Photos by Joan Marcus

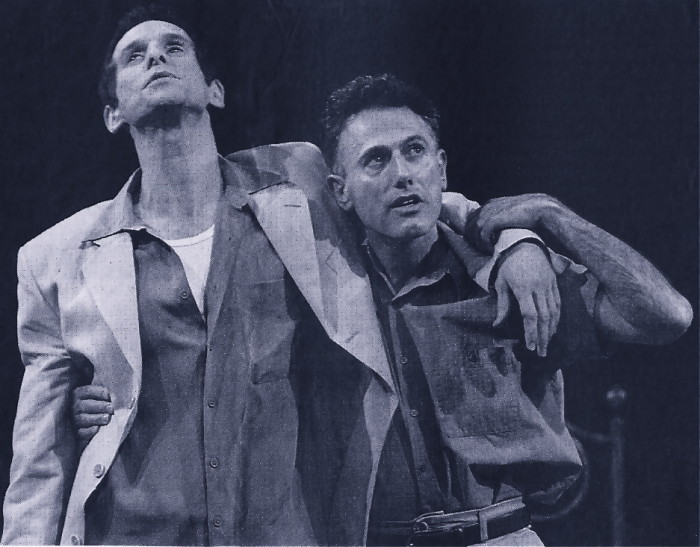

Above, top: T. Ryder Smith and David Greenspan. Below: T. Ryder Smith, Katherine Kerr, Marissa Copeland, David Greenspan.

Excerpts from the reviews

Full reviews are below

“80 minutes of near total delight . . . This is a sex comedy, and the set is a large double bed, which looks comfy and stylish in its splendid isolation. There is a chair off in one downstage corner; when the actors enter upstage, you see the glare of dressing-room fluorescents. The costumes are unassuming contemporary clothes. And the enchanting result of this utter abnegation of illusion is—illusion. Illusion piled on illusion, illusion outrageously toyed with, illusion stretched and twisted and ripped apart and taped back together till the concept of illusion—or of reality—becomes a laugh in itself. And that, I would say, is the theater. Sweeping away everything but the mind of the playwright and the ability of the actors, Greenspan creates a fiction that has the pleasure and pain of life, plus the extravagant possibilities of the imagination. He does it without apparatus, attitude, amplification, willed ugliness, or any of the other tortures that make most of our theater such misery to sit through. It’s just theater, pure and simple. . . . T. Ryder Smith and E. Katharine Kerr, who play Simon and the dual role of Kay/Jayne respectively, demonstrate Greenspan’s sensible, unfussy skill at casting and directing, an outgrowth of his artistic generosity of spirit. Not every playwright-director would be willing to leave the spotlight to actors with such a gift for catching and gripping an audience’s attention. Happy to take stage when the play demands it, Greenspan seems equally content to be an offstage “feed” or part of an upstage chorus while Kerr and Smith, old hands at tricky material like this, dive zestfully into the meaty scenes he’s written for them. “That’s what life is,” one of Kerr’s characters says. “Scenes. One after the other.” Applying equally to stage and audience, the line’s a microcosm of the writing’s lighthearted bravura, always offering you more than its surface suggests. . . . Small, breezy, and near perfect, She Stoops to Comedy is a very big event, tickling up, in its cameo-carved wit, large ideas about love, truth, art, reality, and other matters that concern everyone. You go to the theater, you experience delight instead of agony, you come home exhilarated, and when you wake up the next day, you have an enhanced awareness of life as well as a pleasant memory. I believe this is how the process of theatergoing is meant to work. . . . ” Michael Feingold, Village Voice

“There is energizing music coming out of the fourth-floor Peter Jay Sharp Theater. It’s the sound of David Greenspan’s dialogue, part Gertrude Stein minimalism, part Marx Brothers verbal shtick, as glittering and sharp as a diamond. . . . Greenspan employs direct address, speeches that mutate into inner monologues, and self-referential asides as actors struggle to figure out which draft of the play they’re performing. Elegantly unpredictable and unexpectedly moving . . . “ David Cote, Time Out NY

“An extraordinary new play . . . Not since Charles Ludlam have we had an artist with his depth of feeling, comic flair and ability to juggle multiple tiaras. And like Ludlam he also stars in his own plays. . . . This dazzling tour de force, the theatrical equivalent of a triple axle for ice skaters, also serves its purpose in generating meaning in the performance since the play is about, among things, how theatre gets made. The other things it’s about include, at last count, the fluidity of gender, the slipperiness of identity, the slipperiness of language, the revisions we make in the stories of our life, the eternal conflict among theatre artists between the stage and film, the Gordion knots at the heart of homosexual AND heterosexual couplings, the lies we tell each other to maintain and even reinvigorate our relationships, the often circuitous ways in which we uncover hidden abilities and talents, new love, old love, the sorry state of gay theatre, how AIDS has disappeared from our discourse, and the urgent need we have to love each other and work together to create a better world. . . . In addition to the incomparable Kerr, the playwright gives two of the cast acting moments that theatre folk salivate for. One is for himself at the end of play. Offstage, unseen, he plays a scene with Alison, now home from her trip into the Maine woods. Harry is gone, and now back in New York, Alexandra has reemerged. She is dressing, and merely with his voice Greenspan creates the illusion of gender illusion, for when he emerges he is merely himself, nothing more, nothing less. And of course, this is exactly what Alexandra has learned to be during the course of the play. The second is for Smith, to whom Greenspan gives a stunning monologue from the point of view of the alcoholic, aging, HIV-positive gay actor. How many clichés is that? Which is the point, as Simon rages against all of the structures, literary and societal, that keep gay men isolated, addicted, and afraid. This moment, shocking in its rabid intensity amidst all of the frivolity, reminds us that underneath the mirth there is a well of loneliness in all of us that no amount of laughter can ever fill. It’s the voice of “silent” Simon and T. Ryder Smith that seeps into my blood and haunts me as I write this.” Tim Cusack, nytheatre.com

