Excerpts from the reviews

Full reviews are below

“The most important, rewarding, nourishing show that I’ve seen all season . . . A mystery story about understanding a life . . . An extraordinary journey – via a one-man show disguised as lecture – toward spiritual renewal . . . A Dutch librarian – nearing middle age, alone and a little sad, a lot resigned – happens upon an unusual book in the course of his duties: a 19th-century travel guide . . . 113 years overdue . . . He tries to find out how this book wound up in his slot and – more important – who left it there. . . A gorgeous, unforgettable tale . . . Berger’s text is dazzlingly rich and deliciously engrossing . . . T. Ryder Smith does remarkable work here, characterized by enormous honesty and conviction . . The most profoundly moving and wise play on stage in New York right now. “ Martin Denton, nytheatre.com

“Literate and enchanting . . . What begins as Pythonesque highbrow silliness turns into an existential detective story. . . . T. Ryder Smith’s gaunt handsomeness and gravity make him transfixing onstage. . . . Altogether, Berger’s eloquent script and Smith’s rendering make ‘Lintel’ solo storytelling of the highest caliber “ David Cote, TimeOut NY

“It hardly slacks . . . T. Ryder Smith, hair powdered and face contorted with fastidiousness and fanaticism, plays the Librarian with verve. . . His beatific expression as he coerces his limbs into a jerky eloquence is hilarious and affecting.“ Alexis Soloski, The Village Voice

“Both a funny tale of a Dutch librarian’s midlife crisis, and a serious, intriguing look at the value of any one life. The play is certainly, as billed, ‘An Impressive Presentation of Lovely Evidences’.” The New Yorker

“A tale of a picaresque journey that evolves into a spiritual quest. . . A wonderful metaphor for life’s elusive but inextinguishable meaning.” Bruce Weber, The New York Times

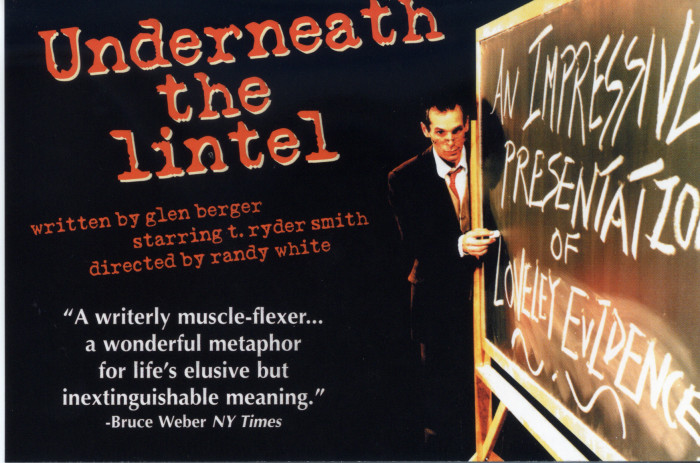

Publicity

Full reviews

Time Out NY, David Cote – In architectural parlance, the lintel is the horizontal support structure over a doorway: Underneath one is where you should stand during an earthquake; it’s also where you hang a mezuzah. These facts are only tangentially material to Glenn Berger’s literate and enchanting one-man show, Underneath the Lintel, but they’re worth mentioning, lest the odd title seem off-putting. Lintels do figure into the story, as very significant thresholds where life-changing choices are made. At any rate, if you enjoy the tricky intellectual fiction of Jorge Luis Borges or the dark surrealism of Mikhail Bulgakov, this erudite adventure will make a satisfying diversion.

The evening is framed as a presentation of “lovely evidences” by a librarian (T. Ryder Smith) from Hoofddorp, Holland, who, we learn, has rented the very theater we’re sitting in to tell his story. A meek, shabby fellow of questionable authority (not to mention sanity), he tells us that he once discovered in the overnight slot a book that was 113 years overdue. Determined to make the offender pay “a pretty fine,” our hero recalls his efforts to track him down. As he does, he pulls out neatly tagged pieces of evidence to corroborate each plot twist. It turns out that the perpetrator left a record of his movements that span continents and—impossibly—centuries (laundry ticket in Victorian London; address of a post-office box in 20th-century China).

Without giving too much away, what begins as Pythonesque highbrow silliness turns into an existential detective story with creepy biblical roots. At bottom, the librarian’s obsession has more to do with fear of mortality and the vicissitudes of history. In a quirky yet resonant metaphor characteristic of Berger’s clever script, we are all crickets smothered in dustballs behind couches, destined to be forgotten. “In 1887 in Honan, China,” the librarian tells us, fiddling with his date stamper, “a flood drowned 3 million people! And no one in Hoofddorp batted an eye at that either, so the crickets behind the couches shouldn’t take it personally. If it isn’t someone you know, then it’s all just behind the couch.”

