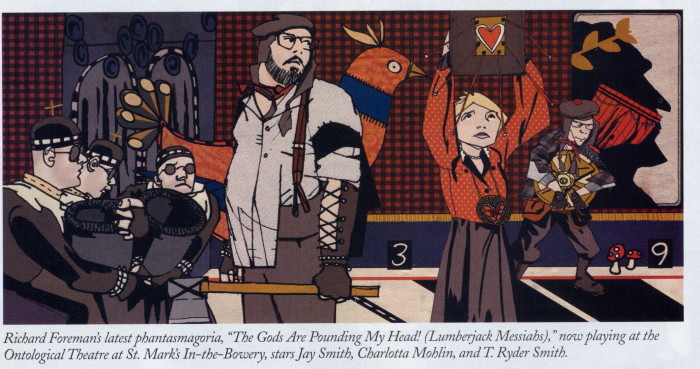

Photos by Paula Court and Tom Brazil

Above: Charlotta Mohlin, Jay Smith, T. Ryder Smith, ensemble

Above: photo by Tina Barney, from her book ‘Players’.

tina barney website here

Excerpts from the reviews

Full reviews below

“An extravaganza of tightly orchestrated hallucinogenic visual effects, bruising slapstick, and intense, cryptic lines that suggest a philosophy student after too many sleepless nights of books and Benzadrine . . . As majestically mad and funny as any Foreman spectacle, it also leaves you feeling more than a little sad . . . A splintered portrait of Dutch and Frenchie, two ineffectual lumberjacks who are ready to hang up the wood-clearing tools of their trade . . . While the subject of ‘Gods’ may be philosophical fatigue, the show is hardly lacking in . . . electrical theatrical energy . . . Foreman crams onto his stage more carefully choreographed frenzy and eye-popping bedazzlement than are found in most Broadway musicals . . . The character of Maude is embodied most beguilingly by Charlotta Mohlin . . . The Messers. Smith are terrific in summoning the exasperated, futility-stricken Foreman prototype in different, exceedingly stylized ways . . . “ Ben Brantley, The New York Times

“In Foreman’s dramatic landscape, you never know quite where you are, and the figures in this late picture from his atelier have a soft, waxy helplessness that makes them both less individual and infinitely sadder and more moving. They seem so indecisive and in such pain about what to do next that the Ontological air feels thick for once with compassion rather than the buzz of conflicting alpha waves. . . . Where the world of his previous pieces has seemed to be a self-contained madcap land of delights, this newly postulated planet feels both emptier and more chillingly like our own. . . . Amazingly, the overriding wistfulness doesn’t prevent both Smiths from giving rich, incisive performances, while Mohlin, though granted few lines, amply makes up for the lack with her expressive eyes and vivacious body English. After decades of extravagant, rackety fun, this piece shows Foreman being pensive, somber, and very nearly tragic.” Michael Feingold, The Village Voice

“Dutch takes and retakes his breath, peering high before speaking – then hits the floorboards like a felled sequoia . . . Boon companion Fenchie’s gaze simmers with defiant melancholy, and, when Maude appears, all tensile glances that steel when she’s not cutting them adrift . . . This expertly played caroming bout of mismatched, sidelong glimpses becomes the galvanizing ‘dance’ on Foreman’s gushing and emptying stage . . . As heartening as it is based on a hopeless quaff, and as visually sumptuous as they come, while going dark, dark, dark . . . ” Alan Lockwood, The New York Press

“It’s probably no longer accurate to call Foreman’s work experimental. For more than 30 years now, his excursions into the cluttered attic of his own mind have developed recognizable conventions: a jumbled collage of a stage; strings painted to look like dotted lines that create divisions of space; allusive, repetitive dialogue; sudden crashes of dense sound, and Foreman himself overseeing performances from the center of the audience . . . The production also mourns a lost time when people were full and complicated beings. Now, as a deep voice intones over loudspeakers, we’re pancake people, wan and flat. Our two lumberjacks, having outlived their “time in the sun,” don’t know what to do with themselves. Sensitive, soft- spoken Dutch (Jay Smith, the one in pearls) questions the state of his world with wide-eyed wariness, while the more jaded Frenchie (T. Ryder Smith, with an Irish accent) accepts his lot with a cocky swagger. Between them ricochets Maude (the mercurial Charlotta Mohlin), a mysterious woman drawn from a Tennyson poem . . . Even if Foreman’s work isn’t your thing, his shows can produce a weird, mesmeric pull. Sudden moments of recognition – of the lumberjacks’ longing, for instance, or of their claustrophobic fear of the end – can take you by surprise. Although the show may be an ending for Foreman as well, a stubborn hope remains. The lumberjacks speak of absent gods, but they point bravely ahead, and occasionally break into lovely choral harmony. In spite of the dying world around them, they still have a song in their souls.“ Gordon Cox, New York Newsday