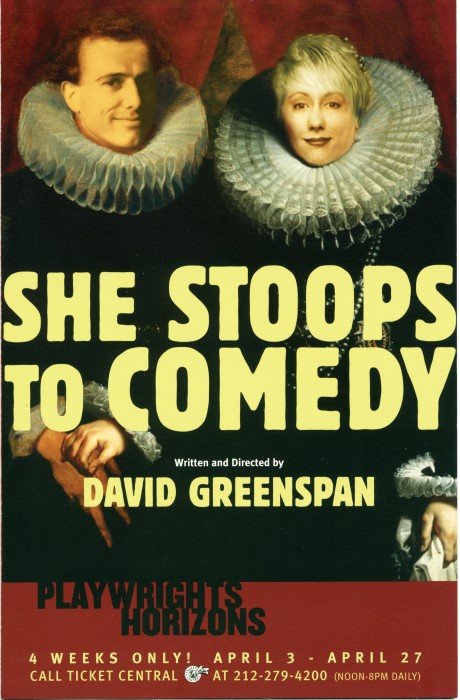

Publicity

Full reviews

Village Voice, Michael Feingold – Gender is the Night. The dark and ugly tunnel that the theater’s been crawling through since modernism died still encloses us, but the bright lights that signal its end are distinctly starting to appear. The brightest such signal to date is David Greenspan’s She Stoops to Comedy, 80 minutes of near total delight, which inaugurates Playwrights Horizons’ new upstairs space, the Peter Jay Sharp Theater. With its gleaming new hardwood floor, the space feels airy and comfortable, partly because the bare simplicity of Greenspan’s aesthetic opens it to full view. This is a sex comedy, and the set is a large double bed, which looks comfy and stylish in its splendid isolation. There is a chair off in one downstage corner; when the actors enter upstage, you see the glare of dressing-room fluorescents. The costumes are unassuming contemporary clothes. And the enchanting result of this utter abnegation of illusion is—illusion. Illusion piled on illusion, illusion outrageously toyed with, illusion stretched and twisted and ripped apart and taped back together till the concept of illusion—or of reality—becomes a laugh in itself. And that, I would say, is the theater. Sweeping away everything but the mind of the playwright and the ability of the actors, Greenspan creates a fiction that has the pleasure and pain of life, plus the extravagant possibilities of the imagination. He does it without apparatus, attitude, amplification, willed ugliness, or any of the other tortures that make most of our theater such misery to sit through. It’s just theater, pure and simple. What a relief. The visible simplicity of She Stoops to Comedy is only a way of clearing space for the emotional complexity of the illusion Greenspan invites you to create. Alexandra, a lesbian thespian famous for playing tragic roles in “concept” productions (you remember her Phaedra in a space suit), is having a bumpy time with her lover Alison, a musical-comedy gal about to try something new (“How often can you be a cock-eyed optimist in Pittsburgh?”). A young indie film director is trying his hand at As You Like It up in Maine, and Alison has been cast as Rosalind. The production’s Orlando has just been lost to Hollywood; in a reckless, lovelorn moment, Alexandra disguises herself as a man (“Harry Samson,” if you please), auditions for the role, and gets it. Among the extra complications she finds in Maine are another lesbian couple gone splitsville, a troubled hetero relationship between the director and his assistant, and Simon Languish, the melancholy gay actor to whose Brick Alexandra once played Maggie. The elegantly conveyed chaos that results is too delicious for me to spoil by describing either what happens or the droll way Greenspan makes it unfold out of itself, labeling all the component parts as they appear; the script is its own running commentary, replete with alternate drafts. (He even identifies the old European play it’s modeled on.) I’ll give two hints of joys to come: The second lesbian couple, lighting designer Kay Fein and actress Jayne Summerhouse, are played by the same actress. (“I hope we don’t have a scene,” Kay says, on learning of Jayne’s presence. “That would be impossible.”) And Simon, having gotten drunk at a post-rehearsal dinner, delivers an inebriate monologue, while Alison and “Harry” help him stagger home, that sums up, hilariously, not only his own life but all the constraints that post-Stonewall gay subculture and its theatrical stereotypes put on male homosexual life. (“I think we’ve been over this ground before,” says Alison, as they pick their tentative way through the Maine woods.) T. Ryder Smith and E. Katharine Kerr, who play Simon and the dual role of Kay/Jayne respectively, demonstrate Greenspan’s sensible, unfussy skill at casting and directing, an outgrowth of his artistic generosity of spirit. Not every playwright-director would be willing to leave the spotlight to actors with such a gift for catching and gripping an audience’s attention. Happy to take stage when the play demands it, Greenspan seems equally content to be an offstage “feed” or part of an upstage chorus while Kerr and Smith, old hands at tricky material like this, dive zestfully into the meaty scenes he’s written for them. “That’s what life is,” one of Kerr’s characters says. “Scenes. One after the other.” Applying equally to stage and audience, the line’s a microcosm of the writing’s lighthearted bravura, always offering you more than its surface suggests. While hardly touching the text of As You Like It (of which it quotes a grand total of two and a half lines), She Stoops is full of puckish thematic and structural parallels: not an update or rewrite of Shakespeare’s comedy but a contemporary work fit to stand next to it. Alison and Alex, its Rosalind and Orlando, are flanked on one side by Kay and Jayne, a no-nonsense Silvius and a less captious Phebe, and on the other by the heterosexual couple of Hal and his assistant Eve, a Touchstone-Audrey coupling in which the dynamics are subtler, and the interaction a good deal knottier, than in Shakespeare’s farce of the court jester and his shepherd lass. Greenspan lets Philip Tabor and Mia Barron play these scenes in a gentle, pale-colored style that forges a disconcerting link between our laid-back film world and the serenity of pastoral poetry. Between the gentle and the brawling couples, in the slow steps back to love of Alison and Alex (a reverse mirror-image of Rosalind wooing Orlando), Marissa Copeland, graceful and heartfelt, makes a charmingly probable match for Greenspan’s charmingly improbable female. I’m nervous about making any evening in the theater sound perfect; high expectations are so easily let down. In Greenspan’s place, I might snip one or two lines, in the few places where he pushes a scene slightly beyond its natural span. I might tone down a few points where the one performer whom the director can’t see goes slightly over the mark. But that’s all. Small, breezy, and near perfect, She Stoops to Comedy is a very big event, tickling up, in its cameo-carved wit, large ideas about love, truth, art, reality, and other matters that concern everyone. You go to the theater, you experience delight instead of agony, you come home exhilarated, and when you wake up the next day, you have an enhanced awareness of life as well as a pleasant memory. I believe this is how the process of theatergoing is meant to work. And I believe that David Greenspan is not the only artist in New York who can make it do so. Why the others don’t is the part I haven’t figured out yet. 4-03

