Photos by Heather Morris and Ryan Mueller

Excerpts from the reviews

Full reviews are below

“Lear deBessonet’s transFigures takes a multi-layered look at the Jerusalem Syndrome, a subject so ripe for theatricalization that the hit-and-mostly-miss result is a genuine letdown. For those unfamiliar with a condition diagnosed less than 30 years ago, it’s explained in the first speech: ‘Since 1980, Jerusalem’s psychiatrists have encountered a small but increasing number of tourists who, upon arriving in Jerusalem, experience a psychotic episode during which they believe themselves to be a figure from biblical history.’ . . . By this time, deBessonet’s mission is manifest: She wants to poke around religious extremism to see what it suggests about the upside and downside of organized religions . . . St. Joan’s materialization is the most intriguing sequence, since it’s spliced with the interrogation of 1994 abortion clinic killer/hair-dresser John Salvi (Smith) and asks a pertinent question about whose crusading Catholic voices you’re going to believe. At other times, the threading of figures present and past is less illuminating and frequently histrionic. Determined to make her points, deBessonet — aided by choreographer Andrea Haenggi — asks much of her players. More than once they have to manipulate elastic tapes or dance or at least move gracefully while wearing sheets. Sometimes, they have to move the mottled screens as if bearing crosses. They often must convey various stages of what is either spiritual ecstasy or sheer madness, or the fine line between the two. It’s not easy, but the six performers do their level best . . .” David Finkle, theatremania.com

“Like her characters, the young conceptual director Lear deBessonet asks highly interesting questions. It’s her answers that disappoint. In transFigures, an awkward, earnest mix of movement, monologue, found text, dramatic scenes and tableaux, deBessonet tries to walk the perilous line between religious ecstasy and neurotic pathology. The path leads, sadly, to a via dolorosa of deadly experimental didacticism . . . Directors are not playwrights, and when they “conceive” a show—as deBessonet has done by arranging fragments by [various] writers —they run the risk of patchy, bland storytelling . . . The director and her hard-working cast shuffle nobly into the desert of this material, resisting the temptation to score easy ironic laughs but also failing to evoke the fear and excitement that presumably drive fanatics . . . “ David Cote, Time Out NY magazine

“Funny, chilling, enlightening, and mysterious . . . everything an evening at the theatre should be.” The New Yorker

Publicity

Offstage

Above, standing, back, l. to r.: Travis Sawyer, Nate Schenkkan, David Adkins, Dylan Dawson, Benjamin Rollins, Melinda Basaca, Clint Ramos, T. Ryder Smith, Mark Huang. Allison Prouty, Julie Crosby, Joe Gianino.

Front row, l. to r.: Juliana Francis, Megan Carter, Marguerite Stimson, Lear de Bessonet, Sari Kamin, Jenny Sawyers, Alex Finch.

Full reviews

Village Voice, Alexis Soloski – Sick With God. Lear deBessonet dives into religious delirium Many tourists to Jerusalem will place a palm against the Wailing Wall or murmur a prayer in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. But few will separate themselves from friends and family, bathe excessively, make robes from their bedsheets, travel to holy sites, and declaim sermons. These tourists will receive a diagnosis of Jerusalem Syndrome. This rare delirium affects people with little history of psychosis or strong religiosity. Jerusalem Syndrome also affects and informs Lear deBessonet’s transFigures, currently at the Women’s Project, an exhibition of religious mania. In the course of the play we meet two sufferers of Jerusalem Syndrome, as well as Joan of Arc, an undergrad who speaks to God, and John Salvi, the man who opened fire at two Boston abortion clinics. DeBessonet, with the aid of playwright Bathsheba Doran and dramaturg Meg Carter, has assembled her text from such far-flung sources as film documentarian Erin Sax Seymour, religious journalist Russell Shorto, Ibsen, the Bible, playwright Charles Mee, and “Post-It notes of New York secretaries.” But transFigures isn’t nearly so fractured as this diverse list of contributors might suggest (though we’re still not entirely sure about the Ibsen). What cohesion exists owes largely to the fineness of deBessonet’s staging, her ability to mingle multiple scenes, to link them through movement and gesture. DeBessonet’s quite young, a few years shy of 30, but she’s already made her name downtown and wooed impressive collaborators— transFigures includes Juliana Francis as both a devout secretary and Joan of Arc, and T. Ryder Smith as a neurologist and Salvi. DeBessonet is also refining a style—intelligent bricolage, enhanced by murky lighting and shuddering choreography. Though her early productions (Bone Portraits, Death Might Be Your Santa Claus) have been absorbing, one can’t help anticipating her future work, when her various interests and techniques will mature and deepen. TransFigures may concern itself with a fascinating subject, but the piece doesn’t ultimately offer much insight into it. The collage deBessonet has assembled is striking, but perhaps rather shallow. (Tellingly, deBessonet prefers to use the stage’s length rather than its depth.) At 80 minutes, she can’t do much more than introduce the characters and situations. No matter how successfully interwoven, these varied sources and narratives don’t have time to enhance or involve one another. Who knows if the origins of religious mania can ever be successfully demonstrated—onstage or off—but it seems surprising the play would content itself with merely representing them. DeBessonet can offer us every crease and ripple in the bedsheets used to make those robes and togas, but she doesn’t reveal what’s underneath them. 4.27.07