Smith should watch out that he doesn’t gain a reputation as the “secret history” actor. Last season, he was the best thing about Lipstick Traces, adapted from Greil Marcus’s speculative history of anarchist culture from medieval heretics to ’70s punk. His gaunt handsomeness and gravity make him transfixing onstage—no matter how far-fetched the premise. Moreover, he humanizes this petty bureaucratic character, who might otherwise come off as a crackpot. Altogether, Berger’s eloquent script and Smith’s rendering make Lintel solo storytelling of the highest caliber. 11-1-01

New York Times, Bruce Weber – A Librarian as a Sleuth in Hot Pursuit. ”Underneath the Lintel,” a monologue by Glen Berger that opened at the SoHo Playhouse yesterday, is the kind of piece that works harder to be winning than it does to be heartfelt or original.

A tale of a picaresque journey that evolves into a spiritual quest, it is, as a script, a writerly muscle-flexer, one in which you can imagine the playwright applying charm and erudition to the narrative as though he were following a recipe for audience-pleasing. And as a vehicle for the performer, in this case T. Ryder Smith, it is a chance to play around with a trove of actorly tools.

Mr. Smith plays a Dutch librarian, a fussbudget with the personality tics of the shy, small-minded and eccentric, a man whose life’s focus is making sure no one tries to get away with leaving overdue books in the library’s overnight return bin.

Or at least it was his focus until some months before the action of the play begins, when he found a book in the bin — a weather-beaten Baedeker — that had been checked out 113 years earlier. Ever since then he’s been on a quixotic and around-the-world search for the returner — and the borrower — of the book, and the results are of enough import that he has arranged to deliver his findings in a public lecture. Thus the play; with the aid of a blackboard, a screen for slide projections and a chest containing scraps of evidence, the librarian, with increasing agitation, tells his story.

There is something innately compelling in this construct, the unlikely discoverer of a secret thread who is instinctively moved to pull it and pursue the consequent unraveling. What is unraveled here is a mystery that dates to the Crucifixion.

In the service of his very good idea, Mr. Berger has taken great pains to make the journey tortuous: the librarian follows clues — the first, left in 1913 as a bookmark in the Baedeker, is a yellowed claim check from a London dry cleaner — that lead him to a post office box in Dingtao, China; a government records bureau in Bonn; a sound and photo archive in New York; and an attic in Australia.

That all these plot points are peculiar and obscure is part of the point. The logical connections made by the librarian are meant to be a little ridiculous, testament to an inspired obsession that, by the end, assumes the character of faith. And all of this makes you want the play ultimately to be better than it is.

The problem is that Mr. Berger’s gift is almost entirely in his craft. He makes all the right moves, pacing the narrative with aha! moments and comic asides, providing interesting historical tidbits when necessary (we learn, for example, about the fox hunters’ habit of plugging up the fox’s lair the night before the hunt, a practice known as earthstopping), and gradually deepening the librarian’s self-awareness as he becomes an Everyman, equally moved by the agony and ecstasy of existence.

He has even found a wonderful metaphor for life’s elusive but inextinguishable meaning: the character of the wandering Jew, the shopkeeper who, from underneath the lintel of his shop, chased Jesus from his doorstep and was doomed to deathlessness and obscurity.

But finally, the playwright’s ingenuity never ferries the audience into unexplored territory. That the experience of life on earth is characterized by a desperate attempt to leave a mark, that mortality makes every second valuable, that love is our only available salve — these are the various strains of the playwright’s message here, and they are delivered without any individuated nuance. They’re canned themes.

The librarian is a bit of a canned character himself. He is equipped with a number of tried-and-true qualities, including the neat-but-tattered wardrobe, the meticulously earnest argumentativeness and the self-importance that comes with living in a circumscribed world. (He carries his book stamper with him, on a chain around his neck, claiming pompously that every date in history is within it.) One result of this is that the injected humor usually feels as though it’s from a textbook.