New York Times, Ben Brantley – When a Drama Workshop Goes Berserk, Genders Bend. Experiencing ”She Stoops to Comedy,” the new play written by and starring David Greenspan, is like listening to opera singers practicing their scales after a few drinks. Their voices rove all over the place, not always prettily, but you have to admire the flexibility of their instruments. Anyway, they seem to be having such a good time, who’s going to begrudge them their fun, even if it’s not always possible to share in it? Mr. Greenspan, a cult figure among downtown theater devotees, has created a rambling, self-revising exercise of a play that presents life as a drama workshop. In ”Stoops,” which opened last night at Playwrights Horizons, all the world’s an acting class in which the players’ identities and actions keep shifting according to the whims of a constantly changing script. ”Comedy,” directed by (yes) Mr. Greenspan, centers on a vain actress, Alexandra Page (Mr. Greenspan), who decides to win back her estranged lover, Alison Rose (Marissa Copeland), by dressing up as a man to appear in a provincial production of ”As You Like It” in which Alison is to play Rosalind. Actually, the shape-shifting plot of ”Comedy” takes its cues more from ”The Guardsman,” Molnar’s sexual farce of assumed identity, than from Shakespeare. In this instance, the layers of role-playing multiply in ways that Molnar never dreamed since the disguised lover of ”Comedy” is (take a breath) a man playing a woman who dresses as a man to pursue a woman playing a man. Staged in the naked rehearsal-roomlike space of the Peter Sharp Theater at the new Playwrights complex, ”Comedy” deliberately evokes the feeling of a work in progress, with no obviously theatrical makeup or costumes. (Playing Alexandra in or out of disguise, Mr. Greenspan always looks like Mr. Greenspan.) Packed with theatrical in-jokes and wordplay, ”Comedy” feels dense and exceedingly thin at the same time. It offers little in the way of fresh insight on role-playing, whether theatrical, sexual or existential. But it does allow its performers both to strut and to send up their own skills in virtuosic solo scenes. So you get to see E. Katherine Kerr (of ”Laughing Wild”) conduct a frantic lovers’ quarrel between the two characters she has been assigned to play, while T. Ryder Smith (”Underneath the Lintel”) brings a fine madness to a drunken catalog of a monologue about plays about homosexuals. There are long stretches of tedium among such star bursts. But fans of Mr. Greenspan’s uniquely ornate stage persona will find ”Comedy” worth attending for its opening scene alone. In it, Alexandra, sequestered in a bathroom, turns every sentence she speaks into a platform for the display of artificial emotions that go from A to Z and somewhere beyond. 4-15-03

Time Out NY, David Cote – Playwrights Horizons’ chic, remodeled main stage started off in March on a bad note with the somnolent My Life with Albertine, but there is energizing music coming out of the fourth-floor Peter Jay Sharp Theater. It’s the sound of David Greenspan’s dialogue, part Gertrude Stein minimalism, part Marx Brothers verbal shtick, as glittering and sharp as a diamond. The playwright-actor hasn’t premiered a show in nine long years. Now he’s making a delightful comeback with She Stoops to Comedy, a brain-tickling 80-minute field trip into the absurd wilds of sex and gender.

