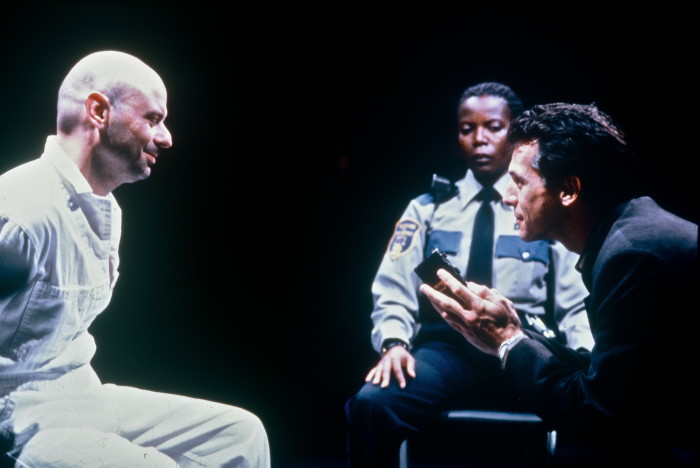

Above, top to bottom: Lee Sellars, Cherene Snow, T. Ryder Smith; Lee Sellars and Paul Sparks; Paul Sparks: Lee Sellars and Paul Sparks; T. Ryder Smith, Lee Sellars, Cherene Snow; Paul Sparks on set

Excerpts from reviews

“Loosely inspired by the playwright’s correspondence with a Texas prisoner, ‘Coyote’ examines the relationship between two diametrically-opposed death-row inmates – John, the educated, intelligent , liberal editor of the prison newspaper, and Bobby, the young white racist mass-murderer in the next cell. . . .Despite exemplary staging and performances, Graham’s [play] is overly simplistic. . . “ J. Wynn Rousuck, The Baltimore Sun

“This play acts as if it’s tackling a tough question . . . but in fact takes shortcuts around all moral difficulties. It is, however, cracklingly well-directed by Lou Jacob and acted through the roof by Sparks and Sellars . . . “ Jane Horwitz, The Washington Post

“A grim, pulsing play . . . A compelling, subtly argumentative script, a great concept, and strong actors . . . “ Jack Shay, Sidewalk.com

