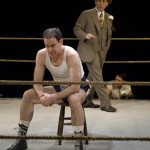

Photos by Craig Schwartz

Above, from top: Dion Graham, Katie Barrett, Rufus Collins, Al White, T. Ryder Smith; Dion Graham, David Deblinger, T. Ryder Smith; T. Ryder Smith, Dion Graham; Dion Graham, Al White, T. Ryder Smith; Al White, Dion Graham, David Deblinger, T. Ryder Smith, John Keabler; T. Ryder Smith, Dion Graham, Rufus Collins; Katie Barrett, John Keabler, T. Ryder Smith, David Deblinger; Rufus Collins, David Deblinger, John Keabler; Al White, Dion Graham; Katie Barrett, Rufus Collins, T. Ryder Smith; T. Ryder Smith; Dion Graham, Rufus Collins, T. Ryder Smith; T. Ryder Smith.

Excerpts from the reviews

Full reviews are below

” . . . sets out to restore the rep of Joe Louis (1914-81), unassuming “Brown Bomber” sandwiched between the more controversial Jack Johnson and Muhammad Ali but arguably the one who holds the strongest claim to the title of greatest ever. If rehab effort succeeds, it seldom rises above the level of an A&E “Biography” segment due to cipher protagonist and thematic uncertainty. Pulled punches prevent a knockout, but as sheer entertainment . . . colorful Old Globe world preem wins a decision on points. . . . Characters prowl (and commentators orate) across, around and beneath Lee Savage’s superbly crummy boxing ring set, with considerable variety and several visual coups to command attention. Tyler Micoleau’s lights imaginatively distinguish Louis’ public and private worlds, and though movies have spoiled us, Steve Rankin infuses the snatches of pugilism with as much realism as the stage permits. Still, the most effective boxing sequence is the second Louis-Schmeling bout, which aud and actors experience exactly the way America did: staring at a radio lit from above at center stage, everything else hushed in the dark. Among the capable ensemble, T. Ryder Smith adds a welcome touch of film noir in his uncanny resemblance to the late, great Marc Lawrence. He’s got the best handle on the alliterative sportswriter patois Drukman pours over everything like gravy and scores with a ref’s sizzling monologue . . .” Bob Verini, Variety

“Gritty . . . Fascinating but imperfect . . . Drukman’s script is filled with an embarrassment of riches; perhaps his subplots need to be winnowed to give the evening more focus. . . . The five supporting players provide a gallery of characters, many of them 1930s archetypes. Deblinger’s sports columnist, spouting creatively racist nicknames for Louis, seems pulled from “The Front Page.” Katie Barrett shows amazing range as a torch singer, a nurse, a starchy FDR factotum and a reporter who carries on a clandestine affair with Louis. T. Ryder Smith does a bang-on imitation of a breathless Golden Age boxing announcer and steals the show with a profane paean to the ring’s referee. (I’m not sure what to make, though, of his homoerotic Hitler.) . . . ” Paul Hodgins, Orange County Register

Video

Full reviews

Variety, Bob Verini – With “In This Corner,” Steven Drukman sets out to restore the rep of Joe Louis (1914-81), unassuming “Brown Bomber” sandwiched between the more controversial Jack Johnson and Muhammad Ali but arguably the one who holds the strongest claim to the title of greatest ever. If rehab effort succeeds, it seldom rises above the level of an A&E “Biography” segment due to cipher protagonist and thematic uncertainty. Pulled punches prevent a knockout, but as sheer entertainment Ethan McSweeny’s colorful Old Globe world preem wins a decision on points. Transitional figure Louis (Dion Graham) was carefully schooled to restrain any Jack Johnson-like antics likely to turn off the majority culture. (For a time, he was forbidden white opponents on the same grounds.) American-hero status came through celebrated battles with Nazi Germany’s pride and joy Max Schmeling (Rufus Collins) and subsequent Army induction, but postwar tax problems, drug abuse and commitment to a psych ward haunted him into decline and obscurity. Who was that man in that corner, and why did he fall so far so fast? Drukman lays out all the key events, punctuated with ironic commentary from a small but energetic chorus of onlookers and participants, but no consistent, coherent point of view ever emerges. Whether Louis was a tool, victim or wise player in the effort to control his emotions for white America’s benefit isn’t explored. Nor can we extrapolate much from his impassivity at the race prejudice encountered at every phase. Hints of inherited mental problems are raised, doubted, dropped. Graham’s dignified, world-weary Joe hints at more than meets the eye, but in a way that’s the problem, as the writing never provides enough to sink our teeth into. “I am a man; I have my name” is about as deep as the investigation ever gets. Why did America drop him? Why was he forced into wrestling matches wearing an Indian headdress? Wherefore the appeal of heroin? Throughout, Louis garners our sympathy but rarely our understanding. Schmeling’s treatment is even more ambivalent, his involvement in Hitler’s world propaganda plans papered over in a shockingly insensitive (and opportunity-wasting) sequence with a burlesque Hitler, denying the boxer’s dilemma any reality or tension. Thereafter, he’s one-dimensionally noble, his main characteristic a Col. Klink accent more appropriate to a Bob Hope wartime farce. The Hitler scene is McSweeny’s only major flub, as he otherwise satisfyingly applies fancy footwork to disguise material’s thinness. Characters prowl (and commentators orate) across, around and beneath Lee Savage’s superbly crummy boxing ring set, with considerable variety and several visual coups to command attention. Tyler Micoleau’s lights imaginatively distinguish Louis’ public and private worlds, and though movies have spoiled us, Steve Rankin infuses the snatches of pugilism with as much realism as the stage permits. Still, the most effective boxing sequence is the second Louis-Schmeling bout, which aud and actors experience exactly the way America did: staring at a radio lit from above at center stage, everything else hushed in the dark. Among the capable ensemble, T. Ryder Smith adds a welcome touch of film noir in his uncanny resemblance to the late, great Marc Lawrence. He’s got the best handle on the alliterative sportswriter patois Drukman pours over everything like gravy and scores with a ref’s sizzling monologue defending his role in raising a prizefight above the level of “Boy meets boy, boy hits boy, boy sends boy into coma.” “I make the KO … OK,” he insists. Aficionados of fistiana and/or beefcake should show up early for John Keabler’s solo warmup routine establishing a suitably sweaty mood. Thesp’s skills with a punching bag, medicine ball and (especially) jump rope are far more impressive than those of the canvas-munching palookas — Primo Carnera, Max Baer and various Louis sparring partners — he impersonates during the show proper. 1.13.08

