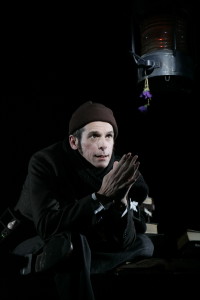

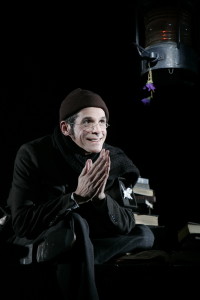

Photos by Carol Rosegg

Above, top: Back row: Ron Cephas Jones, Maria Dizzia, Steven Mellor, Veanne Cox, Ana Reeder. Front row: Lou Cancelmi, T. Ryder Smith, Adam Rothenberg, Jayme Dornan. Bottom photos: T. Ryder Smith

Excerpts from the reviews

Full reviews are below

“Glen Berger’s whimsical sendup of British folk tale traditions, “The Wooden Breeks,” isn’t entirely without point, although our contempo culture hardly seems in need of cautionary tales about sexual repression. But the pleasure principle is shot to hell by the dreary storytelling, helmed by Trip Cullman with the sensibility of some effete intellectual marched off to the Gulag to put on a show for political prisoners. . . Despite its interminable length (135 minutes feels like eternity) and repetitive jokes (enough with the grave-robbing), the text is stylishly written and comically rendered in thick Scottish accents by thesps properly prepped by dialect coach Stephen Gabis. But whatever is genuinely clever about the piece leeches out in production. . . The show’s only textures are those tonal ones that the actors manage to find in the language –an advanced skill at which precious few of them are adept. Veanne Cox has the most noticeable success at this trick, dropping her voice to cello level and stroking every word like a musical note. Smith is also completely at home in his lighthouse aerie, surrounded by his books and loving every ludicrous word he comes across . . . a deliciously droll turn.” Marilyn Stasio, Variety

“A lone figure sits hunched over a fading fire as the audience enters the theater, searching in the embers for the answer to the question that has left him ill-shaven and hollow-eyed. Tom Bosch is a downcast fellow brooding on the betrayal of the faithless Hetty, who loved him, left him for a sailor, loved him again and then left him for good nine years ago. Held in thrall by the “magical” fire that’s been smoldering before him ever since, Bosch has whiled away the endless hours by telling stories to himself and the bastard child Hetty left behind, tales in which he manufactures far-fetched explanations for her delayed return. Drained at last of hope that Hetty will come back, as promised, before the fire dies, Bosch tries to douse the flames and break the spell, but they burn on. He’s forced to add another chapter to the saga, and so conjures up the mythical village of Brood. The fire’s last, undying ember becomes the flashing beacon in the town lighthouse, and Bosch, desperate to reassert control over his life, will spend the rest of the play trying to enter his fictional world, put out the light and free himself from the task of tale-telling forever. Or something like that, anyway. . . ” Charles Isherwood, The New York Times

“I’ve heard it said that whimsical fantasy is just about the hardest thing to pull off in the theatre. Certainly the creative personnel involved with staging Glen Berger’s remarkable play The Wooden Breeks at MCC Theater have done just about everything in their power to negate the pixilated, otherworldly charms of the piece and turn it into a leaden, heavy catastrophe. . . “ Martin Denton, nytheatre.com

Publicity

Full reviews

New York Times, Charles Isherwood – Each Trapped in a Box, Trying to Think Outside It. The line dividing inspired whimsy from tedious nonsense can be a fine one, and much of “The Wooden Breeks,” a new play by Glen Berger, falls on the wrong side of it. This elaborately conceived comedy, which opened last night at the Lucille Lortel Theater in an MCC Theater production, seeks to celebrate the consolations of storytelling through the saga of a Scottish tinker who dreams up imaginary worlds to keep despair at bay. But it’s more the pitfalls of narrative, rather than its rewards, that Mr. Berger succeeds in demonstrating. A lone figure sits hunched over a fading fire as the audience enters the theater, searching in the embers for the answer to the question that has left him ill-shaven and hollow-eyed. Tom Bosch (a nicely sardonic Adam Rothenberg) is a downcast fellow brooding on the betrayal of the faithless Hetty (Ana Reeder), who loved him, left him for a sailor, loved him again and then left him for good nine years ago.

Held in thrall by the “magical” fire that’s been smoldering before him ever since, Bosch has whiled away the endless hours by telling stories to himself and the bastard child Hetty left behind, tales in which he manufactures far-fetched explanations for her delayed return. Drained at last of hope that Hetty will come back, as promised, before the fire dies, Bosch tries to douse the flames and break the spell, but they burn on. He’s forced to add another chapter to the saga, and so conjures up the mythical village of Brood. The fire’s last, undying ember becomes the flashing beacon in the town lighthouse, and Bosch, desperate to reassert control over his life, will spend the rest of the play trying to enter his fictional world, put out the light and free himself from the task of tale-telling forever. Or something like that, anyway. Mr. Berger’s elaborate framework has obviously been carefully constructed with an eye toward making clever points about the magic, the madness and the meta- of fiction, but audiences are not likely to take much pleasure in his handiwork. They’re generally more interested in the quality of the tale being told than in the reasons for its telling. And, not having Bosch’s intense interest in the narrative in question, they will probably be baffled or bored by his unnecessarily intricate story of romantic misadventures in Brood. For while they are embodied with winning verve by a talented cast under Trip Cullman’s direction, the fanciful folk of this strange town are less full-bodied fictions than 19th-century templates for the supporting characters in television sitcoms. Jarl von Hoother (T. Ryder Smith) is the reclusive lighthouse keeper who spends his days sipping tea and rummaging amid his store of arcane books. The vicar Enry Leap (Steve Mellor) is secretly besotted with Mrs. Nelles (Veanne Cox), the prim proprietress of the only public house, who has shut her doors in mourning for her dead daughter, Lavender. A rival romance blooms between the pert laundress Tricity Tiara (Maria Dizzia) and her mustachioed swain, Armitage Shanks (Louis Cancelmi). (Beats me why this character is named after a bathroom-fixtures manufacturer, although a joke in the play has him stuck in the town “privy.”)

As their cute names (and cuter costumes by Anita Yavich) imply, these characters speak in colorful pseudo-brogues, allowing Mr. Berger to display a specialist’s affection for the quaint speech patterns of yore. A similar affection for historical arcana figures in the complicated plot, cantilevered upon the arrival in Brood of a saleswoman hawking a contraption known as a bell device. These ghoulish novelties, briefly popular in 19th-century Britain according to a note in the script, were designed to placate fears of being buried alive. If you woke up to find yourself prematurely interred, you tugged a string attached to a bell hung above your coffin, and the little error could be rectified.