Mr. Smith’s performance is fully immersed in the stereotype. He speaks with a slight accent (Dutch, I guess), dodders self-deprecatingly and nervously at the beginning and grows increasingly insistent and desperate as the show proceeds. He is skillful and not unengaging, but like the playwright, he seems to be deploying his skill more for exercise than anything else. 10-24-01

CurtainUp, Macey Levin – The Librarian is a little man living a simple existence until the discovery of a book leads him to explore history, faith, the place of man in the universe and his own existence in Glen Berger’s compelling drama Underneath the Lintel playing at the Soho Playhouse. While checking books deposited in the overnight slot at the library in Holland where he is employed, the Librarian (he is never given a name) finds a book that is 113 years overdue. Because of his sense of responsibility, he sends a notice for the money owed the library to an address he ferrets out from old records.

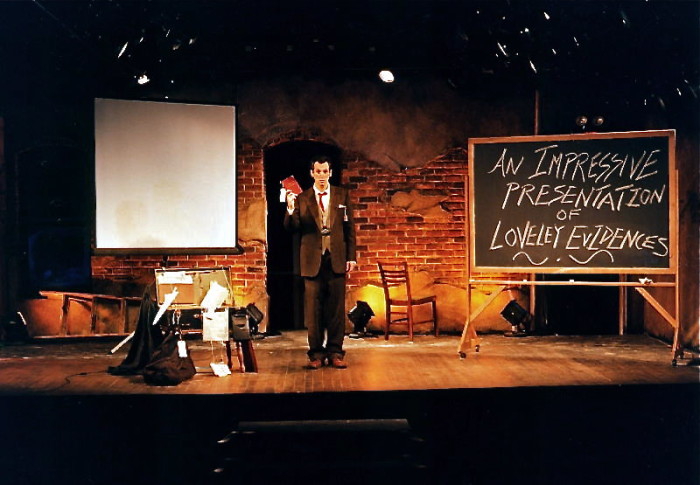

As the evening begins, we are offered a lecture relating his experiences using a chalkboard, a slide presentation and a trunk that holds the evidence of his story. Standing in his tattered clothes and scuffed shoes, in need of a shave, he appears to be merely another self-absorbed eccentric with a tale he feels is important to be told.

As he gathers scraps of information, the Librarian, who has never left his small town, traverses the earth in search of answers to the cryptic messages that unfold. His journey reveals truths and opens ageless questions that compel him to go forward. While confronting the cosmic significance of his quest he is forced to reflect on the barren world of his own life. Now, however, he has a reason to go on, not only for the benefit of mankind but for his own sense of being.

T. Ryder Smith stars in this one-man play and stirs the audience with a sensitive and nuanced performance. As the mystery unwinds and becomes more significant, the intensity in Smith’s manner deepens and the Librarian’s obsession takes on layers of humanity and integrity. Smith is so convincing that when he sheds tears and hides from the audience, we feel uncomfortable to be witnessing such an intimate reaction to life.

This is not performance art where an actor appears in front of an audience and throws out his opinions and attitudes in a frenzy of self-indulgence. It is, rather, a well-written play with a structure, sub-plots and meaningful thematic elements that stimulate reflection and discussion. The Librarian is a fully developed character the audience can understand despite his myriad idiosyncrasies. Berger’s play is dramatic literature of the finest import.

Directed by Randy White, Underneath the Lintel draws the audience into the Librarian’s life with humor and urgency. The staging of the play is clean and understated, allowing actor and director to use the playwright’s words to generate the emotional impact of the plot. White’s pacing of the drama builds subtly until the audience embraces the Librarian’s cause and is fascinated by his search. His life becomes our concern.

Lauren Helpern’s set design utilizes the configuration of the theatre’s stage while making it feel bare and unsightly, very much like the Librarian’s world and life. The effective lighting design by Tyler Micoleau is dramatic and appropriate in its simplicity.

Underneath the Lintel is a small play confronting profound ideas in a theatrical experience of immeasurable stimulation and satisfaction. 12-7-01

Offoffoff.com, Joshua Tanzer – Seek and you shall fine. You really have to see “Underneath the Lintel.” And that’s not just me talking — there’s also a certain Dutchman with something urgent to tell you and has been trying to get your attention for some time. You would have seen the posters for this very important event if the Dutchman involved were not, well, a librarian.

“I put up signs,” insists the mild-mannered gentleman in his frayed tweed jacket, lumpy sweater vest and conservative tie. “But as soon as I turned away they were covered with other signs.”

“Mine were nicer,” he laments

The mystery of “Underneath the Lintel” starts with the most shocking of library offenses: a book returned 123 years overdue. And returned in the overnight slot, no less! The Librarian sets out to levy the fine of his career, but the trail leads him on a worldwide pursuit toward a conclusion that he would never have imagined.

