Photos by Ruth Sovronsky

Above: video screencaps

Excerpts from the reviews

Full reviews are below

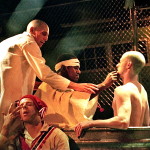

“A startlingly violent and visceral production. . . . T. Ryder Smith is fearless as the Marquis de Sade.” Raven Snook, TimeOut NY

“The last man standing in Peter Weiss’ play is the Marquis de Sade, and for the Classical Theatre of Harlem’s brawny, caged Marat/Sade he’s played with ghoulish elegance by T. Ryder Smith . . . CTH presents the first major production of the Tony Award-winning play in 40 years, and they get at the show like they were making up for lost time. Crisp, lurid leads and a trimmed text keep the political philosophy hot and lean as the projecting stage fills and empties with four-dozen Charenton asylum inmates and guards—Sade’s intimates during his final decade. When off-stage, the nutcases lurk in fenced wings at the audience’s backs, scaling and rattling the dividing metal into an industrial soundscape punctuating Richard Peaslee’s songs (piped through a tinny loudspeaker). If CTH got only one thing right, it would be Marat/Sade’s sound: soliloquies underpinned by humming loonies; Charlotte Corday (Dana Watkins) dragging the fatal stiletto along the fence; scenes of mayhem that brim the auditorium into a pitched sonic frenzy killed by shrill whistles and blasts from a crowd-control hose. But director Christopher McElroen gets plenty right . . . ” Alan Lockwood, NY Press

“McElroen stages the violence, but he never gets around to the thinking. Brutal, loud and messy, the production emphasizes the nihilistic idea that we’re all in a madhouse of corrupt leaders; attempts to overthrow them will only reveal our own savagery. . . . T. Ryder Smith is a menacing Marquis de Sade.” – Mark Blankenship, Variety

“A harrowing experience, a reminder that the theater is not always a safe place . . . the production’s only real flaw is that the text is somewhat overwhelmed by raw outpourings of primal emotion. . . . Eric Walton’s adroit Herald too often delivers the rhymes with the air of a jingle, letting them flow prettily but shrugging off their significance. Similarly, T. Ryder Smith’s Sade fails to delve into his words fully, and his philosophical debate with Marat (Nathan Hinton) thus takes a back seat to the chaotic violence it precipitates. This blunting of a sharp instrument obscures the piece’s topicality . . .” – Anna Midgette, New York Times

“Sensitive souls were well-advised to take a pass on the Classical Theatre of Harlem’s staging of Marat/Sade, which I was lucky to see yesterday, on the last day of its run: It featured the most realistic shit I’ve ever seen on a New York stage—as opposed to the shitty realism one sometimes encounters at the Roundabout or MTC. . . . the action [took] place in a central ring enclosed by chain-link fences; the audience sat in two rows on three of the sides, with two lateral galleries allowing the actors to roam behind the spectators. Since Marat/Sade happens in the titular asylum, this entirely made sense, creating the suffocating impression to be prisoner in a pressure cooker. . . . The high dramatic point comes during Sade’s big speech—which T. Ryder Smith, as the divine Marquis, must give while getting flogged, his white shirt sprouting crimson flowers. Once that’s over, he grabs handfuls of excrement from a bucket and smears it all over his face. . . .” Elizabeth Vincentelli, The Determined Dilletante blog

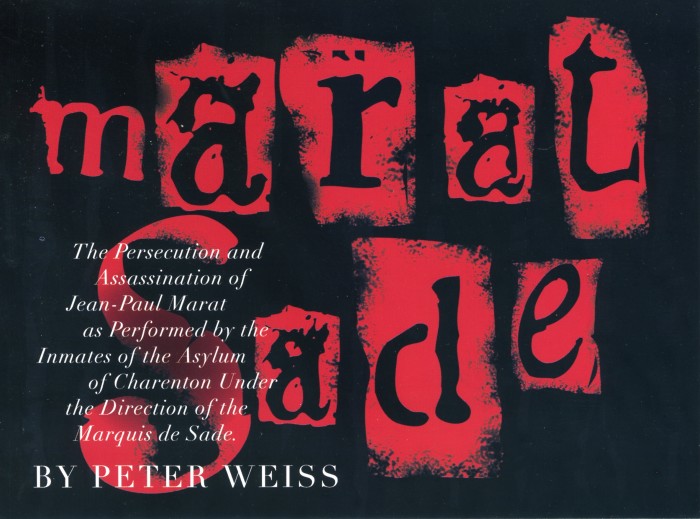

Publicity

Full reviews

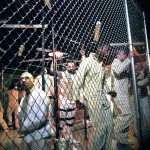

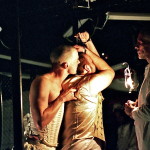

Newsday, Sam Thielman – The Marquis de Sade funhouse. On a raised stage enclosed by chain-link fence, perhaps a dozen men are dressing. Some are squeezing into women’s clothes, some are donning cobbled-together military or formal wear. One is bandaging his head; another is muttering political jargon as he wanders around the nausea-green floor, staring out at the audience. The stage is a square within a square, creating a track around the caged men, where the audience sits. Along the outside of the track, another large group of men stand, muttering or yelling, running metal rings along more chain-link. The warden (Ron Simons) sets the scene: the French asylum of Charenton, in 1808, where theater is therapy. He introduces us to the director of the evening’s entertainment (T. Ryder Smith), an angular, dead-eyed inmate wearing a regulation white jumpsuit and a formal-looking lab coat. This is the Marquis de Sade. With obsessive attention to detail and brilliant design choices, director Christopher McElroen and his crew have created the impression of going to hell to meet the devil in the Classical Theatre of Harlem production of Peter Weiss’ “Marat/Sade.” English director Peter Brook, who oversaw the definitive production of the show in 1964, would be proud of this revival. “Marat/Sade” has a thin narrative about a revolutionary stabbed in the bathtub, but mostly it’s an excuse to deliver philosophy in an immersed theatrical world. Aaron Black’s lighting design is a standout (shaded incandescent lights that the actors pull from the air; fluorescents mounted at disturbing angles; bare bulbs swinging on power cords). So is Kimberly Glennon’s nuthouse-chic costume design. That said, immersion is not necessarily a pleasant experience, as the Divine Marquis demonstrates by pouring a bucket of filth over his head. “Marat/Sade” presents upsetting images, mostly metaphors for various political stances. Inmates vomit on one another to explain depravity; guards spray inmates with a hose to illustrate oppression, and the performance culminates in a very realistic, anarchic riot. All this intensity has the curious effect of separating most of the audience into two factions: first, the people who have seen another staging of “Marat/Sade” or watched the film (also directed by Brook) and hope to catch some souvenir shrapnel (“I got sprayed by the firehose!”); and second, those who thought they were going to a more traditional play. One man apologized to his terrorized date on the way out; a woman said to her friends, with a big smile, “Well, that was fun!” Presumably, anyone who finds aggressively political theater fun is secure in the knowledge that he or she is above reproach, and experiences the performance with the same level of sophistication as someone on a roller coaster. Who knows what the frightened couple thought? Both those responses are a shame, because the play has something useful to say. Ryder’s majestic Marquis (theatrically true if not literally: de Sade was short, morbidly obese and, by 1808, pushing 70) surfaces in this sea of horrors to tell us about evil, and the love of life beyond the love of ideals. These timely sentiments are partially lost within the innovative spectacle. But “Marat/Sade” remains something to be grappled with, if only by a few who aren’t too self-satisfied to notice, or too quickly repelled. 2-16-07