Mr. Berger makes much metaphorical hay with this macabre tool. Characters find themselves stuck in all sorts of boxes, emotional, psychological and literal, and there is a complicated subplot about the townsfolk’s attempts to solve the riddle of a locked box. The play’s title, for the record, is a Scottish slang term for a coffin, “breeks” meaning britches. And yet the layered patterns of imagery in the play won’t mean much to audiences looking merely to be engaged by a story, not dazzled by filigreed dramaturgy. Mr. Berger is the author of the popular solo play “Underneath the Lintel,” which also unfolded a woolly saga full of peculiar events. He is plainly enamored of the seductions of a good story, the fancier the better. But in “The Wooden Breeks” Mr. Berger sacrifices the one crucial element in the art of fiction — human interest — to a muscular display of narrative prowess. More exhausting than entrancing, the play squanders more than two hours of stage time to spin a yarn that does not, in the end, convince us that it’s worth spinning. 2-22-06

Variety, Marilyn Stasio – Story theater can be charming. So can children’s theater, folk theater and fairy tales. But there has to be some point — and surely some pleasure — in modifying these forms for enjoyable adult consumption. Glen Berger’s whimsical sendup of British folk tale traditions, “The Wooden Breeks,” isn’t entirely without point, although our contempo culture hardly seems in need of cautionary tales about sexual repression. But the pleasure principle is shot to hell by the dreary storytelling, helmed by Trip Cullman with the sensibility of some effete intellectual marched off to the Gulag to put on a show for political prisoners. (Fair warning: The plot sounds a lot more entertaining in precis than it does when experienced from a hard theater seat.) The storytelling framework positions the yarn in the 19th-century Scottish village of Clekan-wittit, where a lovelorn tinker named Tom “Chimney” Bosch (Adam Rothenberg) is warming himself by a fire and brooding over the cruel trick played on him by his beloved Hetty Grigs (Ana Reeder), who ran off with a sailor and left him with her bastard son Wicker (Jaymie Dornan), along with the false promise she would return before the last flame of his fire burned out. Years pass. To shut up Wicker, who has grown to be an annoying lad (though played with boyish charm by Dornan), Bosch agrees to tell one last tale in the continuing story cycle he has been spinning to explain Hetty’s tardiness. (In Chapter 53, she is distracted by “an enormous and carnivorous haddock.”) But he is determined to put out the fire at the end of the story, abandon Wicker and get on with whatever is left of his miserable life. Switching to the story-within-the-story, the narrative takes us to a wretched hamlet called Brood, where the folk are plagued by famine and other miseries. Not the least of these is the bone-dry public house, closed by its proprietor, Mrs. Nelles — pronounced “nails” and played by the divine Veanne Cox — who, disregarding the lovesick pleas of the Vicar (Steve Mellor, looking trapped, but carrying on like the trouper he is), remains in perpetual mourning for her dearly departed daughter, buried these many years in the town boneyard. All of Brood perks up with the sudden appearance of a charismatic saleswoman who is called Anna Livia Spoon but looks suspiciously like the footloose Hetty (and is played by the same less-than-charismatic actress). Miss Spoon is hawking burial bells, a device that allows prematurely buried noncorpses to send a signal alerting their loved ones to exhume them from their coffins. But her real purpose is to trick the bookish lighthouse keeper, Jarl von Hoother (in a deliciously droll turn from T. Ryder Smith), into extinguishing his life-affirming light — and bring this arch tale to an end. Despite its interminable length (135 minutes feels like eternity) and repetitive jokes (enough with the grave-robbing), the text is stylishly written and comically rendered in thick Scottish accents by thesps properly prepped by dialect coach Stephen Gabis. But whatever is genuinely clever about the piece leeches out in production. Taking the play’s downbeat humor entirely too literally, helmer Cullman has mounted the show in monochrome and with no visual dimension to speak of. Dull earth tones prevail, from Anita Yavich’s otherwise worthy costumes (with their actively witty built-ins) to Beowulf Boritt’s brutally austere planked sets. And let’s not even speak of the funereal lighting scheme. A spot of color and a breath of spatial air at the end of the play reveal by contrast how parched the rest of the play is for color. The show’s only textures are those tonal ones that the actors manage to find in the language –an advanced skill at which precious few of them are adept. Cox has the most noticeable success at this trick, dropping her voice to cello level and stroking every word like a musical note. Smith is also completely at home in his lighthouse aerie, surrounded by his books and loving every ludicrous word he comes across. 2-22-06

TheatreMania, Dan Bacalzo – “Stories do what they do,” says the narrator of Glen Berger’s darkly enchanting new play The Wooden Breeks. They often reveal more than is expected and less than one hopes. Set in 19th-century Scotland, the play centers on Tom Bosch (Adam Rothenberg), a poor tinker in a small Scottish town. The love of his life, Hetty Grigs (Ana Reeder), went away on a “brief but unavoidable errand” many years ago with a promise to marry him upon her return. Hetty left behind a newborn son sired by another man. The boy, Wicker Grigs (Jaymie Dornan), lives a miserable existence and is comforted only by Tom’s ever more ludicrous stories of why it’s taking Hetty so long to come home. As the play begins, Tom has grown tired of telling stories; but, at Wicker’s insistence, he agrees to one last tale, which he sets in the fictional village of Brood. The first act of The Wooden Breeks is heavy on exposition, as Berger not only establishes Tom and Wicker’s back story but also introduces the characters who live in Brood. There’s Jarl von Hoother (T. Ryder Smith), a lighthouse keeper who has never set foot in the outside world; Enry Leap (Steve Mellor), the local vicar; Toom the Stoup (Ron Cephas Jones), a graverobbing gravedigger; Mrs. Nelles (Veanne Cox), a woman still lamenting the loss of her daughter many years before; and two young lovers, Tricity Tiara (Maria Dizzia) and Armitage Shanks (Louis Cancelmi). A salesperson also comes to Brood: Anna Livia Spoon (Reeder), who may or may not be Hetty Grigs. She is peddling a device that safeguards against premature burial by outfitting coffins with a bell mechanism that would allow anyone who is accidentally buried alive to call out for help. The setup of the play takes longer than it should, but the second act kicks things into high gear with a number of twists and turns in the plot that are both hilarious and deeply disturbing. As Tom spins his tale, he and Wicker become trapped within it. Their ability to escape is intertwined with the fates of the characters in Brood and the mystery surrounding Anna Livia Spoon. Under the capable direction of Trip Cullman, the ensemble cast helps to make even the drier segments of The Wooden Breeks engaging. Cox, for example, employs a strained, slightly affected manner of speech that seems perfect for her character. Smith makes the obsessive/compulsive lighthouse keeper both pitiful and endearing. Reeder exudes confidence, charm, and an air of mystery, while Rothenberg is an engaging storyteller whose maudlin moments are balanced by his emotional investment in the uncertain outcome of his narrative.