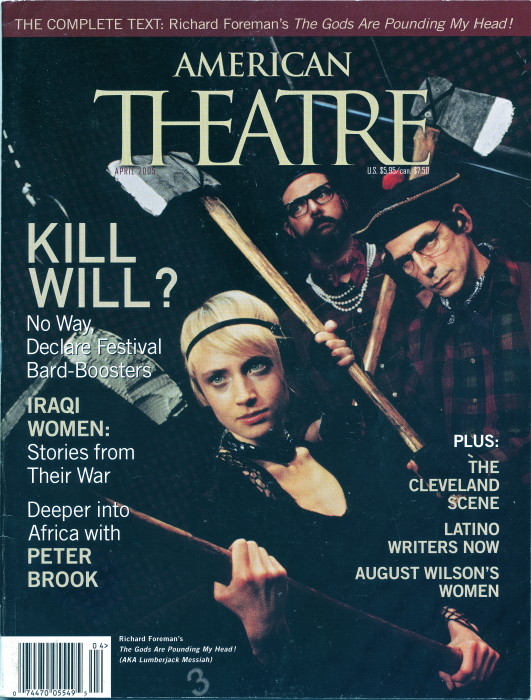

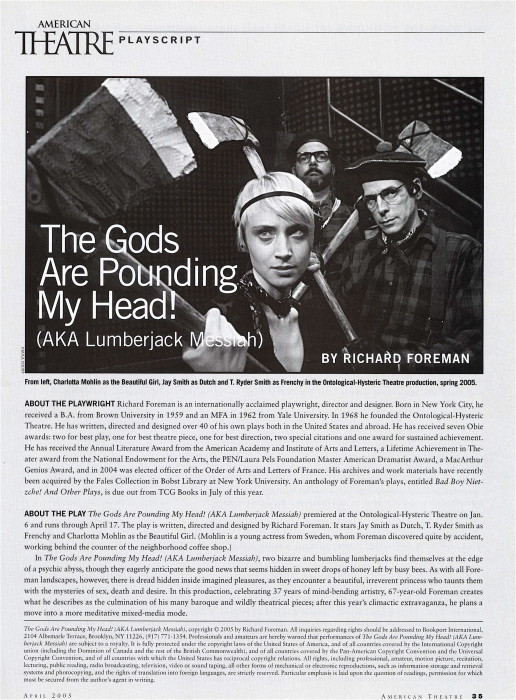

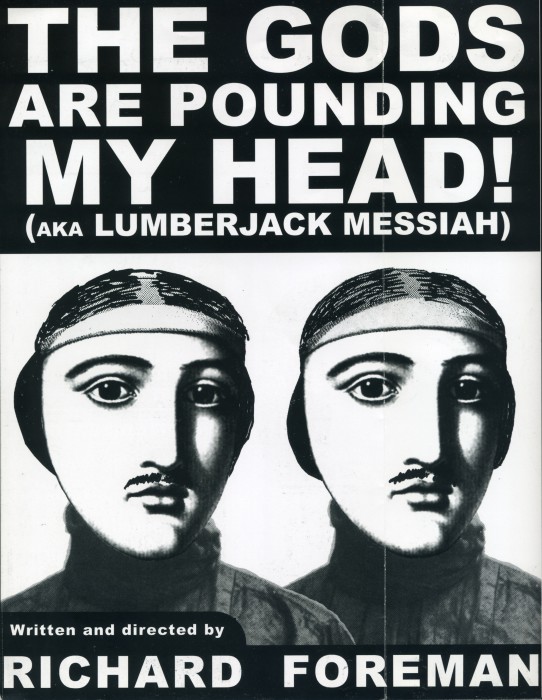

Publicity

Above: New Yorker magazine cartoon

Offstage

Above: Closing night; cast and crew, and some colleagues from The Wooster Group who stopped by from down the street after their own show.

Back: Chris Mirto, Calvin J. Alden, Richard Foreman, Matthew Hunter Griffin, Daniel Allen Nelson, Brendan Regimbal, Jay Smith, Shannon Sindelar, Paul Di Pietro, Kate Valk, Jim Fletcher, Scott Shepherd. Front: T. Ryder Smith, Stephanie Silver, Charlotta Mohlin, Morgan von Prelle Pecelli, Theresa Bucheister

Above: same as above, with Anthony Cerrato at right.

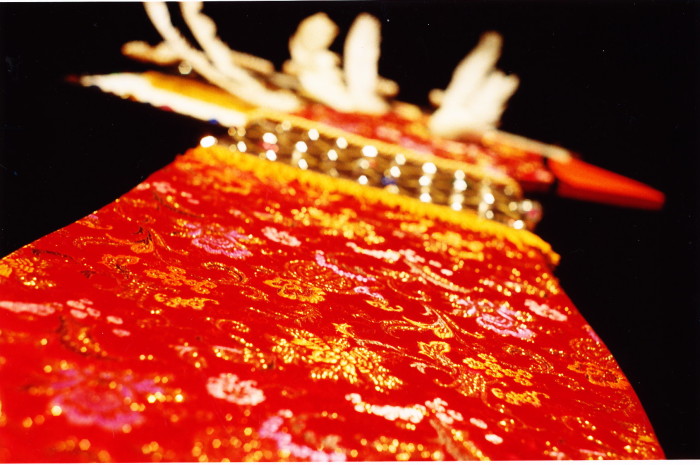

Below: details of the set.

Update 2015

l to r: Jan Leslie Harding, Richard Foreman, T. Ryder Smith

at McNally Jackson books, NYC, following a talk Richard gave about his book “Manifestos and Essays”

Photo by Yvonne Brooks

Full reviews

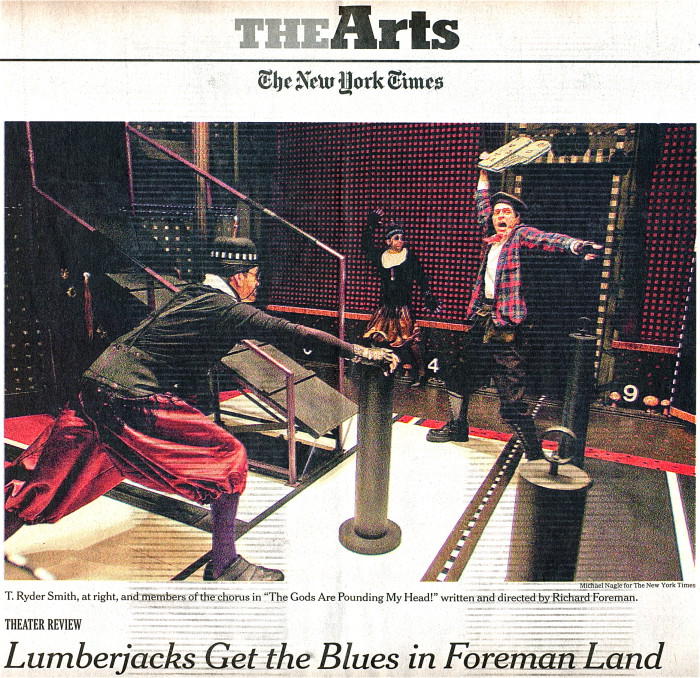

New York Times, Ben Brantley – Lumberjacks Get the Blues in Foreman Land. Behold the mighty lumberjack, standing tall in his garb of disheveled black tie and pearls. Watch as he raises high his ax, poised to strike a felling blow. See the ax slip from his hands, tumbling to the ground with a quiet thud, as the woodsman just stands there, empty-handed and empty-eyed. Come to think of it, he has been looking awfully tired and shaky, like someone who would rather be under the covers than in the forest. Besides, he keeps hearing these eerie and discouraging voices in his head.

Even lumberjacks get the cosmic blues in the world of Richard Foreman, the mind-roiling warlock of avant-garde drama, whose latest – and possibly final – play opened last night at his longtime artistic residence, the Ontological Theater at St. Mark’s Church in the East Village, where it is scheduled to run through April 17. The title this time is “The Gods Are Pounding My Head! (a k a Lumberjack Messiah),” a classic name from a writer whose other works include “My Head Was a Sledgehammer” and “Panic! (How to Be Happy).”

In other ways, too, “The Gods Are Pounding My Head!” is entirely typical of Mr. Foreman, the ultimate theater auteur. This show is the customary extravaganza of tightly orchestrated hallucinogenic visual effects, bruising slapstick and intense, cryptic lines that suggest a philosophy student after too many sleepless nights of books and Benzedrine.

But there is something subliminally different about this production. An elegiac note extends from the funereal black that dominates the crazy-quilt set to the look of depletion in the faces of the central characters. “Gods” is as majestically mad and funny as any Foreman spectacle, but it also leaves you feeling more than a little sad.

This is not inappropriate for what appears to be a farewell note of sorts. Mr. Foreman has said he is giving up the kinds of plays he has been creating since 1968, as the Florenz Ziegfeld of downtown theater, to focus on film.

And so, for this valedictory production – written, directed and designed, as always, by Mr. Foreman – he has created a splintered portrait of Dutch (Jay Smith) and Frenchie (T. Ryder Smith), two ineffectual lumberjacks who are ready to hang up the woods-clearing tools of their trade. Anyway, like all of the bewildered big-picture seekers in Foreman Land, they have never been very good at seeing the trees for the forest.

But while the subject of “Gods” may be philosophical fatigue, the show is hardly lacking in the electric theatrical energy expected of Mr. Foreman. As is his wont, he crams onto his pocket-size stage more carefully choregraphed frenzy and eye-popping bedazzlement than are found in most Broadway musicals. His sinister funhouse set is even more replete than usual with oversize toys, from a locomotive (on a very short track) to a sliding board.

