Photos by Seth Freeman and Peter Ksander

Excerpts from reviews

Full reviews are below

“The story blisters to life . . . An in-your-face mix of ripped-from-the-transcripts dialogue, performance art, improv and fourth-wall shattering by Barbara Hammond and directed with rebel verve by Tea Alagic. No sitting at a polite distance in this production . . . Hammond crafts the Pussy Riot girls’ dialogue from closing statements, transcripts and prison diaries—and their speech is part defiant manifesto-bravado and part despair. . . . Their subsequent fame, championed by that master manipulator of media, Madonna—is depicted in funny but scathing scene where the glammed-up Nadya and Masha join the Material Girl in an increasingly frenzied dance to “Vogue.” . . . Their story is powerfully contrasted to that of Sergey (the excellent T. Ryder Smith), a professor on a hunger strike inspired by the Bolotnaya Square prisoners. His philosophic and poetic rambles to a doctor . . . give a weighty historic perspective. . . . Like its inspiration, We Are Pussy Riot shocks and provokes, but sometimes tries too hard . . . Yet, the saga of Pussy Riot comes through loud and clear. “ DC Theatre Scene, Jayne Blanchard

“An outstanding evening of agitprop . . . Director Tea Alagić has assembled a fine cast and worked them into an ensemble that interacts as freely with the audience as they do with each other. . . . Although a bit unfocused at times, the rough edges of this production are part and parcel with the politically charged style of theater here. Pussy Riot is not about neat narrative arcs or happy endings; their impatience for change defines them, and you wouldn’t want a show about them to betray any hint of the polish that is so often associated with the “legitimate” theater. . . . What also sets this show apart is the emphasis on the suffering of other, anonymous prisoners whom Pussy Riot encountered during their incarceration. T. Ryder Smith gives a truly unforgettable performance as Sergey, imprisoned for trying to prevent the police from beating a demonstrator. As his rage grows, Sergey goes on a prolonged hunger strike. Being a history teacher by trade, he provides a broader context for Pussy Riot’s work . . . As shocking as the proceedings already are, it is even a greater shock to realize that Hammond is not making this stuff up; she’s working from verbatim transcripts of the trial . . . There is much to admire here, both in the concept and execution of We Are Pussy Riot – but I would betray some truly wonderful secrets to discuss them here. Take it from me, this Riot is well worth the time; especially if your sense of urgency and your desire for social change is at an ebb, this show is a forceful reminder that we all have unfinished business.” MD Theatre Guide, Andrew White

“Messy but effective . . . The dynamism and the sheer energy, not to mention breathtaking bravery, of the young women at the center of the action, carry the day. . . . With all the show’s problems, including a dramatically-justified but still emotionally-deflating denial of a curtain call, audience members leave exhilarated. . . There’s a good argument to be made that a well-made play about these deliberately unpolished provocateurs would have been as much of a contradiction of what they stand for as tucking in a tribute to the Russian Orthodox patriarch. In any case: no fear, not happening here. . . .” Broadway World, Jack L. B. Gohn

“A misconceived and sometimes wince-inducing grab-bag of ideas and approaches . . . The play also features audience participation, rowdy street-theater sequences and a tale of a non-celebrity Russian political prisoner . . . Presumably, the defamiliarizing techniques and lack of continuity aim to echo the disruptive effects of Pussy Riot’s political art . . .“ Washington Post, Celia Wren

“Takes us into the spirit of Pussy Riot, into the wild energy and forceful violation of public spaces, into the group’s provocative language, and total disrespect for State authority . . . [but] even though we can admire the performers’ dedication to their roles, and the imagination and verve they bring as an ensemble to their parts, we are nevertheless left somewhat detached from the proceedings . . . Sergey is played passionately by T. Ryder Smith . . . Nadya, Masha, and Katya, are played with wonderful punk variety by Libby Matthews, Liba Vaynberg, and Katya Stepanov . . . Tea Alagić directs with verve and skill. She uses the entire Marinoff space, from the catwalks to the lobby, and the fun never stops . . . We Are Pussy Riot brings . . . Russian energy to an American stage, allowing us to witness, albeit as spectators, what it means to stand up against the oppressiveness of State power and be counted.” DCMetro Theatre Arts, Robert Michael Oliver

“An immersive and outstanding theatrical experience, filled with unique choices and the sobering undercurrent that this story is not just theatrical fiction . . . We Are Pussy Riot begins before the play actually begins. In a refreshingly unique tactic, while the audience is waiting in the lobby to enter the theater, we see Pussy Riot re-enacting their famous 2012 protest. The girl group members scream and protest inches away from the audience members and are disbanded by the actors playing police in the lobby. We also witness the beginning of the story when history teacher, Sergey, attempts to film the girls and is arrested for “interfering with police business” and “obstructing justice”. . . . T. Ryder Smith does a phenomenal job in the heart and soul of the production . . . Libby Matthews, Liba Vaynberg and Katya Stepanov as Katya each did a spectacular job in performances ripe with passion and purpose. . . . A wonderful element to the production is the staging choice to include the audience in the action as a character in the show. Characters frequently run through and around the audience, directly ask audience members questions and, at one point, cleverly pull audience members onstage to participate as witnesses in the trial. . . Smith and Nealis show off their excellent improvisational skills as they build dialogue on-the-spot around the answers the audience witnesses give. . . . An incredible piece of live theater which directly involves the audience to think about and speak up against the injustices occurring in today’s global society . . . “ Broadway World, Johnna Leary

Publicity

Above, l to r: Libby Matthews (Nadja), Katya Stepanov, (Katya), and Liba Vaynberg (Masha)

photo by the Hinge Collective

Rehearsals

Playwright Barbara Hammond

photo by Seth Freeman

Director Tea Alagic

Designer Peter Ksander

Above:

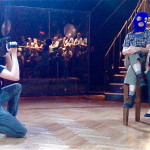

Rows 1 and 2: First day read-through. Photos by Seth Freeman.