The costumes, by Anita Yavich, are marvelously inventive; they have a period look while often literally reflecting the various characters in the tale. Miss Spoon, for instance, has actual silver spoons stitched onto her bodice, while gravedigger Toom has a shovel on his back. The best costume belongs to Cox’s Mrs. Nelles, whose black dress incorporates portions of a keg; this reflects her standing as the only person in the town of Brood with a license for selling liquor, which she has refused to do ever since her daughter died. Beowulf Boritt’s spare set is dominated by a large, wooden platform that is shifted about. Both Paul Whitaker’s lighting and Fitz Patton’s original music and sound design help to create an eerie atmosphere that supports the tone of the play.

An engaging mystery story, The Wooden Breeks is also a meditation on love, loss, and memory. Berger’s writing is imaginative and often poetic. The playwright has a dark sense of humor that erupts in unexpected places, and a stylistic flair that keeps the play delightfully off-kilter.

Broadway.com, William Stevenson – Glen Berger’s fairy tale-like play boasts a convoluted plot and elements lifted from The Pillowman. It’s not nearly as gripping as Martin McDonagh’s drama, however, and doesn’t hold a candle to Grimm’s Fairy Tales. No, The Wooden Breeks is just plain grim. The rambling, at times incoherent story centers on a Scottish tinker, Tom “Chimney” Bosch (Adam Rothenberg). He falls in love with Hetty Grigs (Ana Reeder), but she leaves him for a sailor. After the sailor in turn dumps her, Hetty returns to Tom. Now she has a child named Wicker (Jaymie Dornan), the bastard son of the sailor. Tom proposes to Hetty, she accepts, and then she departs for a “brief but unavoidable errand.” She never returns, leaving Tom to raise Wicker.

To amuse the boy, Tom tells stories by the fire. He eventually decides to leave Wicker behind, though, and tries to put out the fire (which he claims is the source of his tales). One ember still burns, and Tom uses it to weave a final yarn about a lighthouse keeper, Jarl von Hoother (T. Ryder Smith), in the miserable town of Brood. Making up the bulk of the play, the tale contains eccentric characters but little dramatic action. The longwinded Jarl has stacks of books and never ventures outside. The other townsfolk include a lonely vicar, Enry Leap (Steve Mellor); Mrs. Nelles (Veanne Cox), who mourns her late daughter and won’t reopen the town pub; a gravedigger, Toom the Stoup (Ron Cephas Jones); and a young couple, Armitage Shanks (Louis Cancelmi) and Tricity Tiara (Maria Dizzia), who vow never to marry. Oh, there’s also a saleslady named Anna Livia Spoon (Reeder), who bears an uncanny resemblance to Hetty. Anna sells bells connected by string to coffins in the ground in case someone gets buried alive. (According to the press materials, people really were occasionally buried alive in 19th-century Britain and such bells existed.) And what exactly is a wooden breek, you ask? Well, breek is Scottish slang for britches, and wooden breeks translates as wooden tousers, i.e. a coffin. At one point Wicker turns to the audience and provides this explanation in a speech that feels tacked on. Perhaps director Trip Cullman suggested that Berger should spell out what the heck a breek is. One of the play’s few effective scenes does involve a coffin, but the Pillowman-esque moment is more derivative than shocking. Beowulf Boritt’s set also borrows from McDonagh’s play. As for Paul Whitaker’s dim lighting, let’s just say it’s conducive to napping. The characters’ names are colorful, but Berger doesn’t inject much comedy into his dull, dark fable. As Wicker, young Dornan spends most of the play with his hand stuck in a collection box. (Don’t ask why; in any case, it isn’t funny.) Anita Yavich’s kooky, stylized costumes are similarly perplexing instead of amusing. Cox’s Mrs. Nelles sports a hat that looks like something Mammy from Gone With the Wind would wear–except it has faucets on top. And her dress happens to have a keyhole located near her bellybutton. Cox, whose last off-Broadway outing was the misfire A Mother, A Daughter and a Gun, is stiff and mannered in early scenes but wangles a few laughs later on. Still, the actress (who was wonderful in Company and Alan Ayckbourn’s House and Garden) needs to be more selective about her projects. Rothenberg (best known for playing Streetcar’s Stanley Kowalski at the Kennedy Center) has the largest role and proves to be a fairly engaging narrator. That’s saying something, since his character speaks with a thick Scottish brogue and the story is so tortuous. Dornan makes Wicker likable, though he looks ridiculous carrying around that collection box for two hours. Altogether The Wooden Breeks runs about two hours and 20 minutes, but it feels more like four hours. Needless to say, a good fairy tale shouldn’t feel long and depressing. In the middle of the dreary goings-on, Tom bemoans the fact that he’s “trapped in my own story.” Along with most of the audience, I could relate.

Newsday, Linda Winer – She’s gone, but he loves her to death. For 15 years, playwright Glen Berger has battled the demons of Brood, a place he describes as a “miserable, mythical” Scottish village in the 19th century. Drafts of Berger’s stubbornly odd script about the place have traveled from Alaska and Southern California as he wrote and rewrote, cut and pasted his way eastward to the West Village. Now “The Wooden Breeks” comes to the Lucille Lortel Theatre, where the MCC Theater has staged this Dickens-meets-Brigadoon fantasy-adventure with a big, willing cast and a mordant silly streak that makes us wish we could love the event more than the obsession. This is the sort of theater that needs to be adored to be endured. Director Trip Cullman finds affectionate yet efficient ways to clarify Berger’s seemingly unstageable imaginings of a lovesick tinker named Bosch (Adam Rothenberg), who communes with the woman who abandoned him and her bastard son (Jaymie Dornan) by creating “another interminable chapter of the most torturing choking-noise-of-a-story ever concocted.” There are charming moments in this original folktale, which at its best suggests the haunting metaphysical storytelling of Irish playwright Conor McPherson (“The Weir”). Berger does create a world and people it with unusual types who speak in playful stage-brogue. But the town is not miserable enough to be enchanting. And Bosch’s tale, for all its overwrought weirdness, is not nearly as gleefully torturous as the one promised at the start. By the time Bosch opines that “a story is like a movement of the bowels … it demands you persevere and see it through,” we have lost sight of our sense of wonder altogether. Breeks are britches, a character informs us in the second act; “wooden breek” was the Scottish vernacular for coffin. Fear of being buried alive – daintily called “premature burial” – drives the tale within the fable within the play. We first see our narrator, the tinker, hunched over a fire on a dark stage. He explains his heartbreak in a flashback to Hetty – played with nubile friskiness by Ana Reeder – a wench who vows to marry him after a “brief but unavoidable” errand. Nine years later, Bosch and the kid are still dreaming up stories to excuse whatever kept her from returning.

