Photos by Frank Aymami, Skip Bolen, Paul Chan, An Heisenfelt, and Donn Young.

Excerpts from the reviews

Full reviews are below

“The most accessible, the funniest, the most moving and meaningful “Godot” we are ever likely to see. . . . This is stimulating, adventurous, theater of the first order . . .” David Cuthbert, New Orleans Times-Picayune

“Ultimately, it was the audience–residents of the surrounding neighborhoods, people from across a city whose every block was marked by the storm–that night after night made this performance great because of their special sensitivity to “tragicomedy,” the designation Beckett gave the play. . . .” Billy Sothern, The Nation magazine

“Great art experiences are often about opening up and connecting with something outside of yourself or synthesizing your own experiences with someone else’s vision. And that’s eventually what happened for me . . . In the distance, the “set” was framed by Claiborne Ave bridge on the left and the Florida Avenue bridge to the right, a dark stretch of newly constructed levee between them, holding back the unseen Industrial Canal, a loaded symbol of so much even before the storm, of economic promise and the civic neglect it created. Bottom-lit, expressionistic oak trees fronted of the levee. Electrical towers along the canal towards Lake Pontchartrain flashed intermittent warnings. Ninth Ward resident Robert Green Sr.’s FEMA trailer far to the left and a blighted abandoned cottage off to the right. The road, N. Prieur, appears out of the darkness, fields of weeds on either side, the ragged dashes of the lane divider hinting at its former existence as an urban street. The setting is testament to how quickly and thoroughly nature reclaims its own here in the subtropics, to the beautiful and sad tenuousness of civilization. That was just the background. The immediate “stage” where most of the action occurred had its own stirring composition. Left to right: an upright utility pole, a north-leaning storm-bent pole, an upright artificial stage “tree” in the center of the road as a sort of visual fulcrum and to the right another north-leaning signless post, and a rusty fire hydrant, used for full comedic effect. The soundscape was just as integral: distant police sirens, tugboat and train horns the some sharply wailing birds, all pulsing quietly in the background, muted by the once treacherous canal and surrounding empty lots of former homes. It was all so well executed . . . that Beckett’s characters seem to emerge from this landscape, to have always been there. . . .” Anne Giselson, NOLAFugees blog

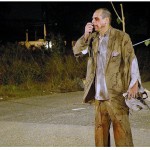

Rehearsals – Neighborhoods

9th Ward

This was our primary performance space, the neighborhood right next to where the levees broke, which received the worst of the flooding. There were only a handful of houses still standing, amid the acres of grassy lots which used to be houses and yards.

Photos by the Hinge Collective

Top photo by Chris McElroen

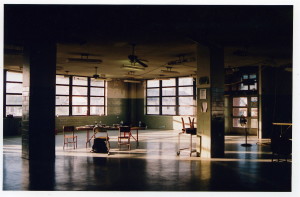

St. Mary’s School

St. Mary’s public school was the tallest building – 3 stories – in the 9th Ward, whose rooftop became an island in the floodwaters. When the waters receded, the upper floor became a sanctuary, and when the ground floor was once again drained, a rescue center and shelter. The school was closed for use when we were there, but the city allowed us to rehearse in the old cafeteria. You could see the high-water marks still on the upstairs walls, and messages written on the blackboards.

Photos by the Hinge Collective.

Gentilly

The Gentilly neighborhood was our second performance space, and where actor Wendell Pierce had grown up, and still had family. The houses there were undergoing renovation during our time in NOLA. Many, including our performance house, had been gutted, rubble mixed with personal belongings littering the grounds.