Curtain Up, Jenny Sandman – “Starting with its title, everything about this play is designed to crack the spectator on the jaw, then douse him with ice-cold water, then force him to assess intelligently what has happened to him, then give him a kick in the balls, then bring him back to his senses again”.— Peter Brook. Peter Weiss’s Marat/Sade is one of those plays that can change your life—if done correctly. Peter Brook’s seminal production of the play in 1966 is considered the gold standard. Classical Theatre of Harlem’s production has come close. At the time of its production in 1966, Brook (in a homage to Brecht known for his “theatre of alienation”) was looking for a play that would break down the barrier between the theatre and the outside world. Marat/Sade manages to be both Brechtian and Artaudian (“theatre of cruelty”). It’s a multi-layered theatrical tour-de-force and a bloody and unrelenting depiction of human struggle and suffering. The play within a play structure demands the audience to play a role, as well as the actors. The inmates of the Charenton Asylum in France are performing a play in 1808 written and directed by the Marquis de Sade (then an inmate) about the killing of French revolutionary Jean-Paul Marat in 1793. The director of the hospital, Coulmier, supervises the performance, accompanied by his wife and daughter. He supports the post-revolution government led by Napoleon, and believes the play to be an endorsement of contemporary political views. The inmates, however, have other ideas, and intentionally deviate into previously suppressed lines or personal opinion. At the very end of the inmates go berserk and stage their own revolution against their keepers. The play takes place in three different time periods (1808, 1793, and the present), and in three different places (Marat’s house, the bathhouse of the lunatic asylum, and the stage itself). The audience, then, is the audience both of Marat/Sade and of the 1808 performance. There is no linear plot building toward a traditional climax, just an unfolding montage of different episodes. The main focus is on the intellectual friction and debate between Marat and de Sade. The action, such as it is, builds to the murder of Marat, but Marat/Sade is really about subjugation and revolution. And it’s all in rhymed verse! Classical Theatre of Harlem’s production maintains a fever pitch. It’s a difficult work to do right. Te temptation is to let the natural insanity of the asylum inmates overpower the revolutionary ideas they are trying to express. But the genius of the play is that it pits revolutionary ideas of freedom and democracy against human limitations. Ultimately, the grand ideas spin into chaos and the inmates lose control of themselves and their message—much as all revolutions begin with grand ideas and then spin into chaos. CTH’s asylum is a chain-link cage set around a white tile floor, festooned with flickering fluorescent lights. Two pits hold water hoses and restraints. A steel bathtub holding Marat is mounted on a swiveling platform in the middle of cage with the audience is seated around three sides of it, with more steel caging behind them. The inmates (and there are a lot of them (more than forty actors in a very small space) fill both the cage and the area behind the audience, literally surrounding them.

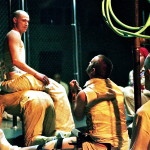

As the backdrop for madness and revolution, the set is both unrelentingly oppressive and very effective. The dominant colors are gray and white. The inmates are all dressed in white institutional uniforms and their heads are shaved. They roam around this bleak setting, led by warders and de Sade — on crutches, bandaged and straitjacketed and obviously mad. The play is technically a musical, though it’s not like any other musical you’ve ever seen. The songs are set to tinny recorded music and the inmates clearly have no natural singing ability. As there are no female inmates, some attempt to sing in falsetto. T. Ryder Smith gives a perfectly pitched performance as de Sade. He is an imperious, dissolute nobleman who may be completely mad or who may be completely sane. He rules the production with an iron fist, but at the same time, allows the inmates to periodically spin out of control. He could stop them if he wanted to, but instead he prefers to watch. You see, he wants this play to be a celebration of insanity. The one scene in which he allows his natural proclivities to get the better of him is terrifying and disturbing and the only time we see de Sade not in complete control of himself. (De Sade’s writings, which advocated extreme personal and sexual freedom unrestrained by morality, religion or law, led to the term sadism. Though never convicted of any crime, he spent 29 years in a series of prisons, including the Bastilleand insane asylums, where he did most of his writing which included his infamous “Sex without pain is like food without taste.”). The ensemble performances are marvelous. It’s easy to play the inmates as stumbling, drooling spastics, but these actors imbue their characters with far more humanity than their situation would suggest. The choreography is perfect: the cage, a swirling mass of people, never allows the audience a central focal point, but never obscures the scene at hand. There’s a collective air of hopelessness crossed with ebullience, with the word “freedom” inciting a shouting frenzy. However, as de Sade says, “My patriotism is bigger than yours.” Like the mob of the French Revolution, the inmates’ only voice can be collective. Dana Watkins as Marat’s killer, Charlotte Corday, is the most vulnerable and so the most memorable of the inmates. The production is full of fever and passion and disorder, and the most disturbing thing about it is that it’ seems so familiar. The incendiary political ideas of the French Revolution are ones to which America is fiercely committed, but it’s easy to forget that these ideas were born in a bloodbath and the Reign of Terror,— that almost all recorded political revolutions have ended in chaos. Seeing the inmates preaching equality and freedom ( though many probably don’t understand one word they’re saying), then singing, “What’s the point of revolution without general copulation?” brings thoughts that revoution spawned America, born of a revolution, has always skirted the edge of chaos and mobocracy. As de Sade disdainfully reminds us with a single look at the very end of the play, e are more like the inmates of Charenton than we’d like to admit. 2-15-07

NY Press, Alan Lockwood – The last man standing in Peter Weiss’ play is the Marquis de Sade, and for the Classical Theatre of Harlem’s brawny, caged Marat/Sade he’s played with ghoulish elegance by T. Ryder Smith (Thom Pain). Today, Sade’s acerbic, nihilistic rationale may be the French Revolution’s most recognizable voice, but we also recall Jean-Paul Marat—the Revolutionary ideologue in the iconic portrait, slumped in the bath with swathed head and a death grip on his assassin’s note. CTH presents the first major production of the Tony Award-winning play in 40 years, and they get at the show like they were making up for lost time. Crisp, lurid leads and a trimmed text keep the political philosophy hot and lean as the projecting stage fills and empties with four-dozen Charenton asylum inmates and guards—Sade’s intimates during his final decade. When off-stage, the nutcases lurk in fenced wings at the audience’s backs, scaling and rattling the dividing metal into an industrial soundscape punctuating Richard Peaslee’s songs (piped through a tinny loudspeaker). If CTH got only one thing right, it would be Marat/Sade’s sound: soliloquies underpinned by humming loonies; Charlotte Corday (Dana Watkins) dragging the fatal stiletto along the fence; scenes of mayhem that brim the auditorium into a pitched sonic frenzy killed by shrill whistles and blasts from a crowd-control hose. But director Christopher McElroen gets plenty right, including a wily, bell-ringing herald (Eric Walton) and Rajendra Ramoon Maharaj and Denise Hurd’s bevy of choreographic effect. Art with a political agenda seldom dates well, but with Marat (Nathan Hinton) extolling the good of war amid Sade’s theater of lunacy, when the word “freedom” rings out, it sounds more like Rage Against the Machine than, say, a State of the Union speech.