Hetty is now a mysterious traveling peddler of “bell devices” meant to let the prematurely buried signal distress. The famine-starved townfolk includes an agoraphobic, knowledge-hungry lighthouse keeper (T. Ryder Smith) who makes sense out of the world through encyclopedias and sits on the edge of his lonely sanctuary like a lanky Humpty Dumpty. The ever-surprising Veanne Cox plays the ghoulish widow and proprietor of the shuttered alehouse. The town has lovers who refuse to marry (Louise Cancelmi and Maria Dizzia), a desperate vicar (Steve Mellor) and a grave digger-grave robber (Ron Cephas Jones) who wears a shovel on his back, thanks to Anita Yavich’s witty costume designs. As Bosch tries to snuff the embers of his lost love in his magic campfire, we remind ourselves to appreciate an artist who insists on going his own way. After all, playwright Berger made an episode of the PBS children’s show “Arthur” as an homage to Samuel Beckett. Let’s keep this guy working. 2-22-06

Talkin’ Broadway, Matthew Murray – First things first: The title of The Wooden Breeks, Glen Berger’s new play at the Lucille Lortel Theatre, refers to a coffin. Worried? If that doesn’t scare you away, nothing will: This isn’t another theatrical fright-fest, but one of those plays that presents itself as grim while thinking it’s really about the eternally knowing heart beneath its seamy exterior.

Yes and no. The play’s inspiring message about learning from tragedy and making the decision to move on from it is always on display. But it’s so frequently obscured by the play’s inordinately dark shell that even when that message is at the forefront, you feel as though you’ve been dropped into the waiting room of a stately funeral parlor in Victorian Scotland.

At least that’s where the play is set. But if that doesn’t strike you as an inviting way to spend an afternoon or evening, that’s exactly the problem. Neither Berger nor director Trip Cullman has succeeded at balancing the pervasive gloom of the first half of the story with the increasingly playful turns of the second. If something isn’t part of the exposition (which requires most of Act One), it’s part of the drawn-out denouement (which consumes Act Two).

While The Wooden Breeks is overlong at nearly two and a half hours, there are occasional glimpses of a solid 90-minute play here. Presenting a story-in-a-story, with tinker Tom Bosch (Adam Rothenberg) regaling a young boy named Wicker Grigs (Jaymie Dornan), with the sordid, secret (and entirely fabricated) history of Wicker’s long-departed mother (and Bosch’s one-time lover) Hetty, Berger is fairly successful at examining loss through a jaggedly cracked lens.

In Bosch’s latest tale, the focus is not on Hetty but on the despondent inhabitants of the decript village of Brood: The lighthouse keeper, Jarl von Hoother (T. Ryder Smith), who’s never stepped outside, but devours the science books delivered to his door; young couple Tricity and Armitage (Louis Cancelmi and Maria Dizzia), who won’t marry for fear of ruining their love; the mourning Fanny Nelles (Veanne Cox), recovering from the long-ago death of her daughter and refusing to acknowledge the man who’s long harbored a secret desire for her, vicar Enry Leap (Steve Mellor).

Their doldrums are interrupted by Anna Livia Spoon (Ana Reeder), who’s come to hawk bell devices that allow those buried alive to be rescued before suffocation. Her presence brings with it a tornado of devastating fresh air that upturns all the relationships in the village, at least until she keels over herself. And did I mention she looks exactly like Hetty Grigs?

Sometimes Berger’s inclination toward obviousness works in his favor. He nicely delineates his characters beyond their basic plot functions as representations of Bosch’s inner turmoil and methods of distracting himself and Wicker from their emptiness, and cleverly establishes the many threads of plot that will be woven, undone, tangled, and cut before things are through. But Berger also has a tendency to go too far: He embraces Outer Limits logic to trap Bosch and Wicker in the story until they overcome their grief, and resolves the individual stories in an impossibly tidy way a minute before the show ends.

Otherwise, in look and feel, The Wooden Breeks recalls The Pillowman, the wicked horror-comedy that Martin McDonagh unleashed on Broadway last season. But that was an intensely detailed and layered experience, in which the writing and production fed and fed off of each other; Berger and Cullman, who’s staged the piece with a stiff and stodgy hand, haven’t achieved the same electrifying synthesis.

Berger’s disjointedly whimsical writing seems inseparable from Paul Whitaker’s ethereal lighting and Fitz Patton’s eerily knowing sound design, true, and a number of effects (especially equating Bosch’s fire with the lamp of a lighthouse) do impress. But the style of all this is at odds with Anita Yavich’s horror-movie costumes, and Beowulf Boritt’s generically oppressive set, which could as easily function for a low-budget, high-concept Death of a Salesman as for Berger’s Death of a Saleswoman.

The performances are equally erratic, with Rothenberg giving a miscellaneous Irish/Scottish portrayal, Cox utilizing her usual uptight-detached shtick (though she does it very well), Dornan shrieking his way (if at different volumes) through his role, and Smith convincing all too well as the American nerd (Bosch’s boring alter-ego) trapped in the center of it all. At least Reeder brings a mysterious flair to her roles that helps you understand why both women are so important to so many people.

Mellor brings distinction to his one-note character only in a first-act confrontation with a marauding gravedigger (Ron Cephas Jones) about the graveyard he’s been robbing: “It’s the meeting place of Past and Present – a landscape called Memory,” he says. “Without Memory, we’re half-wits, and with it…we’re connected to our own lives, and the lives of all who have lived.”

But memory, Berger argues, is as likely to isolate as connect. The trick, the play tells us, is learning which memories to keep and which to reject so that life may be as rich as possible. Berger and Cullman might find that an editing process as selective applied to the play as a whole might make this message and others lurking in the shadows more easily face the light of day.

