Excerpts from the reviews:

“Merely hearing the play aloud at Barter reminds one that deft playwrighting still must be measured against Shakespeare’s work, despite ‘Hamlet’s impossible elements. Who else could – or has – blended elements of the supernatural, gentle comedy and horrific tragedy?. . . Director Stutts has delivered a ‘Hamlet’ that is clear in the telling and feels cohesive – except that it lacks the glow of tragedy. That there are problems opens up the entire realm of theatrical debate, firstly because ‘Hamlet’ is not something you get, ‘Hamlet’ is something you aspire to. . . . The role can be played a thousand ways; choose your major stroke . . . John Hardy isn’t bad – he just seems [directorially] neglected. . . . Tragic glow and a range of other moods are skillfully personified by T. Ryder Smith as Laertes, who brings a Keith Richards raffishness to his character’s lighter moments early on, the builds steadily into something deft, haunting and authentic. Good show. . . It felt a privilege to view something immortal and extremely difficult . . . the static of opinion or connoisseurship didn’t block me from reveling anew in ‘Hamlet’s contrariness and brilliance . . .“ – Robert Weisfeld, The Abingdon-Virginian

Full reviews

The Abindgdon Virginian, Robert Weisfeld – Crossing the Bard: Thank God, Barter’s production of Hamlet, Shakespeare’s timeless revenge tragedy (why do critics nowadays steer so clear of this word?), isn’t Spamlet. It’s a timely and – to me – welcome Barter Theatre revival which hasn’t been mounted in half a century of the theatre’s illustrious history. The Bard himself surfaced several days ago in the news, as Southeby’s in London announced the Dec 11th sale of a 1602 land deed for Shakespeare’s acquiring of 107 Stratford-upon-Avon suburban acreage. The playwright, then 38, plunked down 320 pounds, a lot of money in the 17th century. So will the document’s eventual owner, who will have to shell out at least $400,000 for the acquisition of the deed – written, according to scholars, the year of or the year before the playwright’s publication of Hamlet.

A regional theatre critic was seen in print to recall a university prof. who pointed out that Hamlet is bad literature but terrific theatre, or some such misguided blather. Wrong again: Hamlet looks just perfect on paper. But elements in the writing of its title character make it an impossible role, riddled with fascinating contradictions, psychological morass, teasing sexual perambulations, vanity and snobbery, moral dilemma, depressive dark genius and at the risk of making it sound superficial, great masculine beauty – made more fascinating because it is doomed. All any actor, director and cast can do with Hamlet is take a brave leap into something so rich it is probably impossible to touch all the touchstones.

Merely hearing the play aloud at Barter reminds one that deft playwriting still must be measured against Shakespeare’s work despite Hamlet’s impossible elements. Who else could – or has – blended elements of the supernatural, gentle comedy and horrific tragedy in a way that prefigures Freud and Ibsen, who must have dug diving into Hamlet. Hamlet may be the penultimate best.

On a personal note, the brooding prince of Denmark is especially welcome, since the last Barter production your sometimes grudging critic saw was a crowd-pleasing piece of utter tripe nicknamed by me WMKS: Where Music Kills Drama. It hurts me to see Barter misused for these trifling coal-saga salutes – but who’s to be blamed if audiences devour it?

Watching Shakespeare is a discipline; and far too many of you have been victimized by Bill in an earlier era of acting when playing Shakespeare was all about the voice. Today, it’s pretty much agreed-upon that if the acting of Shakespeare isn’t self-explanatory, it’s not being done correctly. Shakespeare was a playwright who aimed his work for popular culture, and I can remember when Bob Porterfield always operated his seasons with same. The results were, naturally, variable. But audiences in southwest Virginia felt a great pride about dressing up and seeing Shakespeare; and were guaranteed productions of great visual beauty, even if period theatre wasn’t their thing. Students at the time were all bused in to partake of the Bard – and I think it was good for us. For the most disinterested, it was at least about learning to be quiet and sit down – like going to church and school. All these things are, you know, gone for now, and I don’t see that their absence is an advantage of any sort. Anyway, I believe that if you are interested in theatre at all, it’s pretty inexcusable not to take in Hamlet. Now really.