A giddy intertextual square dance with As You Like It, She Stoops to Conquer and Ferenc Molnar’s The Guardsman, She Stoops shares those other farces’ concern with fidelity and the illusory nature of gender. Greenspan, never changing from tan khakis and a green button-down, plays Alexandra Page, a lesbian actress who dons male drag to infiltrate an out-of-town production of As You Like It in order to spy on her lover, Alison Rose (coltish ingenue Marissa Copeland). Naturally, Alison (playing Rosalind, a woman playing a man who impersonates a woman) finds herself strangely attracted to Alexandra’s Orlando (a woman playing a man). Filling out the backstage comedy is a bitter gay actor (T. Ryder Smith), a clueless director (Philip Tabor) and his pert assistant (Mia Barron). E. Katherine Kerr shoulders multiple roles, eventually having a two-person scene all to herself.

Greenspan employs direct address, speeches that mutate into inner monologues, and self-referential asides as actors struggle to figure out which draft of the play they’re performing. Elegantly unpredictable and unexpectedly moving, She Stoops to Comedy proves that Greenspan, along with Wallace Shawn, is a tough-minded playwright long due a retrospective of his own (hint, hint Signature Theatre Company!). 4-17-03

CurtainUp, Elyse Sommer – Meet Alexandra Page, a tempestuous lesbian actress who has good cause to be depressed. Her career is going nowhere and neither is her relationship with her lover. As played by David Greenspan, who also wrote and directed Alexandra’s story, expect her despair to be a hilarious, high-voltage rant chockfull of observations about the theater in general; and, with a title like She Stoops to Comedy, don’t be surprised if the play is a modern tale with old theatrical links. While I’m usually leery of plays starring and directed by their author, Greenspan makes a brilliant case for the triple threat approach. He has created a terrific role for himself, without short-changing his collaborators. The play overall is challenging — avant-garde and yet accessible enough for anyone willing to stretch themselves to meet Greenspan’s deconstructivist’s imagination half way to have a wonderful time. His direction is inventive and his acting sets the standard for all around performance excellence. Playwrights Horizon couldn’t have picked a better play to launch its new smaller second stage which is dedicated to nourishing fresh talent and enabling experienced playwrights like Greenspan to push their creative envelopes. Stylistically this world premiere is a sendup of Elizabethan theatrical conventions — disguise, soliloquies, audience asides — and what better way to do so than to wrap the play within one of Shakespeare’s best known disguise comedies, As You Like It.

It’s hard to harness the eighty minute happenings to a conventional plot summary, but here’s how the play we see evolves into the play within it: Allison Rose (Marissa Copeland), Alexandra’s girlfriend is about to head for Maine where’s she’s been cast as Rosalind in a production of As You Like It. Shades of Molnar’s plot device in The Guardsman and Mozart’s in cosi Fan Tutte (The Guardsman, in case you forgot, has a jealous actor decides to test his wife’s fidelity by wooing her in disguise), Alexa, hoping to salvage his rocky relationship, decides to try out for the part of Orlando. The staging is bare bones, with the only scenic prop a brass bed near the front of the Peter Jay Sharp Theater’s deep stage (the stage is as deep and wide as the seating area). For all the simplicity of the production, it’s all , as one of the play’s characters observes, “very complicated.” since nothing follows typical theatrical custom so that at times the script is revised on the spot, as when Greenspain steps out of character and remarks “that’s a typo.” Complicated as it may be, you do catch on. The actors enter from upstage and walk forward, as for a reading, then disperse and it’s quickly apparent that the side section where Greenspan positions himself for his opening monologue is the bathroom where he is (supposedly invisible to the audience) putting on his Orlando disguise as a man, properly flat chested and with hair on his arms that he quips “once belonged to Laurence Olivier.” Once you buy into this set-up it’s not hard to figure out when E. Katherine Kerr is Kay Fein and when she’s Jayne Summerhouse (a sly nod to a Jane Bowles character of that name). Alexa’s disguise is, of course, Greenspan looking exactly like himself . That “disguise” established, it’s on to Maine and the audition with director Hal Stewart (Philip Tabor supplying the right touch of Hollywood guy trying to be arty guy) and his assistant and girlfriend Eve Addaman (Mia Barron as a rather minor chracter whose name is something of a running joke). To add to the fun of Greenspan and Copeland’s newly blossoming romance courtesy of their As You Like It disguises, the various characters often shift mood and identity in mid-scene and deliver monologues. One quite touching monologue comes from another wittily named character, Simon Languish (T. Ryder Smith). True to his fictional name Smith starts out as a background figure but explodes into a tour-de-force biographical riff in which he sums himself up as a walking cliche. If this were a musical, it would be a ballad titled ” Who Needs Another Actor?” Best of all is E. Katherine Kerr’s spot-on soliloquy in which she switches from her stage lighting designer to her archeologoist persona with drop-dead timing. At one point she hilariously scolds herself for getting her roles mixed up. Ultimately She Stoops to Comedy is an extended intellectual joke disguised as a comedy — but that joke is genuinely funny and subversively thought-provoking. With a closing date set for the end of the month, catch it while you can. 4-12-03