Curtain Up, Elyse Sommer – Unlike the Brigadoonians in Lerner and Loewe’s mythical Scottish village, Glen Berger’s nineteenth century Scotsmen in the village of Brood are an emotionally impoverished lot. Berger’s allegory about how their lives are more like death than the real thing often seems to yearn to be a musical. Instead it is a too drawn out rather dour story within a story. Set in late 19th Century Scotland The Wooden Breeks begins in a hamlet named Clekan-wittit, and moves onto to another named Brood that’s conjured up by a poetic tinker in who’s unable to let go of his love for a woman who left him first for a sailor and then permanently. During the nine years Tom Bosch (Adam Rothenbegr) has spent many a gloomy hour at his tinker’s fire and mooning over his beloved Hetty’s (Ana Reeder) disappearance. He’s displaced his anger by refusing to have much to do with the child (by the sailor) Hetty abandoned when she left on an errand, promising to return before his fire died. Yet he has occasionally regaled young Wicker (Jaymie Dornan) with stories about Hetty in various places and situations which feed the boy’s conviction that his mother will one day return.. As the play opens, Bosch, is determined to leave Clekan-wittit and all its memories once and for all, but his fire in fairy tale fashion resists being doused and he is more or less forced to tell a final story. Into this story which comprises the bulk of the play, the tinker incorporates his determination to snuff out the inextinguishable embers that feed his memories. And so, off he and Wicker go to Brood. Berger’s fairy tale begs descriptive tags like whimsical, wistfully wise and endearingly quaint — and, alas, gloomy and disjointed. Its characters speak with pseudo Scottish brogues but there’s no Scottish mist to obscure its obvious symbolic theme: There’s more to death than burial in a wooden breek (breeks is Scotch for trousers, so that wooden breeks are coffins). Wishful dreams, fear, unrelinquished memories and regrets can lock you into an earthly wooden breek — in short, the living death of a life not fully lived. Like any fairy tale this one needs a fairy, in this case one who will rescue Bosch and the Broodians he’s invented from being buried alive long before they’re due to encounter the Grim Reaper. Mr. Berger’s good fairy is one Anna Livia Spoon who happens to look just like Hetty (no wonder, as she’s again played by Reeder). She shows up in Brood as a saleswoman for a company that sells lights to be placed on top of graves with a cord reaching inside the coffins to enable people inadvertently buried alive to signal for help should they wake up. This plot twist was inspired by a real panic that at one time swept Britain when coffins randomly unearthed were found to contain scratch marks inside the lids– apparently from people mistakenly pronounced dead. Miss Spoon is summoned by Bosch for the specific purpose of helping him to snuff out the flame in the Brood Lighthouse guarded from access by Jarl von Hoother (T. Ryder Smith), a bookish recluse. Spoon’s resemblance to Hetty immediately raises Wicker’s hopes that he’s found his mother at last. The buried in books Lighthouse keeper and the saleswoman who feeds into the villagers’ mounting anxiety about people having been buried alive are of course just part of the Broodian population. There’s Vicar Enry Leap (Steve Mellor) who nurses a secret passion for Mrs. Nelles (Veanne Cox), who has in turn has been nursing her grief over her daughter’s death for years. Since Mrs. Nelles has kept her pub (Brood’s only public house) shut since the her tragic loss, she’s also made Brood Scotland’s driest town. This being a comedy, Mrs. Nelles has filled her own teacup from a whiskey barrel rather than a teapot, thereby diminishing the town’s whiskey reserves all by herself. Other townspeople include Toom the Stoup (Ron Cephas Jones), a Shakespeare like gravedigger and two young lovers, Tricity Tiara (Maria Dizzia) and Armitage Shanks (Louis Cancelmi) who are determined not to let marriage ruin their love. Trip Cullman’s staging creates just the right gloomy aura but neither he or the script move with ease between gloom and whimsy. Beowulff Boritt’s multi-level, movable weathered wood set handily accommodates the segues from the tinker’s compulsive fireside watch in Clekan-wittit to re-enactments of his doomed love affair as well as the events in the town of his imagination. Anita Yavich ‘s costumes are an apt mix of drabness and wit (like the shovel that’s part of Toom the Stoup’s costume).

Adam Rothenberg is appealing as the lovelorn tinker, as is Ana Reeder as both his disappearing sweetheart and Miss Spoon. Veanne Cox, always a marvel of nuanced comedy, is terrific as Mrs. Nelles. You couldn’t wish for a better book-besotted lighthouse keeper than T. Ryder Smith, who starred in Berger’s off-beat Off-Broadway solo hit, Underneath the Lintel (Review). I have no complaints about the rest of the ensemble. If only the author and director could have trimmed all this to a length that could play without an intermission and in the process peel away some of the more tiresome and confusing elements. Ultimately, how you react to this play will depend on your tolerance for offbeat, unabashedly fanciful fairy tales that are way more than a wee bit too long. 2-19-06