Full reviews

Baltimore Sun, J. Wynn Rousuck – A provocative summer of discontent. Forget musicals, Shepherdstown festival puts on four new plays that face tough issues head on. While other summer theaters dish up menus of tried-and-true musicals and murder mysteries, the nine-year-old Contemporary American Theater Festival is taking on abortion, the death penalty, child abuse and female impersonation. And though none of this year’s four plays — whose settings span three centuries and as many continents — is a masterpiece, each dares to take theatergoers to a place they may never have been. Producing “provocative material that’s … relevant and immediate to today’s society” is the festival’s mission, according to founder and producing director Ed Herendeen, who, in less than a decade, has turned his vision into the area’s foremost professional summer festival dedicated exclusively to exploring new work. What Herendeen has created is a smaller version of the prestigious Humana Festival at the Actors Theatre of Louisville. Both festivals stage full productions of new plays. But unlike Louisville, which only produces premieres, Shepherdstown also produces second, and even third, stagings, as is the case with two of this year’s offerings. “A lot of theaters, for some reason, don’t want to do the second production,” says Herendeen, who personally selects all the scripts. “We’re continuing to breathe life into plays that I also think deserve future productions.” Shepherdstown might seem an unlikely place to launch new, tough-minded plays, but the festival’s strong track record has allowed it to extend the season a week longer this year and to add an extra performance each week. Performed in rotating repertory, all of this season’s plays are proficiently produced and display individual merits. Three of the four, however, allow issues to overtake drama — particularly when the playwrights bend over backward to provide a sympathetic depiction of the less sympathetic side of an argument. Still, new plays, by definition, are the future of theater, and developing them is some of the most important work a theater can do. Even if all four plays are not “almost heaven,” the process is, and this West Virginia festival makes it well worth the trip. Loosely inspired by the playwright’s correspondence with a Texas prisoner who edited a prison newspaper called the Death Row Journal, Bruce Graham’s “Coyote on a Fence” examines the relationship between two diametrically opposed death-row inmates — John (Lee Sellars), the educated, intelligent, liberal editor, and Bobby (Paul Sparks), the young white racist mass murderer in the next cell. Directed by Lou Jacob on designer Klara Zieglerova’s grim, runway-shaped prison set, with theatergoers seated on either side, “Coyote” is the festival’s slickest production. Yet despite exemplary staging and performances, Graham’s method of making us care about Bobby is overly simplistic. With his hands dangling at his sides and a goofy grin on his face, Sparks’ Bobby is like a gleeful puppy. One of the playwright’s more telling touches is having this childlike man specialize in doing animal imitations. What seems an amusing, innocent pastime is also eerily fitting for a man whose crime — setting fire to a black church and killing the entire congregation — brands him an animal. John finds everything about his ignorant cellmate reprehensible — until a New York Times reporter doing an article about John researches Bobby’s case for him. The unrepentant racist killer turns out to be a victim of everything from fetal alcohol syndrome to abandonment. Suddenly John is determined to spare Bobby from execution. Although the connection that develops between the prisoners is plausible, John’s eventual fate isn’t. In addition, portraying a heinous criminal as an intellectually stunted, almost cuddly child isn’t half as challenging as it would be if John and Bobby were intellectual equals. In the end, making Bobby a victim is a less sympathetic ploy than a stereotypical one. Wendy MacLeod’s “The Water Children” is also heavily issue-oriented — dramatizing the abortion debate with a look at a pro-choice actress who accepts a job making an anti-abortion commercial. The playwright tries to create a meeting of the minds by depicting the head of a national anti-abortion organization as a man who’s not only intelligent, he’s charming enough to turn the actress’ head. Tony Carlin’s Randall — an apparent reference to former Operation Rescue head Randall Terry — is suave without being oily, a man who appears eminently likable, until you meet some of the demented souls he has taken under his wing. These include two teen-agers — a girl (Michelle Federer) whom Randall’s organization supposedly rescued as a discarded late-term fetus, and a rabid gun nut (Dallas Roberts). The actress, Megan (Susan King), may be swayed by Randall’s charm, and he may even have altered her feelings about abortion, but she should see very large flags when she encounters his teen-age disciples. The play features a few notable theatrical elements. There’s an intriguing cultural shift at the end, when Megan takes a job in Japan and discovers Buddhism’s accepting attitude toward abortion. And, scattered throughout the action are fantasy sequences involving the child Megan aborted when she was a teen-ager. Here again, however, the playwright loads the dice by idealizing the child, just as she idealizes Megan’s mother, and, in the final scene, Megan herself. “Tatjana in Color,” by Julia Jordan, is based on the life of Egon Schiele, an early 20th-century Austrian artist who was convicted of having an improper relationship with a 12-year-old model. Like Paula Vogel’s Pulitzer Prize-winning “How I Learned to Drive,” “Tatjana” looks at the subject of child molestation from the perspective of the child. But once again, the balance is skewed. The play is set in a small Austrian town in 1912, the year Schiele (Michael Tisdale) was convicted of corrupting a minor. As played by adult actress Elizabeth Reaser, this forward 12-year-old girl is temptation incarnate — a demon child who is dangerous to herself and everyone around her. The action essentially consists of Tatjana becoming more and more obsessed and out of control. There are hints that her repressive home and school life may have contributed to her wildness. But because Jordan fails to flesh out Schiele, or most of the other characters (despite Anne Torsiglieri’s poignant portrayal of Schiele’s mistress), the play comes across as kind of an art history horror story. Jeffrey Hatcher’s “Compleat Female Stage Beauty,” set during the Restoration, also concerns a real-life figure — Edward Kynaston, the last great actor to specialize in female roles before actresses were allowed on the English stage. The festival’s most ambitious offering, “Compleat Female Stage Beauty” is a co-commission with Pittsburgh’s City Theatre, where it will be presented in the fall. A large-scale costume drama with numerous settings — backstage, on-stage, a London park, the palace of King Charles II, etc. — it is beyond the budget of most theaters, and Michael J. Dempsey’s set, while serviceable, is relatively basic. Hatcher doesn’t merely tell the semi-fictionalized story of actor Edward Kynaston, whom diarist Samuel Pepys (the play’s narrator), once described as “the most beautiful woman” in the theater, he filters parts of it through a modern sensibility, not unlike that used in the Academy Award- winning movie, “Shakespeare in Love.” (At one point, for example, a Hollywood-sounding Kynaston demands casting approval.) Conveying this sensibility without jarring the audience is tricky, and under Herendeen’s direction, the cast doesn’t always carry it off. Even so, with the exception of T. Ryder Smith, who plays Charles II as a buffoonish caricature, most of the characters seem real. This is especially true of Dallas Roberts’ Kynaston, who, far from being heroic, is portrayed as proud, stubborn and vain, yet succeeds in being affecting when his fortunes turn. Hatcher is the festival’s best-known playwright, and he understands his craft. But partly because of the similarity to “Shakespeare in Love” (which also involved cross-dressing) and partly because of the extensive settings, this is a play that would probably work better on screen. 7.19.99

[previous] [next]