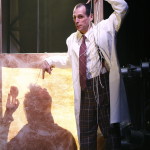

EDGE New York City, Ellen Wernecke – Perhaps it’s the scientist (T. Ryder Smith) in the first act of transFigures, the Women’s Project’s latest performance at the Julia Miles Theatre, who puts it best as he’s dangling from a light rack in a lab coat and plaid pants: “Are religious people brain-damaged,” he asks the audience, “or am I mapping the existence of God?” The beliefs and prejudices of a cross-section of characters are the text of the play, which draws from medieval and modern sources to carry out an intricate (if not particularly well articulated) discussion of religion.

The scientist has been talking about an UC-Santa Cruz student who began playing hooky from a Citibank internship under some kind of religious delusion. He has “Jerusalem syndrome,” a psychological term for people who believe they are a saint or religious figure reincarnated. A bored cop (Nate Schenkkan) discusses them – often naked, hard to dissuade – at a desk overhanging stage left, while eating nuts. It’s not that he doubts the genuine sentiment of a religious experience; he just figures they got the message wrong.

The syndrome is most common in the Holy Land, where a lawyer (David Adkins) and his girlfriend (Marguerite Simpson) are headed on their yearly vacation. The lawyer’s assistant (Juliana Francis) asks him to deliver a letter addressed to “God/Jesus” to the Wailing Wall for her; later, he’ll read that she’s asking for the deliverance of a hairdresser imprisoned for shooting up an abortion clinic in Massachusetts. In a later act, she becomes Joan of Arc, who declares before a tribunal, “I have done nothing but by revelation.”

Director and creator Lear Debessonet uses every square inch of the space to paint these unrelated stories, rearranging pieces to represent subway cars or cubicles. The result is a work that’s more pictorial – from the opening image of dancers draped in white like pilgrims, to a work of devotion in Post-It notes – than primarily textual, despite the wealth of writers and sources drawn on to create transFigures. The images are apt, but occasionally the text leads us awry (as in a bewildering interlude featuring a hilariously over-stylized production of the Ibsen play Lady from the Sea, in which a woman’s lover, represented by a God-like booming voice, tries to convince her to leave her husband). The words become a frame in which these haunting, indecipherable images are set for our wonderment, set off by vivid performances from the talented cast. 4-17-07

Backstage, Nancy Ellen Shore – Conceived and directed by Lear deBessonet, this visually compelling dance-theatre collage mixes linear and nonlinear scenes to explore Jerusalem syndrome, a well-documented psychosis in which tourists experience sudden mystical revelations and wander trancelike in bed-sheet togas through the Holy City as biblical and religious figures. Revolving around a high-powered Manhattan executive and his yoga-practicing wife, this thought-provoking, 90-minute intermissionless work includes text by Bathsheba Doran, Chuck Mee, Erin Sax Seymour, and Russell Shorto, along with excerpts from scientific journals, Joan of Arc’s trial, and Ibsen’s The Lady From the Sea.

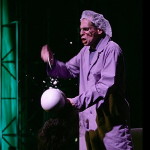

On Jenny Sawyers’ imaginative multilevel set of shifting opaque screens, steel-and-wood platforms, and sheer curtains, deBessonet, who has worked with experimental dance-theatre artist Martha Clarke, incorporates Andrea Haenggi’s expressive modern-dance choreography, Mark Huang’s explosive jazz-fusion sound design, Clint Ramos’ flowing costumes, and Ryan Mueller’s varied lighting to create impressionistic imagery that goes beyond language to bridge the divide between religious revelation and insanity. In one especially powerful Clarke-like image of a young Joan describing her angelic voices, Juliana Francis appears center stage in a stunning blue gown, its long train flowing back into the wings, a symbolic river of undying faith.