Variety, Charles Isherwood – David Greenspan puts the play back in playwriting in this clever lark of a comedy about life in the theater, or life and the theater. The author, who also stars and directs, treats the stage as his sandbox. He’ll set up the identity of a character, then erase it and start all over again — now she’s an archaeologist, now she’s a lighting designer. It’s 1950, no, 1970, no, yesterday. A long aside to the audience dissects the confusions of just such digressions.

Greenspan is clearly intoxicated by the freedom that theater allows, and it’s an infectious feeling. Some of the many plates he sets spinning wobble a bit — particularly when he begins to downplay the high spirits and shift gears into a more ruminative examination of sex, gender and relationships. But the play is consistently surprising, full of smart wordplay and inventive bits of business that poke fun at the artifices of the art form while reveling in them. The self-apparent deceptions begin with Greenspan casting himself as Alexandra Page, a self-dramatizing actress who opens the play with a long aria that sets the preposterous tone with its great gusts of verbiage delivered at fever pitch. Greenspan recites this anguished description of Alexandra’s recent breakup with a girlfriend in a hilariously florid and occasionally incomprehensible whine, clinging dramatically to the wall. To win her lover back, Alexandra has decided to descend on the small town in Maine where Alison Rose (Marissa Copeland) is appearing as Rosalind (get it?) in “As You Like It” (naturally). Her hope is to get herself cast as Orlando. Yes, this means Greenspan is a man playing a woman playing a man. But downtown theater watchers familiar with his rococo acting style will know that this is really not much of a stretch. Alison herself is happy to have a chance to stretch her acting muscles. She’s a specialist in regional musical comedy who’s getting a bit exhausted. (“How many times can you play a cockeyed optimist in Pittsburgh?” Alexandra cracks.) And Alexandra is tired of playing “angry, depressed women” in pretentious modern versions of classics like “Biff at Colonus.” But her new role brings its own disquieting revelations, too: Cozying up to Alison in her guise as a man, she is privy to her lover’s cool assessments of her own flaws. The farcical possibilities inherent in the setup are amusingly explored (Alexandra flees to the men’s room to answer a cell phone call from Alison), but Greenspan isn’t exclusively interested in presenting a traditional comedy, however untraditionally it is conceived. He spends as much time sending up some of the practicalities and conventions of contemporary theater. Double-casting, for instance, comes in for extended ribbing, as E. Katherine Kerr plays both Kay Fein, the no-nonsense lighting designer on the production (and erstwhile archaeologist) and her ex-lover, glamorous actress Jayne Summerhouse. “I’d love to see you?” Summerhouse says, on the phone with Kay. “Would that be possible?” Why not? This is the theater, and who wants realism? The virtuosic dual monologue in which Kerr plays a long argument between these ex-lovers, flipping instantly from Kay’s bitter pragmatism to Jayne’s girlish evasions, is possibly the comic highlight of the play. But amid the cockeyed highjinx there are also some more earnest digressions that can be deflating. The play’s gay character, an actor named Simon Lanquish (T. Ryder Smith), takes aim at the audience in a long, bitter rant that sarcastically accuses us of turning away from the painful subjects of gay men’s sufferings now that they’re no longer the flavor of the month on the stage. The point is well taken, but it’s being made in the wrong play. And the scene in which director Hal Stewart (Philip Tabor) and his assistant and girlfriend Eve Addaman (Mia Barron) describe their fluctuating emotions and thought processes as they prepare for bed doesn’t have much of a payoff. Then again, the play as a whole doesn’t either. But that’s part of its charm: In its conscious airiness and aimlessness, it celebrates the transitory, ever-malleable nature of the theatrical form, lovingly honoring the freedom from structure that the stage can afford a writer. Greenspan would rather build a pile of pretty sandcastles than a real house. That’s an artist’s prerogative. So what if a few are a bit lopsided? 4-22-03