Los Angeles Times, Charles McNulty – ‘In This Corner’ packs a punch. A lively drama charting the rise and fall of boxing champ Joe Louis scores more hits than misses in its boxing-ring setting at San Diego’s Old Globe. Boxing has long served as a metaphor for theater. Bertolt Brecht, the grand innovator of 20th century political drama, envisioned spectators sitting around the stage puffing on cigars as they watched characters attempting to knock each other out with contrasting viewpoints. “In This Corner” — Steven Drukman’s play about the great heavyweight champion Joe Louis, premiering here at the Old Globe — follows Brecht’s lead and literally transforms the stage into a boxing ring. The result is a swinging if not entirely walloping way to start the theater’s new regime, led by CEO/Executive Producer Louis G. Spisto, now that Jack O’Brien has assumed the title of artistic director emeritus. In telling the epic tale of Louis’ heroic rise and sputtering post-retirement fall, the playwright throws jab after jab of sociopolitical interpretation. We learn about Louis’ origins in the red clay mountains of Alabama, the racial obstacles he encountered throughout his career even after his victories transformed him into a rousing national symbol, and his middle-aged descent into drugs, debt and mental illness. But the drama, which shifts back and forth in a span that runs from 1930 to 1970, never scores an emotional knockout. And unfortunately, Louis the man remains little more than a heavily annotated Wikipedia entry. Still, the production, kinetically directed by Ethan McSweeny, keeps the intellectual bob-and-weave lively. A prizefight atmosphere dominates even when the only thing happening is an expository swirl of reporters, managers, announcers and trainers. Drukman may not have anything revelatory to say, but he treats the slangy speech of each character as though it were part of a hip-hop poetry slam. This can grow tedious at times. But McSweeny ingeniously converts the old-school word-spinning into modern-day theatrical rhythm. At the center of the story are the bouts between Louis (Dion Graham) and his formidable German opponent, Max Schmeling (Rufus Collins), who had the misfortune of being a star athlete during the Nazi era. The Third Reich had a vested interest in Schmeling’s success. Aryan superiority was on the line. Drukman spells the point out by having Hitler (T. Ryder Smith, in one of his many roles) make a cameo in which he menacingly advises Schmeling to be a good son of the Fatherland. Of course, Louis understood as well as anyone the crushing weight of race. Nicknamed “the Brown Bomber,” he was always bumping up against bigotry and its burdensome reverse — a desire to see him as a transcendent example.The play introduces Louis as a shy young man with a bad stammer who wants to please his mother and lead a peaceful life as a musician. A team of boxing king-makers, however, decides he’s the next champ. Before they even lay eyes on his hulking frame, the members of this group are determined to manufacture a new pugilist prince. And why not, since they have all the bases covered? There’s a sportswriter to supply the buzzwords and hype, an announcer to rev up the crowds and a trainer to teach all the necessary moves. The only thing missing is a “great villain to come along and oppose him,” and the Nazis take care of that by allowing Schmeling to fight abroad. Though reluctant at first, Louis turns out to be easy to mold. He’s repeatedly warned by his no-nonsense trainer, Blackburn (a solid Al White), to follow a number of rules. He shouldn’t speak in public, he shouldn’t have his picture taken with a white woman, he should never go into a nightclub alone, and he should never gloat over a fallen white opponent if he wants whites to keep attending his fights. These were mistakes that Louis’ openly contemptuous predecessor Jack Johnson made, and Blackburn vows that “the last smile is gonna be ours.” Most important, he reminds Louis of his ABC mantra: “Always Be Clean.” This becomes increasingly hard as the years go by and the boxer’s dwindling celebrity proves a weak analgesic for the pain of a life whose only true freedom was in the ring. Not surprisingly, the man who understands Louis’ plight best isn’t his psychiatrist but Schmeling, who has flourished as a businessman in Hamburg after the war. Though their fates diverge widely, their histories intersect in crucial ways that extend beyond laying each other flat.

Graham and Collins are effective as the main combatants, but their roles have all the internal specificity of animated figures. Instead of nuance, Drukman bestows on them Significant Cultural Meaning, which would be fine if it were more organically earned.

From the beginning, Graham emphasizes the heavy tread of Louis’ embattled spirit. There’s not much development in the characterization as written, and the performance mostly highlights the various notes of sadness. Still, the poignancy is genuine if a little static. Collins, whose German accent seems as ostentatious as the fur coat he wears when he sweeps into Louis’ psych ward as an older man, certainly makes a vivid stand-in for Schmeling. But like Graham, all he can do is zero in on the softer aspects of his broadly conceived part. The supporting cast has zestier material to work with. In darting from character to character, Smith, David Deblinger and especially Katie Barrett are allowed to gallop away with most of the fun, turning “shinola into Champagne,” to borrow period vernacular from one of the reporters in the play. The production design, dominated by Lee Savage’s boxing ring set, is crackling good across the board. Tyler Micoleau’s lighting helps create the excitement of a much-anticipated brawl, as does Lindsay Jones’ sound design, which cleverly layers radio play-by-play with booming microphone commentary. McSweeny’s direction finds the energetic soul of Drukman’s drama, which may not be one for the ages but definitely provides a brisk theatrical workout for actors and audience alike. 1.16.08

San Diego Union-Tribune, James Hebert – Period feel as you are there, ringside. Besides battling his archrival Max Schmeling, Joe Louis flattens enough bums in the course of “In This Corner” that for a time the show is a regular palooka-palooza.

The production’s own fight card is a little mixed, too. It makes great use of the Old Globe’s Cassius Carter stage, planting a boxing ring smack in the middle of the arena-style theater, where Steven Drukman’s inventive play is having its world premiere. It’s also bathed in a rich period feel, from the vintage typewriters clacking away at ringside to the smoke floating high above the canvas to the language of the assorted ring rats, all wisecracks and wry rhymes. About that language, though: Drukman clearly is having fun with the overripe stylings that distinguished the boxing talk of the time – that time being (chiefly) the 1930s, the great Louis’ heyday. At its best, the dialogue bobs and weaves like a kind of pug’s poetry. Even so, the purposely purple prose (hmmm … maybe contagious?) is carried so far that the play starts to feel a little punch-drunk on the stuff. It’s funny early on when the lunkheaded but ambitious reporter (David Deblinger) and seen-it-all boxing honcho (T. Ryder Smith) are brainstorming absurd nicknames for Louis (“The Chocolate Chopper,” say, or “The Mocha Mauler”). But by the time Smith cuts off more such patter at the start of Act 2, lamenting that “For the love of Pete, they have a limit!,” you might be thinking said barrier was passed a few rounds back. “In This Corner” revolves around the two heavyweight bouts Louis fought against the German champ Schmeling in 1936 and 1938. The Brown Bomber (not much of an improvement on those fanciful nicknames, but it stuck) lost the first fight in 12 rounds.

He won the second in barely two minutes – a left hook to Hitler and his “master race” blather. But like Jesse Owens’ triumph at the Berlin Olympics two years earlier, Louis’ couldn’t trump the color of his skin in a segregated United States. Drukman and the play’s director, Ethan McSweeny, introduce a tricky time-travel gambit, flashing forward to a 1970 meeting between Louis and Schmeling in a psych ward. They manage it deftly; the interludes could have been intrusive but instead illuminate the two fighters’ odd bond. As Louis, Dion Graham might not be quite so light on his feet as you’d imagine the Bomber to be (tall order, that), but he amply conveys the beleaguered champ’s mix of resolve and resignation. Rufus Collins also proves a good match as the proud but sympathetic Schmeling. Considering the multiple roles the other cast members take on, the acting earns wows all around. Katie Barrett gets laughs as a tough-broad reporter and jaded nurse; Smith and Deblinger juice things up as hustlers, hacks and (in Smith’s case) even Hitler. Al White is ideal in a pivotal role as Louis’ trainer and confidant. And the athletic John Keabler not only serves as a sparring partner and procession of stooges for Louis, but also puts on a phenomenal jump-roping show before the show starts. (It’s not often a play has an undercard.)

