Above: T. Ryder Smith and Rita Pietropinto; Laura Esterman; ensemble; ensemble; T. Ryder Smith and Will Marchetti; Rita Pietropinto, T. Ryder Smith, Laura Esterman, Will Marchetti; Rita Pietropinto and T. Ryder Smith; same; same; ensemble.

Excerpts from the reviews

“A spot-on, wickedly funny satire . . . Imagine a weekend spent in the woods with poets Sylvia Plath, Anne Sexton, Ted Hughes, and Robert Lowell – or, not with them exactly, but with their twisted, blacker-than-life legends. It wouldn’t exactly be fun, but it certainly wouldn’t be boring. . . by the end of the production they’ve wormed their way into your subconscious, screaming passionate, bloody murder . . . Anne and Sylvia are rabidly suicidal, Bob is stuck in a literal and creative state of impotence, while sexy Welsh Ted comes crashing through the poetry world howling about owls, wolves and ‘undermyths’, as Byronic a poet/loverman as they come . . . Even the ghost of Emily Dickinson drops in . . . Blanka Zizka revels in the character’s quirks . . . as well as the play’s sharp explorations of gender and psychological motivation . . . Each actor in the poetic quartet is strong and memorable . . . They feed off each other . . .” Wendy Rosenfield, Philadelphia Weekly

“When the poets insult one another, when Robert . . . twists Ted’s arm until it breaks, when Ted rapes his wife Sylvia amid the spinach and mashed potatoes on the kitchen table, they do it all in free verse. . . the clotted and gnarled diction of modern poetry that brilliantly parodies [Freed’s] various models. . . . As we are first getting to know the characters, the play is great fun: fizzy, disturbing, verbally brilliant, neurotically madcap, delightfully repellent. The comedy sparkles; the poetry . . . astonishes us. Blanka Zizka’s staging is breathtaking. And all the actors have just the right amount of appeal to make us like their loathsome and pathetic characters: Smith gets Ted’s sexy smarminess . . . “ Cary M. Mazer, Philadelphia CITYPAPER

“It takes a discriminating ear to send up this kind of [poetic] material, not to mention a subtle, wicked wit and a command of language . . . Freed respects the difference between satire and burlesque . . . The result is often very funny . . . I laughed a lot . . . but I wanted to feel involved with it as well, and I couldn’t . . . Buoyant direction and first-rate performances . . . “ Clifford A. Ridley, The Philadelphia Inquirer

Offstage

Above: Amy Freed, T. Ryder Smith, Maggie Siff, Blanka Zizka, Joe Guzman, Rita Pietropinto, Laura Esterman, Sally Mercer.

Above: with actor Joe Guzman at “places” call; with Literary Manager Emily Morse; with director Blanka Zizka.

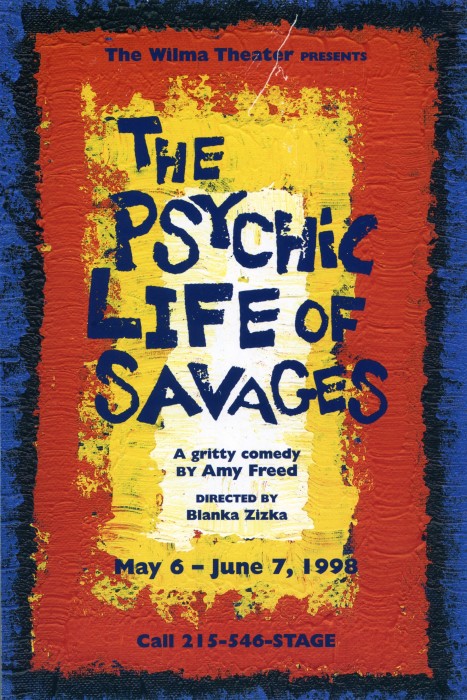

Publicity

Footnote

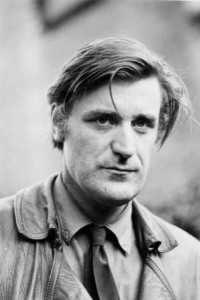

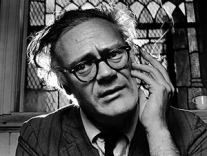

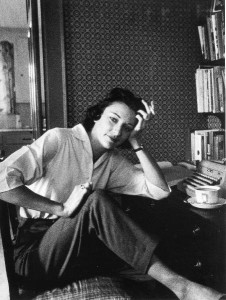

Above, the historical models for the characters. Clockwise from top: Ted Hughes, Sylvia Plath, Anne Sexton, and Robert Lowell.