The regulation enigmatic, wild-eyed beauty (named Maude, to evoke the girl in the Tennyson poem, and embodied most beguilingly by Charlotta Mohlin) is again on hand to bedevil the boys and to share their fears and frustrations. The signature Foreman chorus of gnomelike, identically clad creatures run on and off the stage, looking like crosses between bellboys and harem girls, while serving up props like giant black Fabergé-style eggs and effigies of crowned heads without bodies.

The Messrs. Smith are terrific in summoning the exasperated, futility-stricken Foreman prototype in different, exceedingly stylized ways. Dutch is a big lug with a wilting voice; Frenchie is a lean, stone-faced fellow with a deadpan Scottish drawl. Along with Maude, who laments the absence of real men, they ride the train (and simulate copulation with it), become stuck on the sliding board and stagger beneath the weight of giant military medals. Like all Foreman characters, they also hurl themselves against the walls and fall down a lot.

The elliptical, disjointed text – spoken live by the performers and in godlike recorded voice-overs by Mr. Foreman – mixes nursery rhymes, Victorian poetry and assorted philosophical postulations that are offered with tentative hope and immediately evaporate. A sense of disgust with a society without substance informs much of what is said. The disembodied voice speaks of how people of “depth and intricacy” have been replaced by others who are “just surface only” in a “brand-new, paper-thin world.”

Throughout his long and influential career, Mr. Foreman has compellingly used purely theatrical surfaces, from variations on commedia dell’arte characters to papier-mâché props, to uncover seething depths. In his hands, a silly-looking, homemade playhouse has been turned repeatedly into a limitless cosmic playground made for exploration and getting lost.

It is hard to imagine the same sensibility working quite as well in film, which is necessarily a more literal-minded medium. In the meantime, theatergoers used to getting high on Mr. Foreman’s annual productions are likely to feel withdrawal pangs for years to come. 1-19-05

Time Out NY, David Cote – Ontological-Hysteric Theatre founder Richard Foreman has declared that The Gods Are Pounding My Head! (aka Lumberjack Messiah) will be his last chamber play. While the avant-garde legend plans to create stage works that incorporate video and live actors, he’ll no longer write, design and direct the densely layered sensory attacks that have become a perennial attraction upstairs at St. Mark’s Church. How to honor Foreman’s 37 years of experimentation that have inspired so many younger directors and enriched the American theatrical vocabulary?

Well, not by embalming him in encomiums and salaams; he’s not dead, just finished with one phase of his career. And Gods, despite its persistent tone of nostalgia, regret and fear for the future, is not a whimper. Frankly, every Foreman production (at least the ones I’ve seen since 1992) contains equal parts bang and whimper. In this one, the ax-wielding woodsmen Dutch (Jay Smith) and Frenchie (T. Ryder Smith) alternately train their blades on Foreman’s typical fun-house set and lapse into plaintive postulates about “the heart of the world.” Hope is offered by the pixie Maude (Mohlin), who seems to represent both sentimental innocence and the decadent youth with no sense of history or culture. All the disorienting auteur’s trademarks are here—visual and verbal non sequiturs, disruptive music loops, ominous gnomic voiceovers and harsh lights—but there’s a wistful resignation under it all. Next season, Foreman will not be pounding our heads, an ontological fact sure to make us hysteric.

Village Voice, Michael Feingold – Foreman Has The Chops. A kinder, gentler image theater sings a requiem for the barely surviving heart of the world. In place of the tormented philosophers and poetic seekers who’ve been the central figures of most of Richard Foreman’s pieces, The Gods Are Pounding My Head features innocent, befuddled lumberjacks. If that leaves you feeling intellectually cut down, you’re not alone: Hefting their axes, at various points in the roughly 75-minute work, Frenchie (T. Ryder Smith) and Dutch (Jay Smith) hew away at empty spaces or at objects on the set, while loudspeakers fill the air with amplified chops. At one point they even lift their axes, menacingly, at the heart of the planet itself, an object resembling a supersized basketball with aortic valves, rolled onstage to the accompaniment of ominous organ music. The action doesn’t take place on our planet, of course. Or does it? “Suppose I were to postulate that this is [happening] on a planet that moves around the sun,” Dutch asks us. “How would you people deal with that?” Any green planet, after all, might boast lumberjacks. And Foreman periodically fills the sky of his stage, especially at the piece’s heartbreaking end, with identical little green spheres, suggesting antique clocks or Montgolfier balloons, each encircled with a gilded equator of Roman numerals. Is Time running out for us? “Sometimes it works,” says Frenchie hopefully, downing cup after cup of an erratic “magic potion” for which he’s already said it’s too late, while a taped choir softly chants, “Requiem aeternam.” “Sometimes it works.” Slow fade.

Though more earnestly simple than previous Foreman heroes, Frenchie and Dutch are recognizably similar to their predecessors in Foreman’s parade of buddy-antagonist duos. It’s naturally Frenchie, the more astute and worldly wise of the two, who seems to keep clattering down the playground slide stage left. Just as naturally, it’s the soft-spoken, vulnerable Dutch who’s more bedazzled by Maude (Charlotta Mohlin), this play’s edition of the eternal Foreman ingenue-muse-temptress from whom all blessings and torments seem to flow. This time they flow in the form of endless plates, each bearing two fried eggs, sunny-side up. (Foreman’s fascination with the erotic imaging potential of food is unceasing.)

It’s been the continuing paradox of Foreman’s work that his characters have a slippery bas-relief quality, alternately sinking back into being mere fragments of the author’s vision and stepping forward to act with three-dimensional assertiveness. In Foreman’s dramatic landscape, you never know quite where you are, and the figures in this late picture from his atelier have a soft, waxy helplessness that makes them both less individual and infinitely sadder and more moving. They seem so indecisive and in such pain about what to do next that the Ontological air feels thick for once with compassion rather than the buzz of conflicting alpha waves. It’s probably worth noting that the piece contains a good deal less than usual of the slapstick violence and humiliation Foreman regularly visits on his characters; it feels like a plea for reconciliation and an innocent back-to-basics.

In the end, the sense of bleakness prevails, though not without a strong admixture of Foreman’s sumptuous and playful diversions. Where the world of his previous pieces has seemed to be a self-contained madcap land of delights, this newly postulated planet feels both emptier and more chillingly like our own. (Another repeated line: “The action is elsewhere.”) At moments Foreman appears to be saying goodbye to the Judeo-Christian system that’s shaped our civilization: A cascade of objects from the sky includes a pair of stone tablets, though they don’t appear to contain any commandments. Amazingly, the overriding wistfulness doesn’t prevent both Smiths from giving rich, incisive performances, while Mohlin, though granted few lines, amply makes up for the lack with her expressive eyes and vivacious body English. After decades of extravagant, rackety fun, this piece shows Foreman being pensive, somber, and very nearly tragic. Of all the multitude of 19th- and 20th-century artists on whom his work has drawn over the years, this piece summons up the last person I ever dreamed I’d be comparing him to: Beckett. 1.11.05

Village Voice – University Wits.

The Village Voice proudly launches University Wits, a monthly forum of theater reviews by students from some of the finest graduate theater programs in the commutable areaNYU, Columbia, the CUNY Graduate Center, the Yale School of Drama, and A.R.T.’s Institute for Advanced Theater Training at Harvard University. In an era of the theater review as consumer report, our mission is obvious: To expand the theatrical conversation by providing a venue for the next generation of serious theater critics. This first round focuses on Richard Foreman’s new offering, The Gods are Pounding My Head! (AKA Lumberjack Messiah)ostensibly the avant-garde legend’s final stage offering before embarking on a new multimedia adventure revolving around- gasp! – film.