Time Out NY, Raven Snook – There’s no question that the world is going to pot, but anybody calling for a revolution should first experience the Classical Theatre of Harlem’s exhilarating, depressing, mostly male revival of Marat/Sade. Peter Weiss’s 1963 play about a motley collection of psychiatric inmates performing a burlesque under the direction of the Marquis de Sade in 1808 has never been for the faint of heart. CTH’s production is startlingly violent and visceral, with the audience literally surrounded by the prisoners who are (thankfully) caged. Yet that doesn’t prevent them from getting right up in your face: You can actually feel their breath as they stare you down from the other side of the chain-link fence. Although the plot of the play within the play recounts the assassination of Jean-Paul Marat, a key player in the French Revolution, the real story is the uncontrollable anger of the captives, who feel that the country is just as wretched as it was before the fall of the Bastille. Marat (Nathan Hinton) and Sade (T. Ryder Smith) engage in heated debates, comparing their dueling but equally ferocious personal philosophies as the prisoners sing, dance, scream and explode around them. Smith is fearless as the Marquis, inciting his fellow captives to whip him and cover him in feces. The finale—a brutal rape and murder—is particularly tough to stomach. “Freedom!” is a constant refrain throughout the show, but you leave the theater feeling more oppressed than ever.

The Determined Dilettante blog, Elisabeth Vincentelli – The filth and the fury. Sensitive souls were well-advised to take a pass on the Classical Theatre of Harlem’s staging of Marat/Sade, which I was lucky to see yesterday, on the last day of its run: It featured the most realistic shit I’ve ever seen on a New York stage—as opposed to the shitty realism one sometimes encounters at the Roundabout or MTC. It boggles the mind to think that not only was Peter Weiss’s play (full title: The Persecution and Assassination of Marat as Performed by the Inmates of the Asylum of Charenton Under the Direction of the Marquis de Sade) once on Broadway, but it won four Tonys in 1966! Glenda Jackson, who played Marat’s assassin, Charlotte Corday, was nominated for Best Featured Actress but didn’t win. Director Peter Brook also handled the movie adaptation, from which the photo above is taken. Except for one silent role, there weren’t any women in Christopher McElroen’s staging for CTH. And this is the least of his conceptual touches. McElroen’s biggest stroke of inspiration was to reconceive the physical space so that the action would take place in a central ring enclosed by chain-link fences; the audience sat in two rows on three of the sides, with two lateral galleries allowing the actors to roam behind the spectators. Since Marat/Sade happens in the titular asylum, this entirely made sense, creating the suffocating impression to be prisoner in a pressure cooker. And McElroen ratcheted up the tension already present in the text, keeping the proceedings at a fever pitch the entire time. The high dramatic point comes during Sade’s big speech—which T. Ryder Smith, as the divine Marquis, must give while getting flogged, his white shirt sprouting crimson flowers. Once that’s over, he grabs handfuls of excrement from a bucket and smears it all over his face. A woman sitting in front of me laughed loudly, and was told “This is not funny!” (I couldn’t identify who said that—a fellow audience member or someone from the cast.) Sitting a few feet away and watching in horror as turds were flying about, I felt as if a huge weight was pressing down on my chest. My main caveat with the whole endeavor is that too often Weiss’s text—which essentially contrasts two ideas of revolution, Marat’s radical dream of a revolution by the people and for the people and Sade’s highly individualistic philosophy—got lost in the general mayhem (we’re talking hoses to calm down the inmates here). Weiss was a leftist German who in the 1960s realized socialism as practiced by the USSR—one of two large-scale models of communism in action at the time—could not work without crushing the individual. (See also Vasily Grossman’s extraordinary Life and Fate for the daily practice of Stalinism.) “On the one hand the urge with axes and knives/To change the whole world and improve people’s lives/On the other hand the individual lost in thought/Caught in the throes of the calamity he’s wrought,” summarizes Sade. But it’s hard to focus on ideas when someone is banging on a pipe right behind your head or pulling on your chair. As we embark on presidential campaigns in France and here, those of us passionate about the arts should keep in mind something else Weiss wrote (not in Marat/Sade): “Art is never a weapon in the sense of concrete political action. It only conveys activity, it communicates qualities which we have to detect in ourselves. We are the ones who, upon closing in on a work of art, liberate the powers confined within. Without our ability to ingest, our own ability to think, the work remains powerless. However, with our attentiveness we transpose the latent vision into real, perceptible deeds.” Partly this is saying that going to a political show—writing a political show—just isn’t enough when it comes to “concrete action.” Let’s keep this in mind when do-gooders start going on and on about the importance of political art: As much as I’d like to think otherwise, art will never replace the less-glamorous practice of politics when it comes to actually changing the world. You can go listen to Springsteen and feel good about yourself, but that won’t prevent Rome from burning—ie, the Republican machine from savagely gutting your country’s institutions, moral fabric and individual lives. 3-12-07

Show Business, Rebecca Jones – The Persecution and Assassination of Jean-Paul Marat as Performed by the Inmates of the Asylum of Charenton Under the Direction of the Marquis de Sade, better known as simply Marat/Sade, is a production that requires cacophony and chaos. Fortunately, the Classical Theatre of Harlem’s revival holds nothing back. In this play-within-a-play, as aptly described by its full title, the patients of Charenton mount a play about the death of French revolutionary Jean-Paul Marat, written and directed by fellow patient the Marquis de Sade. The inmates’ production is attended by the director of the hospital, Coulmier, and his wife and daughter. Written in 1963, but set in 1808 at Charenton and 1793 within Sade’s play, this orgy of insanity and philosophy takes its audience far beyond 2007, forcing us to confront more difficult topics than seems fair for a single show. Director Christopher McElroen takes full advantage of the shock value of the piece, milking each moment for all it’s worth, while still managing to display a delicate subtlety that wrenches the heart even when the brain can no longer assimilate the images composed on the perfectly crafted set (flawlessly designed in the round by Troy Hourie).

With little pretense of advancing the plot, Marat/Sade presents a facile debate between Sade and his own character, Marat, which deconstructs the concepts of equality, freedom, class, and the entirety of the socio-politico-economic infrastructure. The interior play relates specifically to the events of the French Revolution, but Coulmier reacts vociferously against many statements that touch too closely on arguments of his own time. “We’re all revolutionaries these days, but this is treachery!” he exclaims, after a remark questioning authority in general. Coulmier’s hypocrisy is blatantly ridiculous, but the deep chords Sade and Marat touch in their arguments allow nothing on stage to be taken as trivial.