Row 3: early rehearsals.

Row 4: Tea Alagic directing Liba Vaynberg; initiation; guest audience interviewed.

Rows 5 and 6: group improvs, re births of tyrants through history.

Row 7: Tea Alagic; Sarah Nealis and Barbara Hammond; SM Debra Acquavella.

Row 8: production assistant Sean Swords; poem by Anna Akhmatova: research wall.

Row 9: Katya Stepanov and Barbara Hammond; visiting the performance space; rehearsing lobby scene.

Row 10: lobby rehearsal; Tea in lobby; finished space.

Row 11: T. Ryder; Liba Vaynberg and Katya Stepanov; Peter Ksander adjusts set.

Row 12: Assistant director Lyto Triantafyllidou and Tea; sound designer Elisheba Ittoop; Tea with lighting desinger D. M. Wood.

Row 13: the icons which lined theatre walls; rehearsals.

Row 14: Cary Donaldson practices leap off table; Katya interviewed; actresses discuss scene.

Row 15: the set seen through metal detectors; Masha; Katya.

Row 16: Katya, Libby and Liba.

Row 17: teching prison scene; using preview audience volunteer; Nadja.

Rows 18 and 19: the character of the Prosecutor frequently took snapshots of the trial on his phone. I brought my actual phone onstage with me a few nights: these photos were taken during performances.

Context

Above: Pussy Riot collective, 2012.

Photo by Igor Mukhin

Above: The Pussy Riot performance in The Cathedral of Christ the Savior, Moscow,

February 2012.

Photo by AP/Sergey Ponomarev.

Above: Masha, Katya and Nadja on trial.

Photo by Jeremy Nicholl.

Above: Masha and Nadja, post-prison.

Above: Nadja and Masha with Madonna, Amnesty International concert, February 2014.

Reviews

DC Theatre Scene, Jayne Blanchard – Russian riot grrls rule in unruly ‘This is Pussy Riot’ at CATF. The saying goes, all you need to become a punk rock band is three chords and the truth. Russian performance artists and feminist activists Pussy Riot couldn’t play three chords but their truth—spoken loud and proud in a Moscow church in 2012—incited the wrath of Putin and the Orthodox Church and turned them into a social media cause celebre.

Their story blisters to life in We Are Pussy Riot, an in-your-face mix of ripped-from-the-transcripts dialogue, performance art, improv and fourth-wall shattering by Barbara Hammond and directed with rebel verve by Tea Alagic.

No sitting at a polite distance in this production. Pre-show, you are herded into the lobby where stern Soviet security guards prowl menacingly. All of a sudden, a gang of young women in colorful dresses, combat boots and ski masks—Pussy Riot—come roaring in, shouting blasphemous manifestos and profanity-laced chants. They are quickly hauled away and we enter the theater, through heavy security checkpoints.

Led into a Russian icon-lined space, the audience then becomes onlookers at a trial so farcical it would make Ionesco feel right at home. Nadya (Libby Matthrews), Masha (Liba Vaynberg) and Katya (Katya Stepanov) are accused of “hooliganism” and religious hatred.

The unorthodox “Three Sisters” don’t fully understand the barrage of charges against them and any chance to speak out is quickly stifled. Trapped behind a plexiglass wall, the trio is forced to watch the dismissive judge (Sarah Nealis)—who probably would have preferred they were burned at the stake right in the courtroom, to save time—the bureaucratic prosecutor (T. Ryder Smith) and the clown-like, daffy defense attorney (Cary Donaldson) go through this three-ring trial. Some audience members are even chosen to go up on stage and cajoled to play witness.

Two of the Pussy Riot girls are sentenced to two years in a labor camp (the third gets out on a technicality), but they were hardly invisible. Their act, and the subsequent YouTube video, went viral and the world celebrated their rebel-girl image—their feminist politics, not so much.

Hammond crafts the Pussy Riot girls’ dialogue from closing statements, transcripts and prison diaries—and their speech is part defiant manifesto bravado and part despair. We don’t get a clear indication of their individual personalities, but perhaps we’re not meant to, since their repeated slogan is “We Are All Pussy Riot.”

Their subsequent fame, championed by that master manipulator of media, Madonna—is depicted in funny but scathing scene where the glammed up Nadya and Masha join the Material Girl in an increasingly frenzied dance to “Vogue.”

However, their story is powerfully contrasted to that of Sergey (the excellent T. Ryder Smith), a professor on a hunger strike inspired by the Bolotnaya Square prisoners. His philosophic and poetic rambles to a doctor named Anna (Sarah Nealis), which involve other famous Annas, such as Karenina and poet Akhmatova, give a weighty historic perspective. Sergey’s tormented musings also call into play whether Russia’s repeated history of oppression and violence is predicated on a long string of iron-fisted rulers and religious persecution or is it indicative of their national character? Putin is Stalin is Ivan the Terrible, only in a westernized suit.

Like its inspiration, We Are Pussy Riot shocks and provokes, but sometimes tries too hard—you kinda lose the thread when the Pussy Riot girls cradle babies with Ivan the Terrible masks or Anna grotesquely gives birth to a fully-grown Putin.

Yet, the saga of Pussy Riot comes through loud and clear. They paid the price for their outspokenness, their outrageous performance art, but they also became famous—their likenesses revered and copied on social media, becoming the modern-day manifestation of the Russian religious icons that line the theater walls. 7.14.15

MD Theatre Guide, Andrew White – “Feminist punk can drive you crazy, but it’s worth it. Do not resist it.”

Thus spake Masha Alyokhina, a member of Pussy Riot, at the Glastonbury festival in England; last week these brave Russian women stormed the concert grounds complete with a Russian military truck (taking back the weapons of the state is one of their goals), and together they proceeded to agitate the crowd. (I would not say “entertain” – they are not in that filthy business at all.)