Richard Foreman’s bittersweet prophecy – Stella Gorlin: An alienated locomotive, mighty symbol of the Industrial Revolution, idles in a grotesque graveyard, lounging on a track that leads nowhere. A discarded playground slide rusts against a red plaid wall. Scattered fragments of Victoriana torment the ghosts loitering in The Gods are Pounding My Head!, a sadistic comic requiem. Richard Foreman has created his own Endgame, an oddly serene, post-apocalyptic wasteland of scrap metal and charred skulls. Dripping with a venom and froth, Foreman’s latest work confirms his mastery of ber Brechtian Verfremdung.

At the heart of Foreman’s carefully choreographed chaos are the wry Frenchie (T. Ryder Smith) and the melancholy Dutch (Jay Smith), a pair of lumberjacks drifting aimlessly through the shadowy junkyard of civilization. Too weary to wield their axes, our anti-heroes, played with stylistic deliberation, voice Foreman’s nausea at the decay of intellectual and artistic complexity. In a breathy monotone, Dutch “postulates” endlessly about the relevance of art for the newest generation of shallow “pancake people,” while Frenchie delivers bons mots in a Scottish drawl and frolics with the alluring Maude (Charlotta Mohlin), who wears her heart on her sleeve, literally. She too is a remnant, a flesh and blood reminder of sexual desire. Maude, deliciously played by Mohlin, embodies “the big heart of the world,” slowly crumbling into dust.

Weaving in and out of the action, the chorus of vaudeville soldiers, clad in metallic pantaloons and Prussian helmets adorned with a cross, is a dystopian manifestation of Foreman’s sinister design. These menacing clowns in John Lennon sunglasses creep onstage, stubble-faced and smiling, with ambiguous intent. We never discover this bizarre ensemble’s purpose, making its presence in Foreman’s tableaux simultaneously frightening and hilarious.

The brilliant scenic environment and soundscape anchor Foreman’s goal of disassociation. His startling theatrical vocabulary introduces a paradoxical world in which pictures replace dialogue and spatial and temporal rules no longer apply. Pasting together shards of opposing styles into a disjointed collage, he weaves a dense tapestry of sound and image, comedy and danger. Eerie dings, romantic melodies, the cock of a gun, and Foreman’s booming, messianic voice erupt ominously from the loudspeakers. Out of the soot of this funhouse cemetery sprout marzipan mushrooms while white doves hover amid bouquets of light bulbs, mangled steel piping, and leering human skulls. Glimmers of life endure even on this blasted heath.

In Foreman’s final gesture, Dutch, Frenchie, and Maude guzzle a mysterious “magic elixir,” served in dark grails by the Cirque du Soleil-like chorus. As the lights fade, we hear only the cacophony of empty cups clattering to the floora hauntingly cryptic ending to a production of marvelous intensity. Has Foreman orchestrated a hallucinogenic suicide note? Does he fear that “a world that seems to have lost the thick and multi-textured density of deeply evolved personality” has no room for his artistic expression? The enthusiastic crowd clamoring for tickets at St. Mark’s Church suggests otherwise. Perhaps, like the triumphant mushrooms, art springs eternal, even in the age of Internet pop-ups.

(Stella Gorlin is an M.F.A. student in Dramaturgy at A.R.T.’s Institute for Advance Theater Training at Harvard University.)

Now this is living – Mark Blankenship: The Gods are Pounding My Head! is my first experience of Richard Foreman’s theater, my only chance to witness a downtown legend’s genius. I wonder if I waited too long. Though Gods’ ideas left me buzzing, their execution suggests Foreman has already said goodbye, dismissing his public as “pancake people.”

Pancake people are what Foreman dubs the inhabitants of The Gods’ world. Specifically, they’re three glassy-eyed lumberjacks whose minds and lives are pressed so thin they can barely function. With monotone speech and rigid limbs, they stumble through a world they’re powerless to change.

And their grotesque world needs changing. While a mechanical voice barks about a dying society, everything floods with savage white light. In pith helmets topped with crosses, a silent ensemble flaunts an oversize set of Ten Commandments tablets and giant medals of honor, mocking their meaning as symbols. This horrible chaos might spur revolt, but the lumberjacks only flail at the set with the wrong side of their axes.

The impotent trioand indeed the entire piecemakes a potent allegory for the decline of thought. “Sometimes,” Foreman writes in the program, “I shrink back in horror at a world that seems to have lost the . . . density of deeply evolved personality.” This density gives way to the drones onstage, and it’s easy to wonder if we’re just like them. Do we lurch around like fools and call it a meaningful life?

Foreman’s set compounds the dread implications. Metal bars and pieces of machines litter a stage that’s a gothic-black bedroom on the left and a garden of fake flowers on the right. A living chamber draped with death, an earth made verdant with plastic: The landscape is poisoned by the same entropy that makes the characters buffoons. This vision suffocates: Mindless doom feels inevitable as the lumberjacks thud against another metal pole.

This is why The Gods’ final moment is such a relief. It’s a simple action the three drink desperately from cups of “magic potion”yet it unifies the lumberjacks in a quest to feel something new. Though there’s no hint they’ll succeed, there is hope in the fact that they’re searching. For a moment, the mechanical voice is silent and actions are invested with purpose.

An audience, however, may be frustrated by purpose’s late arrival. For although The Gods is fascinating to think about, it is arduous to watch. It makes sense for this brain-dead world to have one tempo, one volume, and one small set of repeated gestures, but once the pattern is grasped, there are few surprises to keep the mind from wandering. And because he states his intentions so clearly in the program and in the mechanical voice’s refrain about a “paper-thin world”Foreman leaves little room to interpret his work. As though we won’t understand without bludgeoning, he swings The Gods like a hammer, repeating its message over and over until our heads are pounding too.

(Mark Blankenship is an M.F.A. student in Dramaturgy and Dramatic Criticism at the Yale School of Drama.)

Lumberjack grace – T. Nikki Cesare: Richard Foreman’s work often suggests the operatic, and this is especially so in his latest and purportedly last play, The Gods are Pounding My Head! (AKA Lumberjack Messiah). Two weary, postulating lumberjacks, Dutch and Frenchie, brilliantly portrayed by Jay Smith and T. Ryder Smith, are set against the “inevitable psychic disintegration that anticipates the threatened twilight of the West.” Complicating their pondering is the wistful, not-quite-innocent nymphette Maude. Startling, lyrical, and just manipulative enough, Maude, played by the very promising Charlotta Mohlin, intrudes upon Dutch and Frenchie’s elegiac existence like Modernism displacing Romanticist notions of truth and beauty. There is music throughout this playin the explicit sound-scheme (the Kurosawa-esque percussion in the opening being particularly striking), but more notably, in the relationships between the characters themselves. Maude is the extreme chromaticism that emerges from and ultimately undoes Western harmony.