It is impossible to single out any one performance for its brilliance, as the entire ensemble performs seamlessly together, building off each other’s energy into a hypnotizing frenzy. The whole cast demonstrates a haunting level of commitment and intensity. The arresting visuals are aided by Aaron Black’s raw lighting design, using entirely white light that glares off the white costumes of inmates and doctors. It is difficult to present something truly unique in the contemporary theater, but the twists and turns of McElroen’s production are shockingly unexpected.

BroadwayWorld.com, Michael Dale – Marat/Sade: Cage Match. The stony-faced fellow standing at the auditorium’s entrance pays little attention to the inquiries of the crowd of ticket-holders in the lobby asking when the house will open so they can take their seats. No, he’s not a rude usher. He’s really an actor playing an asylum attendant in The Classical Theatre of Harlem’s thrillingly disturbing environmental production of Peter Weiss’ The Persecution and Assassination of Jean-Paul Marat as Performed by the Inmates of the Asylum of Charenton Under the Direction of The Marquis de Sade, better known by the abbreviation Marat/Sade. When an unseen person on the other side instructs him to let us in, we’re told to quickly take any seat available. Set designer Troy Hourie has filled the space with a steel cage, which is filled with more than thirty members of director Christopher McElroen’s excellent acting ensemble, most of whom play mentally disturbed inmates. Some are naked as we enter, being subjected to the forceful orders of attendants instructing all to put on their clothes and silently take their places. One poor fellow, seeming unaware of anything, stands limply hanging from the pole he is chained to, eyes upward and a secretions dripping down from his mouth and nose. He spends the entire intermissionless hour and forty-five minutes that way. The audience sits in two rows of folding chairs that encircle the cage. Behind them on two sides are auxiliary cages used to keep inmates who are acting up or not needed presently. Marat/Sade is not your typical Tony-winner for Best Play. Its Broadway premiere, a transfer of director Peter Brooks’ 1964 West End production, was both revered and ridiculed, exhilarating those who shouted its praises while sickening others who walked out of performances. (The joke of the day was, “Have you seen Marat/Sade?” “No, but I read the title.”) The piece is primarily a play within a play, being presented at the Asylum of Charenton in France; an institution known for its humanitarian treatment of inmates under director Abbe de Coulmier (Ron Simons). It is 1808 and Coulmier, believing in theatre as therapy, has arranged for his most infamous inmate, The Marquis de Sade (T. Ryder Smith), to write an direct a play performed by his patients in patriotic salute to the revolution that has placed Napoleon at the head of the government. De Sade’s drama tells how aristocrat Charlotte Corday (Dana Watkins) from a less-violent revolutionary faction, came to murder journalist Jean-Paul Marat (Nathan Hinton), a key figure in The Reign of Terror who spent most of his time soaking in a bathtub because of a skin condition. There are songs composed by Richard Peaslee, with lyrics by Adrian Mitchell, who supplies the English translation to Weiss’ original German. But the play isn’t exactly the thing here, as the patients are prone to ad-libbing outbursts about their own need to revolt; their violent rebellions calmly observed by de Sade. Fight choreographer Denise A. Hurd has some convincing moments, while Rajendra Ramoon Maharaj’s choreography features stylized sexual acts. With actors only inches away from the front row audience members, and not much further away from the rest, you’ll no doubt find yourself an up-close witness to many violent acts and, during calmer moments, be subjected to the curious stares of inmates who may look you directly in the eye or right through you. Smith is very effective in the play’s centerpiece moment, which involves whipping, bloodshed, masturbation, urine and excrement. (All of it fake, of course.) Marat/Sade is a rather ambiguous drama, perhaps most effective in its mere depiction of lust and cruelty. The Classical Theatre of Harlem’s production is an intriguing piece of human spectacle.

New York Times, Anna Midgette – The chain-link enclosure occupies most of the room. It is filled with naked men. They struggle to put on their clothes, muttering to themselves, barely kept under control by three tough guards. The audience is seated all around the central enclosure; those at the sides are trapped between it and two holding pens at either side of the room. As the evening continues, the men erupt, hurling themselves against the mesh, inches from the onlookers’ faces and backs. There is spit, and realistic-looking vomit and feces. The hoses that the guards use to restore order spatter the spectators with antiseptic-smelling water. Watching the new production of “Marat/Sade” that opened on Thursday night at the Classical Theater of Harlem was a harrowing experience, a reminder that theater is not always a safe place. It’s a reminder, period. Peter Weiss’s play “The Persecution and Assassination of Jean-Paul Marat as Performed by the Inmates of the Asylum of Charenton Under the Direction of the Marquis de Sade,” familiarly known as “Marat/Sade,” was published in 1963 and won four Tony Awards (in Peter Brook’s Broadway production) in 1966. This new production, by Christopher McElroen, is a throwback to a 1960s spirit of radicalism and transgression (and, further back, to Antonin Artaud’s Theater of Cruelty). Mr. Weiss’s play questions whether revolution can truly achieve lasting change; Mr. McElroen’s production tacitly questions how lasting were the aftereffects of the artistic revolutions of the ’60s. All these years later, nudity and bodily effluvia still feel shocking.

Mr. McElroen’s is an all-male asylum; in Sade’s play, men take the women’s parts. (Dana Watkins is a strapping Charlotte Corday; David Ryan Smith, a powerful Rossignol.) This makes dramatic sense except that it renders especially dubious the decision of the asylum director, Coulmier (played by Ron Simons as a perfectly self-satisfied arriviste), to take his wife and daughter with him into the enclosure to watch the show. But the production’s only real flaw is that the text is somewhat overwhelmed by raw outpourings of primal emotion. Ideally, an actor’s reading of rhymed verse creates a kind of counterpoint that uses the rhymes as a point of reference; here, Eric Walton’s adroit Herald too often delivers the rhymes with the air of a jingle, letting them flow prettily but shrugging off their significance. Similarly, T. Ryder Smith’s Sade fails to delve into his words fully, and his philosophical debate with Marat (Nathan Hinton) thus takes a back seat to the chaotic violence it precipitates. This blunting of a sharp instrument obscures the piece’s topicality. “Marat/Sade” is no less relevant today as a diatribe against inadequate leaders who manipulate their people into complacency. At the end, a revolution takes place within the central cage, leaving the floor strewn with clothes and bodies. Outside the enclosure, the spectators sat in silence, uncertain how to react. After a while, they all got up and went about their business. 2-20-07

New York Times’ reader’s reviews:

harrowing and haunting, March 12, 2007 Reviewer: rbb1787. I saw this production on 10 March, the night before it closed, and I will never forget it. It was harrowing and haunting — casting doubt on the utility of revolution, on the distinctions between sanity and madness, order and tyranny, liberty and license. The acting throughout was amazing — Sade, Marat, the director of the asylum, and the Herald.