Barter’s production, playing through November 23rd, clocks in at 2 hours and 45 minutes, counting intermission and I am here to tell you Saturday evening did not drag. Director Will Stutts has delivered a Hamlet that is clear in its telling and feels cohesive – except that it lacks the glow of tragedy. That there are problems open up the entire realm of theatrical debate, firstly because Hamlet is not something you get. Hamlet is something you aspire to.

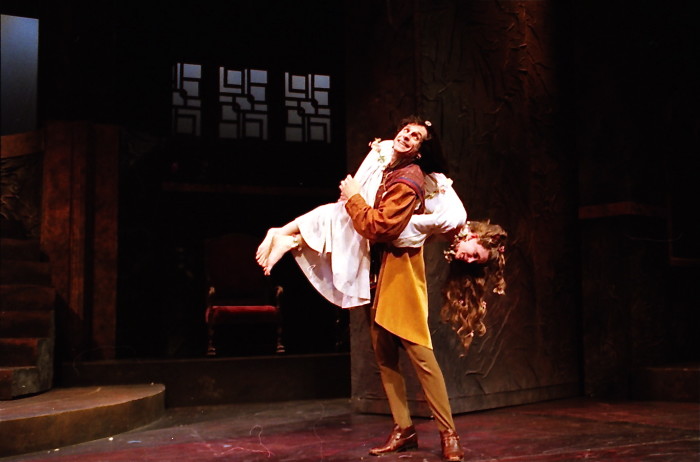

Stutts has been acclaimed for his Barter acting performances. Regretfully, I missed his Atticus Finch; thereafter didn’t care for his cousin Tallulah: but thought his Salieri in Amadeus quite fine indeed. An acting model of technical, cool expertise, Stutts luckily has something else – star presence – but I suspect he may be too detached a director to impart the secret of this to an actor who sorely needs it. Hamlet, after all, even if it is rendered sensibly, is still a role that calls for preening touches of peacock and sweet depressiveness, delirium and danger. I believe I have observed enough of John Hardy’s work to know the right directorial tender loving care could help him make an emotional breakthrough as an artist, and render Hamlet as well. The role can be played a thousand ways; choose your major stroke. Amorous, intellectual, fierce, rebellious, irresolute, elegant, furious, swashbuckling, guilt-ridden, etc. hardy isn’t bad – he just seems neglected.

And looks it. Not that the attractive actor looks badly – but no one seems to have lavished the care deserving of the title role upon him. Costumed to a disadvantage, is physical calling card for playing classical roles – strong runner’s legs – aren’t shown to advantage. Given his natural bent for playing characters wound tightly, this could have been a small, powerful, manic Hamlet – something tailored to Hardy’s interpretation of the title role. All great roles must be filtered through the natural personality of the actor, you see. Never should anyone underestimate the importance of physical appeal in star parts. For that reason, Hardy probably should have been blonded (a great many prominent Hamlets were – including Olivier) revealing a different Hardy even to himself, and adding a touch of star dazzle. Hardy’s forte at Barter has been playing proles – but here he needs to conjure up a period Danish prince – a leap of self-faith for any actor.

Nor did this viewer feel Hardy had been given enough assistance in registering his character’s anguish, brutality, sensuality, obsessiveness and depressive nature. What remained was a respectable performance that didn’t do justice most of all to the actor himself.

Similarly, Suzanne Boulee didn’t find herself in Ophelia. Although physically delicate, Boulee hasn’t the pre-Raphaelite visage or personality to join the school of wisteria-trailing Ophelias – fine only if one is Lillian Gish. That her character’d descent into madness wasn’t directed as something stark, grisly, unkempt and terrifying robbed Boulee of an interesting opportunity. This actress is an unorthodox leading lady – like a Jennifer Jason Leigh – but here someone has gotten her to chirp to suggest youth. It doesn’t help that Ophelia’s drowned body is dry asa bone – along with every eye in the house.

