life.

Washington Post, Peter Marks – He’s such a forthright, stouthearted lad, our Daniel Radcliffe. These attributes always serve him well, whether he’s being subjected to late-night TV ribbing by Conan O’Brien or playing that magical movie character — you know, whatshisname, the one with the round specs and the scar on his forehead? (Wait: It’ll come to me.)

So now he has gone and repurposed all that pluck for a role on Broadway that has him engaged in dark art rather than the dark arts: that of Alan Strang, the wildly disturbed teenager who blinds six horses in Peter Shaffer’s ’70s psychiatric drama, “Equus.”

This is Radcliffe’s first serious stage portrayal, and though his contribution won’t blow you away, it does get a basic job done. Small-framed and fit-looking, with a rivulet of scruffy beard fringing his jawline, the 19-year-old Radcliffe portrays Alan as a lost man-child drifting needily into the orbit of a shrink, who recognizes in his new patient the rapture missing from his own sterile existence.

The doctor is played, fortunately, by the gifted Richard Griffiths, who it just so happens is a nasty Muggle in all those, uh, Barry Trotter movies. (He also won a Tony as the unorthodox teacher in Alan Bennett’s “The History Boys.”) Thus in this erratic revival of “Equus,” which opened Thursday night at the Broadhurst Theatre, there is a core of leading-player technical proficiency. Even though the play itself comes across now as a solemn, stately affair, involving a therapeutic “mystery” so stuffed with transparent clues that a freshman psychology major could crack it.

“Equus” was a major force the first time it was on Broadway, where it ran for more than 1,200 performances and attracted a succession of magnetic actors (Anthony Hopkins, Richard Burton and Anthony Perkins, among them) to the role of Martin Dysart, the passion-starved child psychiatrist. With the casting of Radcliffe — whose bare torso is, with reason, the production’s poster art — the show’s balance of star power shifts to the younger character. It’s not at all clear that this is good for the story, for “Equus” is perhaps more about an older man’s yearning for some kind of spiritual renewal than it is about the roots of a boy’s pathological behavior.

Director Thea Sharrock, who first staged this production with Radcliffe and Griffiths in London, goes in mostly for a nostalgic embrace of the original’s highly theatrical staging, though she seems to crank up the fog and smoke. As when it made its debut here in 1974, “Equus” is presented as if it were a riff on classical drama. The set — John Napier returns as designer of costumes and scenery — is a minimally adorned arena, ringed with the stalls of the ill-fated horses, played by six lean, well-muscled actors.

The horse’s heads, as of yore, are sculptural and mounted on the actors’ shoulders. As with the original, too, some spectators are seated on or, in this case, above the stage. Just asking: If one were concerned about a dated dimension to the piece — which the playwright himself makes mention of in his program notes — why wouldn’t there have been more of an effort to give this new incarnation an original look?

Some of the acting is impressive, particularly by Anna Camp as a vibrant young woman whose courting of Alan sets in motion his psychosexual crime. A few other performances are seriously misdirected, such as that of Kate Mulgrew, who plays the secondary role of a local magistrate so operatically that she threatens to transform the evening into “Aida.” As Alan’s parents, Carolyn McCormick and T. Ryder Smith turn in rather gray portrayals.

Radcliffe fares best when conveying Alan’s boyish confusion. He isn’t an especially menacing presence, so there is not much sense of Alan’s explosive side, of the damaged, untamed nature that psychiatry must “cure.” (One of the play’s more antique notions is how it romanticizes Alan’s violent streak, as if there were something beautiful and artistic about his illness.)

As a result, the scenes between Alan and the doctor, while intelligently acted — Griffiths gets right the tuning-in skills of a professional listener — don’t ever become galvanizing tests of will; for a play seeking to tell us something about passion, the proceedings remain remarkably unimpassioned.