unique, March 04, 2007 Reviewer: landau38. I am grateful to the Classical Theater of Harlem for letting me experience this piece—I had not seen it for over forty years, and had forgotten how passionate a play it truly is. The play is full of contradictions—that is one of its fascinations, and this production allows you to understand all of them. I did not agree with all of the director’s choices, but the strongest moments of the play are truly riveting. I left the theater feeling very exhilarated. Marat’s Revolution For Our Time, February 17, 2007, Reviewer: rsovronsky. The latest production of Marat/Sade at the Classical Theatre of Harlem features of cast of over 40 men in the roles of the inmates of Charenton, an asylum that houses the Marquis de Sade who directs the inmates in plays as a form of therapy. The audience is confined within the asylum, separated from the ‘inmates’ by a chain link fence that brings them within inches of the explosive violence and rage that lurks just beneath the surface. The “play within the play” enacts the murder of revolutionary Jean-Paul Marat by a young nun, Charlotte Corday, who came to kill Marat to bring an end to his policies that called for hundreds to die at the guillotines. This powerful performance portrays the stark violence of our society and the painful differences between the “haves” and the “have nots” that have existed throughout human history. The staging and set design of this production leave nothing to the imagination, and brings the audience face to face with a world gone mad. It is a production that should not be missed.

Village Voice, Andy Propst – Don’t get too used to the civility that precedes Christopher McElroen’s revival of Peter Weiss’s Marat/Sade. After you’ve been greeted by a well-heeled trio outside the theater, you’re plunged into the Asylum of Charenton where the inmates are preparing to present a history of French revolutionary Jean-Paul Marat as written by the Marquis de Sade. Behind chain-link fencing, the all-male cast, many nude, don institutional jumpsuits. It’s clear you’re in for a wild ride with this sprawling philosophical play that provides few answers for the questions it raises about the nature of man and revolution.

In actuality, the philosophical debate of Marat/Sade becomes secondary to McElroen’s hyper-kinetic environmental staging, which undeniably pays tribute to Peter Brook’s original. As inmates are hosed down, vomit flows, and at one point Sade (T. Ryder Smith) smears himself with what appears to be feces. McElroen brings the brutality of the asylum—and by extension the brutality of our world—to life. But there’s a cost: Often, neither Smith nor Nathan Hinton’s Marat can be heard, particularly as inmates scream and rattle the fence. Ultimately, exhaustion sets in, and you begin to long for the interruptions from Eric Walton’s commanding Herald, who, as narrator, manages to restore some much-needed decorum to what should not only be visceral, but intellectual, proceedings.

OffOffOnline, Frank Episale – Prisoners and Players. The assault on the audience came almost immediately upon entrance to the theater. As we squeezed our way into the tightly packed seats, large men, several of them naked, glared at us while they finished getting dressed under the baleful gaze of armed guards. There was no way to avoid making eye contact with the prisoners, some of whom furtively poked their fingers through the chain-link structure separating them from the audience, others of whom stared angrily outward. These looks, desperate or threatening, continued throughout the performance, even while “great men” debated how best to serve “the people.” The people themselves stared out at the audience, daring us to really see them.

Peter Weiss’s dauntingly titled The Persecution and Assassination of Jean-Paul Marat as Performed by the Inmates of the Asylum of Charenton Under the Direction of the Marquis de Sade, published in 1963, is one of the genuine triumphs of 20th-century drama. Peter Brook’s seminal 1964 production by the Royal Shakespeare Company, which came to New York and won several Tonys in 1966, is widely considered a triumph as well, and has become so closely associated with the play that the two seem almost inextricable. Given the large cast, the demanding text, and the shadow of an unforgettable production, it shouldn’t be surprising that the play is rarely produced professionally, despite its importance. Still, it is something of a shock to read that Marat/Sade has not received a major production in New York in 40 years. Theatergoers should therefore not miss the opportunity to see Classical Theater of Harlem’s audacious new staging, playing now through March 11. This new production, directed by CTH co-founder Christopher McElroen, isn’t perfect, but it is both riveting and challenging. Most impressive, it is relentlessly and gloriously uncomfortable to watch, reminding us that theater is capable of a great deal more than soothingly diverting entertainment.

Inspired by a provocative piece of history, the play’s plot is evident in its title. The infamous Marquis de Sade spent the final years of his life in an asylum for the criminally insane. As a part of the progressive treatment offered there, he was sometimes allowed to write and produce plays, with the other inmates as actors. While the plays Sade actually wrote while in captivity were rather apolitical and not particularly transgressive by the period’s standards, Weiss imagines that Sade wrote a play about the assassination of prominent French revolutionary Jean-Paul Marat. As the play-within-the-play moves inexorably toward Marat’s stabbing by Charlotte Corday, it also allows time for Sade to debate his fictionalized Marat about a variety of philosophical and political issues. The play’s structure and content are complex enough to defy easy summary, and McElroen’s production stumbles when he attempts to distract the audience from this complexity. While Sade and Marat toss barbed abstractions across the stage, McElroen creates easy laughs with the spectacle of the inmates struggling to behave themselves. The moments are charming and diverting, but they take away from the seriousness of the debate under way. To be fair, Marat and, especially, Sade are given more and more focus as the play progresses. Layers of irony and absurdity are stripped away until Weiss’s severely wounded idealism is rendered in all its cynicism and vitriol. For the most part, the actors handle themselves well. Certainly T. Ryder Smith, as Sade, gives a compelling and layered performance, alternately controlled and raw. Dana Watkins deftly delivers a performance within a performance—as a narcoleptic inmate playing the murderous Corday—with a level of craft that ultimately manages to overshadow his considerable physical beauty. More impressive than the standout performances from some of the leads, however, is the commitment and discipline displayed by most of the ensemble. The images that lingered longest in my memory were not of Sade’s self-mutilation or Jacques Roux’s (Andrew Guilart) histrionics but of the haunted and haunting stares of the ensemble. The press notes for Marat/Sade do not mention the play’s political underpinnings, but even in a production that shies away from Weiss’s more cerebral tendencies, the prisoners’ despair shimmers with contemporary resonance. An inmate cries, “We talk about freedom, but who is this freedom for?” before being struck down unceremoniously by abusive guards.