Photos by the Hinge Collective

Top photo by Chris McElroen

Rehearsals

Offstage

The team

Curtain call, opening night

Curtain call, closing night

Above: helping out with some neighborhood clean-up

Full reviews

New Orleans Times-Picayune, David Cuthbert – Godot is great. Samuel Beckett’s classic ‘Waiting for Godot’ arrives on a street corner in the blighted Lower 9th Ward to overflow crowds, and demonstrates just how powerful and relevant theater can be in post-K New Orleans. It was a famous photographer, Henry Cartier-Bresson, who said that the more specific a thing is, the more universal it becomes. With its performance on a blighted Lower 9th Ward intersection, Samuel Beckett’s “Waiting for Godot” becomes very much a New Orleans “Godot,” and its specificity is not a contrivance. On the contrary, it illuminates the play. Christopher McElroen’s staging is the most accessible, the funniest, the most moving and meaningful “Godot” we are ever likely to see. It is ours, it speaks directly to us, in lines and situations that have always been there, but which now take on a new resonance. McElroen and company accomplish this, for the most part, naturally, with attitude, line delivery and yes, a few interpolations not in the text. (The Satchmo imitation may be a bit much, but the audience loved it.) This is theater N’Awlins style, with pre-show gumbo, a brass band second-lining us to our seats and an audience as eclectic as the city itself. It is a simple yet magnificent gift from artist Paul Chan, who provided the concept in concert with McElroen’s original Classical Theatre of Harlem post-Katrina staging. It was paid for (to the tune of $200,000) by Creative Time, the New York-based arts presenters. To that group, let us add the wondrous cast, led by native son Wendell Pierce, who was determined that the “Godot” he played in New York should come “home,” and to which he has contributed a characterization of such earthy variety, vigor, hilarity and passion that as his performance unfolds, so does his status as a great actor. The time has long since passed when “Godot” was regarded as “a mystery wrapped in an enigma,” as Brooks Atkinson famously described it in his 1956 New York Times review of its Broadway debut. This is Beckett’s merciless, tragi-comic view of mankind, playing at life to avoid the specter of death, awaiting an enlightenment that stubbornly refuses to appear. But man, being what he is, will pin his hopes to something as ephemeral as two leaves sprouting from an otherwise barren tree. If that’s not us, I don’t know what is. “Nothing is as funny as unhappiness,” according to Beckett, and given that standard, “Godot” is a laugh riot. Vladimir and Estragon (Didi and Gogo), two of the downtrodden dispossessed, meet at the corner of North Prieur and Reynes streets, as they probably did yesterday and most likely will tomorrow. There are fields of weeds where houses once stood. Estragon always arrives after having been beaten for no reason he can discern, but which we can. When Pozzo approaches from afar with lights and siren, Didi and Gogo “assume the position,” kneeling down with their hands crossed in back of their heads.”We are waiting for GAH-DEAUX,” Didi keeps reminding Gogo, whose memory is hazy, one day flowing into another (sound familiar?). They are alternately depressed to the point of suicide or passing the time with verbal pingpong games of the “Who’s on first?” variety, indulging in low comedy shtick (pratfalls, kicks in the shins, groin and olfactory distress) and endless vaudevillian hat tricks. No one just places his bowler on his head. It takes several W.C. Fields spins to get it there. Enter the affluent Pozzo, in elitist white. Riding an adult tricycle he has a long, trailing rope attached to Lucky, his elderly human pack mule, who pushes a shopping cart full of bulging plastic bags and an ice chest. “The road seems long when one journeys all alone for six hours on end and never a soul in sight,” says Pozzo. Lucky doesn’t count, of course. Lucky is a human abstraction, there only to serve Pozzo’s needs and whims, although Pozzo deigns, in condescending fashion, to regard Gogo and Didi as “human beings — as far as one can see.” Lucky does what Pozzo commands and when distraction is needed, Lucky dances and then “thinks,” in a rambling monologue of seeming gibberish in which nuggets of philosophy whizz by. Pozzo, megaphone in hand, turns Southern politician on the stump, but