Full reviews

Philadelphia City Paper, Cary M. Mazer – There are two premises you have to accept to enjoy Amy Freed’s play, The Psychic Life of Savages, now at the Wilma Theater.

One premise is that poets of the 1950s and ’60s – such as the four central characters, Sylvia Fluellen (Rita Pietropinto), Ted Magus (T. Ryder Smith), Anne Bittenhand (Laura Esterman) and Robert Stoner (Will Marchetti) – are acutely psychotic, abusive, egocentric, suicidal, destructive and self-destructive jerks. Given the real poets on whom these characters are loosely – only loosely – based (Sylvia Plath, Ted Hughes, Anne Sexton and Robert Lowell), this premise isn’t all that difficult to accept.

The other premise is that poets talk poetry almost all the time, that images spring to their minds and roll off the tongues spontaneously, and that all a poet needs to do (or not do, in the case of Stoner, who is suffering from a decade-long case of writer’s block) is to write it all down. These poets not only recite their own, and one another’s, poems from memory; they seem to invent poems as they go along, while they speak in everyday life. When the poets insult one another, when Robert wrestles Ted to the ground and twists Ted’s arm until it breaks, when Ted rapes his wife Sylvia amid the spinach and mashed potatoes on the kitchen table, they do it all in free verse.

This second premise is, of course, preposterous. But it frees the playwright to write virtually all of the dialogue of her play in the clotted and gnarled diction of modern poetry that brilliantly parodies her various models. And it liberates her to depict the mundane world of college classrooms, birthday parties, bedrooms and kitchens as a world supercharged with attitude, and with words and words and words.

We first meet Ted and Robert in the first scene of the play as they meet one another on a radio program, where we learn that they are both crassly egotistical macho creeps crippled by sexual performance anxiety. We first meet Sylvia and Anne in the second scene of the play as they meet one another in a hospital psycho ward after their respective suicide attempts. And that turns out to be all we need to know about any of them. Ted lures vulnerable women into his self-serving chthonic rituals. Robert rails and accuses and abuses. Anne exploits her long-suffering husband and daughter before running off with Robert to serve as his “undermyth.” And Sylvia dwindles into a wife, engages in imaginary dialogues with the equally psychotic ghost of Emily Dickinson (Sally Mercer) and struggles with writer’s block, until she finds her voice and scores a Sylvia Plath-like triumph with a feminist bestseller.

It’s all far enough away from the real Plath, Hughes, Sexton and Lowell that we can accept, counter-factually, that all four hung out together at the edge of a woods in New England, that Anne was “Daddy Bob’s” lover, etc. But it’s all close enough to the real-life models that we just know that it will end with Anne and Sylvia finally succeeding in committing suicide. Indeed, everyone ends up just as we expected they would, which is pretty much where they began: the men are Pyrrhically triumphant, and the women, with the men’s complicity, finally succeed in doing away with themselves (Anne, swan-like, dying in song). Ted, like Orpheus, is virtually torn apart by maenad-like feminists; and Robert acknowledges that “the girls are in the ground,” but, unlike Orpheus, decides to let them be.

As we are first getting to know the characters and their neuroses, Freed’s play is great fun: fizzy, disturbing, verbally brilliant, neurotically madcap, delightfully repellent. The comedy sparkles; the poetry, and the characters’ facility with it, astonish us. Blanka Zizka’s staging (aided by Russell H. Champa’s lightning-flash lighting of Anne C. Patterson’s set, textured like a cantaloupe-rind) is breathtaking. And all of the actors have just the right amount of appeal to make us like their loathsome and pathetic characters: Smith gets Ted’s sexy smarminess, Esterman Anne’s blindsiding egocentricity, Marchetti (who repeats the role he originated in the play’s premier production in Washington) Robert’s medication-soggy late-life despair, and Pietropinto Sylvia’s alternating panic and rage.

But once the characters settle in with one another and start fucking each other over, literally and figuratively, it all gets more grim, and the play has nowhere to go except to wait for the women to meet their psychotic destinies. And all that poetry starts to doom the play as much as it dooms the characters: the characters’ poetry no longer expresses their lives, but imprisons them in a world of words that are as nasty and as self-serving as their attitudes.

Finally, the most sympathetic character of all becomes Sylvia, not because of what we know about the real-life Plath having become a feminist martyr, but because she’s the only one of the four who, for a time, stops talking poetry. “I know all about hell,” she tells Ted, once she has stopped writing and spends all of her time in the kitchen cooking soufflés. “Then fucking write about it!” he screams back.