Theatremania.com, Philip Hopkins – She Stoops to Comedy is a delightful new farce written and directed by David Greenspan, in which he also stars. The play actually has little to do with She Stoops to Conquer, the delightful old farce by Oliver Goldsmith, which first appeared in London in 1773. It has stronger parallels to its acknowledged forerunner: The Guardsman, by Ferenc Molnar, Hungary’s foremost playwright and an influence on such major figures as Pirandello. But Greenspan’s triple-threat approach to playmaking also recalls the work of Charles Ludlam, whose Irma Vep is referenced prominently here. The play is marked by fast-paced, articulate, poetic, and rhythmic text, delivered by a cast in perfect tune with the style. Repetition figures strongly in the writing, as does gentle rhyme, which tickles the ear at various moments. But the essence of this work is Greenspan’s love of gender-farce in all its forms, mixed with a palpable (and increasingly rare) respect and affection for the audience, which the author treats as a collaborator. Greenspan’s elated theatrical gender games were given a mixed reception when offered a decade ago at The Public Theater under Joseph Papp and George C. Wolfe. Now, they make for a cocktail frothy enough to allow “the permissiveness of theatrical artifice” — as a line in Comedy goes — to take over entirely. The play succeeds most when it is appreciating life as theater and pointing out that the roles of life don’t always fit the individuals who play them. Indeed, the piece is sometimes too in love with artifice to slow down and fully engage reality; when it does so, its devices stretch and strain. Yet the play as a whole is riveting for its insistence on the profundity, the reality of the artificial. At issue here is a regional theater staging of As You Like It in Maine. Greenspan plays Alexandra Page, a lesbian actress who has decided to impersonate a man in order to be cast as Orlando in the production. He plays the role with no makeup and costumed as a man called Harry Samson. Also starring in As You Like It is Page’s ex-lover Alison Rose, played by Marissa Copeland. Their meeting is a magic moment in which — as the play itself notes in quoting a review of its own source, The Guardsman — a twinkle is present in Copeland’s eye but “you’re never quite sure what’s behind that twinkle.” The play’s director Hal Stewart, played by Philip Tabor, is a film guy who’s never done theater before and who gets stuck on the first query about the text that is raised by an actor. Hal’s assistant and girlfriend Eve Addaman, played by Mia Barron, struggles for a chance to apply her own directorial talent to the proceedings and to make her relationship with Hal workable. (Theirs is the token heterosexual romance here but its unfolding is the most tender and involving of them all.) Alexandra’s friend Kay Fein, a lighting designer, advises her on her problems and contends with her own relationship with Jayne Summerhouse. As both Kay and Jayne, E. Katherine Kerr is a pleasure to watch; she pulls off with remarkable skill a scene in which the two characters argue, though Greenspan’s writing and direction might have served her better here. The most bravura acting in She Stoops to Comedy is done by Greenspan, whose slinky movements and high, silky voice weave a spell that remains unbroken throughout. There is some chicanery with cell phones when Alison thinks she’s calling Alexandra and Greenspan as Samson has to jump up and juggle things a bit, but it reminds us of the fondness and care that this writer-director-actor has lavished on the conventions of gender farces, from the works of the Bard to Some Like It Hot. One wishes that there were more gut-level revelations in the piece; we learn of only one character’s dissatisfaction in a genuinely arresting sequence featuring T. Ryder Smith as Simon Lanquish, the desperate, gay actor whose loneliness is expressed in a monologue that’s well delivered but tonally out of place with the rest of the material. When Greenspan tries to put too much reality onstage, he loses his grip on his devices — and when he is indulging in his devices, reality is at arm’s length in a way that pleases but does not always involve us. Nonetheless, kudos to Playwrights Horizons for giving Greenspan another platform for his creations. At a time when commercially motivated projects lead to decisions by committee posing as theater, individual visions based on a true love of the stage are refreshing. Any disciple of theatrical illusion as loving as is David Greenspan should be treasured. 4-14-03

Offoffoff.com, Caraid O’Brien – Double drag. David Greenspan’s latest work, “She Stoops to Comedy,” is poised to sweep the Obies this year and I am not sure why. (Everyone else liked it, could I have seen it on a bad night? Do shows uptown have bad nights?) In his play about how an author writes a play (I need a new character, ‘k. fine. I’ll call her Kay Fein), Greenspan’s roles as director, author, actor and character are constantly being alluded to throughout the performance. When not in the scene, he sits on the sidelines and watches the action. The characters reference themselves in frequent interior monologues (the audience thinks the other characters can hear me speaking now!) which is a clever if ubiquitous device used liberally throughout this piece. It was almost exciting to see the downtown aesthetic of the late eighties/early nineties (when Greenspan first made his mark) dusted off for an uptown audience, but a certain glam and glamour was gone. Greenspan plays an actress dressing in drag and so actually looks just like himself in street clothes (the play’s Big Idea!). Heavily schooled in the trademark style of the Theater of the Ridiculous, Greenspan strips down gay stereotypes into a bland, gap aesthetic for this show. While Charles Busch made his drag queen into Linda Lavin for Broadway’s “Allergist’s Wife,” Greenspan takes the repackaging a step further. In an attempt to scrub away queeny clichés (while still playing a queen), Greenspan decamps the camp — not just taking out the drag queens but playing it straight — creating a new hyperminimalist, supposedly intellectual camp style that’s just not as fun. Greenspan alludes to Charles Ludlam’s most famous work, “Irma Vep,” by attributing the generic line “I beg your pardon” to the legendary scribe, but his script makes you think more of Ludlam’s “How to Write a Play.” The play’s play is about Alexandra Page, a lesbian actress whose lover Alison gets a role in a Maine production of “As You Like It.” The promising young male lead — a French-Canadian with a speech impediment, drops out and Alexandra decides that she in disguise will try out for the male lead. Greenspan spoofs independent film directors with the Hal Hartleyesque character Hal Stewart who directs the Maine production with a Shakespearean cast of four and is well played by Philip Tabor. The script is very fey and endlessly self-referential — joking about postmodern theater and What is it? and Are we it? The costumes looked like the actors’ own clothes. The set was curtainless and bare except for a bed. The seeming economy of the production values didn’t jibe with the Playwrights Horizon’s shiny new Peter Jay Sharp Theater with its uncomfortable college lecture hall style seats. (Has the rowdy, raucous, seamy downtown theater been transformed into a Starbucks-Ikea like existence? Is this success?) The actors play it straight and under par with the possible exception of Greenspan, whose lesbian actress was more of a photocopied version of the homosexual male stereotypes — as actor T. Ryder Smith bemoans in his very long, almost exhilarating monologue about gay clichés in the theater. What was exciting about this moment is that it seemed a minor character who had previously delivered only a handful of lines, was about to hijack the play — taking center stage for about ten minutes, saying repetitively: Who needs another play about a gay man who _______ ? (Fill in the blanks: is a hairdresser, has AIDS, is lonely, etc.) But then he quickly recesses into the background once again. This sweet-spirited play (I wished I liked it, I wanted to like it) would have been fun in a dusty storefront ten years ago with a little more moxie, but the humor was too in-crowd droll to be funny here, especially when stripped of the high-energy supertheatricality of the downtown theatrical milieu of the nineties, palpably missing from this production. 4-24-03