Propagandistic optimism about Napoleon’s disastrous final war and the triumphant march of progress is sprinkled throughout the play. Alarmingly, it becomes increasingly indistinguishable from presidential press conferences. As the music swells and the prisoners revolt, 1803, 1966, and 2007 converge, and spectators are left to wonder whether they are to blame and whether there’s anything they can do to stop history’s cyclical march. 2-23-07

donshewey.com, Don Shewey – Wow, I really admire Christopher McElroen, the executive director of the Classical Theatre of Harlem. Like his 2003 staging of Genet’s The Blacks, his new all-male revival of Marat/Sade is a spectacular, uncompromisingly theatrical piece of work. It’s not like going to see just another show. It’s an experience from beginning to end, and it’s not 100% total joy. The set consists of chain-link fencing that creates a cage separating the actors from the audience. The audience is herded in all at once to sit on three sides in two rows, and the cage extends behind the audience, so you’re surrounded by inmates of the asylum, quiet at times, singing, going crazy. Coulmier, the attendant of the asylum, and his guests (his wife and daughter), are played by very well-dressed black actors, and at the beginning of the show they are locked into the cage with the inmates. It’s a very tense and alive experience that starts out kinda sexy — the large cast comes on in character, most of them naked, and they dress in boxers, t-shirts, and jumpsuits in front of the audience. It’s a mixed race cast, with a lot of cute young gay guys with shaved heads. But the play is a very intense conversation between the Marquis de Sade (the excellent T. Ryder Smith), who champions the individual imagination over any collective action, and the revolutionary Marat (Nathan Hinton, whose performance is the weakest in the show), who advocates violent overthrow of the aristocracy (“killing in self-defense”) and is himself assassinated. It’s also very clearly about war, with no easy answers. At the end, no curtain call — the audience sits for a very long time in silence looking at a stage area that’s been wrecked with five or six “dead”/raped/ravaged bodies lying around, and it dawns on you: we’re looking at a theatrical image of Baghdad right now. The theatermakers don’t give us any way out of dealing with what we’re feeling about that. Very powerful and disturbing. Most of us probably haven’t thought about the play since we saw it in college, or saw the movie of Peter Brook’s famous production. (Speaking of Judy Collins, we also heard the music first in her medley on In My Life) And we mostly remember it for being a shockingly experimental night in the theater, without a lot of details. But the play gives us a lot to think about. I went home and read the chapter about Brook’s original production in David Richard Jones’ Great Directors at Work (one of the best books about theater ever written), which is fascinating. Peter Brook had Adrian Mitchell create an English-language version of Peter Weiss’s German play, whose complete title is The Persecution and Assassination of Jean-Paul Marat as Performed by the Inmates of the Asylum of Charenton Under the Direction of the Marquis de Sade. Brook says, “Starting with its title, everything about this play is designed to crack the spectator on the jaw, then douse him with ice-cold water, then force him to assess intelligently what has happened to him, then give him a kick in the balls, then bring him back to his senses again.” It’s true! 2-17-07

Film Experience blogspot, Nathaniel R. – It occurred to me recently that I’ve been skimpy on the theater posts…and here I am a playgoer in Manhattan. I haven’t been attending as often as in previous years but when I have made it I’ve seen shows near the end of their runs. It’s discouraging to write about shows that none of my New York or NY visiting readers can even consider seeing. Nevertheless, I wanted to mention two I saw recently: both with film connections. They’re closing today (sorry) but I felt the urge to mention them. . . . I had better luck with the second production, which was less explicitly about modern politics but still packed a political wallop with its eery universality about crumbling democracies, war profiteering, and uprisings. The Classical Theater of Harlem is literally one block away from my best friends apartment. I have no excuse for not having been earlier. The theater often wins rave reviews. The production ending today is The Persecution and Assassination of Jean Paul Marat as Performed by the Inmates of the Asylum of Charenton Under the Direction of the Marquis de Sade but it’s more commonly known as Marat/Sade. Theater lovers will know it as Peter Weiss’ Tony winner from 1966. In the play …well, actually, why go there: the title is the plot. Movie buffs might not know the play by name, but it’ll still be familiar: it’s a piece of the narrative of Quills which starred Geoffrey Rush and Kate Winslet back in 2000.

This production is ingeniously staged in front of you in a caged of space but its production design is all around you as well (fenced off). It’s the only production I’ve ever watched through a fence but the effect was startling. You are inside the asylum. The actors mental patients are all around you. They’re disruptive. They don’t mind staring. They forget their lines. They try to jump forward to parts of the narrative they enjoy performing more. It’s all extremely disorienting but the production is absolutely committed to their communal warped headspace. If it sounds over the top, well… it is set inside of an insane asylum with a legendary provocateur as ringleader. I won’t even go into the Marquis’ mid-play monologue which contains stage business that is the most disturbing I have seen in years and which would surely bring John Waters to a standing ovation. T Ryder Smith (who was also excellent in the long running Underneath the Lintel a few years back) is the Marquis and gives a brave unsympathetic performance. He’s unafraid to play up the inherent danger in the Marquis’ manipulative persona. That’s something that eluded Geoffrey Rush in his more cartoonish portrait in the film version. But my favorite performance in the production was Dana Watkins* as an inmate attempting to portray the murderous Charlotte Corday. For all of the gimmick of the plays: watching actors playing inmates trying to perform roles entirely unsuited for them, it would be easy for character choices to get lost in the shuffle. But Watkins’s work feels fully formed and filled with range as he tries to navigate a juggling act that overwhelms him: remembering the part of this deadly woman, trying to overcome his own sleeping sickness, attempting to please the controlling Marquis and steering clear (as best as he can) of the violent inmate with whom he shares scenes. It was a stunning production of difficult material. I’ll be returning to the Classical Theater of Harlem next chance I get. 3-11-07

theatremania.com, David Finkle – The hero of The Classical Theatre of Harlem’s revival of Peter Weiss’ Marat / Sade is set designer Troy Hourie, who’s created a large chain-link cage that not only thrusts squarely into the audience but wraps ominously behind some of the crowd. The effect is to make spectators wonder whether the 30-plus actors peering through the noisy fence are the asylum inmates or whether the folks huddled in the folding-chairs are the insane ones. Weiss, who initially wowed the theater world with this highly theatrical piece in 1963, wants to drive home his contention that hope for global equilibrium is futile in a world ready to go mad at a moment’s notice. His argument is open to some debate, but there’s no denying he illustrates it explosively or that director Christopher McElroen’s production does a generally commendable job of serving the author’s incendiary purposes. At the play’s core is a reasoned discussion of the aims and misfires of revolution, the search for a precise definition of genuine lunacy, and the question of what constitutes integrated sexual behavior. The rambunctious work has some basis in the fact that the controversial Donatien Alphonse Francois, Marquis de Sade, was immured in the historic Charenton Asylum during and after the French Revolution. It’s Weiss’ fancy that in 1808, Sade (T. Ryder Smith) prepared an entertainment for asylum supervisor Coulmier (Ron Simons), his wife (Tyshawn Major), and their daughter (Joi Sears) that depicted the 1793 murder of Revolution pamphleteer Jean-Paul Marat (Nathan Hinton) by Charlotte Corday (Dana Watkins).

Intermingling the growing notion of democratic freedom with the sexual liberation he promoted, a rational-seeming Sade seizes on the opportunity to dispute Coulmier’s conciliatory politics. While allowing his masque to unfold, he runs the risk of bringing the warden’s wrath on him. He even ventures so far as to indulge in a philosophical diatribe about his beliefs that includes his being flagellated — more a masochistic than sadistic act — and his smearing himself with what looks convincing like human feces.