can’t quite remember what the rabble want him to tell them. Disgusted by his cruelty toward Lucky (“To treat a man like that!”), master and slave take their leave after comically protracted goodbyes. (I half-expected to hear Judy Holliday’s “Adieu to ya.”) A boy appears out of the audience to tell them that Godot cannot come today, “but surely tomorrow.” The second act begins in lively fashion with Pierce strutting down the road, giving out with a Mardi Gras Indian chant, a bit of “Hey Pocky Way” and a Beckett lyric set to a New Orleans street beat. Gogo has been beaten again and the two men try to find “something that gives us the impression that we exist.” But everything has changed in a single night. Comedy is momentarily halted by the chill of fearful thoughts and images they have been trying to keep at bay — hell, death, corpses (“You don’t have to look.”/”You can’t help looking, try as one may”), the whispery sounds of the dead talking. Pozzo returns, bloodied and apparently blinded and calls for help as he and the now completely mute Lucky collapse. “Let us do something, while we have the chance!” Vladimir cries, not only to Estragon, but to the audience. “To all mankind, they were addressed, these cries for help still ringing in our ears! But at this place this moment in time, all mankind is us, whether we like it or not!” Didi and Gogo help Pozzo to stand. “Where will you go from here? Vladimir asks. “On,” says Pozzo. “What do you do when you fall far from help? Vladimir asks. “We wait till we can get up,” Pozzo says. “And then we go on. On!” As Gogo sleeps, another Boy comes, with the self-same message from Godot. At the end, Vladimir and Estragon agree to go. But as the light fades to black, they do not move.The surprise is how easily the play adapts to what we have experienced over the last two years and the clarity it brings to what some people still find a problematic text. There is no great entity riding to our rescue to “fix” what has been broken. We must do it ourselves, as we have, with the help of compassionate strangers and our own crazy courage.The play brings light, life and humanity to a dark corner of the city and the ongoing dark night of our souls. This is stimulating, adventurous, theater of the first order in which we see ourselves in the mirror of a great play. While the director attends meticulously to the details of character and intricate comic business, he also makes great use of the broad canvas at hand, in spatial relations, stumbling forays into the weeds and the dramatic entrance and exit that two trees in the distance on North Prieur Street provide. The lighting and sound are excellent, given the circumstances, and as a bonus, tugboats from the Industrial Canal provide haunting echoes. Pierce, who swings between funkily antic and broodingly morose, becomes a figure of moral stature by play’s end, roaring his anger into the void as he clings to the small green leaf of hope. J Kyle Manzay’s entertainingly complaining Estragon has the most cosmic line, “Do you think God sees me?” plangently delivered. He is the loopy Laurel to Pierce’s Hardy, and is as dexterous verbally as he is physically. The easy rapport between the two men, their camaraderie, the irritating essential each is to the other, is brilliantly realized.Tall, thin and angular T. Ryder Smith’s Pozzo is the oppressive “have” to the have-nots; the self-satisfied exploiter, user and abuser. To this, Smith adds notes of dizzy, addled eccentricity, throwing himself into Pozzo’s blind bumbling in the bulrushes like a man who is rag doll drunk. McLaughlin is the very essence of Lucky, the aging, “servant” Pozzo arbitrarily punishes, insults and orders about. McLaughlin stands there stoically, laden down with suitcases, the burdens of the human race. He will dance foolishly but purposefully as a man caught in a net — his life story — and pontificate when his hat is placed on his head, as if all knowledge resided there. He is every soul plodding through life at the caprice and cruelty of others. Completing the cast are Tony Felix and Michael Pepp as The Boys, played as polite Catholic school kids and handling their lines with disarming aplomb. The shadows of silent movie comedians have always hovered over “Godot” and after bows had been taken opening night, the six players turned around in unison and walked down the road, like Charlie Chaplin’s Little Tramp. They also walked into New Orleans theater history. 11/6/07