Which is why he’s arrived in New York with a suitcase full of clues ranging from ancient documents to the suspect’s pants, desperate to tell his story.

A few years ago, playwright Glen Berger presented another terrific, understatedly funny show at the Currican Theater called “Great Men of Science Nos. 21 and 22,” about two fictional 18th-century scientists who pursued their somewhat misguided research more out of obsession than actual talent. The Librarian of “Underneath the Lintel” is a similar character. Never a leading intellect, even within his little town, he has nonetheless pursued his self-appointed mission singlemindedly, maybe because it’s his destiny. He is one of the meek who knows he won’t inherit the earth but has somehow found one tiny corner of it that he can call his own because nobody else has thought to go there.

There’s a lot of humor in “Underneath the Lintel,” much of it related to the repeated shock of discovery by the milquetoasty protagonist, who’s played to perfection by T. Ryder Smith. He recounts his cunning plan to get time off of work to continue his investigation by calling in sick, even though he isn’t; nobody has ever thought to do this before, he says with amazement, or at least no librarian has.

If the play constantly pokes fun at its librarian hero, it does so with total affection. Underneath the humor is the playwright’s vision of humanity, if it’s not too grandiose to call it that. What Berger finds in these characters of his — the obsessed scientists in the earlier play, the world-traveling librarian here — is a passion for life that they pursue, even to the point of self-destruction, because our drive to discover and to leave even the smallest mark on the world is what defines us as people. The play itself, like its protagonist, starts out modest and amusing and winds up discovering meaning of cosmic significance. 10-26-01

nytheatre.com, Martin Denton – Part of the fun of my job is that every night is a crapshoot: the nature of theatre is that you can never know in advance which play or musical is going to be the one that resonates, that strikes the chord, that reveals something fresh and wonderful and true. So it was with Glen Berger’s Underneath the Lintel, which I attended, several weeks after its opening, with no expectations whatsoever. It turned out to be the most important, rewarding, nourishing show that I’ve seen all season.

Underneath the Lintel is a mystery story about understanding a life: gathering the debris left behind by a human being and filling in the gaps to try to make sense of the time that that human spent on this planet. Underneath the Lintel is also an extraordinary journey–via a one-man show disguised as a lecture–toward spiritual renewal. “Would you know a miracle if you saw one?” asks the play’s narrator and central character. Sometimes just waking up to the wonders and mysteries of life is all the miracle we need.

I want you to see Underneath the Lintel as soon as possible, so I’m not going to give too much of it away right now. A Dutch librarian–nearing middle age; alone and a little sad; a lot resigned–happens upon an unusual book in the course of his duties one day. It’s a tattered old copy of a 19th century European travel guide; the strange thing is that it is 113 years overdue.

Lucky for us, our hero does recognize a miracle when he sees one: his curiosity aroused, he tries to figure out how the book happened to show up in the return slot and–more important–who left it there. As he searches for clues to the borrower’s identity, he finds himself drawn into a compelling and puzzling conundrum. His efforts to crack the case take him to England, China, and various other unexpected places, and eventually lead to a surprising conclusion that tests his faith in the unbelievable and unknowable.

It’s a gorgeous, unforgettable tale that affirms the tenacity and endurance of man in a universe that feels infinite even when we don’t stop to think about it. The librarian tells us that he is talking to us today in order to prove one life and justify another, and that’s exactly what he does. Human contact–whether tentative or long-lasting–is only one of the miracles waiting for us in Underneath the Lintel.

Berger’s text is dazzlingly rich and deliciously engrossing: the narrative flies and before you’re aware of it you’re drawn into the librarian’s extraordinary saga. T. Ryder Smith, the play’s lone actor, does remarkable work here, characterized by enormous honesty and conviction. Director Randy White lets neither pacing nor interest lag. Costume designer Miranda Hoffman has dressed Smith in a homely suit that tells us an enormous amount about the librarian before he even begins speaking. Set designer Lauren Halpern and lighting designer Tyler Micoleau provide an appropriate environment for the piece; sound designer Paul Adams works some miracles of his own (but you’ll have to see the play to discover their exact nature).