Once the self-conscious clamor of Act 1 fades, the play’s latter half rewards with scenes that lay bare the wars raging inside Louis’ own heart. In those moments, the regrets and frustrations of a misunderstood hero hit like a fist. 11.12.08

Orange County Register, Paul Hodgins – A gritty, ambitious new play about boxer Joe Louis marks a new era at the venerable regional theater. “In This Corner,” Steven Drukman’s fascinating if imperfect new play about boxing legend Joe Louis, is the first solid indication of what the Jerry Patch era at the Old Globe will look like.

Patch, a longtime talent spotter at South Coast Repertory who helped it gain a national reputation for developing new plays and playwrights, left a couple of years back for San Diego’s venerable company. Since December, he and Shakespeare Festival director Darko Tresnjak have been co-artistic directors of the Globe, one of America’s largest regional theaters. If Friday’s world premiere of “In This Corner” is a harbinger of things to come, the Globe is about to get a lot livelier. Previous artistic director Jack O’Brien focused (and made his Broadway reputation) largely on mainstream musicals and big-name playwrights. Patch has long been a champion of daring and innovative spoken-word drama by fresh new voices, and this is the theater’s first commissioned world premiere under his stewardship. While it won’t ruffle too many of the snowy heads in the Old Globe’s subscription audience, “In This Corner” bears many of the hallmarks of Patch Theater. It’s thematically ambitious, engrossing, and revels grandly in the high and low arts of theatrical storytelling. Drukman’s play encompasses four decades, from the 1930s to the ’70s, and takes us all over America and occasionally to Hitler’s Germany to tell the tale of Louis’ rise and fall – and to celebrate, even mythologize, Louis’ relationship with his greatest opponent, German boxer Max Schmeling.

All the action takes place in a boxing ring, scrupulously recreated by scenic designer Lee Savage (the problematic in-the-round Cassius Carter Centre Stage has finally found its true calling). Through quick cuts and short scenes filled withy rapid-fire dialogue, we’re taken briskly through Louis’ rise to fame. Drukman makes it seem like Louis (Dion Graham) was discovered accidentally – a stuttering Detroit naïf whose boxing persona was created by a ruthless trainer (Al White, playing the legendary Jack Blackburn) and sports journalists (David Deblinger represents that ratlike, alliterative breed) hungering for a new champion. This is one of many places where Drukman compresses history and stretches the truth: Louis had already enjoyed a solid amateur career in Michigan and won the Golden Gloves by the time he stepped into the ring against boxing’s bigger guns. He wasn’t a shambling fool who came out of nowhere.

Drukman also takes liberties with the first Louis-Schmeling fight – one of Louis’ rare defeats during his prime. In Drukman’s script, Schmeling’s well-placed punch (he had studied Louis and discovered a small but exploitable flaw in his technique) happens quickly. In reality, it took 12 rounds for Schmeling to knock out his heavily favored opponent. Such truncations are arguably necessary to present a bio-play with efficiency, but they might rankle Louis fans. Drukman skates over other details, too, and gives short shrift to scenes that need more fleshing out. Louis’ tragic descent from a world champion to a penniless drug addict in a VA hospital is told schematically. The same could be said about Schmeling’s touchy, cat-and-mouse relationship with his Nazi overlords. Drukman’s script is filled with an embarrassment of riches; perhaps his subplots need to be winnowed to give the evening more focus. There’s plenty to admire in this production. Director Ethan McSweeny alternates between breathless speed with rat-a-tat delivery (think “His Girl Friday” as a boxing movie) and scenes of quiet revelation. But no director could make the boxing ring serve successfully as a dozen or more locales. At times (when a woman in high heels must squeeze through the ropes, for example), it’s just too awkward a forum for non-fighting scenes. The five supporting players provide a gallery of characters, many of them 1930s archetypes. Deblinger’s sports columnist, spouting creatively racist nicknames for Louis, seems pulled from “The Front Page.” Katie Barrett shows amazing range as a torch singer, a nurse, a starchy FDR factotum and a reporter who carries on a clandestine affair with Louis. T. Ryder Smith does a bang-on imitation of a breathless Golden Age boxing announcer and steals the show with a profane paean to the ring’s referee. (I’m not sure what to make, though, of his homoerotic Hitler.) White brings a combination of hunger and world weariness to Louis’ trainer. John Keabler provides some pre-show oohs and ahhs as young pugilist going through a rigorous training routine. But this show belongs to Graham and Rufus Collins, who plays Schmeling. Graham makes the most of the tension between Louis’ public stoicism and his private passions. Despite his luminescent fame, Louis was still trapped by the pervasive racism of the era, and that, more than the punches, took the greatest toll on the champion – a punishment that Graham makes tragically clear. Graham wisely underplays the scenes that show Louis’ descent, one of the most painful and tragic stories in sports history. Collins’ Schmeling is a deeply caring man with a lifelong compassion – and fascination – for his greatest opponent. That comes through most vividly in Schmeling’s scenes with the ailing Louis in the VA hospital, presumably around 1970 (another niggling inaccuracy – in real life, Schmeling and Louis re-established their relationship when they were brought together on the TV show “This Is Your Life” in 1954). A final, feeble boxing match between the fading champs is a poignant juxtaposition of old enmities, the cruel whims of fate, and the grim inevitability of age. Ending with a half-clench, half-hug, it’s a fitting end to a play that combines a welter of ideas – sometimes awkwardly, sometimes brilliantly – and refuses to simplify Louis’ twisted, sad life story. 1.11.08