Although they could not join us in the USA this summer, playwright Barbara Hammond has given us the next best thing. Taking up their challenge, she has produced an outstanding evening of agitprop, We Are Pussy Riot, inspired by their famous demonstration in the Church of the Savior in Moscow and their subsequent trial at the hands of Putin’s court. Director Tea Alagić has assembled a fine cast and worked them into an ensemble that interacts as freely with the audience as they do with each other.

Although a bit unfocused at times, the rough edges of this production are part and parcel with the politically charged style of theater here. Pussy Riot is not about neat narrative arcs or happy endings; their impatience for change defines them, and you wouldn’t want a show about them to betray any hint of the polish that is so often associated with the “legitimate” theater. If nothing else, the audience’s forced procession through security scanners into the courtroom-stage is a reminder that there are parts of the ‘civilized’ world where performers can get themselves into serious trouble.

What also sets this show apart is the emphasis on the suffering of other, anonymous prisoners whom Pussy Riot encountered during their incarceration. T. Ryder Smith gives a truly unforgettable performance as Sergey, imprisoned for trying to prevent the police from beating a demonstrator. As his rage grows, Sergey goes on a prolonged hunger strike. Being a history teacher by trade, he provides a broader context for Pussy Riot’s work, as well as the long tradition of brutality and persecution Russia has suffered down through the centuries. These feminists would never want us to forget the countless victims of Putin’s regime who languish to this day, and Hammond is wise to place them center stage as well.

Libby Matthews, Liba Vaynberg and Katya Stepanov do the Feminist Punk movement credit as the trio at the core of the story – Nadya, Katya and Katya—who are hauled into court for a show trial. Under the watchful eye of a female judge (played with menacing efficiency by Sarah Nealis) both the prosecution (played with relish by Smith) and a lazy, perfunctory defense (Cary Donaldson) go through the motions of a trial without substance. As shocking as the proceedings already are, it is even a greater shock to realize that Hammond is not making this stuff up; she’s working from verbatim transcripts of the trial, and blogs posted on the Web by the women themselves.

Peter Ksander has created a fine, spare setting, punctuated by Orthodox icons on the periphery; they stand in mute witness to the complicity of the Russian Orthodox Church hierarchy in Putin’s regime; a reminder, too, that it was the Patriarch’s blessing of Putin that enraged Pussy Riot in the first place. Because the action shifts constantly from court to prison, and then to more nightmarish places, D. M. Wood’s lights guide us flawlessly and—when necessary—ominously.

There is much to admire here, both in the concept and execution of We Are Pussy Riot – but I would betray some truly wonderful secrets to discuss them here. Take it from me, this Riot is well worth the time; especially if your sense of urgency and your desire for social change is at an ebb, this show is a forceful reminder that we all have unfinished business. 7.14.15

Broadway World, Jack L. B. Gohn – The Messy But Effective We Are Pussy Riot at CATF – Based on my entirely unscientific poll, We Are Pussy Riot was the audience favorite among the five plays being staged at this year’s Contemporary American Theater Festival in Shepherdstown, West Virginia. You might not expect that kind of popularity for a show that chaotically intersperses and dilutes the story of the titular well-known Russian feminist punk protestors imprisoned for a provocation in February 2012 at Moscow’s Russian Orthodox cathedral with the much less-known story of an older male prisoner seized during the later Bolotnaya Square protests. Nor would one predict that kind of favor for a show whose script was subject to major reorganization during the rehearsal process. Yet the dynamism and the sheer energy, not to mention breathtaking bravery, of the young women at the center of the action, carry the day. With all the show’s problems, including a dramatically justified but still emotionally deflating denial of a curtain call, audience members leave exhilarated.

I think the success of the piece notwithstanding these drawbacks rests upon what author Barbara Hammond and her various collaborators at Shepherdstown get right. This includes a recreation of an actual Pussy Riot provocation/performance (which is visually all of a piece with the documentary evidence in HBO’s Pussy Riot: A Punk Prayer); excerpts from the Russian government’s show trial which rely largely on the actual words of the defendants, lawyers, and judge; and the language and attitudes of the authorities, especially the police and the judiciary, which are notorious. And overarching these, the show nails the crisis of authority and legitimacy for the Russian state and the Russian Orthodox Church, the Pussy Riot protestors helped exacerbate for a while to an acuteness sharper than even the play conveys.

When these things are working, often sparked by the infectious (and accurately portrayed) high spirits and attractiveness of the three young women Putin’s minions held to account, one tends to overlook things like the problem of deciding at any given moment whether it is a political prisoner, a prosecutor, or Vladimir Putin himself talking (all gamely but confusingly portrayed by the highly adaptable T. Ryder Smith), like determining whether the political prisoner is conversing with an examining physician or the ghost of poet Anna Akhmatova or even the judge (all played by the nearly-as-flexible Sarah Nealis). We overlook the story being told in a more phantasmagorical than representational way, just sitting back at times and let parts of it wash over us,

It’s okay. There’s a good argument to be made that a well-made play about these deliberately unpolished provocateurs would have been as much of a contradiction of what they stand for as tucking in a tribute to the Russian Orthodox patriarch. In any case: no fear, not happening here. In fact, the play doesn’t even hold still long enough to end with a tableau of some sort showing our three heroines as heroines.