The play’s biggest tragedy is not how people express their psychotic angst through poetry, but when they find they cannot, when the characters’ and the play’s own verbal eloquence fails. Once they get their poetic voices back we no longer trust it, and the play never recovers. 5.21.1998

Philadelphia Inquirer, Clifford A. Ridley – At some point in Amy Freed’s The Psychic Life of Savages, which concludes the 1997-98 season at the Wilma Theater, I started thinking of Tom Stoppard.

In an important sense, that’s a compliment. Savages, you see, is propelled in large part by parodies of 20th-century poetry – and not just any old 20th-century poetry, but that of four writers with exceptionally distinctive and idiosyncratic voices: the Welshman Ted Hughes and the Americans Sylvia Plath, Anne Sexton and Robert Lowell.

It takes a discriminating ear to send up this kind of material, not to mention a subtle, wicked wit and a command of language approximating that of the language merchants being dissected. Stoppard, of course, is a past master at this sort of thing, but Freed is no slouch either. While deftly magnifying the seeds of pretension and obsession in her subjects’ work, she respects the difference between satire and burlesque. The result is often very funny, both as a sendup of art and a bemused view of artistic temperament.

But that’s not the only reason I thought of Stoppard, for The Psychic Life of Savages is up to another of his tricks: Like Travesties, it assembles its dramatis personae for interactions they never had in life. Granted, Freed doesn’t call her characters by their historical names; her Hughes is Ted Magus, her Lowell is Robert Stoner, her Sexton is Anne Bittenhand, and her Plath is Sylvia Fluellen. (I assume there must be a reason why this character has a Welsh surname even though she’s Jewish, but I don’t know what it is.)

Granted, too, that the roles aren’t meant to be replicas but composites, incorporating both pure imagination and suggestions of other real-life poets. (The Hughes/Magus character, especially, sounds quite a lot like Robert Bly.) For all this, though, you can’t meet up with these people without thinking of their primary models – just as you can’t encounter the white-robed ghost named Emily, a sort of mentor to Sylvia, without thinking of that other Emily who wrote poetry in New England. I’m not sure if the real Emily was as horny as this one (“Take me, somebody! I’m not busy!”), but, as played with great gusto by Sally Mercer, this one is altogether endearing.

Anyway, I thought of Stoppard because, having tossed these psychologically disturbed folks into the same stewpot, I suspect he’d have established a tone that would serve as a clue to how we should read them. Freed, unfortunately, has not. Although The Psychic Life of Savages takes place in and around New England (on a splendidly mottled unit set by Anne C. Patterson) during a year into which the playwright has collapsed much of the cultural history of the ’50s, ’60s and ’70s, its characters remain trapped in a limbo between reality and lampoon.

Quite a lot happens to them, to be sure. Sylvia and Anne, both suicidal, meet in a mental institution; Bob and Ted meet on a literary interview show. (The show is wonderfully funny; so is the scene when Sylvia and Anne discuss suicide as if talking about cookie recipes.) Sylvia becomes Ted’s student and marries him; they all get together at Bob’s birthday party, where Anne rescues Bob from under a table and, with his wife’s blessing, takes up with him. Sylvia has writer’s block; so does Bob. Sylvia, after an empowering vision, writes her masterpiece. They all fulfill their respective destinies, which are not pretty. End of play.

This is a lot of incident, yet it lacks a sense of internal urgency that would give the audience a stake in the play. I laughed a lot at The Psychic Life of Savages – whose title, incidentally, is from Freud. But I wanted to feel involved with it as well, and I couldn’t do so because, although Freed deftly establishes her characters’ neuroses, egos, and overall ineptitude at living, she fails to do the same for the sensitivity, vision, passion and courage that impel them to make art despite their personal demons.

The problem, in other words, is an imbalance of tone – not an excess of laughter, but a failure to locate, amid the laughter, a sense of crazy dignity that doesn’t override the prevailing foolishness but coexists with it. Inasmuch as Savages is essentially a serious play, even a tragic one, this is a major problem.

The Wilma production is generally fine, with buoyant direction by Blanka Zizka and first-rate performances by T. Ryder Smith as Ted, Will Marchetti as Bob, Laura Esterman as Anne, and Rita Pietropinto as Sylvia, the least comic of the quartet. There are fine supporting performances, too, notably by Mercer and Maggie Siff. The poetic lighting is by Russell H. Champa. 5.15.1998

[previous] [next]