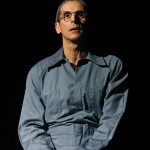

DeBessonet coaxes expert ensemble work from her six-member cast. David Adkins traces a believable arc from cell phone-touting executive through mysticism to mental meltdown, with Marguerite Stimpson progressing from happy tourist to shell-shocked wife. Dylan Dawson is deeply moving as a young man whose transcendent faith is mercilessly squashed. T. Ryder Smith, earlier a coolly-in-control psychiatrist, moves from calm analysis to psychotic rage as a fanatical Catholic hairdresser driven to a murderous abortion-clinic attack — another visually arresting highlight. Nate Schenkkan is pitch-perfect as an atheistic Israeli policeman and a muttering, hunchbacked monk. Francis’ Joan is superb, but she undermines the work’s seriousness by playing a deeply religious secretary with broad Carol Burnett-like physical comedy.

Though its slick, polished veneer is sometimes too cool to invoke deep audience response, transFigures is an impressive effort from a 26-year-old playwright-director experimenting with theatrical forms to shed light on a fundamental aspect of human existence. 4-19-07

nytheatre.com, Kimberly Wadsworth – Jerusalem Syndrome, according to the program notes for Lear deBessonet’s thought-provoking work transFigures, is a rare type of religious mania unique to visitors to Jerusalem or the Holy Land. Those affected may not even come from a deeply religious background, but for some reason, after a couple days touring Jerusalem, they start feeling anxious or agitated, they tell their traveling companions they want to explore the city alone, and may start obsessively taking baths or showers to “purify” themselves—and if left unchecked, they may end up making a robe out of the hotel linens and setting off on a pilgrimage to sites such as the Western Wall or the Dome of the Rock to sing hymns or preach sermons to other befuddled visitors. Within a couple weeks, their zealotry fades and sufferers revert completely back to normal.

In transFigures, DeBessonet uses the syndrome as a springboard for exploring the theme of religious zealotry in general. Using dance and movement as well as dramatization, the play introduces us to a collection of characters—including an upper-class couple visiting Jerusalem on a package tour, a psychologist who theorizes a neurological basis for “out of body” experiences [this is based on a field called neurotheology], a fundamentalist Christian secretary who writes letters of support to an imprisoned abortion clinic bomber, and a young man whose religious fervor is so deep that he spends hours trying to decide which shoe God wants him to put on first. In lesser hands this could have been a huge mess, but deBessonet expertly weaves all the disparate threads together, producing a work that raises questions and inspires contemplation about the nature of faith itself, and the fine line between deep belief and dangerous obsession.

One of the most striking sequences isn’t even about Jerusalem Syndrome. Towards the middle of the play, Juliana Francis takes on the role of Joan of Arc, addressing the audience in a monologue drawn from the actual Joan of Arc’s trial transcripts. Her story is contrasted with that of John Salvi (T. Ryder Smith, in a chilling performance), a pro-life activist who was convicted of two counts of murder in 1994 after a shooting rampage at two Massachusetts abortion clinics. The sequence jumps back and forth between Joan and Salvi’s stories—with dialogue taken from Joan’s actual inquisition, and from a transcript of Salvi’s actual mental competence evaluation. We are drawn into realizing just how much these two had in common—both believed they were being directed by God’s word, both may have committed murder in God’s name, both believed that they were otherwise completely sane, both were nevertheless convicted—which leads to the question of why one of these people is regarded as a monster, and the other as a saint.

All the elements of the production are designed to flow from one sequence to the next—Jenny Sawyers’s set is a series of simple furniture and screens that the cast continually disassembles and reassembles to become everything from an office cubicle to an airline terminal to shields carried by Joan of Arc’s soldiers. Andrea Haenggi’s choreography allows the cast to seamlessly shift from being commuters on a subway to characters in a religious vision. DeBessonet’s staging also puts the cast out into the house at several points, even bringing characters onstage from the back of the theater; it’s easy to be swept away by the play, as it is with a religious experience.