Instead, by portraying two of them after their release from prison cozying up to and performing with Madonna, the show poses some hard questions about the responsibilities young heroes and heroines shoulder when their first youthful triumphs are behind them. So far as I can determine, this part is fiction; two members of the group did appear on stage with Madonna, but only to speak. Still, others in the Pussy Riot collective sought to eject them because of this supposed apostasy from the anarchist ideal, so it obviously struck a nerve. But no one can stay young forever. Nor can the demands of fame be easily evaded. Would it have been selling out to perform with Madonna, had that really happened, especially when Madonna had earlier, during the show trial, turned up the heat on the Russian government by giving a concert in Moscow flaunting a message supporting the defendants written on her back? Tough question, and one the members of Pussy Riot will increasingly confront in real life as time goes on. The struggle to change Russia is not going to stop, and the Pussy Rioters will certainly be looked to for leadership, or comment, or at least example for others to emulate. So I think this was a fine question to pose near the end.

Let me, in parting, tip the hat to Libby Matthews, Liba Vaynberg, and Katya Stepanov, pictured left to right above, for their fine portrayals of the heroines Nadya, Masha, and Katya, respectively. They astutely captured and shared the good cheer, determination, and sheer guts of the women they portrayed.

This is the world premiere of We Are Pussy Riot. The play will require some polish in subsequent productions. But I honestly hope it does not receive too much. 7.14.15

DCMetro Theatre Arts, Robert Michael Oliver – Pussy Riot, punk truth-tellers and guitar-playing agitators and feminist rabble-rousers who stood up to the Russian State and its Church affiliates under Vladimir Putin. They went into Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Savior and staged a demonstration against the Orthodox Church’s support for Putin; Patriarch Kirill of the Russian Orthodox Church said that they did the devil’s work. They were arrested and eventually 2 of the 5 were sent to prison for “hooliganism.”

We Are Pussy Riot by Barbara Hammond and commissioned by the Contemporary American Theatre Festival, is now being given its world premiere. It takes us into the spirit of Pussy Riot, into the wild energy and forceful violation of public spaces, into the group’s provocative language, and total disrespect for State authority.

Or at least We Are Pussy Riot attempts to do so.

The challenge is: we aren’t in Russia, and the issues that might spark a riot there, won’t spark a riot here. So, even though we can admire the performers’ dedication to their roles, and the imagination and verve they bring as an ensemble to their parts, we are nevertheless left somewhat detached from the proceedings. We might sympathize with the plight of individual rights in Russia; we might even detest Putin and his style and his results; we might even consider Russia hopelessly oppressive to women, gays, and lovers of free market capitalism; but the visceral force that is Pussy Riot will have not been felt, because the causes they fight for are realities not concepts, and their realities are in Russia. So even though playwright Hammond makes a valiant effort at play’s end to make Pussy Riot meaningful to us, that meaning remains conceptual without material, emotional force.

We remain distant spectators, even if, like myself, we might spend our lives protesting state oppression and imperialism, and unjust imprisonment, political show trials (or Grand Juries) and torture, committed in the US, by state and federal and county governments.

In other words, the problem with We Are Pussy Riots lies not in the form, but in the content.

On several occasions during the play the Pussy Rioters declare that if what we in the audience were watching weren’t theatre but a protest, then we’d be outraged, offended, or otherwise emotionally engaged.

The problem with that assertion is simple: protest–particularly the kind the Pussy Rioters do–is theatre, theatre without a ticket, theatre in the open among the people, in the public square. It is theatre that attacks the visceral issues of the day, without clever aesthetics or America’s “No Politics Allowed” rule for playwrights.

In other words, what is lacking in We Are Pussy Rioters is not the form, but the content.

If the Pussy Rioters had asserted that, like the protesters of the 1960s, that the US government was a fascistic imperial power run for the rich, by the rich, and of the rich, they might have offended a few people, which would have been evidenced by them walking out of the Marinoff Theatre.

If the Pussy Rioters had asserted that, like the “Black Lives Matter” movement that police forces all across America are becoming increasingly militarized and racist and are murdering men and women of color with relative impunity, they might have offended a few people, evidenced by angry outbursts coming from audience members as they defend the police who “have a tough job to do.”

Even if the feminist Pussy Rioters had, like Sinead O’Connor in 1992, gone center stage and torn a picture of Pope John Paul II, declaring him evil for his acceptance of child sexual abuse within the Catholic Church, they would have definitely popped a few eyebrows; but, given that that is old news today and generally known as true (unlike in 1992), the Pussy Rioters probably would not have had to go behind the producers backs to pull it off. Also, their careers would not have effectively been ruined in the US, as was Sinead O’Connor’s.

Absent a parallel protest, however, that connects what the Pussy Rioters do in Russia to what they would do if they were US citizens living in America, then We Are Pussy Riot remains an object lesson on what those bad Russians do and becomes a tame, twisted version of It Can’t Happen Here.

Hammond constructs her play around two stories: 1) the imprisonment of a history teacher named Sergey and 2) the show trial of three Pussy Rioters for the above mentioned hooliganism.

Sergey is played passionately by T. Ryder Smith. Sarah Nealis plays Anna, the doctor who is charged with caring for him. She becomes equally impassioned to save him, for Sergey is starving himself to death, as a protest against false imprisonment. Remember the Guantanamo prisoners who were starving themselves to death, demanding after a decade of imprisonment either a trial or release (they were force-fed by the US military).

Hammond elects to do the show trial as Agit-Prop theatre; in other words, it is farcical and in your face with its broad strokes and over-blown acting style. The Agit-Prop style allows her to bring in the real life testimonies of Rioters Nadya, Masha, and Katya, played with wonderful punk variety by Libby Matthews, Liba Vaynberg, and Katya Stepanov.

A large ensemble fills out the cast, playing a variety of attorneys, rioters, and even Putin himself: Cary Donaldson, Allyson Jean Malandra, Keyla McClure, and Brianne Taylor.

Someone even puts in a turn as Madonna who, in real life, lent her support and solidarity to Pussy Riot at a charity concert in New York City for Amnesty International. Ironically, back home in Moscow, Pussy Rioters were protesting the concert and Pussy Riot’s participation because tickets were sold to the event, something Pussy Riot adamantly denies itself: protesters do not earn money from performances.