The set, sparser than previous Ontological Hysteric productions, is lumberjack-goth: red-and-black plaid walls adorned with skulls, indecipherable number configurations, and a flock of fake white doves hanging from the ceilingall bifurcated by Foreman’s familiar string and pulley architectonics. Dutch and Frenchie, wearing variations on the plaid theme, are bedecked in pearls and ruffles; diamond bracelets shine from Maude’s wrists. These adornments lend a sensitivity to the lumberjack’s masculinity, while giving way to the undercurrent of aging virility in the juxtaposition between them and this young and agile lumberjill (all gesture, disarming blue eyes, and a voice like a sound effect in its squeals and squeaking). Maude’s androgynous figure belies a certain Eve-like temptation within this expired Eden.

In addition to the three protagonists are Foreman’s usual “expendables,” the stage crew-henchmen: six tights-wearing figures bedecked in crude crowns that might represent a troupe of Mini-me popes. They scuttle among the props and characters like imperial cockroaches caught in the light: never alone, rarely hesitant, always moving back into the shadows. If one were to seek out meaning in this playa paradoxical if not impossible project in itself one might interpret these henchmen as the sky itself, from which items and symbolism tumble. (The sky has fallen: Foreman is no longer writing plays.) Moving across a stage delimited by a locomotive engine stage right and the ladder and slide of a grownup swing set stage left, the characters negotiate the shifting props and significations so that The Gods becomes the work of art as a mechanical reproduction but one touched with grace rather than industrial depersonalization.

Foreman writes of The Gods, “The lumberjacks suffer, in secret, from a broken heart which may indeed be the heart of the world. But, at the end, hope still springs eternal.” The most profound facet of this quietly stunning play is that it does remain hopeful. The three characters, wearing plumage and drinking a “magic potion” until the lights finally go out, are disheartened, but it is difficult to believe that they are heartbroken. Though if it is Foreman’s last play, it will be a melancholy heartbreak after all.

(T. Nikki Cesare is a Ph.D. candidate in Performance Studies at NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts and Managing Editor of TDR: The Drama Review.)

Richard Foreman buries the hatchet? – Paul Menard: For many of New York’s avant-garde theatre types, it’s the most wonderful time of the year. The time when theatrical halls are decked with kewpie dolls and strings are hung across stages with care. The time hen the cold snows of winter are melted away by the warm rays of spotlights aimed directly into theatergoers’ eyes. The time for New York’s own hipster high holiday.

It’s time to see the new Richard Foreman show. And this may be your last chance.

For over three decades, Richard Foreman auteur director and fixture of the avant-garde has created jarring and oddly transcendent masterpieces with his Ontological-Hysteric Theatre. Perhaps best known for his trademark style of Brechtian audience alienation (unemotional acting, cluttered stages crisscrossed with strings, Plexiglas partitions between the actors and audience), Foreman has announced that he’s finally calling it quits after his current show, The Gods are Pounding My Head! (AKA Lumberjack Messiah). When the lights lower on the show’s final performance on April 17, Foreman claims he will no longer return to the renowned Ontological-Hysteric style of theater he first created in 1968. Instead, he intends to pursue filmmaking with collaborator Sophie Haviland.

Richard Foreman retire? What’s next? Cher putting an end to her farewell tour?

Eschewing the more overtly narrative and political structure of last year’s Ontological-Hysteric offering, King Cowboy Rufus Rules the Universe, The Gods represents a return to pure Forman form. The celebrated Foreman strings are still bisecting the claustrophobic stage according to an unknown spatial geometry. But, with actors literally reaching out over the knee-high Plexiglas partition and the once-familiar kewpie dolls replaced by halos of artificial doves, one wonders if Foreman’s theatrical journey is indeed coming to a close.

The Gods is essentially a metaphysical medieval morality talea character’s journey towards salvationfiltered through Foreman’s postmodernist lens. And, boy, postmodernism can be some messy stuff. Two bespectacled lumberjacks, the vulnerable Dutch (Jay Smith) and his wry friend Frenchie (T. Ryder Smith), encounter the youthful Maude (Charlotta Mohlin), who goads the duo through a series of uncanny episodes as they symbolically struggle under the earthly weight of civilization. All the while, a mute chorus, resembling a scruffy papal biker gang, parades handmade props through a jumbled set that includes a primitive train trapped on a tiny track, a playground slide leading nowhere, a wall of red plaid flannel, and a hint of religiosity.

Sonic non-sequiturs (a Tennyson poem or a snippet of My Darling Clementine) abound throughout. But amid the din of electronic buzzing and church organs, it is Foreman’s own modulated voice that comes through strongest. While loyal audience members sit, confronted with the now familiar images of Foreman’s theater coupled with the news of his alleged retirement, onstage lumberjacks exhaust themselves by futilely hammering axes against a stage bereft of trees. Resonantly, Forman (perhaps exhausted himself) intones, “You’ve already seen this before. Therefore it will break your heart.”

For some fans, it surely will.

(Paul Menard is an M.F.A. student in Dramaturgy and Script Development at Columbia University’s School of the Arts.)

Postulations in plaid – Roxane Heinze: Walking into the Ontological-Hysteric space, I am greeted by the expected and yet still somewhat disconcerting image of Richard Foreman standing on his set, observing the audience, his audience. Making sure everyone has a seat, removing over-large bags from spectators who came foolishly expecting space and (relative) comfort, he plays host and overseer to these, his guests. Foreman’s presence is a common thing; in fact, he is the most necessary and pivotal individual in every one of his pieces, The Gods being no exception. So why am I so struck by him this time around? Call it foreshadowing or hindsight, Foreman’s presence onstage anticipates the wistful lumberjacks to come. But Foreman doesn’t need the plaid shirt or the big shoes because he’s the real thing. He stands in front of the house, his casual, droopy demeanor belying the quick and sad wit ever-present in his sharp eyes. He carefully takes in everyone present and allows them to observe him as well. Here is the lumberjack messiah: the wistful, mournful artist observing the ever-changing, and forever changed, world.

Both Dutch and Frenchie, the two lumberjack companions who seem unable to ply their trade, often echo his simple observation of the audience in this dark and poignant performance. There is a sublime sadness, a proud pain that pervades this, the latest of Foreman’s ruminations on the universe as he knows it. Dutch keeps dropping his axe, his tool of identification, in wistful fits of melancholy. A desperate refrain bemoans the death of the three-dimensional person. The “heart of the world” is in danger of being destroyed. Alfred Lloyd Tennyson’s muse from the poem “Come into the Garden Maude” is given flesh to become the Lumberjacks’ lover-muse, who comes bearing curative love potions. Her bright frailty exposes the elusive, easily damaged and forgotten forms of knowledge that the author and therefore the lumberjacks mourn most. The fear of becoming “pancake people” is prevalent as Dutch and Frenchie are overwhelmed by gigantic medals that obscure their identities and force them to walk like squashed cartoon characters. The surface images are suspect for their preposterous boastfulness and lack of substance. The medals Dutch and Frenchie carry become synonymous with their accomplishments (Dutch sings “I still have my medals”), even as the weight of these accomplishments threatens to crush them, indeed flatten them into the pancake people they fear.

Both Jay Smith (Dutch) and T. Ryder Smith (Frenchie) manage to inhabit this world of tartan melancholy with remarkable grace. Their ruminations and “postulations” construct a genuinely heart-rending mood of loss and memorial. It is clear, both from the production and the program notes, that Foreman feels that his lumberjack days are over; or perhaps more accurately, that there is no longer any room in the world for lumberjacks (a/k/a the avant-garde). The pain is palpable. Mortality is in the air. A world-weariness prevails, notably that of an exhausted, meditative conscience.