Elosticity blog – The production of Waiting for Godot in New Orleans performed last weekend (November 9 and 10) among the ruins of that great city was one of the most perfectly realized works of art I have ever experienced. The city, and, more specifically, the front porch and gutted interior of one of a row of ruined houses near the London Street Canal breach, is as appropriate a stage set as Sarajevo was for a Susan Sontag production during the war in Bosnia. The audience followed a Second Line brass band towards the bleacher seats along Pratt Street that served as a theater. The brass band of course always leads celebrations and funerals. The local band was the perfect introduction to the dark, wrenching dialog that wears a veneer of vaudvillian mirth. The production itself straddled the two tendencies between celebration and mourning. Everyone ‘got’ the discarded roadside fridge that Estragon opens to look for a carrot; later, as Vladimir rails against being abandoned and forgotten, it sounded like he could only be talking to and about New Orleans. The fact that Vladimir was played by the incredible Wendell Pierce, a New Orleans native, only deepened the connections between the play and the city. 11/13/07

The Nation magazine, Billy Sothern – But isn’t this play rather pessimistic, I’ve been asked. Meaning, wasn’t it depressing for an audience in Sarajevo; meaning, wasn’t it pretentious or insensitive to stage Godot there?… The condescending, philistine question makes me realize that those who ask it don’t understand at all what it’s like in Sarajevo now, any more than they really care about literature and theatre. –Susan Sontag, “Waiting for Godot in Sarajevo.” Signs on corrugated plastic–A Country Road/A Tree/Evening–had been fixed to wooden telephone polls all over town with roofing nails and zip ties. Who knew what the hell they meant, or even noticed them next to the Clarkson for City Council, Roof Repair and other political and commercial signs that litter our neutral grounds and cityscape in postdiluvial New Orleans? But as it turns out, those first signs, looking every bit as much the disposable junk as the others, were genuine contemporary art, made by Paul Chan, a New York art star. They gave notice to the city, however obliquely, using the opening stage directions of the play–Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot–that he was to stage on two consecutive weekends in two of the most devastated neighborhoods in America. The ambiguity of the signs did not inhibit a packed house for each of the five nights the play was performed for free in New Orleans. Indeed, it was only planned for four nights–two in the Lower Ninth Ward and two in Gentilly. But Chan, the Classical Theater of Harlem–which staged the play here and in New York–and Creative Time, a New York nonprofit dedicated to public art, which produced and funded the visionary endeavor, added a fifth night after turning back hundreds of people from the performances in the abandoned Lower Ninth Ward. After the lucky few hundred folks who made it in the first night ate gumbo and were then drawn to bleachers a couple of blocks away by a brass band and dancers from The Big Nine Social Aid and Pleasure Club, a de rigueur homage to the city’s vernacular culture, people took their seats. The stage, an abandoned intersection, was in the midst of several wasted city blocks where aggressive local flora had begun reclaiming the neighborhood as a backswamp, now that bulldozers had cleared most of the homes destroyed following Hurricane Katrina. The play was framed in the distance, like the curtain at the back of a stage, against a newly built concrete flood wall, whose earlier incarnations–in 2005 during Katrina and in 1965 during Hurricane Betsy–had failed to keep the water at bay. The Rev. Charles Duplessis introduced the premiere and invoked the lost lives specific to this “charming spot” on “this bitch of an earth,” as Beckett’s characters later said. “Where you are sitting is where someone’s home was…. People lost their lives right in this area,” Duplessis explained with great solemnity, clearing the air momentarily of the joyful music that still rang in our ears. And then the familiar, repetitive, morally ambiguous play began. Two tramps, Vladimir and Estragon, talking, waiting for Godot, trying to pass the time, despairing. Pozzo and Lucky appearing, then disappearing. The boy coming to tell the tramps that Godot would not be coming today, “but surely tomorrow.” Roughly the same thing occurring in the second act. The play is dark, written after the world spiraled into uncontrolled horror and barbarity by an Irishman who saw it up close. But it is also a comedy in the modern sense–funny like slapstick. Wendell Pierce, a Gentilly native and TV star from HBO’s The Wire, played Vladimir, admirably emphasizing the vaudevillian elements of the play and riffing on Louis Armstrong, another native son, and “Li’l Liza Jane,” an important song in the New Orleans jazz repertory. T. Ryder Smith was arresting as brutal Pozzo. Everything else, from the other actors to dynamic staging to the bare sets in the morally charged landscapes, worked well. But ultimately, it was the audience–residents of the surrounding neighborhoods, people from across a city whose every block was marked by the storm–that night after night made this performance great because of their special sensitivity to “tragicomedy,” the designation Beckett gave the play. While certainly not only in New Orleans, it is clear that especially in New Orleans we are able to understand and embrace life’s absurdity, how we all wait for good or bad, how terribly uncertain our futures are, but then we are immediately able to belly-laugh at Estragon’s stinking feet or Pozzo’s sudden blindness or, worst of all, the tramps’ horror at having to wait another day and their contemplation of suicide while Estragon’s pants sit at his ankles. The audiences in the Lower Ninth Ward and Gentilly, like the audience in Sarajevo during the siege of that city, or the audience at San Quentin prison, where this play was staged in 1957, or most any other audience, I expect, did not laugh at these misfortunes with any derision or condescension but with empathy. Here in New Orleans, though, our identification with the humor in the play was slightly sharper, arising not just from the storm and its bitter aftermath but from more than a century of local culture built around the proposition that you need to laugh, sing, eat–find joy wherever you can–to keep from crying. And like the characters of the play, we are too aware of our folly. We ask ourselves why we do the things we do. Primarily, why do we live here? Our friends and neighbors were left to die in the storm’s rising water. Now they are being murdered at alarming rates in our streets. Even now, more than two years after the storm, many more things are worse than are better. And given the lack of political vision in the present, the horrors of the past–the flood, the despair, the poverty–will no doubt persist or repeat themselves. But unlike any other city in America, those of us who are here now have chosen to be here. We were forced to leave, and we returned. And we stand at a barren crossroads, beside dark oaks and magnolias, at the twilight of the life of our city, and we rebuild our shotgun homes, our double galleries and our slab tract houses in Gentilly, New Orleans East, Central City, Lakeview and the Lower Ninth Ward. We wait for leadership and genuine assistance to keep us from flooding again, to give meaning to the promises that we relied upon. But we no longer expect it to come, and we know that our work may all come undone. It likely will. But, like Vladimir and Estragon, we will keep coming back. Because this is what we do. This is who we are. 12/3/07 (12/31 issue)