Coulmier never becomes more than momentarily threatening, however, and the play-within-the-play proceeds to and through the stabbing sequence carried out by a narcoleptic inmate handed a knife. (Would any asylum head allow an actual knife to be used, even with attendants close by?) Sade’s script is played out while other inmates, some of them with speeches to deliver, are alternately docile and belligerent. Often, the ensemble members raise their voices on Richard Peaslee’s songs, the best-known including the phrase “Marat, we’re poor, and the poor stay poor.” (Kelvyn Bell is the musical director and Rajendra Ramoon Maharaj is the choreographer and the likely instigator of the stylized fellatio and anal intercourse performed from time to time.)

Marat/Sade is a handful for any company to tackle. A director is charged with conveying Weiss’ intellectual ideas in an atmosphere of supposed chaos, but an occasional slip and the chaos shifts rapidly from controlled and lucid to uncontrolled and confusing. Assuming this daunting assignment, McElroen sees that the central actions come across for the most part. Every once in a while, though, this French Bedlam does devolve into bedlam. The fence rattling is excessively cacophonous, as are the actors doing the rattling. The focal figures — especially Smith’s gaunt and sinister Marquis, Watkins’ timid inmate’s impersonation of Corday, and Hinton’s exhortatory Marat — are authoritative. But too many in the company fall into the trap that snares so many actors playing the insane; they get caught up distractingly in their own take on navel-gazing.

Perhaps, though, certain productions should be judged like Olympic diving competitions, by degree of difficulty. According to that measure, let’s say that on a scale of 10, this Marat/Sade earns a 7.25. 2-16-07

Variety, Mark Blankenship – You can’t win ’em all. Whether tackling Genet or Beckett or Shakespeare, Classical Theater of Harlem’s imagination and interpretive insight usually invigorates a playwright’s vision of the cosmic repercussions carried by the performance of daily life. But the company stumbles with its revival of the meta-theatrical “Marat/Sade.” Helmer and CTH exec director Christopher McElroen gets so focused on one half of this rarely seen play that he leaves it feeling lopsided. Peter Weiss’ 1966 Tony winner for play is a fascinating hodgepodge of theatrical theories. Set in 1808 in the French asylum Charenton, it lets the Marquis de Sade and his fellow inmates stage their own play, about the 1793 murder of revolutionary Jean-Paul Marat. Watching a performance of a performance, which sometimes decays into madness, we’re asked to think about the theatricality of politics while being shocked at the inmates’ behavior.

When it premiered in Peter Brook’s production, critics hyperventilated over the play’s blend of Brecht and Artaud. Like the former, Weiss wants us to consider coolly the political arguments of both Marat, who says the people need equality to survive, and Sade, who says they crave subservience. However, the scribe also respects Artaud’s conviction that theater should be a dagger to our senses, jolting us with primal moments. “Marat/Sade’s” political rhetoric keeps exploding into riots. McElroen stages the violence, but he never gets around to the thinking. Brutal, loud and messy, the production emphasizes the nihilistic idea that we’re all in a madhouse of corrupt leaders; attempts to overthrow them will only reveal our own savagery. That theme is certainly in the play, but while Weiss entangles it with other ideas and leaves us to decide how we feel, McElroen makes chaos his moral. In a nod to Brook’s design, which staged the play behind jailhouse bars, helmer sticks his cast in a chain-link cage. We enter to see almost 40 naked male inmates dressing themselves for the show as guards with clubs stand by. Through chain-link holes and under harsh fluorescent lights, they already seem like debased animals. And there’s chain-link behind us, too. As the story of Marat’s murder gets told through speeches, scenes and songs, men often stand at our backs. They rattle the fence or mutter things in our ears, making it clear we’re all part of the great big nuthouse of society. That device can be chilling, especially when bizarre chants are sung from every direction. But the hissing and moaning are distractions when Weiss shifts his dramatic approach. He gives both Marat (Nathan Hinton) and Sade (a menacing T. Ryder Smith) complex speeches about their political philosophies. These moments provide a crucial intellectual balance to the riots, but McElroen never quiets his ensemble long enough to let us pay attention. Entire sections are incoherent because they can’t be heard over the man yelping in the corner. With the exception of Smith and Hinton, thesps also speak with unnatural inflections and cadences. That may advance the mood of mental illness, but it makes it impossible to follow the logic of, say, Charlotte Corday (Dana Watkins) as she explains her reasons for stabbing Marat in his bathtub. Since the production’s individual thoughts are incomprehensible, it only communicates generalized hysteria. McElroen tries to keep escalating the intensity — even having Ryder cover himself in (hopefully) fake feces while delivering a speech — but when there are no moments of quiet, volume loses meaning. In the theater, loud and louder aren’t really contrasts. They’re just part of the same numbing roar. 2-14-07

Newark Star-Ledger, Michael Sommers – Defeated by ‘Marat/Sade’.Harlem troupe deserves credit for tackling drama set in asylum. Milling around before guards open padlocked gates into the auditorium, the audience sees the show’s title scrawled in dripping letters across a wall:”The Persecution and Assassination of Jean-Paul Marat as Performed by the Inmates of the Asylum of Charenton Under the Direction of the Marquis de Sade.” Known for short as “Marat/Sade,” Peter Weiss’ play and director Peter Brook’s production took New York by storm in 1965. Living up to its title and based on history, these visceral doings involve lunatics acting out a drama regarding the 1793 murder in his bathtub of Marat, a bloodthirsty radical of the French Revolution. The florid play-within-the-play is composed and staged by de Sade himself, the madly kinky author locked away for his own safety. This event supposedly occurs in 1808 under the misguided patronage of the asylum director, who considers the performance so much therapy and expects de Sade’s piece to laud then-reigning Napoleon’s regime. The wildly delusional actors continually freak out, however, and despite their wardens’ brutal attempts to keep order, the show careens into chaos. Directed by Brook in “Theatre of Cruelty” style meant to shock viewers with realistic physicality, “Marat/Sade” won best play and direction Tony Awards. But due to its scope and performance demands, the work is rarely seen outside universities. Trust the adventurous Classical Theatre of Harlem to mount the challenging play at its residence in the Harlem School of the Arts, where the production opened Thursday with a 40-member company. Aside from designer Troy Hourie’s set, which situates the tumultuous action inside a huge chain-link cage at the center of the auditorium, and a few persuasive portrayals, the production doesn’t present the work that effectively. Director Christopher McElroen confusingly blurs the time frame by dressing the almost entirely male ensemble in modern-day jumpsuits and applying other contemporary visual touches. It’s soon obvious the majority of actors do not have sufficient rehearsal and/or technique to depict believably circa-1800s insane people performing — despite varying afflictions — a grandiose mix of verse, song and makeshift pageantry. Mostly they writhe, howl and rattle the cage, making menacing gestures at onlookers. Their energy is high but there’s little sense of danger — except for one point when an audience member’s cell phone went off for a second time and everybody erupted in his direction. Anyway, too much of the interior play is gabbled and diffused by the ensemble’s limitations. The boldest performance comes from Daniel Talbott as a slavering sex maniac who lunges at fellow players in the midst of his actorly posturing. A lean, curiously ascetic figure, T. Ryder Smith portrays decadent de Sade with icy reserve. As the catatonic inmate depicting assassin Charlotte Corday, Dana Watkins wobbles through the uproar like a dazed puppet. It’s great to get a chance to see “Marat/Sade” in the flesh. It would be better if Classical Theatre of Harlem had the resources to present it sufficiently. A classic case of a company’s reach exceeding its grasp, let’s at least applaud its ambition. 2-16-07