nytheatre.com, Martin Denton – I’ve heard it said that whimsical fantasy is just about the hardest thing to pull off in the theatre. Certainly the creative personnel involved with staging Glen Berger’s remarkable play The Wooden Breeks at MCC Theater have done just about everything in their power to negate the pixilated, otherworldly charms of the piece and turn it into a leaden, heavy catastrophe. I was provided a copy of Berger’s script, the perusal of which makes clear that, time and time again, director Trip Cullman ignored or second-guessed his playwright, making a sad shambles of a show that could have been sweet, spry, smart, and lighter than air. Berger’s story is narrated by Tom Bosch, a tinker (for this is more than a hundred years ago) in Scotland. Years before, Tom fell in love with Hetty Grigs, but she turned him down to run away with a sailor, who in turn abandoned her but left her with a little boy. So Tom again asked Hetty to marry him, and this time she accepted the proposal—”As soon as I return from a brief but unavoidable errand out of town.” Hetty handed Tom her baby, called Wicker, and disappeared. Now—as our play begins—Tom is stuck minding 9-year-old Wicker on the outskirts of a town and on the outskirts of life. Both are waiting for Hetty to come back, even though at least one of them is reasonably certain she never will. Tom bides the time and provides a kind of comfort to Wicker and himself by spinning tales in front of the fire, tales purporting to explain where Hetty has gone and why she’s not returned. What follows—the play proper, for this has all been prologue—is a long and elaborate concoction, the last of Tom’s tales about Hetty, about a town called Brood and its eccentric inhabitants, especially a lighthouse keeper named Jarl von Hoother who has lived indoors all his life with mountains of books codifying the world he’s never seen first-hand. The lighthouse contains a beacon fueled by a meager amount of oil; eventually Jarl comes to realize that if he’s ever to get out, he’ll need to use that oil, thus putting the light out. Some of The Wooden Breeks—a good deal of it, actually—revolves around how to make that choice, and its consequences. Elsewhere in Brood are a vicar who is wooing a melancholy lady named Mrs. Nelles; she lost her daughter a long time ago and ever since has refused to re-open her place of business, the town’s only public house, thus denying her fellow citizens of much-wanted spirits. There’s also a pair of lovebirds, romantic young Tricity Tiara and her handsome beau Armitage Shanks. Young Wicker is in the story, too; and darned if Hetty doesn’t materialize as well, in the guise of traveling saleslady Anna Livia Spoon, purveyor of a singular and ingenious device, a bell to be installed at gravesites (with the pull-cord running down into the coffin), to provide a means for folks unfortunately buried alive to attract the attention of the living. Tom keeps figuring in the story, also; or at least his own story keeps blending into his made-up one. Tom asks: “What’s been known to visit a man unexpectedly, then worm its way through every defense til it collars the heart? What spellbinding force exists in Creation that can make a man do things he wouldn’t imagine doing in a million years?” It takes him the entire length of his increasingly complicated and unyielding tale to learn the answer for himself; and the direction that points him at The Wooden Breeks’ conclusion is not where you think. Berger’s play is as canny and precise a puzzle as his earlier Underneath the Lintel, and every bit as wise. But you wouldn’t know it from MCC’s production. The heart and joy at the center of this piece have been sucked out rather systematically: Paul Whitaker’s lighting design ranges from dim to dark to very dark with almost no relief; Beowulf Boritt’s set is a wooden monolith bearing no relation to lighthouse or other dwelling but meant to serve as both simultaneously; and Anita Yavich’s costumes, jarringly, look like designs for some mannerist/horror-show version of Disney’s Beauty and the Beast, with vestigial representaions of each character’s occupation grafted on their clothes (Mrs Nelles has a keg built into her bustle and taps in her hat; Armitage, oddly, has a chair back attached to his suit jacket). The actors try to bring life to the piece, notably Adam Rothenberg (a very sympathetic Tom), Veanne Cox (humorous as the wry, dry Mrs. Nelles), Steve Mellor (as the pragmatic vicar), and the invaluable T. Ryder Smith (as poor lonesome Jarl van Hoother). But Trip Cullman’s direction traps them in a wrongheadedly heavy interpretation of the play, and this despite Berger’s own urging, in the script, to remember that “‘to brood’ means not only ‘to mull darkly over events long past’ but also ‘to await for new life to hatch’.” Breeks, by the way, is a Scottish word for trousers; wooden breeks, young Wicker Grigs informs us, means a coffin. Berger’s beautiful play is all about climbing out of the wooden breeks we sometimes dig ourselves into; but the sad fact is that this MCC production is all hole, with no sign of light anywhere. I hope this is not the last New York sees of this singular work; that would be a terrible waste. For now, though, only a hint of the life-affirming wisdom contained in The Wooden Breeks can be gleaned at the Lucille Lortel Theatre. 2-18-06

Backstage, Karl Levett – Glen Berger is clearly a playwright of imagination. Unhappily, in The Wooden Breeks, this ambitious imagination seems to be on overload. This folksy tale is a story-within-a-story laden down with mystical metaphor, magic, philosophical leanings, and eccentrically cute characters — layers that obscure rather than enrich the play. With a late-19th-century setting, the play begins in Scotland and moves to a mythical village, with Berger employing the historical fact of the bell device. This was an invention that sat on top of a grave with a cord leading into the coffin to prevent its occupant from being accidentally buried alive — a genuine fear at a time when people were pronounced dead who were merely comatose. Onto this intriguing premise Berger has piled additional ideas and conceits until the plot is burdened down to a crawling pace. Whatever this story may be, nimble it is not; it’s an involved narrative that is oddly uninvolving. The fireside telling of the story is by tinker-turned-poet Tom “Chimney” Bosch (Adam Rothenberg) to 9-year-old Wicker Grigs (Jaymie Dornan), who becomes a Dickensian orphan in the new story set in the hamlet of Brood, a place crammed with colorful characters. There’s Jarl von Hoother (T. Ryder Smith), a lighthouse keeper who has never left his lighthouse; Mrs. Nelles (Veanne Cox), the public-house proprietress who has closed shop; Enry Leap (Steve Mellor), the vicar in love with Mrs. Nelles; Toom the Stoup (Ron Cephas Jones), a grave-robbing gravedigger; and a pair of lovers, laundry maid Tricity Tiara (Maria Dizzia) and her swain, Armitage Shanks (Louis Cancelmi). Enter Anna Livia Spoon (Ana Reeder) to peddle her bell devices and affect lives. And that’s just the beginning…. While director Trip Cullman has given the play first-class production values, he’s unable to bring this turgid tale to life. Beowulf Boritt’s stark set is a virtue, while Anita Yavich’s clever costumes add a layer of expressionism to the pile. Among the hard-working cast, not even the estimable Cox can lighten the overstuffed proceedings. 2-22-06

Village Voice, Alexis Soloski – Fancy Pants: Berger’s latest play is buried alive in its own whimsy. Whatever, we ask, are these “wooden breeks” that lend Glen Berger’s latest play its name? Well, according to nine-year-old Wicker Grigs, “Breeks are trousers. The wooden breeks are wooden trousers. That is a coffin.” Out of the mouths of babes and sucklings! Wicker, why weren’t you always onstage? Berger’s tortuous piece of fancy packs in so many frames, asides, and puns that further annotations would have been most helpful. As the play opens, tinker Tom (Adam Rothenberg) grudgingly prepares to tell Wicker (Jaymie Dornan) a tale. For the past nine years, since the abrupt disappearance of the boy’s mother (and Tom’s sweetheart) Hetty, Tom has nightly conjured Hetty by spinning stories explaining her continued absence: She’s delayed by pirates one week, influenza the next. In this final legend, Hetty arrives at the “miserable, mythical Village of Brood” in the guise of coffin-device saleswoman Anna Livia Spoon. If the setting and character names haven’t already suggested it, we are inextricably in the land of whimsy—albeit of a murky sort—and stuck for well over two hours there. While Berger is incredibly (perhaps infuriatingly) talented in his use of language, he doesn’t possess the same skill at narrative motion or dramatic arc. Lines such as “a keepsake to keep in your keep” and “his life is a study in study and tea” drag the action down like so many trenches of tar. Director Trip Cullman has assembled a lovely cast—Rothenberg’s tinker, T. Ryder Smith’s lighthouse keeper, and Veanne Cox’s anhedonic tapstress do illumine the proceedings. But when the tinker’s firelight is at last extinguished, we aren’t eager for a rekindling. 3-7-06