Newsday, Gordon Cox – In This Shellgame, Ambivalence Is No Drag. In “She Stoops to Comedy,” the actor, writer and director David Greenspan does indeed play a woman – and a flamboyantly theatrical one at that – but don’t expect to see him decked out in drag. Greenspan embodies the flouncing actress Alexandra Page wearing unremarkable (and unmistakably masculine) street clothes: a green short-sleeved shirt tucked into khaki pants.

This can be partially explained by the fact that Alexandra spends most of the play in her own version of drag, posing as a man so that she can win back her ex- lover, Alison (Marissa Copeland), by starring opposite her in a regional production of Shakespeare’s “As You Like It.” But really, everything is transparent in this mischievous new comedy, from the mimed props to the script’s openly acknowledged narrative devices to the in- plain-view offstage spaces of Playwrights Horizon’s Sharp Theater, where the play opened last night.

In fact, the entirety of this intellectual shellgame of a show is something of a postmodernist joke, comically shuffling questions of performance, gender, identity and writing. That it all feels centerless and ultimately hollow is surely part of the point, and there’s still something slyly affecting (and, quite often, very funny) about the production’s chronic ambivalence.

Scenes abruptly abort and restart; character traits change in mid- conversation; storytelling conventions bump jarringly against each other. We’re watching Greenspan the writer rethink and revise his script, while Greenspan the director heightens our awareness of the artifices of acting by stripping away most other theatrical adornments, leaving just six actors and a bed on a bare stage.

He’s especially keen on the artificiality of gender markers, deflating them, as an actor, by playing Alexandra with an initial squealing swishiness that slowly simmers down into a quieter fluidity. He approaches, finally, the unostentatious performance style of the majority of the cast (especially the deftly understated Copeland and the subdued, forlorn T. Ryder Smith), a shift that’s an important part of the play’s investigation of how much of acting is essence, and vice versa.

The most sustained theatricality, meanwhile, comes from the double-cast E. Katherine Kerr, who plays both her roles with knowing wit. But Greenspan blurs even the line that divides her clearly delineated character work, so that, late in the show, the scene Kerr plays opposite herself begins to seem like an argument taking place between two irreconcilable sides of the same person.

The play’s more serious second half takes on the failure of expression in ways that don’t feel entirely integral to the stage- world Greenspan has created. But then nothing quite fits as expected in “She Stoops to Comedy,” building, as it does, to a transformative payoff that isn’t a payoff at all in the end. And, somehow, there’s something satisfying in that disappointment. 4.14.03

nytheatre.com, Tim Cusack – Good theatre makes me happy. Great theatre makes me sweat. I have a theory about this: Theatre that meets or surpasses standards I store in my cerebral cortex amuses me, validates my opinions, assures me that I haven’t wasted time better spent on That 70s Show reruns. But every once in awhile an event comes along that, while fully engaging my higher cognitive realms, simultaneously bypasses them and starts firing up my amygdala. This theatre I feel in every ganglia, gland and capillary of my body. That’s the kind of theatre David Greenspan’s extraordinary new play She Stoops to Comedy is. Stop reading this review, go to the sidebar at left and order a ticket, no make that 10 tickets, right now. Go on. This show deserves to sell out its entire run, be extended into perpetuity, and provide Greenspan with a nice nest egg so that he can go on making his idiosyncratic theatre, which, if you ask me, this town desperately needs. Not since Charles Ludlam have we had an artist with his depth of feeling, comic flair and ability to juggle multiple tiaras. And like Ludlam he also stars in his own plays.