The play raises many questions: Is religious mania a neurological disease? Does a lack of religious fervor and mysticism deprive someone of a certain kind of vitality and passion? Would a benevolent Deity require followers to commit acts that put them in harm’s way? Wisely, though, the play answers none, leaving the audience to—dare I say—meditate upon the answers themselves. 4-13-07

talkin’broadway.com, Matthew Murray – “Are religious people brain-damaged, or am I mapping the existence of God?”In many shows, a statement that potentially incendiary could inspire paroxysms of eye-rolling. Yet it’s not only right at home but even respectful within the textured realm of transFigures. This curious show, which was conceived and directed by Lear deBessonet and has just opened at the Julia Miles Theatre, lassos both science and spirit into a compelling, kaleidoscopic examination of what it means to live in a world that often forces your convictions into predefined patterns.

The chief vehicle for that message here is Jerusalem Syndrome, an actual disorder that leads seemingly sane people visiting the ancient city to develop overwhelming religious predilections that cause them to construct toga-like garments and parade to holy sites to deliver sermons. Yes, it reads like a bad television plot device, and could just as well serve as the launching point for an all-out comedy about what fools we mortals can be.

But she afflicts only one of her characters with it: Bill (David Adkins), an ordinary businessman visiting Jerusalem with his wife Susan (Marguerite Stimpson) who’s unconvinced whether there’s a distinction between God and superstition. So deBessonet sees the illness as a serious symptom of a much greater malady: an uncertain existence. And in suffering from that, Bill is very much not alone – he’s only the most recent victim of a centuries-spanning problem.

Also depicted as part of the ongoing struggle against an ill-defined normalcy are figures as diverse as Joan of Arc, John Salvi (who went on a murderous rampage at an abortion clinic), and a young man named Joshua suffering from a “hyper-religiosity” that slowly begins consuming his life. In one late scene, both Joan (Juliana Francis) and John (T. Ryder Smith) defend against simultaneous inquisitions in a harrowing look between faith and insanity; the cure for Joshua (Dylan Dawson), instigated at the behest of an experimental doctor (Smith again), exists in its own strange state of medical instability.

As the show unfolds, taking in writings from authors as diverse as Bathsheba Doran, Henrik Ibsen, and Chuck Mee, you begin to understand just how blurry the line is between belief in God and belief in science. The final scene, which becomes a broken-down bacchanalia of ropes, Post-It notes, and self-destruction, even suggests there’s no longer any difference between the two: When taken to unnatural extremes, both can lead you to the same dangerous place.

The acting ensemble is generally excellent, though the sad, desperate strength Adkins brings to his would-be prophet makes Bill the show’s most plangently human presence. Of the others, only Francis disappoints, though not as her stately Saint Joan: In her earlier role as a needy, nerdy secretary with a prayer for Bill to convey to God’s Jerusalem P.O. box, her attempted connection to societal disconnection comes dangerously close to overacting.

Excess, in fact, is the greatest weakness of transFigures. While its set or lighting (by Jenny Sawyers and Ryan Mueller) conservatively outline a wealth of realistic and fantastical playing spaces, deBessonet’s staging and especially Andrea Haenggi’s choreography too often mistake busyness for energy. They have no compunction against filling the stage with multiple modern-dance writhe-a-thons, which sometimes convey the characters’ “craziness” but too often detract from the true inner turmoil of people who can’t understand why everyone doesn’t see the world as they do.

However, seen as yet another reflection of the show’s primary theme, stated by one character as “the relationship between art and atrocity,” it’s never much more than temporarily distracting. And in the finale, when most of the cast revels about the stage – some in pain, some in joy, but all at last individuals – there’s real beauty in their feeling. Another one of the show’s questions asks, “Did God create the brain, or did the brain create God?”, but this scene – and most of transFigures – affectingly demonstrates they’re more or less the same thing.

theatremania.com, David Finkle – Lear deBessonet’s transFigures takes a multi-layered look at the Jerusalem Syndrome, a subject so ripe for theatricalization that the hit-and-mostly-miss result is a genuine letdown. For those unfamiliar with a condition diagnosed less than 30 years ago, it’s explained in the first speech: “Since 1980, Jerusalem’s psychiatrists have encountered a small but increasing number of tourists who, upon arriving in Jerusalem, experience a psychotic episode during which they believe themselves to be a figure from biblical history.”