Underneath the Lintel, so simple and unassuming, is the most profoundly moving and wise play on stage in New York right now. Aren’t you curious about what secrets lie behind a 113-year-old book? You should be…

Village Voice, Alexis Soloski – One Fine Day. On an inauspicious morning at a Dutch library, a librarian makes an unexpected find in the overnight return box. The pantheon of book-borrowing sins holds no precedent for the box’s contents: a much mistreated Baedeker’s guidebook 123 years overdue. Even without compound interest, this tardiness merits a tidy fine, and in Underneath the Lintel (Soho Playhouse), playwright Glen Berger’s latest, our librarian hero determines to track down the miscreant. After many international adventures, he hires a theater for one night, to offer “an impressive presentation of lovely evidences” detailing his quest.

Berger’s monologue, subtitled The Mystery of the Abandoned Trousers, hardly slacks. Mailing a fine to the long-lived scofflaw in question proves difficult, as the borrower listed his name only as “A.” In an effort to run him to earth, the librarian, who has never left his native town of Hoofddorp, zips to China, Australia, Germany, and America. He eats sweets, greases palms, sees Les Miserables in three languages, and fritters away all his accumulated vacation days. He has the time of his life, or, perhaps, for the first time actually has a life.

T. Ryder Smith, hair powdered and face contorted with fastidiousness and fanaticism, plays the librarian with verve. He shuffles about the stage in a ragged coat, caressing the date stamper around his neck, proudly displaying his exhibits, and speaking in a bizarre accent—purportedly Dutch. Under Randy White’s direction, these mannerisms and characteristics never quite add up to a fully realized character, but this is never as bothersome as it ought to be.

You might say something similar of Berger’s play. His tendencies toward sentimentality and occasional cutesy cleverness mar the play, but never terribly. Troubles arise toward the end when the librarian, having identified his quarry, indulges in some metaphysical speculation and pointing up of metaphor. This heavy-handedness doesn’t intrude too much on the play’s good-naturedness. Yet you can’t help wishing Berger would lighten up and include more scenes like the one in which the librarian goes swing dancing in New York. Ryder’s beatific expression as he coerces his limbs into a jerky elegance is hilarious and affecting. These are the best scenes, when the librarian, so desperate for a thread of A.’s life, unexpectedly discovers the fabric of his own.

Backstage, Leonard Jacobs – Glen Berger’s “Underneath the Lintel” is quirky; its restless heart renders it endearing. The story of a librarian (T. Ryder Smith) who stumbles upon a book 113 years overdue is practically David Ivesian; Berger’s play, however, reveals a humanitarian voice.

You can see it early on, with the librarian’s controlled but palpable outrage—that is, if you can imagine the indignant outrage of a Dutch librarian who has rarely, if ever, ventured from his comfortable perch or familiar hamlet. You can see it later as the librarian commences a whirlwind, worldwide journey to reconstruct the epic story behind this violation of borrowing privileges—ludicrous, yes, but just absurd enough to work. That the book in question is a Baedeker’s Travel Guide is a wonderfully metaphorical idea.

In lecture format (the blackboard reads “An Impressive Presentation of Lovely Evidences”), the librarian presents carefully labeled scraps of evidence from his search. Scrap by scrap, playwright and actor make merry with baffling, obtuse plot points in what becomes a rollicking, bewildering orgy of minutiae and arcana. Director Randy White brings a naturalistic serenity to his staging, sanding down the rougher moments and playing each beat with a maestro’s precision. Berger’s play, in the end, may more neatly fit the contours of an extended skit than an 80-minute jaunt around the world, but it works nonetheless.

A versatile Off-Off-Broadway fixture, Smith makes a marvelous librarian; he refuses to devolve into caricature, the natural trap. As he hunts down the history of book and borrower—visiting Germany, London, New York, Sydney, even China—watching him portray a man whose horizons become ever so slowly broadened is one the production’s salient pleasures. Watching him learn the truth behind the tale is another.

Lauren Helpern’s set—pieces, really—are often very amusing. Tyler Micoleau’s gentle lighting and Paul Adams’ sound design smartly address the particular needs of this rather peculiar play.

Greenwich Village Gazette, Arlene McKanic – As she watched Underneath the Lintel, Glen Berger’s play about the stubborn and sometimes desperate attempt of human beings to leave something of their mark in the world, she couldn’t help but think that she knew a least two people who lost people in the World Trade Center catastrophe. Memorial services had been held, but there were no bodies to bury — only the memories of their loved ones and whatever inconsequential stuff they’d left behind were proof that the people had existed at all. This is also true of the mystery library patron who haunts the life of Berger’s nameless Dutch librarian, played by T. Ryder Smith.