SanDiego.com, Welton Jones – In writing the Joe Louis boxing play “In This Corner,” now on the Globe Theatre’s Cassius Carter Center Stage, author Steven Drukman rather obviously entertained vaulting metaphorical ambitions. He ends up wallowing in mere alliteration and stale hyperbole, his flights of poetical philosophizing finally more fancy than wise. Louis is a proud part of the royal line, from Jackie Robinson to Tiger Woods, who broke down race barriers in their sports. Only he was bracketed by more gaudy acts: Jack Johnson and Mohammad Ali. All Louis did in the 11 years he held the heavyweight title was to defend it successfully 25 times, an unbelievable 23 of those victories by knockouts. This despite a list of handicaps Drukman examines as if they were merit badges: youthful poverty, insanity in the family, a speech impediment, money woes, street drugs and, of course, the heavyweight champ of prejudices: race. Certainly plenty of that here. Each gets its moment of emphasis but there’s more, too. Louis gave up the violin for the fight ring? Hmm, OK, but that sounds an awful lot like sentimental 30s tear-jerkers. Visited late in life by his classic German opponent, Max Schmeling, Louis challenged him to a sparring match? Nice legend but again, is truth important? Maybe not particularly. This play makes no claims to strict realism. (That’s why the filter-tip cigarettes and the inaccurate uniform insignia aren’t especially important.) What Drukman and his director, Ethan McSweeny, want is flavor. And given the superior herbs and spices provided by this super cast, they get maybe even more than they deserve. Dion Graham bears an resemblance to Louis that is uncanny at times and he carries himself at all times with the big-cat grace of a heavyweight. Rufus Collins is completely convincing as the retired Schmeling (and barely acceptable as the young Nazi stud). But it’s the remarkable versatility and commitment of four supporting actors that gives the show almost as much atmosphere as the painfully accurate Lee Savage boxing ring set. T. Ryder Smith, who once played Abe Lincoln on this very stage, spreads himself over referees, rednecks and Joseph Goebbels with an intensity often near maniacal. He is burdened with the play’s most pretentious speech – a lumbering polemic about the symbolic relativity of the referee – but he also gets a chance to recreate, splendidly, the radio call of the Louis-Schmeling fight with all its evocative cadences pealing like a 20-ton church bell. Kate Barrett has the widest assortment of jobs, from ring floozy to presidential protocol rep, from USO blues singer to German movie star, from psycho ward nurse to news-hen, and she aces them every one, using whatever assortment physical tool applies in each case. They all play reporters from time to time, since Drukman is interested in the idea of Louis as a construct of sports media. (The theatre almost never gets newspapermen right – newspaper women more often, oddly enough – and this is no exception. Remember, though, realism here is more a matter of atmosphere. So these orgies of alliteration – the African Avenger, the Chocolate Chopper – should be understood as mostly decoration. David Deblinger does more reporter shtick than the others but he’s most effective as Schmeling’s canny Jewish manager. And Al White plays Jack Blackburn, Louis’ trainer and manager, with a conviction that cuts through the cliche. John Keabler, playing assorted other fighters and victims, doesn’t have a line but needs all his wind for the impressive pre-show workout onstage. He’s gonna be chiseled when this show closes! Nobody will learn much about boxing from this show. Or anything else, for that matter. It’s best seen as a musing on popular culture in a specific era and the dicey business of handling properly great champions who may be less than great human beings. But Drukman, McSweeny and their terrific cast do make Louis real enough to merit sportswriter Jimmy Cannon’s shrewd and touching epitaph: “He was a credit to his race, the human race.” 1.11.08

San Diego CityBeat, Martin Jones – Split Decision. Old Globe’s In This Corner is OK, but it neglects a huge piece of boxing lore. German heavyweight boxer Max Schmeling, who in 1936 handed America’s Joe Louis his first defeat, not only spoke spot-on English; his words were direct and simple, more like those of a teacher than a streetwise palooka who scarfed blood and uppercuts for breakfast. Both men, in fact, shared a refined, almost gentle nature. Young Joe was blinded by the fight game’s unforgiving ways, and it’s thought that the savvy Max eschewed the Nazi government’s equally cruel ambitions. Louis, the eventual world heavyweight champ, beat Schmeling in a rematch two years later. The men would later reunite outside the ring, once again under less than ideal circumstances. There’s even a play about it, called In This Corner, and it’s in a world-premiere run at The Old Globe Theatre right now. The piece is loopy with historical nuances, from Joe’s womanizing to the country’s racist bent (Louis was black, as you’re probably aware). But while author Steve Drukman clearly knows how to write that kind of subtext, he’s neglected a huge piece of the saga. The omission takes a lot of luster from the men’s mutual kindliness, especially at the climax, where it matters the most. By all means, see this play for its production values, which range from decent to damn good. One scene with an implicitly gay Adolf Hitler (T. Ryder Smith) practically steals the show. There’s some great physical contrast between Louis and his trainer Blackburn (Dion Graham and Al White) as the crusty veteran counsels the befuddled would-be warrior-“One good punch,” he snorts with the vim of a bull elephant, “is worth a hundred bad ones.” Graham makes a pretty good central figure, a sad casualty of the celebrity spotlight. Tyler Micoleku’s lighting design is as attentive as you’ll find, adroitly supporting the story without taking on a life of its own. It’s the climax that doesn’t follow suit. Schmeling (Rufus Collins), later an ultra-successful Coca-Cola exec, always considered Louis a personal friend and would visit him in a Denver psych ward in 1970 amid Louis’ drug addiction and clinical paranoia-but the scene reads flat and awkward, like a parley between a kindly insurance man and his marginalized client (watch Schmeling offer Louis his business card in exactly that manner). And in a play with so many nods to the past, one more would have fueled this crucial scene: To this day, Schmeling’s the only titleholder to assume the crown on a disqualification (in 1930, Jack Sharkey cuffed Max a little too close to the ol’ sleighbells, severely hurting him). That’s an enormous piece of boxing lore, vital in the path to the rematch and filled with grist for small talk between the men. Without it, director Ethan McSweeny’s hands are tied, though he does make do with what Drukman gives him. Louis, born Joe Louis Barrow in Lafayette, Ala., died in 1981 at age 66, hours after he attended the Larry Holmes-Trevor Berbick title fight. The workaday Schmeling would stick it out until age 99, passing in 2005. In This Corner is a watchable homage to the men and the colorful story that marks their careers. But for all its sense of history, it never quite reconciles itself in the final round. 1.15.08

sdtheatrescene.com, Cuauhtémoc Q Kish – Reviewing In This Corner allowed me a first (and probably the last) opportunity to find myself within such close proximity of a boxing ring. The ringside seat gifted me allowed lovely viewing of the activities imposed by the talented Director, Ethan McSweeny, who underscored the vintage period of the 30s with proper movement and vocal cadence. Before the show started I was thoroughly entertained by fit and trim actor, John Keabler, who was assigned billing as The Boxer. Warming up the theatre space he jumped rope, did push ups and sit ups and reminded me to seriously reflect upon that 2008 New Year’s resolution about working out with more gusto and conviction. Steven Drukman’s play paints a fine, limited portrait of Joe Luis but gives the ensemble of actors multiple opportunities to exercise their acting chops. All of them took advantage of the opportunities assigned to them. Katie Barrett struts her stuff in a bathing suit, a nurse’s uniform, and as a tough-as-nails reporter, among others. T. Ryder Smith and David Deblinger deliver up the goods as announcers and other roles while Al White remained evenly paced and stable as Louis’ trainer. Rufus Collins plays Max Schmeling with some nice conviction and Dion Graham’s Joe Louis is believable enough. In This Corner is all about two fighters (Max Schmeling and Joe Louis) losing and then winning in the ring and then winning and losing in life. No matter how many KOs Louis accomplished it still didn’t allow him entry into the white man’s world; America’s race card trumped any of his accomplishments he made in the ring. This play captures well the 30’s boxing era and transports you easily back in time to observe history in the making. It’s certainly worth a visit to the Cassius to observe the action in and around the ring. 1.14.08