NOLAFugees blog, Anne Giselson – That Tree, That Levee. I started noticing the signs in mid-October, on telephone poles across the Seventh, Eighth and Ninth Wards. Down Claiborne Avenue, St. Claude Avenue, by the Lafitte housing projects, in front of the Saturn Bar, the Sound Café, across from the bus stop at Dauphine and Royal. Black lettering on white: A country road. A tree. Evening. Beckett’s spare opening lines to Waiting for Godot. The plastic corrugated signs niftily appropriated the visual vernacular of post-K New Orleans, those ads that overran neutral grounds, sprouted from poles and trees soon after the storm as more sophisticated communication broke down– advertising gutting services, contractors, what schools and businesses were opening, who was hiring, or running for what office during our seemingly interminable election cycles. The signs were connected to upcoming productions of Beckett’s seminal play by New York-based Creative Time, a public art presenting organization and once I noticed them, I couldn’t unnotice them. They were reminders of the 1000 plus pages of Beckett I tried to read during grad school that settled unsettlingly somewhere in my brainpan. Godot seemed an interesting choice to make some sort of statement about New Orleans; it was created in a post-war landscape, purportedly influenced by Beckett’s experience in the French Resistance, underground, under siege, waiting for messages, for signs, shadowy encounters in which enormous things were at stake, passing the time under duress with humor and rumination. Quietly fighting the good fight. The signs were getting me generally hyped about the Lower Ninth Ward production of the play near the newly rebuilt levee. Then I started asking people what they thought of the Godot signs. The reactions ranged from thoughtful bafflement to outright dismissal. No one I talked to connected them to the play, so the signs weren’t quite marketing. The quote was enigmatic, innocuous, lacking the provocative spirit of most street art– a missed opportunity in my eyes, since they were going to all the trouble of breaking the law by affixing them to public property. As it turns out, artistic director Paul Chan placed them there to illustrate that the play could’ve been performed on any street in New Orleans, a gesture in line with the expansive and generous nature with which he approached the project, working hard with members of the community to make sure it was executed as sensitively as possible. But after hearing so many I don’t get its, the signs began to give off a whiff of “those who know, know” while keeping the guys hanging out at the Wing Shack on N. Claiborne at arms length. But I was still very psyched about the production. We’d heard that scores of would-be playgoers had been turned away for Friday night’s premier, so we arrived an hour early, as did about a hundred others. The sky darkened. The crowds grew. The program promised a “Gumbo Reception” followed by a “Second Line—Follow the Band to the Play.” One reviewer said the fake second line and gumbo made it feel like a real “Nawlins’” production. What felt most “Nawlins” to me was that while hundreds of us stood around in line for a ticket, some for over an hour, joking around, grumbling, spraying ourselves with the free mosquito repellent, VIPS with lanyards sailed past us, as did some neighborhood residents who tried to argue that they’d lived there their whole lives and they shouldn’t have to wait. After getting the ticket and being admitted to the staging area a block down from where the actual play would be performed, I had a moment’s sense of unease while in line for the port-a-let across from a grafitti-riddled storm-trashed house. Down one side of the road were hundreds of people in a soup line and on the other side was a mob crowding some police barricades, waiting. There was speculation that this was a shrewdly engineered part of the pre-play experience. By the time many folks got to their seats, it would have been about a two-hour wait. While I know the free “gumbo party” and perfunctory brass band were meant to be gestures of generosity, tributes to our unique culture, etc. For me, they also came off as patronizing, or pandering and wholly unnecessary. Is this what New York thinks we do down here every time more than ten of us get together? We know that’s what L.A. thinks. Or, it could’ve been the brain-child of a well-meaning local. It may seem like the apex of cynicism to bitch about free gumbo and paid musicians, but joyless artificial second-lining makes even natives feel like awkward conventioneers. With all this