The play begins in 1986 when the librarian, who’s rented a run down old hall, is lecturing about the identity of a mystery patron. One day he found a chewed up old Baedecker in his library’s overnight slot. The book was not only late, but was due back in 1873. His sense of propriety insulted, the librarian sets out find the culprit and collect the overdue fees; the amount this is going to come to nearly has him salivating with glee. But his investigations lead him to an intriguing but impossible conclusion: the person who returned the book and who identified himself only as A., is possibly the same person who borrowed it in the first place. The theorem quickly consumes the intensely anal librarian, whose search leads him literally around the world and ultimately to unemployment. On the way he discovers a stub for an unclaimed pair of trousers from a Chinese laundry in London, the quarantine records for a dog named Zebrina (a clue to the person’s identity) and a mystery woman. At the end there’s no body, only scraps from a life, an eerie recording of what might be the patron’s voice, and the librarian’s awe at his ability to leave traces of his existence, to claim, almost defiantly, “I was here.”

T. Ryder Smith is wonderful as the somewhat cracked librarian. Tall and gaunt in his moth eaten jacket and somewhat shiny trousers (care of costume designer Miranda Hoffman) with wild hair and haunted eyes, he seems a cross between Arthur Miller and a broken down Ben Stiller. Under Randy White’s capable direction, the librarian’s obsession with the elusive patron moves from hilarious to deeply moving. Lauren Helpern’s set design, with its crumbly brick walls, projector screen, chalk board and junk, resembles a rubbishy attic in an old school, while Tyler Micoleau’s lighting is direct and simple. The props are perfect. The ticket stubs and manifests seem genuinely marked by time, the mystery man’s ancient trousers are full of holes, the cardboard suitcase where the librarian keeps his evidence seems precarious, but the most emblematic object is the librarian’s stamper, the one thing he insisted on keeping from his old job. The stamper has every date that ever was and will be, and so contains the date of everyone’s birth and the date of everyone’s death, forever. It’s one of the little things in Underneath the Lintel — the title refers to where the library patron was standing when he committed a huge social gaffe — that gives one delicious chills.

Thought provoking and unfortunately timely, Underneath the Lintel, whose previews were postponed due to the disaster, was presented by the Soho Playhouse, 15 Vandam Street.

Time Out NY, David Cote – Second Looks: Underneath the Lintel. Author Glenn Berger is currently starring in his own one-man show until the producers can find a replacement; he will act in Underneath the Lintel for at least a month. That’s good news and bad. On the one hand, Berger is sprightly and comic as the eloquent Dutch librarian drawn into an occult conspiracy that involves a library book 123 years overdue, traced back to an apocryphal biblical figure. The evening is structured as the disheveled and possibly insane fellow’s public presentation of several “impressive evidences.” Berger gets many laughs, but his control of Lintel’s wild, sorrowful undercurrent (a Beckettian lament for life’s flimsiness) is weak. T. Ryder Smith tore into the 90-minute monologue when it opened a year ago, and the effect of the librarian’s quest was both hair-raising and tear-jerking. Berger’s solo remains a rich entertainment, but let’s hope the producers can find a talent comparable to Ryder’s. 7-4-01

(The Journals of Mihail Sebastian By David Auburn. Dir. Carl Forsman. With Stephen Kunken. 45th Street Theater.

Time Out NY, David Cote – There are two ways to pull off a one-person show. Either you’re a rock-star actor, such as T. Ryder Smith in Underneath the Lintel a couple of years ago, and you can fill two hours with your unique presence alone. Or you’re a nimble mimic (see Jefferson Mays in I Am My Own Wife), able to beguile an audience with a gallery of crisp characters to create the illusion of a full cast. Neither is the case with Stephen Kunken in David Auburn’s well-intentioned but leaden The Journals of Mihail Sebastian, a first-person account of Romania during World War II. Kunken is quite likable, but both he and his material—in which an earnest narrator bears witness to terrible times—never justify their existence outside of the History Channel.

Adapted by Auburn from Sebastian’s recently translated journals, the events of the play detail the grim erosion of Jewish Romanians’ civil liberties by a succession of anti-Semitic governments, and the dreadful march of Hitler’s forces east. Sebastian (1907–1945), a Jewish playwright whose bright career was stalled by racism, became an unusually prescient and conscientious chronicler of his times in his diaries. Kunken plays him as a thoughtful, charming and soulful young man anguished by his own impotence. Why Auburn, who had a bona fide Broadway hit and awards-magnet with his smart, polished math drama, Proof, should turn in this direction is hard to fathom. Perhaps, reading about a young playwright not so unlike himself, but on the boot end of history, he felt a prick of conscience. At any rate, we’ll have to wait for the journals of David Auburn to get the real story.)