Tea Alagić directs the performance, and does so with verve and skill. She uses the entire Marinoff space, from the cat walks to the lobby, and the fun never stops.

The production team also does a fine job. Sets by Peter Ksander are flexible and open to change. Costumes by Trevor Bowen are colorful and, perhaps, a bit too perfect. And lights by D.M. Wood help direct our attention.

Few would deny that we live under an increasingly powerful totalitarian apparatus of control. In Russia, Putin is the face of that State authority. In America, for large swathes of Americans, Obama is the dictator with absolute power (before him it was Bush and Cheney [Dr. Death] who welded the levers of total war). All across the world, the power of an increasingly robotic army threatens.

All across the world individuals either stage protests in churches and spend two years in prison, or light themselves on fire in the public square and cause a revolution, or lock themselves together arm-in-arm to block a highway, only to be carted off to jail.

We Are Pussy Riot brings that Russian energy to an American stage, allowing us to witness, albeit as spectators, what it means to stand-up against the oppressiveness of State power and be counted. 7.31.15

Communities Digital News, Terry Ponick – Politics, prose and chaos. Somewhat like CATF’s controversial 2007 production of “My Name Is Rachel Corrie,” the 2015 world premiere production of Barbara Hammond’s “We Are Pussy Riot” may unintentionally raise a barrier for those members of the audience not on top of the latest international pop entertainment happenings or recent international political scandals.

Who is Pussy Riot?

While the title of this play might seem deliberately designed to shock, that’s not necessarily the point. “Pussy Riot” refers to and is actually about—more or less—the antics of a Russian feminist-anarchist, anti-capitalist 20-something punk rock band-collective that perform(s) under that name.

Intriguingly, band members chose from the beginning to spell out their moniker not in Cyrillic but in the Western (Latin) alphabet as either a provocatively pro-Western gesture deliberately meant to antagonize the current Russian oligarchy, attract the attention of Western rockers, entertainers and media, or perhaps both.

Though this somewhat fugitive, sometime band has its musical supporters, a great many critics both in Russia and abroad regard them as pretty lousy musicians. This hasn’t much bothered them, however, for, it seems, their primary mission is protest politics. They strive to stage—without authorization or permission—brief, attention-grabbing “guerilla performances” of musical street theater when and where individuals and the Russian authorities would least expect them.

At various times, members of the group have expressed support for feminism, anarchism and LGBT rights, while at the same time shouting their opposition to Russia’s current President-for-Life, Vladimir Putin, his current, KGB-inspired Russian thugocracy, the currently government co-opted Russian Orthodox Church and, of course, rapacious Western capitalism.

Like Marlon Brando’s motorcycle gang leader in the 1953 film classic, “The Wild Ones,” if you chanced to ask Pussy Riot what, exactly, they are rebelling against, Pussy Riot might fire back, “What’ve you got?”

Pussy Riot’s antics put them under the watchful eye of Putin’s authorities. But when things really got interesting was in February of 2012 when five members of the band dashed into Moscow’s then mostly-empty Russian Orthodox Cathedral of Christ the Savior, donned their trademark, multi-colored balaclavas, mounted the steps before the altar and began jumping and fist-pumping, singing and shouting obscenities as they delivered their latest pot-stirring anthem, “Punk Prayer: Mother of God, Drive Putin Away!”

Reportedly, they were thrown out of the cathedral by authorities within less than a minute of launching their stunt. But a clip taken from that performance was quickly edited into a video for the song that almost instantly went viral around the world.

Predictably, Putin’s authorities arrested three members of the band in March, 2012, charging them with that Soviet-era show-trial favorite—“hooliganism”—jailing all three and denying them bail.

Two band members were ultimately sentenced to two years in prison and promptly shipped off in October to one of the old Soviet Era’s gulag-prisons. Under mounting international political pressure, often spearheaded by pop music idols, these two women were given early release in 2013, though they defiantly continued to raise an occasional ruckus, most notably by attempting to disrupt ceremonies at the 2014 Winter Olympics held in Sochi.

Are We Pussy Riot?

Given the title of Hammond’s play, that’s evidently the question the audience is supposed to ask itself.

The play actually begins when you least expect it, replicating in a clever way the shock those few Russian churchgoers must have experienced when members of Pussy Riot invaded the Cathedral of Christ the Savior to deliver their own deliberately blasphemous hymn of dispraise.

We won’t tell you exactly how this happens. But for better or for worse, this unusual dramatic prelude may actually be the high point of a drama that quickly seems to lose its focus.

Before we are even introduced to those Russian mistresses of mayhem, we actually spend a considerable amount of time and background with a hunger-striking Russian prisoner who was arrested when he tried to prevent Russian authorities from brutally beating a group of young protesters.

Hammond’s “Sergey”—whose name has been changed in the play to conceal the name of this real-life character—is a scholar, historian and philosopher who, consistent with his studies, retains an almost encyclopedic memory that consolidates and contextualizes all of Russian history, from ancient to contemporary.

The character of Sergey (T. Ryder Smith) seems intended by the playwright to function as a chorus of sorts, representing the long-suffering, long-enduring Russian people, similar in a way to the manner in which Mussorgsky employs a chorus of peasants in his operatic masterpiece, “Boris Godunov.”

Whether unfortunately or intentionally, however, Sergey ends up occupying far too much time, space and dialogue in this play to the point where we begin to wonder whether this story is really about Sergey, Pussy Riot, or the endless suffering of all who inhabit Mother Russia.

Further awkwardness is introduced when Sergey’s increasingly sympathetic prison doctor (Sarah Nealis) morphs into the ghost of Russian Poet Anna Akhmatova—a transformation that occurs after Nealis swaps her white lab coat for a black robe to become the presiding judge at the Pussy Riot trial, all of which causes us to lose focus on who, exactly, these characters really are.