But while the death of the avant-garde has been announced, its corpse buried, and its spirit mourned, perhaps there’s still a bit of life in the glorious monster yet. Maybe a small draught of love potion will help?

(Roxanne Heinze is a Ph.D. student in Theater History at the CUNY Graduate Center.)

2.10.2005.

nytheatre.com, Matt Freeman – Richard Foreman’s tenure as East Village mainstay is coming to a close with The Gods Are Pounding My Head! (AKA Lumberjack Messiah). His Ontological Hysteric Theater, at St. Marks Church, has produced 50 of his pieces, a metaphysical, theatrical hodgepodge of symbols, metaphor, and academia. This show, billed as his final one (at least for now), is said to be the culmination of his unique ruminations. The experience of watching The Gods Are Pounding My Head! is one of watching a man wrestle with heady concepts, very much on his own, for an audience of faithful cult-followers. All others need not apply, I fear.

There is a lot that happens in The Gods Are Pounding My Head!, but I’m not sure if they’d qualify as dramatic incidents in any conventional sense. Two lumberjacks named Dutch and Frenchie come across a young blonde nymph named Maude and wander in a dream of technology and biology, or so it seems. The chorus wear black hats with crucifixes on them, bearing everything from black buckets to papier maché heads to large black charts bearing magic square numbers. What is happening? Foreman tells us he’s wrestling with the Western mind, the mind of those who cut down, like lumberjacks, old things to make way for new ones. He fears that this society, as it acquires more and more speed and immediacy, will become more “thin,” that a deeper, more meditative psychology is being supplanted by a wider “super-consciousness” that may or may not be an improvement. To be honest, though, that explanation comes from the program notes. It was not explicitly on the stage.

It’s an argument in modern art: should the art speak for itself without the artist providing his own context (in the form of a statement, for example) or is providing a context part of the art? Why should an artist accept the pre-determined context of what we bring with us when we walk in the door…can’t he put us in another mindset? Or does the theatrical piece that fails to engage without prior explanation lack integrity?

Of course, there’s no solid answer to this question. It’s entirely up to taste, to the audience, and to theoreticians. In Foreman’s defense, he certainly will bring to the surface a person’s inherent prejudices or lack thereof when it comes to art. The casual observer or uninitiated into this sort of active participation, someone who isn’t a big reader of Foucault perhaps, might just find themselves rightly sitting there thinking: “What the heck am I doing here?”

So in reviewing Foreman the question becomes how is this valuable? It is because of the debate it may spark, it isn’t because of the ideas. When the giant paisley bird is rolled onto the stage late in the play, anyone who doesn’t roll their eyes is more than likely so indoctrinated that Foreman would have to literally stand up and say “This random bird means nothing to anyone but me!” And even then, they’d likely applaud him as a genius. But there are charms in the performances, humorous juxtapositions of language and image, that are intentional and very under control. He’s an artist, above all things, being allowed to work purely in his medium, and for that reason alone, he’s an increasingly rare bird.

There were moments of stagecraft here that I was simply floored by, and others that left me utterly cold. Besides a dedicated and specific chorus, there are three actors on the stage to try to decipher: Jay Smith’s odd deadpan as Dutch; T. Ryder Smith’s laconic Frenchie, and Charlotta Mohlin’s pixie Maude. As performers, they are all about as different in style and appearance as possible, absolutely unsettling as a trio. The language of play did more for me than the images, which often seemed to be coming from a Jungian mish-mash, but the mix of the visceral (a giant encased heart) and the technological (an engine that rides back on forth on a track) creates a gut-reaction that rises above simple understanding.

The final result was a resounding shrug of my shoulders, at first. But as I’ve taken time away from the actual performance, I’ve realized that it certainly challenged my sensibilities. And really, when so much of theatre is either preaching to the converted or grappling with such immense questions as “Can I be happy?” or “How do single moms do it?” the questions of modern art, consciousness, and the Western mind are worth at least trying to tap into. And few, I’d say try with as much audacity and bravery as Foreman. 1-11-05

CurtainUp, Jenny Sandman – It’s that time of year again. Richard Foreman’s latest, The Gods Are Pounding My Head! (AKA Lumberjack Messiah) is running at St. Mark’s Church and all’s right in the world. But this one is a little different from his offerings in the past few years. It’s sadder, more elegiac, and it’s sparer, both physically and metaphysically.

The stage is comparatively bare unlike other Foreman shows which are typically filled with detritus. Foreman fans will find that The Gods Are Pounding My Head! has fewer props and much less stage decoration than they have come to expect. Consequently, the space feels less cluttered and so does the script — without a sensory barrage and hardly any overt phallic symbols or sexual innuendoes.

The set is counterbalanced by a locomotive on one side and a large slide on the other, with very little in between. What about the subtitle? The axes the actors carry and the red checked flannel wall covering are the only visual lumberjack references.

There are hints of Greek Orthodox influences in the costumes and props. The minimal lines andr sound cues leaves the audience plenty of space to consider each verbal clue.

This new play does feature the trademark Foreman humor: at one point T. Ryder Smith cries out, “My eyes are burning like two fried eggs on a hot griddle”–and lo and behold, out come two fried eggs on a hot griddle, to his dismay.

As Foreman puts it, the lumberjacks, Dutch and Frenchie–played by Foreman regulars, the above mentioned T. Ryder Smith and Jay Smith– “suffer from a broken heart,”. They are joined by newcomer Charlotta Mohlin, discovered by Foreman in a coffee shop near St. Mark’s Church, as Maude, The lumberjacks rail against the “pancake people,” those modern souls stretched thin by too much information. These people will “break the heart of the world,” as well as the already broken ones of the lumberjacksn.

Smith and Smith are old pros at performing Foreman’s unique characters, but Mohlin seems to have an innate gift for Foreman-speak as well. All three are captivating, the men slightly more so with their verbal acrobatics.

Although last year’s King Cowboy Rufus Rules the Universe! was widely perceived as a political statement, The Gods are Pounding My Head! feels more important somehow, more introspective. Perhaps it’s a statement on modern ennui. Since Foreman has declared he’s leaving the theatre to concentrate on film, it’s his s swan song. As Foreman himself says in one of the sound cues, “The action is elsewhere.” As gloriously confusing as any of Foreman’s shows, The Gods are Pounding My Head! indeed chronicles the broken heart of the world.

Given that this may be the last Foreman production to see, his followers won’t want to miss it. 1-16-05

New York Sun, Jeremy McCarter – Arden’s Ideas, Foreman’s Frontiers. One day, scientists say, the intrepid droids prowling around Mars will cease transmitting images of that strange world. We in the theater know how that moment will feel. After 37 years, Richard Foreman has announced he will no longer stage full productions of new plays.

For four decades, the tiny Ontological-Hysteric Theater has been the home of Mr. Foreman’s annual exercise in the metaphysically surreal. (His new departure marks another setback for the once-lively spirit of the East Village: first Joey Ramone, then the Freakatorium, now this.) Like many holdovers from the 1960s avant-garde, Mr. Foreman’s work has been plenty strange, but unlike his downtown contemporaries, he never felt mannered – not in my experience, anyway.