Footnote

Portland Center Stage’s Director of Literary and Education Programs, Mead Hunter, recently badgered the reclusive Glen Berger into talking about how he came to write Underneath the Lintel, a play that’s been described as “a metaphysical detective story.”

MH: Whereas O Lovely Glowworm took over a decade to morph and meander and evolve into the form we saw last spring here at PCS, you’ve said that Underneath the Lintel came spilling out of you all at once, in a rush. What was it about this story that demanded that you give voice to it?

GB: Well actually, all my plays begin with that same damn demand “to be given voice.” The next step in my process is to say with great deluded confidence to that demand, “yes! I will give you voice! And this time, it’ll all come out in a rush! I see it so clearly.” Step Three is to bask in the anticipation of an easy writing assignment. Step Four is to figure out just how to turn the demand into something tangible, something that can be presented. How do we display the tale? With wall brackets? On a plinth? A clothes hanger? It’s all trial and error, and it’s almost invariably the very last pair of pants in the store that fits. By sheer luck alone, I hit upon a workable framework for Underneath the Lintel a little earlier in the process than usual. It was luck. Sheer luck.

MH: I understand that the earliest performances of the play took place in a downstairs cabaret club and that its central character, the Librarian, was played by none other than Glen Berger. Was it hard later on to turn the role over to other performers? And did the play change as a result of their contributions?

GB: I had originally written the piece for the Yale Summer Cabaret (my friend and colleague Wier Harman was the curator). I was writing all the way up to the deadline and knew that no actor other than the author would have enough time to memorize an hour and a quarter of material so quickly. So I wrote the first draft playing to my very limited performing strengths, and made certain choices such as making the Librarian a man wholly ill-suited for the task at hand and quite nervous about his upcoming presentation. I also made the decision, as actor, to completely ignore the writer’s request that the Librarian have a Dutch accent, even though, as writer, I had anticipated the actor’s difficulty with accents and decided Dutch was the best option, as many of the Dutch people I know have excellent English with just a little something untraceable added to it. I thought I could at least do that. I couldn’t.

So, when T. Ryder Smith (the first Librarian in the Off-Broadway production) came in to audition for the role, I was immediately staggered by the authenticity and seriousness he brought to the character. I could truly believe he was a librarian from Holland, and my perception of the play permanently changed in those first audition moments. I felt a renewed obligation to make sure this fellow was as fully realized a character as the piece could take.

MH: No doubt you were present for some of those subsequent productions. When you’re there in rehearsals, do you find that the actor tends to do an unconscious impression of… you?

GB: No. They do, however, do conscious impressions of me behind my back.

MH: Like many of your characters, the Librarian speaks with an offbeat syntax that is idiosyncratic; he seems quaint, not quite of our time. Did you have a model for his quirky speech patterns, or is he just fluent in Bergerish?

GB: Idiolect is a great word — defined as the individual’s personal and unique way of using language. I wanted a “not-quite-of-our-time” quality to the Librarian’s way of speaking if only because I wanted the Librarian to seem more and more like the object of his pursuit, a fairly “out-of-time” person himself.

And, yes, there’s one particular ancient recording of the music hall performer Dan Leno from 1904 that has him playing a Beefeater giving a tour of the Tower of London to a gaggle of old ladies, and unable to keep his tour on track because he’s constantly distracted by “the refreshment room.” Leno’s cadences have left an indelible impression on me, affecting even some of the Goat’s speech patterns in O Lovely Glowworm. So he’s at least one influence. And “the unreliable tour guide” seemed an appropriate model for the Librarian character. I even appropriated the Beefeater’s “Still. We’ll Proceed,” and made it the Librarian’s phrase of choice — not only as an utterance to get himself back on track, but, by the end of the play, as a more existential declaration, speaking of himself and all humanity.

MH: It’s amusing that the Librarian’s tale begins with his outrage over a travel guide returned 113 years overdue, and then he goes on an international trek of his own, virtually creating his own travelogue. Is there personal significance, for you, in the various places the Librarian visits during his search?