Even more problematic is the fact that the introduction of the Akhmatova character seems to have been contrived solely to introduce a few salient quotes from the poet. It’s all part of the distraction that begins when Sergey and his meditations on history seem to be taking over from what we thought was the central premise of the play.

Sergey’s character is, in fact, far more carefully developed than the characters of Hammond’s trio of Pussy Rioters, Nadya (Libby Matthews), Masha (Liba Vaynberg), and Katya (Katya Stepanov). The three young women appear furtively and episodically throughout the play, but only long enough to deliver short yet articulate protests to the judge and the prosecutor (portrayed with a brief costume change by T. Ryder Smith) and their goofball defense attorney (Adam H. Phillips).

On a few other occasions, Nadya, Mash and Katya don their signature, brightly-colored balaclavas and invade the audience shouting slogans and firing off provocative questions, amidst noise and flashing lights.

But in the end, we never really get to learn who these angry young women actually are or what they really stand for. Instead, we mostly get the pronouncements and slogans the trio rolls out with as much ease as Boomer new left protesters fired off anti-war slogans here in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

We instinctively want to be sympathetic to the young women’s cause, but we’re given precious little in this play that would cause us to readily identify with them. If, as this play’s title would seem to imply, we are supposed to be one and the same in mind and spirit with Pussy Riot, we don’t actually get much to identify with.

Leading things further astray, the play’s time-jumping, stream-of-consciousness narrative trajectory is further confused by periodic song-and-dance and dramatic scenes that attempt to give us a sense of the international support accorded Pussy Riot by prominent members of the pop music establishment.

These bits include a simulated cameo appearance by “Madonna,” who materializes on a catwalk high above the audience to denounce the establishment, support Pussy Riot, but ultimately, it seems, to boost her own increasingly tired and tedious career by creating the appearance of virtue.

If our review at this point appears to be going far afield, perhaps it is. But that’s because we’re trying to re-create the grab-bag sense of confusion that dominates the muddled narrative of this play, leaving us wondering, in the end, what it was all about and why we should even care about a trio of provocateurs whose final philosophical position seems to center on a hatred or dislike not just of Putin but of everything else. “What’ve you got?”

Ironically, aside from that stunner of an opening scene, the one other thing “We Are Pussy Riot” has going for it is an unusual segment that takes place once the trial scene gets underway. As it is several times during the production, the theater’s “fourth wall” is broken down again, but in a novel way, when the prosecutor grabs a couple of apparently random audience members and plunks them down on the witness chair to serve as witnesses for the prosecution and against the young women.

This is obviously going to be a random happening at each performance. But when we attended the play, the chosen audience “witnesses” politely but efficiently evaded the prosecutor’s attempt to lead them. Perhaps in real life, they are Federal employees or contractors well familiar with the evasive nature of Washingtonspeak. But in any case, the exchanges were hilarious as the cast members stoutly tried to keep their prosecutorial railroading on track.

“We Are Pussy Riot” is an interesting, provocative and timely concept that for once spends its time attacking Russia’s post-Soviet, anti-artistic freedom oligarchy instead of blasting our own much freer society. But Hammond’s play loses its narrative track early and often and may not be able to proceed much further without a serious reconceptualization and focus on character.

It’s entirely possible this play’s confusing forward motion is in and of itself an attempt to convey the sheer anarchy that drives so much of what is called performance art today. But even if this is the case, many audience members are still likely to end up leaving the theater more than a bit bewildered and with as little comprehension of Pussy Riot and contemporary Russia as they had when they filed in.

Broadstreetreview.com, Mark Cofta – In her Howlround essay “New Plays and the Destructive Cult of Virginity,” Carolyn Gage explains a theater phenomenon that boils down to this: some cachet (but not cash) is earned by theater companies by producing world premieres — but then few of these deflowered plays receive second productions.

The Contemporary American Theatre Festival (CATF) in picturesque Shepherdstown, WV has grown over 25 years while producing only new plays — this year, four world premieres and one (barely) non-virgin. Surviving, let alone thriving, through only new plays is very difficult. No Philadelphia theater does it, though many produce premieres; the last professional company to do it was the late 1980s-90s Philadelphia Festival Theatre for New Plays (founded by BSR contributor Carol Rocamora).

The National Network for New Plays (NNPN) counters this by arranging “rolling world premieres,” in which a new play is staged by several companies around the country, giving it more development and exposure and hopefully allowing it to jump the gap from precious virgin to respected established play. As Gage explains, this is otherwise nearly impossible, unless there is without a strong premiere production involving a major company, a large media market, and/or rave reviews.

Distraught mother, brainwashed daughter

CATF participates in NNPN, represented last year by Philadelphia playwright Thomas Gibbons’s Uncanny Valley (also produced by InterAct Theatre Company), and this year by Steven Deitz’s creepy thriller On Clover Road.

This smart twisted drama, directed by CATF artistic director Ed Herendeen, is set in an abandoned motel, where a deprogrammer (Lee Sellars) brings a distraught mom (Tasha Lawrence) to prepare for the liberation of her 17-year-old daughter from a cult.

Everyone lies and harbors disturbing secrets, and the action builds suspensefully despite some awkward stage combat on opening night (more distressing to me than the brutal violence it tries to portray!), and a compromised ending that abruptly flips the tone. Still, I loved it.

Johnna Adams’s Gidion’s Knot started at CATF in 2012 and was a Barrymore Award-winning InterAct hit, so I had high hopes for her new play World Builders. I wasn’t disappointed. This love story — staged in the round in CATF’s studio theater by Nicole A. Watson — features two psychiatric patients who, yes, fall in love, while also coping with the experimental drug that may “cure” (i.e., erase) their imaginary worlds. Terrific performances from Chris Thorn and Brenna Palughi navigate this tricky territory effectively.