This critic is a fan of much of work of T. Cat Ford – to the point of playing T. Cat Ford casting games. Ford’s Queen Gertrude (one of Shakespeare’s most underrated roles) does have the glow of tragedy. But her big scene gets staged on a teeny bench instead of a bed and the assignment gets carried out by Ford and Hardy minus any of the fascinating, shifting, and sometimes incestuous dynamic Shakespeare wrote that has kept Shakespearean scholars riveted for centuries. Neither does Ford seem to have been drawn into her character’s passive-aggressive, sexy, conceited, shallow, moving little psychological world. Perplexing.

Tragic glow and a range of other moods are skillfully personified by T. Ryder Smith as Laertes, who brings a Keith Richards raffishness to his character’s lighter moments early on, then builds steadily into something deft, haunting and authentic. Good show.

Likewise Frank Lowe’s very gentle comic touch as Polonius. But this critic contends that an approach to this role not wholly innocent makes for a more satisfying theatrical experience for both actor and audience – and believes Lowe is up to the task. Nor has anyone seen fit to urge Nicholas Piper to take his devoted friend role, Horatio, beyond skillful handling of the text. As comrades go – or expire – Hardy and Piper fail to click.

Gannon McHale’s first act performance seemed phoned in on Saturday night, suggesting nothing of a man who has already committed murder and may commit more. Still McHale rose to the second act fore and made his character’s conscience-wrestling a thing of expertise. And yet . . . If only Stutts had McHale’s rages to rumble up from the gut, instead of lying caught in his throat.

Eugene Woolf gets robbed as the celebrated ghost of Hamlet’s father. Reduced to mouthing along with a simultaneous voiceover, Woolf is even cheated of the actor’s opportunity for in-the-moment interpretation – one of the reason’s actors must act. His American Gothic face – perfect for a mournful king – remains concealed instead of horrifically altered by death and visible; nor has he been instructed to do what vengeful ghosts do – howl, rage cut loose and raise the dead. Why one of his entrances did not come from the production’s stage right grave is mystifying, why he was several other ineffective places, excluding stage right’s turret, equally so. But Woolf, a shy, deep actor gives Hamlet’s humble gravedigger a gentle, understated charm – a clue to his potential as a unique character persona.

Mark Filiaci and Todd Scofield bring charm and that elusive click to their roles of compatriots Guildenstern and Rosencrantz – small plums, gently (and funnily) rendered by young actors with personality and the slightly stage-shy hesitance of youth.

The traveling band of actors hamlet calls for have been reduced to two: bring on First Light, citizens for walk-ons, anyone!

The production’s tech elements are as worthy of discourse and dissent as the actors. Frank Ludwig’s set uses the space effectively, but has elements that puzzle: Metallic, almost deco copper trim, peculiar insets downstage that resemble, again, deco water fountains in old movie palaces; and what looks like modern sliding glass doors at the top of the set’s stairway revealing sunny skies in old, dark Denmark – bury my Hamlet at Forest Lawn.

A. C. Hickcox’ lighting seemed too warm, too amber, in Act One; nor was dank Denmark rendered by the sound of Stormy stark – storms did not rage, winds did not howl – but curious, uneven music, once mistaking moog for mood begged to be overlooked.

The costumes, an illusion-shattering grab-bag of everything under the sun from Elizabethan to Andrew Jackson, from Old Dixie to the Mambo Kings, are better left unregarded. But I must say that not costuming the ensemble in a uniform period manner divested this hamlet of its economic class differences – a mistake as it turns out.

Goodness, all this quibbling lends readers the impression this critic didn’t highly regard being at his post on Saturday Night. Nothing could be further from the truth – I enjoyed every moment, even wrong ones, of the whole Dane thing; indeed, to a great extent re-identified with the Danish prince’s restless, stormy moodiness, as attentive viewers are wont to do. It felt a privilege to view something immortal and extremely difficult mounted here, locally. The static of opinion or connoisseurship didn’t block me from reveling anew in Hamlet’s contrariness and brilliance; and perhaps that means it is anything but unplayable.

Yet I cannot help but recall something I heard famed internal drama teacher Stella Adler say in a seminar, when a young actress was wrestling to find the majesty of Elizabeth 1: “Remember, darling, Elizabeth was a very big star in her day.” 11.12.1997

[previous] [next]