North County Times, Pam Kragen – Media, boxing the targets of Globe’s compelling ‘Corner’. When boxer Joe Louis steps into the ring for the first time in Steven Drukman’s boxing drama “In This Corner,” he christens the canvas with a handful of Alabama red clay. It’s the soil from which he sprang —- a poor sharecropper’s son who would become the 20th century’s greatest heavyweight fighter —- and it’s symbolic of how he was shaped and molded like clay by the manager, sportswriters and announcers who carefully crafted him into a legend, then discarded him once his glory days were behind him. “In This Corner” was commissioned by the Old Globe especially for its Cassius Carter Centre Stage, and the arena space is a perfect setting for the play. Just as in real sports arenas, the audience sits on all four sides of Lee Savage’s authentically re-created boxing ring, watching attentively as the drama unfolds before their eyes. Yet while boxing is what these fighters’ lives were about, the theatricality of the sport was Drukman’s target, and the two themes marry well in his two-act, two-hour play about the mythologizing of sports heroes. “In This Corner” follows the rise and fall of the legendary “Brown Bomber” and his 30-year relationship with German boxing rival Max Schmeling. Yet while Louis is the central figure in the story, it’s notable that he’s practically mute in the play. Instead, the best monologues, dialogue and jokes are reserved for the colorful figures who surround the ring —- the hyper-protective manager, the cynical sportswriter, the arrogant ring announcer and the government leaders who cannily used the boxers for their own political gain. In his heydey, Joe Louis was an international superstar. He held the heavyweight title for an unprecedented 11 years and 25 title defenses, and during those years he was the subject of songs, dances and books, and thousands of children were named in his honor. His boxing career was practically unblemished, except for a shocking loss in 1936 to Germany’s Schmeling (who had detected a flaw in Louis’ technique), and their rematch two years later was one of the biggest sports stories of the 20th century. But as Drukman’s play shows, Louis was a god with feet of clay. Depicted by big-hearted actor Dion Graham as a stuttering, easily manipulated mama’s boy, he’s mothered by his no-nonsense manager (a perfectly pitched performance by Al White) and treated with selfish disregard by the casually racist sportswriters and announcers. In his later years, he’s a heroin addict, reduced to humiliating himself in costumed wrestling matches (Graham ages masterfully in the role). One of the strengths of Drukman’s script is his humorous homage to the alliterative, rhyming, purplish prose that peppered the sports pages of the ’30s. David Deblinger’s sarcastic Sportswriter crafts a wealth of ethnic monikers for the famed pugilists of the era, calling Schmeling the “Teutonic Tormenter,” Max Baer the “Hammering Hebrew” and Louis everything from the “Pious Pickaninny” to the “Sable Cyclone.” And he’s faithful to the style and energy of the radio announcers of the era —- re-creating in exciting detail the famous 2-minute, 4-second, Louis-Schmeling rematch, thrillingly performed by T. Ryder Smith. Globe audiences may remember Smith’s award-winning performance in last year’s “Lincolnesque,” and he’s just as compelling here in his show-stopping speech as the “third man in the ring” —- the referee/announcer.

A raised boxing ring is a directorial challenge, with ring ropes obscuring the sightlines and the difficulty actors face getting in and out of the ring, but director Ethan McSweeny rises to the challenge. He moves the play all around the theater, creates a snarky, cynical edge to the story and lightens and brightens the dialogue with rat-a-tat, screwball line delivery in New Yawk-ese (courtesy of dialect coach Jan Gist). The seven-member cast is excellent, particularly Smith, Rufus Collins as the cagey but generous Max Schmeling, and flame-haired sparkplug Katie Barrett in a variety of roles. Completing the cast is the athletic John Keabler as The Boxer, the godlike athletic ideal who wordlessly works out in the ring and plays a number of Louis’ sparring partners and boxing rivals. As the play concludes, Louis and Schmeling come together one last time, with the now-wealthy Schmeling (costumed by Tracy Christensen in a huge fox fur coat) extending a helping hand to the destitute, institutionalized Louis. They dance and parry, exchanging a vocal jab or two and then a real one. Their final headlock is as much a boxing stance as a hug, as they embrace their history and their age, and —- for a moment —- shut out the world that turned them both into legends. 1.14.08

Gay/Lesbian Times, Jean Lowerison – Boxers and acrobats in a lovely dance. Boxer Max Baer once defined fear as “standing across the ring from Joe Louis and knowing he wants to go home early.”

Baer should know. In 1935, two hours after Louis had married Marva Trotter, he stepped into the ring, KO’d Baer in the fourth round, and went off to celebrate his marriage.

In a 17-year career starting in 1934, Louis won 68 matches and lost three. In 2005, he was named the greatest heavyweight of all time by the International Boxing Research Organization and the No. 1 puncher of all time by Ring magazine. The Old Globe Theatre presents the world premiere of Steven Drukman’s In This Corner through Feb. 10, directed by Ethan McSweeny. The stage of the Cassius Carter appropriately has been converted into a boxing ring for the occasion. Both men were used as tools in their respective national political machines. Louis (Dion Graham) is perhaps best known as the African American who first lost to, then knocked out Nazi hope Max Schmeling (Rufus Collins) in the politically charged years 1936 and 1938, respectively. The war was about to break out and the “final solution” would come later, but the touted Aryan supremacy during and after the Berlin Olympics was on the line. Schmeling, the great hero of the Nazis after the first fight, so angered the Führer with the 1938 loss that he had Schmeling drafted and sent on suicide missions. (Schmeling infuriated Hitler further by refusing to become a Nazi, and, in fact, harbored two Jews during Kristallnacht.)

Meanwhile, Louis, born of poor sharecroppers in Alabama and lionized in the U.S. after defeating the German challenger, was still barred by Jim Crow laws from celebrating with his white buddies in local bars and restaurants. After his retirement in 1949, Louis, a generous man with time and money, was impoverished and forced into the wrestling ring to make a few bucks. He spent his last four years in a wheelchair and died in 1981 of a heart attack. Though these men were opponents, they were never personal enemies. In fact Schmeling, who after the war became a rich man representing Coca-Cola in Germany, paid Louis’ medical costs and reportedly served as a pallbearer at his funeral. (President Reagan bent the rules and had Louis buried at Arlington National Cemetery.) The relationship between sports and politics is a good topic for theater; it seems odd that this is the first play about Schmeling and Louis. In This Corner has some great elements and some that could use revision. Drukman does a good job of drawing the time period with costumes, music and three sports reporter characters, who demonstrate the alliterative purple prose that was prized in sports reporting of the day. Katie Barrett, the sole woman in the cast, gets a workout playing all six female roles – and proves well up to the task. Collins is a wonder – not only does he play Schmeling effectively, but he puts on a 20-minute pre-show demonstration of a boxing workout that made me wonder how he could even talk, let alone act afterward. Graham is somewhat less effective, I suspect largely because he adheres to his manager’s “never smile” admonition. That keeps him in character but limits his characterization significantly.