Rollicking fun, shocking tragedy

Sharing a stage with On Clover Road (CATF is a rep theater, with two plays each in two of its three theater spaces, which allows seeing all five plays in only two or three days) is Sheila Callaghan’s ambitious Everything You Touch. Callaghan has been well represented locally by That Pretty Pretty; Or, The Rape Play (Theatre Exile) and Crumble (Lay Me Down, Justin Timberlake) (Flashpoint Theatre Company). May Adrales’s production and Peggy McKowen’s costumes makes glorious spectacle of 1970s high fashion in New York through moody designer Victor (Jerzy Gwiazdowski) and his assistant Esme (Libby Matthews), but the dark comedy primarily concerns present-day IT drone Jess (Dina Thomas), whose fantasies are framed by six models playing not only passersby but furniture. Her adventures, which reveal her connection to Victor, are rollicking fun punctuated by shocking tragedies, though some major characters feel perfunctory and undeveloped.

Everything You Touch, CATF’s sole not-premiere production, premiered last year in Pasadena produced by The Theater@Boston Court and Rattlestick Playwright’s Theater. How many people in West Virginia — or Philadelphia, for that matter — flew out to catch it? This is the quandary Gage dissects: for most plays, a second production is nearly impossible to get, though a play only once produced is obviously still “new.” CATF does a mitzvah by producing this play.

A pretentious mess

Two plays share the Marinoff Theater, a flexible black box arranged this summer with audience on four sides, and they represent the range of new plays (which are always a gamble) at CATF. At one end of the quality spectrum is Barbara Hammond’s commissioned WE ARE PUSSY RIOT, a play cobbled from public domain statements, trial transcripts, and online publications.

Unfortunately, director Tea Alagic’s staging is a pretentious mess: the audience crams into the small lobby until curtain time, when Pussy Riot runs through, creating a “happening.” We’re finally given access by actors playing Russian guards, and find a male prisoner onstage (T. Ryder Smith as Sergey) who engages us in discussion. “What did you think of that little demonstration” he asks, “did it offend you?”

Some predictably sheepish audience participation leads to Pussy Riot’s Kafkaesque trial, with audience dragged up as “witnesses.” Leaving the dialogue to random patrons seldom works, and I squirmed. “Madonna” and Pussy Riot screaming and dancing on the catwalk above us later didn’t help. The show ends without a curtain call, the kind of sophomoric gesture that every college student briefly thinks profound, but (hopefully) soon realizes does not work; the audience just feels cheated out of applauding and clueless about what’s happening. “What, is the play over?” is not a satisfying or illuminating ending.

Cozy and wacky

Much more accomplished is Michael Weller’s The Full Catastrophe, a comedy based on David Carkeet’s novel, directed by Herendeen. Tom Coiner — appropriately unctuous as On Clover Road’s cult leader — plays a hapless linguist hired by eccentric billionaire Roy Pillow (Sellars) to study marriage. Armed with a thick binder of instructions, he’s placed with Beth (Helen Anker), Dan (Cary Donaldson) and their son Robbie (Sam Shunney) to save their marriage. His efforts, dictated by Pillow’s daily instructions, provided in sealed envelopes, make a mess of things, as does his desire for Beth, who reminds him of old girlfriend Paula, also played by Anker in flashbacks. PUSSY RIOT’s Smith shows up again as everyone else the linguist meets, including several women, which is always good for laughs. The play combines a romantic comedy’s predictable coziness with wacky musings about billionaires and commitment. It’s not the season’s most ambitious play, but it might be its most complete script and self-assured production.

Picking risks

All in all, CATF’s season is as diverse and solid as any regional theater’s season is likely to be. Producing five new plays is much riskier than the regional formula (a classic, a musical, a recent Off-Broadway hit, a black play, etc.), but the results are similar. The challenge is for the company — and the audience — to commit to sharing different risks. Producing Hamlet, for example, is no slam-dunk either: it comes with a huge reputation and 400 years of heavy history. All theater is risky.

Will we ever see an all-new-play company in Philadelphia? With so many theaters producing new plays, as well as the unique presence of developmental company PlayPenn (which has sent several plays to CATF; their conference of free readings continues through July 26), we’re pretty close. Orbiter 3, a company formed by playwrights to produce their own new work, just premiered its first of six new plays, James Ijames’s Moon Man Walk.

Meanwhile, CATF is merely three hours away and Shepherdstown and its historic countryside make a great weekend trip. 7.21.15

Washington Post, Celia Wren – 2015 Contemporary American Theater Festival sets the stage for rebellion. Now celebrating it’s 25th season, the prominent annual showcase for recently-minted plays is presenting five works that deal with small groups of renegades bucking the status quo. The scripts are no terribly satisfying, mostly falling into the spectrum that connects the flowed-but-interesting with the sleek-but-unremarkable. Still, as is invariably the case at the festival, the performances are top-notch. And frequent theatre-goers may particularly enjoy rooting for the repertoire’s insurgent protagonists. After all, in our society theatre itself is something of an insurgent art form, struggling against the dominance of screen entertainment.

Perhaps not coincidentally, the rebellion of creative people is the subject of two of the festival’s more intriguing plays: Johnna Adams’s “World Builders” and Sheila Callaghan’s “Everything You Touch.” “World Builders” is less taut and vivid than Adams’s harrowing “Gidion’s Knot,” which premiered at the 2012 festival, but it does share the earlier play’s concerns with loss, freedom and the possibilities of transgressive imagination.

Directed by Nicole A. Watson, “World Builders” focuses on Max (Chris Thorn) and Whitney (Brenna Palughi), who are enrolled in a clinical trial for a new psychiatric drug. Both characters have schizoid personality disorder and are given to obsessing over imaginary worlds. As the two develop feelings for one another, they also confront the fact that their new medication may kill their fantasy lives.