post-Katrina cultural boosterism, I feel as though we’re in danger of self-parody and provincialism, always pointing our fingers back at our own ”uniqueness” but always the same uniquenesses, which become more and more commodified, less and less attached to their origins and ultimately threatening the true cultural strength of the city. But I heard John Folse’s gumbo was pretty good. Great art experiences are often about opening up and connecting with something outside of yourself or synthesizing your own experiences with someone else’s vision. And that’s eventually what happened for me when we finally made it to our seats. The Lower Ninth Ward setting at the intersection of Reynes and N. Prieur was so full of drama and pathos it would’ve been a full night of theater to just sit in the folding chairs on the risers and look at the landscape. The performers were truly, as billed, world class, of course there was Beckett, gazing into the void and filling it with vaudeville, friendship, meager hope, questions, venereal disease, abuse, poetry and despair. Among other things. If your brain got temporarily shorted out by the elliptical dialogue or you couldn’t actually see the actors because of your bad seats, it didn’t necessarily lessen the experience. In the distance, the “set” was framed by Claiborne Ave bridge on the left and the Florida Avenue bridge to the right, a dark stretch of newly constructed levee between them, holding back the unseen Industrial Canal, a loaded symbol of so much even before the storm, of economic promise and the civic neglect it created. Bottom-lit, expressionistic oak trees fronted of the levee. Electrical towers along the canal towards Lake Pontchartrain flashed intermittent warnings. Ninth Ward resident Robert Green Sr.’s FEMA trailer far to the left and a blighted abandoned cottage off to the right. The road, N. Prieur, appears out of the darkness, fields of weeds on either side, the ragged dashes of the lane divider hinting at its former existence as an urban street. The setting is testament to how quickly and thoroughly nature reclaims its own here in the subtropics, to the beautiful and sad tenuousness of civilization. That was just the background. The immediate “stage” where most of the action occurred had its own stirring composition. Left to right: an upright utility pole, a north-leaning storm-bent pole, an upright artificial stage “tree” in the center of the road as a sort of visual fulcrum and to the right another north-leaning signless post, and a rusty fire hydrant, used for full comedic effect. The soundscape was just as integral: distant police sirens, tugboat and train horns the some sharply wailing birds, all pulsing quietly in the background, muted by the once treacherous canal and surrounding empty lots of former homes. It was all so well executed by Classical Theater of Harlem director Christopher McElroen that Beckett’s characters seem to emerge from this landscape, to have always been there. Gentilly native Wendell Pierce played Vladimir, J. Kyle Manzay as Estragon, T. Ryder Smith as Pozzo and the local theater veteran Mark MacLaughlin as Lucky. Interestingly, or maybe not at all, each of the principals, save MacLaughlin have appeared in Law & Order episodes. Yes, woven throughout Beckett’s story of two men waiting by a road for the elusive Godot who never shows, there were the crowd-pleasing local references, Mardi Gras Indian chants and even an Armstrong imitation by Pierce. One of the more obvious script changes occurred when Vladimir and Estragon argue about whether or not they’re in the right place, Vladimir queries about ”That tree… that levee.” Beckett’s original line had Vladimir referring to “that bog” with stage directions for him to point out into the audience, presumably the morass that is humanity. This tiny change shifts attention away from the audience to the levee, our ubiquitous symbol of failure. The set never lets you forget either– whenever Estragon sat exhaustedly at the base of that north leaning pole, that stuck storm compass, my heart nearly broke. Vladimir and Estragon are played as amiable neighborhood guys, by turns easy and joking, peevish or anguished. Pozzo is clearly “The Man” in his ruined Tom Wolfe get-up and megaphone, his swaggering but addled authority inextricably bound to Lucky, the object of his abuse and derision. Talk about a metaphor for living in New Orleans. He arrives on the scene on his three-wheeled bicycle, Lucky tethered to a shopping cart bulging with plastic bags and miscellaneous street garbage. Surveying the situation, the decimated landscape and its weathered