Backstage, Adam R. Perlman – Mental asylums may not yet be fashionable vacation spots, but they are choice locales for musicals seeking to excavate damaged souls. This curious canon includes not only John Doyle’s recent production of Sweeney Todd and Anne Bogart’s 1984 NYU version of South Pacific, set inside the mental ward of a Veterans Administration hospital, but also the granddaddy of all crazy-house musicals, Marat/Sade. With a provocative text by Peter Weiss and a score by Richard Peaslee that’s derivative of Kurt Weill, Marat/Sade (as its lengthy title is commonly abbreviated) arrives at its milieu not by dramatic reinvention but historical fact: The Marquis de Sade did indeed stage theatrical spectacles while at the asylum of Charenton. It’s not such a stretch to think he might have even engaged a subject as tantalizing as the Jacobin revolutionary Jean-Paul Marat, whose watery death was famously committed to canvas by Jacques-Louis David. Weiss’ script, which poses the questions that revolutions and demagogues beg, is a study in dichotomies, pitting Marat’s views on equality versus Sade’s on subservience, the grander political ends of the asylum director Coulmier against Sade’s more personal motivations, the inmates’ compulsion toward community against their devolution to solitary baseness. But while Weiss packs his prison like a pressure cooker full of aerosols, it’s always been Peter Brook’s legendary staging that made Marat/Sade an event. Much owes to Brook’s own dichotomous approach, which famously blended the script’s Brechtian songs of commentary with an Artaudian assault to the senses. Few productions stray from Brook’s impressive imprimatur, and a couple of well-conceived touches aside (particularly Troy Hourie’s set design, which features a chain-link fence that traps the cast among the audience — and the audience among the cast), the Classical Theatre of Harlem largely hews to Brook’s iconic visuals. What the theatre hasn’t carried through is the deceptively subtle balance that Brook maintained among the elements warring both within the script and the staging. Director Christopher McElroen never lends Marat/Sade the control that would reward its chaos. Moments meant to threaten gravely or even temporarily shatter the play within the play don’t register here, where separate realities combine into a lulling din. Also confused is the production’s relationship to the audience, who are implicated by the set and occasional jets from a water hose but whose role McElroen never decides. The cast is a mixed bag, but if Nathan Hinton struggles to register even the slightest flicker of revolutionary fire as Marat, T. Ryder Smith is a splendidly chilly Sade. Yet with a production that prefers rattling the cage to exploring its ecosystem, the asylum of this Marat/Sade is unusually confining. 2-20-07

New Times, Chesley Plemmons – New ‘Marat/Sade’ is violent but stunning. Under normal circumstances, Peter Weiss'”Marat/Sade,” which won the 1966 Tony Award for Best Play, is an intense evening in the theater. In the hands of a fearless director, it can be totally shattering. Christopher McElroen is just such a daring fellow, and with the help of brilliant scenic designer Troy Hourie, the Classical Theatre of Harlem’s revival of this seldom-produced drama is a knockout.

A play within a play, as well as a musical set in a madhouse, its complete marquee-challenging title is “The Persecution and Assassination of Jean-Paul Marat as Performed by the Inmates of the Asylum of Charenton Under the Direction of the Marquis de Sade.” That mouthful pretty wells sums up the plot, if not the dramatic process. Weiss’ concept puts us in the Charenton asylum in 1808, 15 years after the murder of revolutionary Jean-Paul Marat, and nine years after Napoleon ascended to the French throne. The occasion is a divertissement devised by the Marquis de Sade (T. Ryder Smith), an inmate of the hospital, for the enjoyment of Coulmier (Ron Simons), the director of this French Bedlam. In the play within a play, de Sade directs the inmates, who are mostly insane, in recreating the real-life 1793 murder of Marat (Nathan Hinton) by the disenchanted revolutionary Charlotte Corday (Dana Watkins).

Hourie’s set wraps the thrust stage in heavy chain-link fence and behind two of the three sides he has also run fence-lined alleyways where the actor/inmates gather to scream at the other actors and stare down those members of the audience unlucky enough to be in range of their penetrating eyes and grasping hands. Once Coulmier and his wife are escorted into the fenced-in playing area, which is, in fact, the hospital bathhouse, the controlled chaos begins. The inmates — nude at the start, suggesting they have they have just been hosed down — don white uniforms and assume their roles in the “entertainment.” Many of the actors have shaved heads and many are in straightjackets.

The cast numbers 40 and the scene quickly becomes one of restless caged animals.

The floor is white tile and there are pits where patients can be submerged to calm them down. In the center is a steel tub where Marat is bathing, which rotates as the bloody retelling progresses. Weiss’ play is in rhymed verse and most of the narrative is delivered by the Herald (Eric Walton), a wandering minstrel. De Sade interrupts from time to time to interject his own interpretation of what we are seeing and whether it is being performed correctly. He also fills us in on his philosophy about the dubious lasting effects of any revolution and the nothingness of life. The play is a combination of theatrical styles: Brechtian (theater of alienation) and Artaudian (theater of cruelty).

It isn’t important that you be familiar with these vogues, for the theater work you witness is an easy-to-understand caldron of emotions and physical interaction. The director has opted to have all the parts, with the exception of Coulmier’s wife, played by men, including Charlotte Corday (Dana Watkins) and Simone (Jonathan Payne), Marat’s maid. Woven throughout are songs that sound as if written by Brecht’s longtime partner, Kurt Weill. The sound is tinny and the singers, often affecting falsettos, give the musical numbers the air of crazed madrigals. A trio of Polpoch (James Rana), Kokol (Danny Camiel) and Rossignol (David Ryan Smith) are the entertaining songsters.

In a production with such a high level of energy and violence, the acting could easily escalate into overstatement, but McElroen keeps everything under control until the end, when the inmates go berserk. You’ll find it hard not to watch each and every actor to make sure he stays “insane” and you won’t be disappointed by their individual efforts. I guarantee you’ll find yourself trying to avoid a particular stare.

The cast is uniformly excellent, with T. Ryder Smith chilling as de Sade, especially in a revolting moment involving human feces, and Watkins touching as the determined but slightly demented political murderer Corday. This is graphic theater and there are simulated but unmistakable acts of fellatio and anal intercourse. Don’t say you weren’t warned. Kelvyn Bell is the clever musical director and Rajendra Ramoon Maharaj is listed as choreographer, which I assume means crowd control. Denise Hurd gets credit for staging the viscous fights, and Aaron Black’s lighting plan flickers and flashes as a nervous partner to the sound and fury. When the play is over and the final scene is one of litter, dead bodies and pools of water, the audience is left to figure out what to do next. At the performance I attended it took about five minutes for everyone to realize we should get up and get out — something the inmates had been trying to do for almost two hours. 3-4-07

[previous] [next]