cityspecific blog, Jeremy – As a child, I remember being both horrified and captivated by the idea of a certain invention to guard against premature burial. Above ground, it was a bell on a pole connected to a wire. Below ground, the wire was inserted into a recently interred coffin. The idea being that if someone were actually still alive, they could tug on the wire from inside the coffin, ring the bell, and alert the gravediggers not to start laying any headstones just yet — that is, of course, if the victim didn’t die of fright immediately after realizing they’ve been buried alive. All very creepy stuff, although I guess the fear of being buried alive is something that’s haunted us for ages and why not use some of that Industrial Revolution ingenuity to solve the problem, right? Without doing any additional web searches at this late hour, I don’t know whether a) this device was ever actually made, b) it was ever actually used, or c) the bell ever rang because someone was tugging on it from six feet under. But that seems hardly the point, for — real or imagined — the bell device is a powerful metaphor for the feeling of isolation in life and the need to communicate and connect with others. It stands at the center of a Dickensian play running at the Lucille Lortel Theatre called The Wooden Breeks. (Breeks, I’ve learned, is old Scottish slang for breeches or pants, and while I don’t remember it being spoken in the play itself, you can see how the phrase might be a euphemism for a coffin.) The play takes place during the latter part of the 19th century, first in a “real” Scottish town and then, for most of the remainder, in an imagined (still Scottish) town dubbed Brood. The play is told by a storyteller with the equally evocative name Bosch (Hieronymus, anyone?) who loved a woman who left him for a “brief but unavoidable errand” just after she agreed to marry him, never to return, leaving behind her son by another man. The storyteller begrudgingly spins Odyssean yarns to the boy about where his mother might’ve run off to, and the bulk of the play consists of one such “chapter” in which the man and the boy actually step into the frame of the tale — literally, thanks to the stage design. This world of Brood is populated by a Gothic collection of characters: A man who’s locked himself in a tower, content to learn of the outside world only from a collection of reference books deposited through his mailslot. A former pub mistress, played with charming pallor by Veanne Cox, who’s still wearing widow’s weeds nine years after the death of her daughter and won’t open up the public house for the townspeople to drink. (Two people whom one might call “buried alive.”) Also: A spindly gravedigger. A world-weary preacher. A painter and a laundress — a pair of lovers, Romantic in the capital-R, Berlioz sense as much as the modern one. Their costumes, too, are definitely worth noting: Most of them have implements of their trade literally attached to their outfits. A small shovel on the gravedigger’s back, pages of manuscript woven into the preacher-cum-town-historian’s cloak, the back of a chair — for sittings, perhaps — on the painter’s back, a washboard positioned like a bodice on the laundress, and spigots on the bar matron’s hat. Into this poor and bleak town comes a saleswoman named Ms. Spoon who gently warns the people about premature burial and hawks the aforementioned bell device in the process. Besides the seduction of the sale, she also inadvertently woos some of the men in town. This woman is played by the same actress who was the storyteller’s missing fiancee, and Bosch and the boy are forever debating whether this character in the story they’ve invented is actually the one’s lover and the other’s mother. The line between how much power each has over what’s real and what’s imagined seems intentionally blurry. While much brooding about lost loves and missed opportunities and distances left uncrossed fills the play, it’s also packed with a healthy bit of plot that I don’t think I’d be able to retrace here. It took a while to get into the action, but after a while, it really started to pay off with some dazzling moments that play with the idea of reaching out, ringing our bells, worrying that no one is out there to hear them. (Kind of like the web at times, right?) The acting may hew a little too close to caricature, but the writing manages to keep the characters complex and human. Since so much happens during the course of two and a half hours, I was left wondering if a repeat viewing would reveal a work that’s richer or poorer than at first. Is all the hurrying around stage to distract us from the spareness of it all or would more become clear the second time around? I don’t know, but it’s nice to see a play that prompts that question in the first place. I certainly felt throughout the performance like the themes were rich and thought provoking. I just wonder whether it would’ve been better to have experienced them more in my heart than in my head. Those criticisms aside, I’d definitely recommend the play, which officially opens Tuesday. The playwright is Glen Berger and the director is Trip Cullman, who also did Dog Meets God and Swimming in the Shallows recently. (Seeing this play has made me excited to see the next installment of PBS’s Bleak House miniseries this Sunday.) 2.17.06

NY Sun, Helen Shaw – Amid the postmodern enthusiasm for deconstruction, old-fashioned storytelling onstage seemed passe. But now that we’re post-postmodern, playwrights have gotten excited about narrative again. Unfortunately, their enthusiasm tends to outpace their structures, and hearing about a “story” seems to stand in for actually enjoying one. In Glen Berger’s “The Wooden Breeks,” now at the Lucille Lortel, a self-conscious attempt at glorifying the storytelling tradition totters under the weight of its own construction.Mr.Berger has the first component necessary for a good yarn: imagination. But after a solid hour of breathlessly introducing his quirky characters, the lack of the second element – an organically developing plot – comes hurtling to the fore.

Mr. Berger’s framing device and narrator is Tom Bosch (Adam Rothenberg), a cynical tinker carrying a torch for a runaway lover, Hetty (Ana Reeder). When Hetty left him, she also left behind her son by another man – and it falls to Tom to entertain him.Tom pours all his bitterness into telling a nasty story about a fantastical town called Brood where everyone is starving, shut in, or sorely disappointed by love. Even the town lovers refuse to marry, since marriage would extinguish their passion forever. Brood does a brisk business in grave digging, and many of the townspeople are afraid of being buried alive. Capitalizing on this fear, a saleswoman (also Ms. Reeder) swings into town and seduces most of the men, including Jarl van Hoother (T. Ryder Smith), the reclusive lighthouse keeper. Her product is a little bell that sits on top of burial plots and drives people crazy. Tom soon loses himself in the story, and discovers he’ll have to finish it to find his way out again. But Brood, with its many coffins and lockboxes and padlocked lighthouses, is a very hard place to escape. More than 2 1/2 hours long,”The Wooden Breeks” should have more than enough time to tie up its loose ends and deliver its plot ingredients on time. Instead it jerks along in long lulls and sudden rushes of exposition, which do much to disrupt the play’s real moments of emotional insight. This is a rough ride, to be sure, but it could have been far smoother in a different production. Mr. Berger, even when he’s leapfrogging over certain key scenes (and telling us about them later), does have a pen for texture. On the page, he describes a rich and fantastical world, cozy and cluttered with Grimm-era touches; his stage directions drum up marvelously rich images (he even calls for peat so the stage will smell right).