Mainly, though, the script (which was commissioned by the Old Globe) could use some reworking. There are too many short, staccato scenes and puzzling sudden time shifts that detract from continuity, so that the play comes across as a series of episodes rather than a cohesive effort. Extraneous material is introduced and dropped (for example, Louis shows up initially with a violin. Though it is true that he studied briefly as a kid, this seems unnecessary information here.) Al White as Blackburn and Dion Graham as Joe Louis in The Old Globe’s world-premiere production of ‘In this Corner,’ by Steven Drukman, directed by Ethan McSweeny, playing in the Cassius Carter Centre Stage Jan. 5 – Feb. 10. The best-written scene by far is the one in which T. Ryder Smith, as the referee, does his “third man in the ring” monologue. “You really think this is about you?” he says to the boxers. “Without me you’re nothing. I’m the third man in the ring …. I make the KO OK.” It’s a great piece of writing, splendidly delivered by Smith.

Drukman reportedly was struck by Schmeling’s chameleon-like ethical sense, but that does not come across in the script. There are ways to pump up the drama here. I hope Drukman reworks In This Corner. It is a worthy topic. 1.17.08

San Diego Jewish World, Carol Davis – Globe scores ‘KO’ with In This Corner. According to the rumormongers, heavyweight boxer Max Schmeling was in Hitler’s pocket, and was assumed anti Semitic. After all, he was part of Hitler’s propaganda machine; was in the Luftwaffe; was feted in Germany, especially by the Nazis, and was vilified in this country. From the German Press: “They trumpeted him as the perfect specimen of the Aryan superiority –beating the black American.” On the other hand, if you believe everything you read, Max Schmeling, the German heavyweight boxer who knocked out Joe Louis, the ‘Brown Bomber’ in round 12 of their historic heavy weight-boxing match in 1936, really was not anti Semitic or a pawn of Hitler’s but someone who actually saved the two teenaged sons of a Jewish friend by hiding them out in his Berlin Hotel room protecting them from the SS and Gestapo on Kristallnacht, eventually helping them escape Germany. As an extra topping on the cake, his agent in America was Jewish and he defied the German machine on more than one occasion. All of these assumptions are played out, including highlights and lowlights of both boxers’ careers in a new play currently being mounted on the Cassius Carter Stage of the Old Globe Theatre Complex in Balboa Park. In This Corner, written by Steven Drukman and directed by Ethan McSweeny, is a fast paced, fascinating look into the life styles and vicissitudes (if you will) of both boxers and as an integral part of that subject, an inside look at the sporting world of boxing, which I found intriguing. Is it all true? No. Has the playwright taken liberties? Of course. But it does make for good theatre. Furthermore, you don’t have to be a sports enthusiast to enjoy this piece. Druckman’s language is melodic, rhythmic and fun. It highlights the essence of an era, warts and all. As the young man sitting next to me commented on the way out, “When do you think this will become a musical?” If you are a student of history, however, it will take you back to the days when one of he biggest sporting events, set against a backdrop of an impending world war, captured a nation and “elevated Louis from an African-American hero to an All-American icon”. Given the times, however, the nation was still in racial denial and social inequity. Unfortunately, Louis was never able, in his lifetime, to overcome these prejudices. Under the new management team of CEO/Executive Director Lou Spisto and Co-Artistic directors Jerry Patch and Darko Tresnjak, Druckman’s world premiere production takes place ringside (Lee Savage and Tyler Micoleau, lighting) with all the accoutrements (ringside tables with microphones, typewriters, three legged stools, period telephones and a convenient place for the characters to change costumes (Tracy Christensen) to paint a boxing fan’s dream of the action to follow. The main ‘event’, if you will, is the rink where all the action takes place, ropes and all. Getting in and out between the ropes became a little hazardous at times, but it worked in that theatre. Five actors, playing multiple roles, over a period of forty years, make the whole picture believable, even though, in some cases, we know better. Their talent runs that deep. But fancy or fact, legend or truth the overall production is greater than the sum of its parts. No question, some of the wonderful dialogue gets bogged down with the rat-tat tat delivery, the rhyming verse and the overambitious need by the playwright to include too much gets wearisome and after a while you stop listening, but the play’s the thing, and this one scores a KO by evening’s end. Dion Graham who bears a resemblance to Joe Louis has embraced his role to a tea. His is tall, lean and while not muscle bound, could be mistaken as a heavy weight boxer by his movements and gait. At first I found him understated, not engaged or focused but as the play wore on and his story of Louis’ life intensified, he had it right and it paid off in the end. Louis’ story plays like a rags to riches to rags saga. From his humble beginnings, his becoming the world heavy champion to his decline into drugs, a bout in a mental ward of a VA hospital to his recovery, it’s like a soap opera. It is so skillfully portrayed by Graham, who is so soft spoken at times, that one wonders if Louis was actually that calm. Rufus Collins is a perfect Schemling, confident and reassuring. From his first appearance as the young German athlete ready to claim the heavyweight title at any cost, to his rematch with Louis to his disgust with the Third Reich and finally his last gestures helping a down trodden Louis, Collins carries himself with confidence, defiance at times, and with genuine sympathetic acts to a fallen comrade. T. Ryder Smith, who was fêted by the San Diego Theatre Critics Circle last year for his performance as Abe Lincoln in the Globe’s “Lincolnesque” is no less outstanding as he takes on the roles of ringside announcer, referee and Hitler among others. His calling of the rematch bout in 1938 couldn’t have been any more authentic sounding had you been there at the time. Al White is credible as Louis’ trainer, Jack Blackburn, and David Deblinger is right on target as Schmeling’s Jewish manager and ‘others’. Katie Barrett is ‘all the females’ and she is a standout as each and every one of them from Schmeling’s wife to the nurse in the VA Hospital to the USO blues singer to the Gal Friday news reporter to the German movie star. Rounding out the cast is John Keabler ‘The Boxer’ a little added value to the evening. Keabler, who played all the boxer fill ins, did some pretty fancy footwork jump roping while the audience eyed with envy, his stamina. With the departure of Globe’s longtime artistic leader, Jack O’Brien (emeritus), who will be making New York his permanent home, and the new troika steering the Globe’s ship. I expect we will see a lot more innovative and new productions reflecting their point of view on these stages. I’m excited. 1.17.08