That description goes some way toward clearing up the prologue, wherein the cast of six actors, wrapping themselves in sheets, writhe on the floor or push against a side wall or other parts of Jenny Sawyer’s set with its tall, opaque screens. It appears that demons — maybe Mary Magdalene and Moses — are taking possession of the ensemble. “Oh, you’ve got another John the Baptist,” notes Victor (Nate Schenkkan), the policeman assigned to the Jerusalem Syndrome unit, just seconds later. Once Victor has declared himself, deBessonet brings on five other contemporary figures. There’s Gene (T. Ryder Smith), a scientist studying a young man named Joshua (Dylan Dawson), who regularly talks to God and whose brain patterns during these spells is of interest; Bill (a persuasive David Adkins) and Susan (Marguerite Stimpson), a married couple about to spend time in Israel; and Bill’s colleague Margaret (Juliana Francis), who spends her downtime writing slogans on Post-its that she freely distributes and who also collects 61 prayers from other employees for Bill to insert in the Wailing Wall. By this time, deBessonet’s mission is manifest: She wants to poke around religious extremism to see what it suggests about the upside and downside of organized religions. And although she’s billed as having conceived the play-cum-movement piece, the text is supplied, according to the script, by Bathsheba Doran, Russell Shorto, Erin Sax Seymour, Charles Mee, Henrik Ibsen, Joan of Arc, the Bible, and Post-it notes of New York secretaries. That’s some collection of motleys! A slice of Ibsen’s Lady From the Sea is rendered melodramatically, apparently because that play’s protagonist, Ellida, is an example of increasingly obsessive behavior; and Joan of Arc shows up because she heard voices. (Both roles are played by Francis.) Indeed, St. Joan’s materialization is the most intriguing sequence, since it’s spliced with the interrogation of 1994 abortion clinic killer/hair-dresser John Salvi (Smith) and asks a pertinent question about whose crusading Catholic voices you’re going to believe. At other times, the threading of figures present and past is less illuminating and frequently histrionic. Eventually, one of the focal characters shows alarming signs of the seven stages of Type III Jerusalem Syndrome — among them, taking many showers, rigging a toga from hotel bed linens, and delivering an incoherent sermon within sermonizing distance of a landmark. The temporarily deranged person’s identity won’t be divulged, but the one most likely to rip the sheet from the mattress is obvious from the get-go. Determined to make her points, deBessonet — aided by choreographer Andrea Haenggi — asks much of her players. More than once they have to manipulate elastic tapes or dance or at least move gracefully while wearing sheets. Sometimes, they have to move the mottled screens as if bearing crosses. They often must convey various stages of what is either spiritual ecstasy or sheer madness, or the fine line between the two. It’s not easy, but the six performers do their level best. During the initial voice-over, this startling statement is made: “Over the last 20 years, over 1200 people have been diagnosed with what has come to be known as Jerusalem Syndrome. Of all the patients hospitalized, 66 percent were Jews, 33 percent were Christians, and one percent had no known religious affiliation. Well, whaddya know? Jews are twice as likely to believe that they’re Abraham sparing Isaac than Christians are likely to perambulate as the disciple Paul. Although deBessonet hopes TransFigures will spur reexamination of one’s faith and its origins, the play’s real bonus may be as a guide to finalizing one’s Middle East travel plans.

That Sounds Cool, Aaron Riccio – Lear deBessonet’s transFigures isn’t just a passionate play, it’s a play about passion, from the psychological Jerusalem Syndrome to the allegorical Ibsen, to plain human behavior. Excellent production values triumph in this remarkable tapestry of ideas, and this should be on everyone’s list for April.

transFigures fades in with a series of bodies, their genders indecipherable at first beneath their white robes, lying in front of two metal towers and three paper-thin Chinese walls. As music filters through the theater, a purposeful type of ambient electronica, the bodies come alive with an inexplicable passion: they move, they shudder, they roll across one another, they live. When it is over, they rest again, just as inexplicably, on the stage as the lights come down. Rest easy, dear reader, this is just the curtain-raiser for another stunning theatrical work by Lear deBessonet (see Bone Portraits), a prologue to a seamless collage of texts and ideas revolving around (but in no way limited to) the exploration of Jerusalem Syndrome.