But director Trip Cullman approaches Mr. Berger’s light and whimsy touches with a hammer and tongs; his stolid direction and mismatched design scheme leaches out much of Mr. Berger’s dark caprice. Of the design team, only costume designer Anita Yavich responds to the call: Mrs. Nelles, the town tapstress, has taps all over her hair, and von Hoother has tiny boxes built into his clothing to display his butterfly collection. On Beowulf Boritt’s bleak, raw-wood set, however, they look as out of place as Dr. Seuss characters behind bars. Many of the actors seem a bit at sea, hovering between the stylization called for by the script and duller reality. Mr. Rothenberg responds to the tension by yelling his lines; Ms. Reeder whines; and the usually brilliant Mr. Smith delivers a twee caricature, only rarely letting us see his electric intensity. Veanne Cox as Mrs. Nelles manages to earn huge laughs by simply blowing on her tea. Her plummy, hooting delivery offers a glimpse into how jolly “Breeks” could have been, had Mr. Cullman taken the whole thing a bit more lightly. 2.22.06

kilobyte blog – Yesterday I has the opportunity to see MCC Theatre’s latest, The Wooden Breeks, courtesy of the marketing director, Shanta Mali. The Wooden Breeks is the story of a man, Chimney Bosch and a boy, Wicker Grigs, abandoned by the same woman. (The man’s lover/fiancée, the boy’s mother) To stave off the reality of their abandonment, the man tells the boy stories of his mother’s exploits, what is keeping her away, a la Scheherazade. The Wooden Breeks is the last story.

The Wooden Breeks production combines the hyper-poetic style of Under Milkwood with the gothic storybook-gone-wrong aesthetic of Shockheaded Peter. The production is a distinctly Irish, whiskey-induced tall tale, complete with properly one-note characters, simple sets and props, embellished costumes and a pair of unlikely heroes who work against all odds to attain their freedom.

The playing space at the Lucille Lortel Theatre was turned into a simple platform set with the outlines of a room. As the narrator made up the story, the characters used what was around them to adapt. Benches are stood on end to make doors, a hand gesture causes a foghorn to sound, etc. The visual expression came through in the costume design. Each character had a name, an occupation and a corresponding costume. For example: Ms. Tricity Tiara, the wash maiden: her skirt was sweeping and romantic and made entirely of hanging socks! Toom the Stoup, the Gravedigger’s jacket had a shovel built right into the back, the curve of the handle forcing a curve in his posture. The costumer designer, Anita Yavich, deserves full credit this award season.

The talented Adam Rothenberg (Danny and the Deep Blue Sea) narrated the story as Mr. Bosch with excellent momentum, keeping with him the truth that he was spinning a yarn, even chuckling at his own jokes. (Including my favorite, “Come back from the dead!? Bloody easy if your name is Christ.)

Other cast highlights included Veanne Cox (Last Easter) as the rigid-backed Mrs. Nelles and T. Ryder Smith (Thom Pain) as Jarl von Hoother, the reclusive lighthouse keeper. Ms. Cox was unwavering in her portrayal of a grieving mother, thoroughly dour and humorless, even as the audience laughed. Mr. Smith, the unknowing fulcrum, had the most poetic language to handle and did it with impeccable rhythm and diction. Edith Skinner would have been proud.

The style of the playwriting reminded me of the film Big Fish. There were two plots running, Mr. Bosch and Wicker’s salvation and the tale he was spinning. The two plots were interconnected, and like Big Fish, while the audience never loses sight of the “true plot,” the line between reality and fiction is blurred and crossed. Both stories were interesting enough on their own, but woven into one were truly compelling.

I recommend this production and would note that it’s a good choice for kids.

Note: “Breeks” are trousers, the wooden trousers, and refers to a coffin.

Columbia Spectator, Rachel Ely – A Puzzling Story Buries Itself. Buried alive, that is the dark, literal and allegorical theme of Glen Berger’s play, The Wooden Breeks (period slang for coffins), now playing through March 11 at the Lucille Lortel Theater. The play begins on the roadside of a small 19th century Scottish town where the faint glow of a fire and a poor storyteller are your only guides in the darkness. Our storyteller, Tom “Chimney” Bosch, has given up hope that his lost love, Hetty Grigs, will ever return to him. She left behind her orphan son, Wicker, who wants nothing more than to hear stories of his mother. On this particular night, Bosch tells a story of the mythical Village of Brood whose inhabitants are, in one way or another, stuck. Enry Leap, the vicar, loves history and cannot give up the past; Mrs. Nelles stays forever in mourning over her daughter’s death; and Jarl von Hoover, the lighthouse keeper, hides from the outside world. And all have recently become obsessed with the notion of being buried alive as a result of a bell device being sold by a peddler named Anna Spoon. This bell device can be attached to the finger of the decreased as a way to alert citizens of their existence. And just as these characters are trapped in their lives, Bosch finds himself trapped in his own story and must find a way out of Brood. Berger explores the nature of storytelling by causing his narrator to lose control of his own story and become a member of the audience. Though Trip Cullman (director of Dog Sees God) does not actually make Bosch sit in a seat with the audience, his staging still perpetuates this idea. He begins the play with Bosch waiting on stage for the story to start just as the audience waits in their seats. Cullman also has Bosch bring a second stage forward thereby providing a separate setting for his tale within a tale. And he tops it off by having suspended moments in which Bosch says nothing and merely observes his story with his back to the audience. However, Berger and Cullman spend so much time trying to propagate this idea of storyteller and observer that they often forget to just tell the story. Though the plot has its moments of intrigue and mystery, the play often becomes too cryptic. It begins to feel like a puzzle rather than a story, and it is a puzzle with too many missing pieces. Essential scenes in the play are rushed and leave the audience longing for a rewind button. And rather than following the story you might find yourself trying to determine the significance of the character’s costumes: I suppose it makes a little sense that the laundry girl, Tricity Tiara, has a dress made out of socks and a corset in the form of a washboard, but there seems to be no reason why the character Armitage Shanks has the back of a chair attached to him all though the first act.

But where the story may be lacking, the caliber of acting talent certainly isn’t. Adam Rothenberg plays Bosch with a sardonic verve recalling the crafty pickpocket, Fagin in Oliver. And Veanne Cox’s deadpan delivery as Mrs. Nelles provides the comic relief in the play, and when she is paired with Steve Mellor’s comically melodramatic portrayal of Enry Lead, the show truly comes to life. But the man who steals the show is T. Ryder Smith who plays Jarl von Hoover with intensity and a feigned insanity that leaves the audience waiting in anticipation for his next monologue. But even the actors cannot change the fact that the play caps off at about three hours in length and can feel exhausting. And let’s just hope that it doesn’t bury you along with the characters trapped on stage. 3.1.06

[previous] [next]