residents, Pozzo whips out a disposable camera and aims it at the abandoned house at the edge of the weed patch, a nod to the crass voyeurism the disaster scene sometimes invokes. His line “It’s a disgrace” is followed by the grating, amplified winding of the camera and then a hollow click. “But there you are,” he concludes. One of the most moving moments was in the second act when Vladimir runs off through the man-high weeds to a small platform, shouting out the lines that express the core of nearly all of Beckett’s work. “Astride of a grave, a difficult birth. Down in the hole, lingeringly, the gravedigger puts on the forceps… the air is full of our cries!” Vladimir’s voice echoing beyond the audience across the empty foundations and sparse progress of Lower Ninth Ward and down towards the trailers and packed bars of St. Bernard Parish. When Pozzo and Lucky return later in the play, in tatters, Pozzo, blinded and bloodied, crawling along the ground, the scene takes on the intricate despair of a Brueghel painting. Everyone gets dragged down in the end and yet people carry on despite it, because, for the most part, that’s what human beings do. The play ends, famously, with the final exchange: Vladimir: Well? Shall we go? Estragon: Yes, let’s go. They do not move. Theater being both a communal and individual experience there was a variety of reactions among the audience. Some thought it too long or too uncomfortable and left at intermission, some didn’t get it at all, some, maybe most, (myself included) deemed it just extraordinary, and one, my husband and first time Beckett-goer thought it should’ve been six hours long. There was some griping about too many New Yorkers at the Friday night show, too many white people at the Saturday night show, too much money being lavished on an out-of-state production, not enough of the lower Ninth Ward community in attendance. But even if it were just for the few, for Mr. Green whose trailer served as the dressing room and a distance set element, who lost his granddaughter and mother to the storm near that very spot, then I imagine it was worth it. I think the Godot production succeeded grandly on many levels– it brought some national and local awareness, engaged some locals and neighborhoods in way that reaffirmed the magnitude of their experience and reassured them that they weren’t completely forgotten. Plus, something was really happening down there. A writer friend who lives in Holy Cross said that the most exciting part of the event for him was seeing hundreds of people hunting for parking in the Lower Ninth Ward. And it’s true that all the activity was heartening, the presence of a sense of purpose, of resources being expended (though later carted away) and care. All in all it’s what vision, talent, money and can accomplish. There’s already been a whole lot written about the connection of the play to the city’s current state of affairs, emphasizing the idea of New Orleanians “waiting.” Waiting for FEMA, waiting for Road Home money, waiting for neighbors, waiting for a master plan, etc. This, I imagine unintentionally, emphasizes a certain passivity to the reconstruction that mischaracterizes the enormous, historic, exhausting amount of civic activity down here. I’ve never seen the town so goddamned busy, so many sunken eyes and jittery nerves and bleeping blackberries and calloused hands. In fact, many many people did not wait and are not waiting, paralyzed, for government help, but rather are moving forward and doing. And I’d say most who are waiting for that Road Home check, aren’t just sitting on the stoop engaged in entertaining esoteric banter, they’re gutting, rebuilding, hiring contractors or doing it themselves, trying to keep from being ripped off or making ear-numbing numbers of telephone calls to try to get that check in their hands. Or just plain getting the hell out. Beckett once said he wrote out of “impotence and ignorance,” (as opposed to his buddy and compatriot James Joyce who wrote from “omnipotence and omnipresence”). His quiet acknowledgment and relentless exploration of the impossibility of the human condition eventually earned him the Nobel Prize for literature. Though everyone on the planet faces his own extinction and demise, in New Orleans we’ve had the rather rare experience, at least in America, of facing it publicly, collectively. The production made me think that a true memorial to the place, the people and the moment would be to erect permanent amphitheater-style seating on that same spot at N. Prieur and Reynes, where people could come and just look and listen and be silent. 11/16/07