San Diego Weekly Reader, Jeff Smith – Who They Weren’t. Right place, wrong timing: In 1938, a friend of mine’s great-uncle saved his shekels and went to the, at that time, Fight of the Century — the Joe Louis/Max Schmeling rematch at Yankee Stadium. Along with an estimated 70,000 others, he wanted to see “the Brown Bomber” demolish the Aryan brute who floored Louis in 1936 and who symbolized all things Nazi. Come fight time, the bell rings and Louis blazes, landing jabs and rocket rights. Schmeling goes down. Gets back up. “Gonna be a great bout,” the uncle thinks, why not make it perfect, with a good cigar? As he leans over to light up, he hears three dull cracks, like bullwhips on wet rawhide. The crowd explodes, stands, cheers. The uncle jumps up. Schmeling’s down. In the time it took to fire up his stogie, he missed the quickest TKO in heavyweight boxing history. Drukman’s In This Corner contends, a bit more often than need be, that history has missed something about Louis and Schmeling as well: the truth. The media turned each into an ideological icon, even though Schmeling detested Hitler (and sheltered two Jewish boys in his hotel from storm troopers); and Louis, once he stepped out of the ring, became yet another segregated African American who couldn’t have his picture taken with a white woman. The play retells Pygmalion. Depression-choked America needs a hero, and a hero needs a villain. So the media engineers them, out of words (many of them alliterative, often racist, tags). Louis, a gentle man who stuttered and liked to speak his mind, becomes a fabrication: a white’s ideal black man. He can clobber opponents, preferably with fury, but can’t smile or gloat and must remain subservient. When he steps out of the ring for good and the media can no longer exploit him, Louis nosedives from celebrity like an Icarus. For their first fight, Schmeling detected a flaw in his opponent’s technique: after a series of jabs, Louis would lower his left hand. Drukman’s world-premiere script also lowers its left: his characters exist more in theory, as verbal constructs meant to prove a point, than in depth. The play shows us who they weren’t, but who were Louis and Schmeling? We never learn, for example, why his manager chose Louis (the first time we see him punch, he has zilch skills). Plus, didn’t Joe philander, a lot? And the conclusion, which never happened (Louis is in a psych ward; Schmeling comes to visit in 1970), is weak. The playwright substitutes a thesis, that losing can make one born again, for a theory. The two square off and do a slow parody of Rocky III, when the Italian Stallion goes toe-to-toe one last time with Apollo Creed, as the credits roll. Druckman’s script has crisp dialogue and flashes of sharp writing (the ref does a set piece about order and chaos in boxing that’s a hoot) but could use more grounding. As if sensing this need, director Ethan McSweeny has drenched the Cassius Carter with atmosphere and detail. The stage is a boxing ring, a near-perfect fit, in fact: white canvas, frayed gold ropes, brown and black Everlast gloves dangling from turnbuckles. Four stations flank the squared circle, where actors watch, participate, and make practically unseen costume changes. Designer Lee Savage has raised the Carter’s floor three or four feet, to the same level as the audience. I’ve never seen actors’ heads that close to the ceiling before at the Carter. It makes the pugilists (even though their fight choreography’s pretty much by the numbers) loom almost larger than life. McSweeny has an affinity for the Carter. He directed last year’s Body of Water, which turned the intimate theater-in-the-round into a shimmering blue dreamscape. Often during In This Corner, he creates a soundscape. The banter straight from The Front Page, the pace of workouts, and the distinctive clack of an Underwood typewriter often have the fluidity of music. Joseph Louis Barrow was six foot two. Dion Graham, who plays him, not only has Louis’s height, he’s also got his eyes, at once fierce and quizzical, as if he sees double — and double standards. Graham, and a booming-voiced Rufus Collins, who plays Schmeling, fill in many of the script’s blanks with subsurface suggestions. The play’s about Main Event headliners, but McSweeny and a talented supporting quintet make it an ensemble show. As a reporter and a promoter (roles he makes reversible), David Deblinger talks like Louis de Palma on steroids. Al White’s smooth trainer-manager percolates with low-grade malignity. John Keabler plays various sparring partners/Louis punching bags, for which roles he prepares with a brisk, half-hour preshow warm-up. Katie Barrett, Craig Noel Award-winner for Mother Courage in 2006, demonstrates even more versatility as several different women, each sharply etched. Another Noel winner, T. Ryder Smith handles several assignments with skill. He cuts loose with the ref’s speech (“I make the KO okay”) and does the evening’s most dramatic sequence. Along with being about race and celebrity, In This Corner’s about pre-TV sports in America, in which words hyped, mediated, and at times mangled events. As an announcer, Smith calls the second Louis-Schmeling fight and shows that words could also describe indelibly. No one moves onstage. Instead we listen, to round one on the radio, and hear Louis’s genius combinations my friend’s great-uncle missed seven decades ago. 1.23.08

TheaterTimes.org – Stephen Drukman’s “In This Corner,” in a superb world premiere on The Old Globe’s ring-size Cassius Carter stage (through February 10), lets two legendary heavyweight boxers from the 1930s battle for personal dignity against the profit-and-propaganda process that turns people into products. In director Ethan McSweeny’s gritty staging, Corner’ drapes its message loosely over these real-life champs, allowing us to learn about the men beneath the mantles as we gain empathy for ‘products’ then and now, in sports and beyond, whose extended “entourages” aren’t so much in their corners as in their pockets. Central characters Joe Louis (Dion Graham) and Max Schmeling (Rufus Collins) reflect what, in hindsight, most ennobled their respective countries. African-American Louis validated our Algerian myth that all can succeed. Schmeling was a gentle man of humanity and an internationalist in an era of German empire-building and ethnic cleansing.

Several themes arc through the story like crosscutting trails off a shadow boxer’s gloves. There is the biographical material, told in an energized mix of flashback and forward motion. We learn much about them as individuals, their world championship fights in 1935 and ’38, and the mutual respect that served as friendship.A second theme, what Joni Mitchell called “the star-maker machinery,” concerns the anonymous pack of jackals Drukman uses to set up the play: ‘the reporter’ (David Deblinger), ‘the photographer’ (Katie Barrett), ‘the trainer’ (Al White) and ‘the announcer,’ played by T. Ryder Scott, who rises to the role oracle at one point. They shape a play about machinating media and commercial interests into which the fighters will step. That the champs wrestle the narrative away by play’s end suggests Drukman believes the individual is ultimately supreme. It certainly provides us a “feel good” play to take home, following a standing ovation at this performance and likely at most others.