He has lasted so long because of a method no one has mastered so well: He comments on the world we inhabit by exploring the one inside his head. Patterns, symbols, and methods may recur from year to year – the deadpan delivery; the bears, pirates, and baby dolls; the wires across the stage – but each show has felt like a fresh trip into some inexhaustible unknown. Could it be that after four decades we have seen no more of Mr. Foreman’s mental landscape than Spirit and Opportunity have glimpsed of Mars?

If Mr. Foreman isn’t kidding about trading theater for mixed media and film (and Mr. Foreman is a funny man – he may be kidding), then his last show is “The Gods Are Pounding My Head! (AKA Lumberjack Messiah).” In a program he note he calls it a “very elegiac play.” It’s not a way of life that he wishes to mourn, but a way of mind: The old notion that education meant constructing a kind of cathedral of knowledge in your head. Computers, networks, and a civilization turned hasty, he believes, have turned us into “pancake people” – simple, transparent, and thin.

Gone, Mr. Foreman believes, are the heroic geniuses who would, “like lumberjacks,” clear the world of old custom and belief, and create the new. The new play shows us two such lumberjacks, adrift in a world that doesn’t need them anymore. Another casualty of Mr. Foreman’s departure will be the end of the brilliant partnership of Smith & Smith. T. Ryder Smith plays a wry lumberjack with a brogue, who is called Frenchie. He has the air of a Romantic poet fallen on hard times, and doesn’t even perk up when a pair of stone tablets falls into his arms. Jay Smith plays Dutch, a mournful sort of woodsman. He delivers his lines quietly, chin cocked to the ceiling. He is also a large man – much larger than his castmate – which makes him seem a sensitive lug, in the Gandolfini mode.

Gnomic symbols abound: a combination car/locomotive, the heart of the world (it’s the size of a side of beef), Alfred Lord Tennyson. Sometimes the lumberjacks look like the Bruces from Monty Python, at others they seem like Beckett’s Didi and Gogo. (“I’m going to, I’m going to,” is a refrain.) But I like them best when they evoke Hope and Crosby. Their Dorothy Lamour is Charlotta Mohlin, a young Swedish actress whom Mr. Foreman discovered at a lunch counter around the corner. As Maude, she has pale eyes and secrets.

Sure, Dutch and Frenchie will take an ax to the floor and the furniture, but it doesn’t really get them anywhere. Symbols of decay abound. There are skulls on the wall and mushrooms underfoot. Even the playground slide, a major scenic element, was plainly chosen as a metaphor for descent. (Unless it was not chosen as a metaphor for descent, and Mr. Foreman just put it there because it looks cool – it works either way.)

The show doesn’t have quite the coiled power of some of its predecessors. It loses its way, I think, during Frenchie’s soliloquy about turning himself inside out, about mirrors and sunlight. It’s part of the genius of Foreman that even when the writing slips, you may notice another flourish in his meticulously haphazard world. Above the stage hang a handful of birds on the wing. In a play about endings, they bring to mind the dove sent by Noah in search of dry land. Most just hang there, but look again: One of them has a twig. 1-19-05

Newsday, Gordon Cox – What tree-cutters do when the ax falls. A funerary air hangs over the latest offering from avant-garde auteur Richard Foreman. One wall of the playing space is painted black, its arched entrance bordered by black flowers. Dark-painted skulls look down on the stage. A corner is festooned with black pillows, which perhaps wait to cushion the head of a dead king. There is also a lot of plaid flannel. That’s because the subtitle to “The Gods Are Pounding My Head!” is “Lumberjack Messiah,” and its two protagonists are burly ax-wielders. Well, maybe “burly” isn’t the right word, seeing as how one of them wears pearls.

It’s probably no longer accurate to call Foreman’s work experimental. For more than 30 years now, his excursions into the cluttered attic of his own mind have developed recognizable conventions: a jumbled collage of a stage; strings painted to look like dotted lines that create divisions of space; allusive, repetitive dialogue; sudden crashes of dense sound, and Foreman himself overseeing performances from the center of the audience.

Foreman has said that “The Gods Are Pounding My Head!” will be his last stage work before he turns entirely to film and mixed media, which may partially account for its elegiac tone. But the production also mourns a lost time when people were full and complicated beings. Now, as a deep voice intones over loudspeakers, we’re pancake people, wan and flat.Our two lumberjacks, having outlived their “time in the sun,” don’t know what to do with themselves. Sensitive, soft- spoken Dutch (Jay Smith, the one in pearls) questions the state of his world with wide-eyed wariness, while the more jaded Frenchie (T. Ryder Smith, with an Irish accent) accepts his lot with a cocky swagger. Between them ricochets Maude (the mercurial Charlotta Mohlin), a mysterious woman drawn from a Tennyson poem.

There is much talk about the broken heart of the world. There is also a giant, anatomically correct heart pierced by baguettes. Occasionally the stage is invaded by lithe, dark figures clad in billowy pants, round sunglasses and bobbies’ hats topped with jeweled crosses.Even if Foreman’s work isn’t your thing, his shows can produce a weird, mesmeric pull. Sudden moments of recognition – of the lumberjacks’ longing, for instance, or of their claustrophobic fear of the end – can take you by surprise.

Although the show may be an ending for Foreman as well, a stubborn hope remains. The lumberjacks speak of absent gods, but they point bravely ahead, and occasionally break into lovely choral harmony. In spite of the dying world around them, they still have a song in their souls. 2-10-05

NY Press, Alan Lockwood – A black metal contraption bellies out from the rear wall in Richard Foreman’s The Gods Are Pounding My Head! A great stove? It’ll slide and reveal a draped doorway; skulls clog lopped pipes, so the set may be a boiler room. The small steam engine will run its decidedly short track, and mushrooms sprout under an industrial chute, another short run the play’s axe-wielding lead trio will use.

Wherever Foreman’s got us (“a planet moving around the sun” comes up several times), he’s aimed away from today’s most blatant peril: Last year’s King Cowboy Rufus Rules the Universe was Foreman’s traipse into Bushworld. Our reigning avant-garde theater vet keys the more general malaise that’s allowed political travesty; his voice-over chafes that “people were just, you know, thin somehow, just surface only.” Dutch (Jay Smith, who played the daftly threatening Rufus) is its early, strapping locus in a gambit that gravitates audience sympathy amid the restless Foreman omniverse. To rest in one place; is that not to say being easier to upend? Dutch takes and retakes his breath, peering high before speaking—then hits the floorboards like a felled sequoia in Pounding’s largest (but by no means last) fall.

Boon companion Frenchie (T. Ryder Smith), also in tall black boots and a knotted red kerchief, calls down to his pal to “Hang in there, Dutch.” Frenchie’s gaze simmers with defiant melancholy, and when Maude (Charlotta Mohlin) appears, all tensile glances that steel when she’s not cutting them adrift, this expertly played caroming bout of mismatched, sidelong glimpses becomes the galvanizing “dance” on Foreman’s gushing and emptying stage.