The New Yorker, Hilton Als – We Wait. In New Orleans’s Lower Ninth Ward one recent evening, the New York-based arts council Creative Time and the exemplary theatre troupe the Classical Theatre of Harlem were presenting Samuel Beckett’s “Waiting for Godot,” from 1949. The brainchild of the multimedia artist Paul Chan, the production starred Wendell Pierce as Vladimir. (A New Orleans native, Pierce also appeared to moving effect in “When the Levees Broke,” Spike Lee’s documentary about the 2005 Katrina disaster.) Side by side, Vladimir and Estragon (the great up-and-comer J Kyle Manzay) stood in a field of dried weeds, as the air off the Mississippi River wafted through ruined trees and ruined houses in the night. Estragon’s cries made the six hundred and fifty or so onlookers at this free event shiver with recognition. As directed by the ever-inventive Christopher McElroen, the “Godot” seen here became, after a while, a mirror to those New Orleans natives who may or may not have given up on Godot by now, as they wait for the return of their faith. 11/26/07

Foundla.com/blog – This past Friday, I had the pleasure of attending Waiting for Godot [presented by the Classical Theatre of Harlem and Creative Time] in the Lower 9th Ward, New Orleans. The turnout was gigantic and unfortunately droves of people had to be turned away. The performance was free, and the people at Creative Time created a ‘Shadow Fund,’ matching the production budget dollar-for dollar, giving local organizations ‘rebuilding support in the neighborhoods where the play is presented.’ After hustling my way to a ticket, I entered the abandoned, overgrown lawn where a gumbo reception was taking place. Soon after, The Big 9 Social Aid and Pleasure Club led the scores of locals to the staging area, complete with a traditional second line. What followed was an accessible, humorous, stirring rendition of the Beckett classic. The entire case [Wendell Pierce, J Kyle Manzay, T. Ryder Smith, & Mark McLaughlin] were stellar. The entire stage was set outdoors, most likely where a building stood several years ago. The levee loomed in the background, framed by oak trees. An occasional boat or train could be heard moaning in the distance, and the night air became gradually cooler as the desperation of the characters mounted. Outside of the punning poignancy of the concept of the play [the characters are waiting in vain for a person, friend, deity, savior that isn’t coming or maybe doesn’t even exist — like so many stranded Gulf Coast residents during Katrina], the play was enthusiastically attended and was ultimately commissioned unselfishly by an outside artists’ organization with dueling creative and philanthropic goals. 11/6/07

[previous] [next]