The center of the play follows Bill (David Adkins) and Susan (Marguerite Stimpson) from their New York office (complete with a God-crazy secretary played with unnerving accuracy by Juliana Francis) to Jerusalem. At the same time, two subplots (lacing exquisitely in and out of this main story) focus on neuroscientist Gene’s study of Joshua, a young boy who is afflicted with hyperreligiosity and a series of theatrically thrilling delusions, as well as on an Israeli therapist’s engaging explanation of the syndrome. (A psychosis of passion overcomes the afflicted, and results in them delivering a confused sermon in a holy place.)

Rather than narrowing the focus after establishing the necessary technical background, deBessonet widens the scope, abetted by her textual patchwork: the show is written primarily by Bathsheba Doran, but involves text from Chuck Mee, Erin Sax Seymour, and Russell Shorto, to name a few. If she is trying to deliberately trick our brain’s OAA (Orientation Association Area), to make us forget, as with Jerusalem Syndrome, where we are: she succeeds. Mark Huang’s ambient sound design sets the mood, Andrea Haenggi’s choreography breaks down the delusion (shambled, joyous, confused, and satisfied masses), Jenny Sawyer’s multileveled set (reaching along the sides into the audience and up steel towers to the sky) breaks into multiple dimensions, Ryan Mueller’s lighting (or darknessing) evokes the phantasmal, surreal, and modern with a profoundly succinct grace, and we? We are transported.

We are also astonished by the range and fluidity of deBessonet’s direction. With the slightest sweeps of lighting and the rare use of props (always malleable items, like string, or paper), she is able to evoke not just the awe-inspiring, but the awful, and often at the same time. Those paper-thin walls are just as easily wailing walls, being spun around the theater by the cast, as they are the Wailing Wall. At the same time, she can bounce from idea to idea, without ever seeming fragmented, which is largely a credit to her malleable cast. For instance, her summarized spoof of Henrik Ibsen’s Young Girl and the Sea is one of the most shamelessly embarrassing feats of ham on the stage, and it flows just a few minutes later into a cross-section between testimony of the abortionist-killing hairdresser, John Salvi (T. Ryder Smith is flawless here) and everyone’s favorite God-hearing martyr, Joan of Arc. Although the texts are very different in tone, once deBessonet weaves something into her tapestry, you can’t imagine ever hearing them apart again. It’s just one more wonderfully indelible effect of the play.

It had better NOT be snowing in Bakersfield: if transFigures is what its like to lose one’s mind, or to be touched by God, then we should all be so lucky, for this is a beautiful, beautiful play. 4-16-07

Obscene Jester blog, Tweed – What Hath God Wrought? TransFigures, the most recent production of Stillpoint Productions, would have stood on its own at any moment in recent political memory. But the fact that it happens to be playing at a particular flashpoint brings it an even greater resonance that makes it a must see amongst a sea of theatrical drek right now.

The piece is a rumination on Jerusalem Syndrome, a psychological condition affecting people who visit Jerusalem which catalyzes a week-long psychotic break during which these people believe themselves to be biblical figures. They tour the city with hotel sheets wrapped round them like togas and preach the Word of God. T. Ryder Smith, who plays an Australian psychologist asks us: “Are religious people brain damaged?”

The next 75 minutes are a tour de force of directorial, acting, and writing might. Director Lear deBessonet, whose work I have always admired has really brought her aesthetic forward in transFigures. Her penchant for pastiche (which in this one includes a Chuck Mee, Joan of Arc, and an amazing Ibsen interlude), examining her subject fully and with an overwhelming amount of compassion and humanity, has its greatest success in its evenhanded-ness. The religious zealots are pointedly human, looking for their purpose like anyone else, and the atheistic cosmopolitan couple are much easier to identify with, but still often ooze with condescension.

Add to that an incredible ensemble of actors and transFigures is a lovely theatrical event. But with recent events such as the upholding of the partial-birth abortion ban, the religious strife resulting in a horrific body count in Iraq, the end of the ceasefire between Israel and Hamas, and of course Cho Seung-Hui claiming to be a martyr like Jesus before taking it out at Virginia Tech, the religious fervor of the moment must be examined.

Science versus faith is by far not a new concept, but we seem to have reached a moment where it has reached some sort of rhetorical boiling point, and not in a good way. Most of the work done on the subject is a sophomoric spitting contest among politicians, religious leaders, and media leaders, where artificial positioning and dramatics are prized over logic, and, most importantly, no one is willing to listen to another.

If only there could be more forums like transFigures to help us get through. 4.25.07

[previous] [next]