GB: The specific places? No. But when I first moved to NYC from Seattle, I worked as an assistant editor at Fodor’s Travel Guides for a year. One of my jobs was sorting through the mail sent in by satisfied or annoyed users of the Guides — annoyed because certain details of the books were out of date and they wasted precious vacation time heading to a restaurant that went out of business years ago. For some reason, the idea that every detail in those books would in time be out of date (either the location of a particular shop, or, due to continental drift, the location of the entire country), always moved me. In one of the Fodor’s conference rooms was a shelf of Travel Guides going back some 60 years or so, and I began to wonder at all the places listed in those earlier guides that were no longer around. What would it be like to go on a trip with an absurdly out-of-date travel guide? It would be a trip of ghosts. It would be haunting and profound I don’t doubt it. When opening those letters written to Fodor’s, I’d sometimes pretend that I was about to open a letter written by an impossibly ancient and ticked-off user of the guides recommending various restaurants to include in the book that haven’t existed for 200 years. I would pretend this because it simultaneously made me chuckle and gave me the shivers, and also because my job was often pretty boring. Either way, it was one of the germs for Lintel.

MH: In the play, you take a European myth that was originally anti-Semitic and you recuperate it, in a way… you transmute it into something pro-human. But I bet this has left you open to criticism from both Jews and Christians alike. Have you had to answer for this, and how have you coped with it?

GB: Yes, there have been letters from Jews calling me anti-Semitic and letters from Christians calling me a Jesus-hater, and it’s also been noted in letters that I must be pro-Zionist, and still other letters calling me oddly evangelical for someone with a Jewish name like Berger, and I honestly loved, really loved and dug the fact that I received letters at all, because it gave me a chance to enter into dialogue with the audience, and that’s why I write these things in the first place. I finally fashioned a rather lengthy standard response to the letters and it wound up becoming the prototype for the afterword to the published version of the play (available through Broadway Play Publishing). It’s very lengthy, and perhaps PCS will print it in their study guide. The short answer is: “the play isn’t about Christianity or Judaism but thanks for writing.”

The play was inspired in part by early klezmer recordings, and the desire to present the “jewish spirit” as I see it (and feel it) was one of the original impetuses for writing the play. The success of at least this dimension of the work was confirmed by the New York Jewish weekly, The Forward, whose reviewer enjoyed the Jewish spirit of the play, but only after seeing it a second time — the first time having left the play in a huff, fuming over its “anti-Semitism.” Apparently a different performer made all the difference for her. I suppose it’s just Lintel”s cross to bear.

MH: Now Portland has seen two Berger plays in one year. The Goat in Glowworm and the Librarian in Lintel both construct meaning out of the clues — real or imagined — that they find around them. Are you saying that this is what consciousness does — imbue life with meaning?

GB: Um, I suppose I am. I mean, what is meaning, at the end of the day? Meaning and Context are synonymous, really. The better our understanding of where and how we fit in, the more meaningful our lives become. In short, we find meaning in relationship. Our relationship to ourselves, our family, our community, nation, to art, to history, to earth with its 100 million other species, the universe, and All That is Beyond. It’s the disconnected one who finds life meaningless. Both The Goat and the Librarian do the best they can to incorporate themselves into the larger picture. Perhaps the clues are imagined ones, but the clues are just the launching pad to send them to their very real epiphany, and when it comes, the clues and evidence are no longer needed.

MH: Don’t answer this if you don’t want to, but… you’ve written that the title of Underneath the Lintel is a double-entendre — a verbal pun of sorts. In one way it refers to the existential dilemma of the human condition. But what is the other sense?

GB: So The First Sense, to be clear — Our Librarian and the Librarian’s Quarry each once made a choice and/or committed an irreversible act “underneath the lintel” — a choice that would haunt the rest of their lives. We each have such moments in our lives where the choice to “do the right thing” is presented to us, though we often become aware of the magnitude of the choice only in hindsight. This is the first sense of the title, as it asks the question, “To what end, a Life, if it’s punctuated with these maddeningly irreversible decisions?”

For the Second Sense, I’ll quote straight from Lintel”s Afterword —

I was paging through an encyclopedia of philosophy when I came across the word “sublime,” which is defined as “the presence of transcendent vastness or greatness” While in one aspect, it is apprehended and grasped as a whole, it is felt as transcending our normal standards of measurement… it involves a certain baffling of our faculty with feeling of limitation akin to awe and veneration; as well as a stimulation of our abilities and elevation of the self in sympathy with its object. The word sublime comes from “sub”(under) plus “limen” (which, like “limit”, is a word derived originally from… “”lintel.””) Though we rarely recognize the place, underneath the lintel is where we stand every day, every moment, of our life. Underneath the lintel there is nothing but a precipice, and before us —– the yawning, staggering, bewildering cosmos. We’re here because we’re here because we’re here because we’re here …

From the Portland Center Stage website

[previous] [next]