Adams hasn’t found a way to make Max and Whitney’s fantasy experience as powerful to the audience as it is to the characters themselves, so the talked-about loss of it registers intellectually but not emotionally. The play also takes too much time to wind up and down. Still, Thorn and Palughi ace the job of showing how the drug gradually affects their characters’ perceptions and mannerisms. And although “World Builders” may be emotionally underwhelming, it does pose profound questions: Who gets to decide what it means to be a fulfilled human being? W, such as who defines what is normal?.

The question of what’s normal — as opposed to what’s elite or exceptional — also figures in Callaghan’s “Everything You Touch,” a smart but diffuse tale of haute couture, family and the importance of self-esteem. Victor (Jerzy Gwiazdowski, radiating prickliness) is a self-absorbed designer in 1970s New York who — shockingly, to his fellow fashionistas — experiments with creating clothes that ordinary people might actually wear. About four decades later, Jess (Dina Thomas), a dumpy computer geek, musters the courage to visit her dying mother. Toggling back and forth in time, the play teases out the connection between the two characters.

Directed by May Adrales, with costumes by Peggy McKowen (the festival’s associate producing director), “Everything You Touch” begins with a breathtaking sequence in which a New York trash heap morphs into a runway of models in outlandish garb. (David M. Barber designed the stylized cityscape.) And that scene isn’t the show’s only eye-catching touch: Throughout the play, the performers who depict models double as elements in Jess’s physical environment — holding out a hand to depict a car’s rear-view mirror, for instance. The conceit underscores one of the play’s themes: While some beautiful individuals may revel in the public’s gaze, others can feel simultaneously objectified and ignored.

First staged in Pasadena, Calif., in 2014 (it’s the only festival offering this year that isn’t a world premiere), “Everything You Touch” brims with ideas and rich language, but it runs low on dramatic conflict.

That’s not a problem with Michael Weller’s comedy “The Full Catastrophe,” based on a novel by David Carkeet. The play follows Jeremy Cook (Tom Coiner), an amiable linguistics scholar recruited by a maverick billionaire named Roy Pillow (Lee Sellars), to take part in an iconoclastic research experiment.

Pillow thinks he has found a way to fix foundering marriages: embed a linguist in the household to spot, and correct, miscommunication between spouses. As Jeremy discovers, that strategy is trickier than it sounds. Installed in the home of Beth and Dan Wilson (Helen Anker and Cary Donaldson), Jeremy manages to infuriate both his hosts and Pillow. Moreover, his romantic past returns to haunt him.

Given a polished look and pace by Ed Herendeen, CATF’s producing director, with actor T. ryder Smith supplying a series of hilarious cameos (as a bartender, a courier, and more), “The Full catastrophe” is the 2015 festival’s most successful production, but it feels a bit lightweight.

Another burnished piece, Steven Dietz’s “On Clover Road” directed by Herendeen, is a grom twisty, and none too memorable thriller about a cult.

The biggest disappointment is the high-profile festival commission “We Are Pussy Riot,” a misconceived and sometimes wince-inducing grab-bag of ideas and approaches, written by Barbara Hammond and directed by Tea Alagić. The play deals with the 2012 trial and conviction on hooliganism charges of members of Pussy Riot, the celebrated Russian protest group and punk band that staged a political stunt in a Moscow cathedral.

In a program note, Hammond writes that the dialogue in her trial scene is lifted almost exclusively from transcripts and that other lines reproduce public statements made by Pussy Riot members, Russian leader Vladimir Putin and other figures. That documentary-style strategy could have been powerful, but this production adds stylistic elements that distract from, and even seem to trivialize, the historical testimony.

For instance, in the trial scene, when the prosecutor (Smith) reads out the charges, a burst of beatific choral singing rings out and the lighting pins him with a halo-like spotlight. At another point, as Nadya, Masha and Katya (Liby Matthews, Liba Vaynberg, and Katya Stepanov) make courtroom statements, the lawyers, (including Donaldson as the defense attorney) slither from their chairs and lie prone on the floor.

The play also features audience participation (on opening night, one poor patron was marched onstage and grilled about her religious beliefs), rowdy street-theater sequences and a tale of a non-celebrity Russian political prisoner (Smith). Presumably, the defamiliarizing techniques and lack of continuity aim to echo the disruptive effects of Pussy Riot’s political art.

But the show’s theatrical bells- and- whistles ultimately come across as incoherent and self-indulgent, overshadowing the activists’ original act of witness. 7.14.15

A Honey of an Anklet blog – We Are Pussy Riot, by Barbara Hammond, brings new life to the expression “show trial.” The play provides a context for the antics of the provocative Russian feminist group, a punk artist collective whose means and motives are easily misinterpreted by Western media.

The piece incorporates a jumble of overtly theatrical elements, some more successful than others: exaggerated gesture, lines spoken as a chorus, audience participation, a dance break with Madonna (who has spoken publicly in support of the group). If the pre-show in the cramped lobby of the Marinoff is a muddle, the cast are quick on their feet in dealing with audience members. (On premiere night, T. Ryder Smith, as Russian prosecutor, gave somewhat willing volunteer Paul a sheet of charges to read; when Paul begged off, saying that he needed his reading glasses, Smith bounded back to Paul’s companion in search of the specs.)

The scenes of the 2012 trial of three members of Pussy Riot, with dialogue taken almost exclusively from public statements, are interleaved with scenes in the cell of dissident Sergey (Smith, again), a composite character. While we are left with the impression that the young women’s movement will prove to be a flash in the pan, the passages with Sergey give the play gravity, bringing all that dancing on the catwalk back to earth. Russia’s problems and injustices aren’t going away soon, and maybe this kick in the shins from these young women with their guitars and video cameras will spark something of lasting impact. 7.13.15

[previous] [next]