This dazzling tour de force, the theatrical equivalent of a triple axle for ice skaters, also serves its purpose in generating meaning in the performance since the play is about, among things, how theatre gets made. The other things it’s about include, at last count, the fluidity of gender, the slipperiness of identity, the slipperiness of language, the revisions we make in the stories of our life, the eternal conflict among theatre artists between the stage and film, the Gordion knots at the heart of homosexual AND heterosexual couplings, the lies we tell each other to maintain and even reinvigorate our relationships, the often circuitous ways in which we uncover hidden abilities and talents, new love, old love, the sorry state of gay theatre, how AIDS has disappeared from our discourse, and the urgent need we have to love each other and work together to create a better world. There are probably about 20 other things it’s also about that I’ve absorbed on the cellular level but haven’t even begun to process in the ol’ meat computer. Richard Foreman has famously said that Gertrude Stein is his mother and Bertolt Brecht is his father (artistically, at least). The same can be said of Greenspan. But where Foreman is the bitterly brooding son of this family, given to fits of hysteria, Greenspan is the gregarious people-pleaser, given to outbursts of vintage movie dialogue. Like Foreman’s his language circles around itself, but the effect is more like a pleasant stroll around the neighborhood where one keeps noticing previously hidden details in buildings you’ve seen dozens of times rather than a manic descent through rings of hell. And unlike Foreman, Greenspan isn’t afraid of constructing a good, rip-roaring plot—the details of which I’ll attempt to summarize here. Not an easy task given its complexity. Although that’s yet another idea in the play: the futility of trying to reconstruct memory, of ever knowing “what really happened.” Alexandra Page (Greenspan), an actress of some renown, has reached an impasse in her career and her life. Her younger girlfriend, Alison Rose (Marissa Copeland), has left New York for the summer to appear as Rosalind (note the anagram) in a Maine production of As You Like It. Alison’s Celia in the production is the theatre star Jayne Summerhouse (E. Katherine Kerr). Alex knows that Jayne has always had a thing for Alison and, aware of the peculiar erotic charge summer stock has for actors, is understandably anxious about losing her girlfriend to a more successful rival. Partly to keep an eye on her partner, partly in an attempt to breathe new life into her career, she decides to audition for the role of Orlando. At the start of the play Alexandra’s friend Kay Fein (also played by Kerr) is paying her a visit while she prepares to meet with the director. To complicate the plot even further, Kay, who is sometimes an archeologist, sometimes a lighting designer, is also Jayne’s ex-lover. As their conversation unspools, not only does Kay’s profession keep shifting but so does the year and Alexandra’s career history. From the start, Greenspan’s text keeps pushing us to the epistemological edge; everything we think we know about these people is going to be multiplied, then undermined. Far from an exercise in futility, this philosophical workout feels liberating; all of these possible pasts imply potential futures, any one of which can be chosen. Alexandra emerges from the bathroom in “drag,” and of course, it’s merely Greenspan in an ordinary shirt and pair of khakis. “Her” drag pseudonym is Harry, a bad pun that Greenspan somehow magically manages to get to pay off every time it’s (s[he’s]) introduced. At the audition Alison and Harry meet and chemistry immediately starts bubbling between them. The director, Hal Stewart (Philip Tabor), an independent film director dabbling in theatre, stays true to his celluloid roots and casts Harry based solely on the sparks given off at this first meeting. Herein lies another joke, Harry’s (Alexandra’s [Greenspan’s]) theatrical artifice outsmarts and trumps Hal’s movie-director obsession with “realness.” Now, as the structure of Shakespeare’s pastoral comedies demands, the play shifts from the city to Arden or in this case, Maine, and the romantic/erotic entanglements begin to ensnare all of the characters. In addition to the characters already mentioned there is Eve Addaman (Mia Barron), Hal’s girlfriend and stage manager who, as it turns out, is the real brains of the operation, and Simon Lanquish (T. Ryder Smith), introduced by Jayne as silent Simon. Soon Simon is chasing Alexandra, thinking she’s a man; Jayne is chasing Alison; Alison is flirting openly with Alex, even though she’s not really attracted to “men”; and Alex is shyly courting her own girlfriend in the guise of a man. When Kay Fein drops in on our merry band, we know it’s only a matter of time before Kerr will have to play a seduction scene with herself. And she does, stopping the show cold with her bravura solo depiction of the confrontation and reconciliation between Kay and Jayne. But this moment is just the center diamond in a jewel that sparkles with multiple-hued facets. The entire cast performs at the highest level of comic intensity, emotional honesty, and ensemble esprit de corps. But even among equals some are more equal than others. In addition to the incomparable Kerr, the playwright gives two of the cast acting moments that theatre folk salivate for. One is for himself at the end of play. Offstage, unseen, he plays a scene with Alison, now home from her trip into the Maine woods. Harry is gone, and now back in New York, Alexandra has reemerged. She is dressing, and merely with his voice Greenspan creates the illusion of gender illusion, for when he emerges he is merely himself, nothing more, nothing less. And of course, this is exactly what Alexandra has learned to be during the course of the play. The second is for Smith, to whom Greenspan gives a stunning monologue from the point of view of the alcoholic, aging, HIV-positive gay actor. How many clichés is that? Which is the point, as Simon rages against all of the structures, literary and societal, that keep gay men isolated, addicted, and afraid. This moment, shocking in its rabid intensity amidst all of the frivolity, reminds us that underneath the mirth there is a well of loneliness in all of us that no amount of laughter can ever fill. It’s the voice of “silent” Simon and T. Ryder Smith that seeps into my blood and haunts me as I write this. 4-12-03

[previous] [next]