The plexi-shields are almost all down since tight, caustic 90s plays like The Mind King and Benita Canova’s gritty quest, and Foreman’s announced that, after decades of his manic, superbly consternating plays, he’s moving to assemble a film bank. If Pounding’s his swansong, its conclusion is fitting tribute: as heartening as it is based on a hopeless quaff, and as visually sumptuous as they come, while going dark, dark, dark…

New Partisan, Cassandra Johnson – Brutal Beauty: Richard Foreman’s Lunatic Attic. Historically, I have been a proscenium girl, and my taste in language has been equally formal: I like poetry. I don’t care if dialogue is naturalistic; I want it to be pretty. Typically, therefore, my goût is for classic or classic-like plays, with stylized dialogue and linguistically challenging, in the SAT sense, word-palates. Verse and poetic theatre more generally demonstrate the beauty of language through language itself, making the ear and imagination actually work and grow, something that naturalism doesn’t demand.

But lately I’ve been discovering the appeal and enlightening potential of theater that destroys language but is similarly unrealistic, stretching ear and imagination through a more violent sort of poetic composition, placing emphasis on visual components, silences, cut off and rearranged words and wordless voices, communicating on a lower frequency.

I had my introduction to Richard Foreman’s work Sunday night and, though it was not what I’d call pleasurable in any traditional sense, it was many other things that art can be: thought provoking, challenging, funny, and highly energetic. The Gods Are Pounding My Head! (AKA Lumberjack Messiah), written, directed, and designed by Foreman, whose Ontological-Hysteric Theatre has for years produced a new play annually at St. Mark’s Church, is said to be Foreman’s last play before committing solely to film.

The set of the play is as much a character as any of the actors. Entering the theatre space one might have been wandering into a lunatic’s attic. Doves hang from the ceiling, while skulls emerge from long industrial cylinders set on one of the walls; a sort of Gothic or fairy tale tower serves as a moving set piece and up-stage center entrance for the actors, while gymnastic rings hang from pulleys attached to sand bags, next to a slide. The central set piece is a small train (a symbol of dubious progress?) poised on tracks, and which is variously ridden, pushed, beaten and humped by the three characters: the lumberjacks Dutch (Jay Smith) and Frenchie (T.Ryder Smith), and Maude, the sad-wild temptress whom they both desire.

I read Forman’s lumberjacks —who cut down, but plant no seed, and who in the end suffer the most — to be a metaphor for nihilists who destroy traditions and belief-systems without erecting anything in their place. Maude (played with striking intensity by the uniquely beautiful Charlotta Mohlin) is the very symbol of deranged and abused beauty. The principal characters are supported by a demonic swarm of highly choreographed and identical ensemble actors. By turns the three main performers act out their own horrors and fantasies and those of the other two, while the ensemble embellishes their tales with twisted musical-like dance numbers. In an incomprehensibly obscure unfolding of non-events, a mise en abîme of metaphor, the common ground seems to be that each set piece and every image is a perversion of the pure or childlike. No matter how innocent, the objects — flowers even — are painted black, to look like a playground or a garden after an eruption, or perhaps a bombing.

The language of Foreman’s play parallels its visual construction. His characters are childlike, attempting to understand concepts, to formulate thoughts and questions, but never find quite the right words. Lumberjack Dutch repeatedly stammers, “Sup-pose I were to p-postulate,” only to be interrupted again and again by Frenchie or another voice. Maude communicates in high-pitched, piercing shrieks as often as with words. In retrospect, they seem unbearably sad and empty, two-dimensional. They occasionally break out into nursery rhyme, repeating “snug as a bug in a rug,” among other songs, over and over again. They long to be “snug” again, like children. The voice on the god-mike chants “Tendency…Tendency.” Is Foreman decrying habit, or do we need “tendency” in our lives?

I found Gods to be more interesting for having had read the author-director’s brief note just before the start, without which I — a Foreman neophyte — could neither have understood as well, nor gleaned as much from, the play itself. This begs the question: Should the success of a work of art rely upon supplementary, biographical information from or about its creator? Isn’t that cheating? Either a work of art is beautiful, interesting, edifying, or enjoyable, or it is not. Shouldn’t it speak for itself?

Still, if it improves the experience, explanation has its merits. Foreman writes, “…today I see within us all… the replacement of complex inner density with a new kind of self — evolving under the pressure of information overload and the technology of the ‘instantly available.’ A new self that needs to contain less and less of an inner repertory of dense cultural inheritance.” He goes on to discuss the “pancake people” who are often brought up in the play. These “thin” sorts of people know many things, but know few things very well. Instead of being connected to human beings over time through the truth of “humanness,” emerging from the past and giving birth to the future, they connect to humans over space, thinly and loosely, belonging only to one cold moment.

The play’s overall feel may be coldly Germanic, but the questions it raises are heated and valuable: Are people today better off for knowing more? For having more? When basic things — eating, sleeping, copulating, even communicating — are so easy, how can they be as valuable as when they took time and effort, sacrifice? Gods linger over the tension between man’s primitive hunger for food and sex and his desire, as Aristotle has it, “to stretch himself out towards knowing.”

This tension informs the irony of an experimental artist nostalgic for tradition, putting on a little nightmarish and wishful play, a diaspora of language and images, that longs for simplicity, order, and ritual. Perhaps it takes such unpleasant images, such a headache of flashing lights, voiceovers, screams and word fragments, running around and grotesque, truly ugly things to remind us of what we sincerely find to be life’s beauties.

A few of Gods’ most powerful moments came in the midst of the actors behaving like madmen in a bad dream, as when notes of Beethoven rise loftily to submerge the chaos. The music’s absolute, objective beauty spooks up from the culturally dense past into the mess unfolding on stage, the contrast highlighting the garishness of the characters’ experience, which I fear is a representation of our own experience. At another moment the voiceover satirically pines, “As the Victorian poet Alfred Lord Tennyson wrote…” and then one of the lumberjacks interrupts to quote, “Come into the garden, Maud, For the black bat, Night, has flown, Come into the garden, Maud, I am here at the gate alone.” The lyrical beauty of Tennyson’s words JUMP out from the play’s dissatisfying and brutal language, which throughout seems to scratch the ear’s record.

A lunatic’s attic, the inside of man’s thought muddled brain, a representation of the world, or some other strange place, Foreman’s stage world was strangely beautiful: entertaining in the circus way, moving in the dark way, edifying in the ironic way, funny in the absurd way, and overall a very well done piece of radically abstract art. Its unity and sense are not immediately detectable; we have to work to find them. And in my experience the play’s images have grown even more interesting through my reflections of the last few days.

But they fail to resolve. Foreman is anguished to see man numbed and immobilized by an excess of information and choices, genuine human connectedness jeopardized by a surfeit of petty knowledge, to the detriment of profound understanding. But he offers no way out of this circumstance. Is art the cultural time-machine that could recreate such depth, by focusing on the perennial and the individual through philosophy, rather than the ephemeral and distant through technology and the news? Or is it merely a way of representing our helpless condition? Foreman doesn’t seem to be telling.

Upon leaving St. Mark’s church Sunday night, the relative normalcy of New York’s unusually warm city streets (as compared to the inside of Foreman’s head made manifest within the church) was shocking — I had trouble navigating space in the linear, real world, so much had Foreman’s sucked me in and rearranged my sense-perceptions. For all its seeming chaos and motley symbolism (Dali meets Pollack) there was a sad and steady current flowing beneath the uneven surface of the play; I felt distinctly melancholic and was at pains to unearth what might be Foreman’s hope. Perhaps it is in the existence of the play itself. 02.12.2005

[previous] [next]