A third theme emerges as the voice of this machinery. In the 1930s, radio added play-by-play sports coverage to its media arsenal. The world was still dominated by print media, but the electronic and broadcast segment had begun its move towards dominance. Families across the country now listened in unison to events like presidential addresses and heavyweight fights. And, in respect of that powerful presence, McSweeny stops the action to stage the 1938 fight merely through the power of words spoken first from the original broadcast, then picked up by Smith’s oracular ringside voice. The heightened language of the announcer, the sportscaster and the newspaper columnist give the show its bitter flavor, like a rum-soaked stogy. Drukman makes his point and dulls it with enough alliteration to give Howard Cosell salad-mouth. But it helps us see the parallels between the hypnotic power of speech incapitalist society and fascist society. The specter of Hitler (Smith) shows the “machine” at its most diabolical. While he and his ministers used athletes to promote their propaganda, America was using them to promote its counter-balancing righteousness. In a country where African-Americans had 30 more years of humiliating segregation before them, men like Louis (and later runner Jesse Owens), were asked to disprove the Reich’s fundamentalist Aryanism. In their first match, Schmelling prevails. In the second, Louis triumphs. Then, in one of their meetings before Louis’ death at 56, Drukman creates a decisive “rubber” round, as the two meet in street clothes, and, quickly winded, wind up clasped in a wheezing tie. As he did in 2006’s ‘Body of Water,’ McSweeny has assembled a fine cast. Graham is winning as Louis, keeping him somewhat vague as he may have been to himself. (Though, more clarity from Drukman on exactly what happened to him in terms of drugs and mental illness would be appreciated as long as we’re presenting those aspects.) Smith is a stand-out, as is the great Al White, and Katie Barrett assumes the position from hard-boiled photographer to chanteuse to gum-soled nurse to high-heeled ringside attraction. And, a special commendation to Collins for a memorable Schmeling as well as (with assist credit to coach Jan Gist) a fine, understated German accent. Ironically, the last time we felt a set integrated this well with its theater space was last year, next door in the Globe’s main stage with Ralph Funicello’s design for ‘Restoration Comedy.’ Here, McSweeny and designers Lee Savage and Tracy Christensen go for the total realism of a boxing ring, turning the audience into spectators, with “off-stage” actors “ringside” as much as possible. The “you are there” sensation begins during pre-show with John Keabler’s sweaty workout as “the boxer.” This detail accentuates the underlying metaphor of life in the ring, as when Louis bemoans: “We ain’t really nothing outside the ring Max,” or Max consoles his friend regarding public tastes: “Who are they? They aren’t even in the ring?” But the theme that Drukman floats like a butterfly is the flipside of language as instrument of propaganda. Drukman works the seeking of autographs into the story as an indicator of fame. However, after all the alliteration has faded, and the hype has moved on to other more potent “products,” the fighters are left alone with a final friend and the simple words that are their names. Today, the traditions of Midway journalism are as strong as ever. After experiencing ‘In This Corner,’ one may see our current celebrities with more empathy, as we are pummelled by their most-embarrassing pictures on tabloids that hang around check out lines like so much bologna in a deli. 1.13.08

sdtheatrecene, Pat Launer – The One-Two Punch. THE SHOW: In This Corner, a world premiere by Steven Drukman that provides the backstory and conjectured re-match of the fabled boxers Joe Louis and Max Schmeling, who met in the ring in 1938, and met again (so this story goes) in a psych ward in 1970.

THE STORY: It was an international incident, the sporting event of the century. The American nicknamed the “Brown Bomber” (Louis), in the ring with the über-Aryan German (Schmeling), on the eve of World War II. The fight would elevate Louis to the status of African American hero and all-American idol. Drukman hypothesizes a later meeting, when Louis has descended into alcohol, drugs and possibly, inherited mental illness. And Schmeling comes to visit him for one last go-round.

THE PLAY: More history than dramatic narrative, the drama (with occasional comedy tossed into the ring) is more cautionary tale than anything else, especially now, in the midst of the hotly contested fight we call the Presidential primaries. It’s not just about race, it’s also about the crafting and creation of a superstar. In the play (and presumably, in real life), the trainers and sportswriters took a hayseed Mama’s boy from Alabama and transformed him into a bombshell. There’s a funny scene where the ‘handlers’ riff on various alliterative names that might work to promote the young fighter (the Sable Cyclone, the Chocolate Chopper, the African Avenger, the Sienna Savage). Think spinmeisters, image-makers. The stardom they offer, of course, comes with a hefty price. The kid’s coach, Jack Blackburn, even sets out a few racially-sensitive, unassailable rules for Louis to live by, including ‘Don’t speak. Never have your picture taken with a white woman, and Never smile.’ Oh yes, and ‘Remember your ABCs: Always Be Clean.’ It’s these ‘wholesome’ and self-effacing behaviors that helped make an African American more palatable to white sports fans. But they still didn’t gain him admission to white clubs (another potent scene in the play). The piece sheds some important light on the racial divide in the early years of sports (and the situation was far worse before Louis came along). The play paints an interesting picture of Schmeling who, though he was an emissary of Hitler (who makes a brief appearance onstage), is also revealed to have harbored two Jewish children during the War, saving their lives. He has the potential for becoming a multi-dimensional character, but all we really get is sketches of the two powerhouse punchers. And there doesn’t really seem to be a moral or point to the story, though it creates a compelling portrait of a man whose breaking down of the racial barrier was earth-shattering in its time, but who somehow didn’t become as much a household name as Jackie Robinson. We do come to feel for the two men, both trapped in the national issues of their day, driven by forces beyond their control and their natural talents.

THE PLAYERS/THE PRODUCTION: The pre-show diversion is a show in itself. The theater is configured as a boxing ring (scenic design by Lee Savage). And in it, we watch hunky John Keabler, a student in the Old Globe/USD MFA program, warming up. It’s quite an entertainment. He works the bag, jumps rope double-crossed, double-time. And then he does it all over again, for an extended period of time. Impressive. The whole show builds up the steam and suspense of a real boxing match. Only occasionally do the ropes get in the way (making entrances and exits in a skirt is a little cumbersome at times for the sole female in the cast, Katie Barnes). But nothing else impedes her outstanding array of secondary characters, from a hard-boiled Noo Yawk journalist to a bathing-suit-clad beauty. She’s a knockout in every one of her multiple portrayals. T. Ryder Smith, last seen at the Globe in a splendid performance in Lincolnesque, is also fine in a number of roles, including Hitler. David Deblinger provides most of the comic relief, as a cigar-chomping Jewish manager, and a shirt-sleeved, rough-and-tumble, purple-prose-writing reporter. Al White is solid and credible as Louis’ sensible, no-nonsense trainer, though he seems to be channeling Morgan Freeman as Eddie Scrap-Iron Dupris in “Million-Dollar Baby.” In the central roles, Dion Graham as Louis and Rufus Collins as Schmeling are both compelling. They make the men and their relationship believable. But the ‘takeaway’ isn’t that clear. The performances and the story itself are riveting. Ethan McSweeny’s direction is superb. But it’s not clear what Drukman wants us to get or know. His rat-a-tat repartee is thrilling at times, but it also wears out its welcome; a few overwritten alliterations go a long way, and the humor deflates after awhile. The characters could be more sharply etched, and the point of it all could be clarified. Still, you won’t be sorry you spent some time in this very specific, confined world, roped into this ring.

La Jolla Vilage News, Charlene Baldridge – Old Globe’s bruising premiere. The theater gods descended on the Cassius Carter Centre Stage in Balboa Park, bestowing upon director Ethan McSweeny a thrilling, complex and well-made play, casting that could not be better and technical support par excellence. Commissioned by the Old Globe, the world premiere play is Steven Drukman’s “In This Corner.” Do not miss it.

Theatergoers remember McSweeny’s award-winning 2006 production of Lee Blessing’s “A Body of Water” in the same space, another tiny miracle, especially to those who prefer plays up close. One prays that the theater gods also smile on the Globe’s impending remodel of the beloved and intimate theater. “In This Corner” spans decades, beginning in 1933, when a youth rooted in Alabama’s red clay stumbles into a Detroit training gym and almost against his will becomes the Brown Bomber, Joe Lewis, who claimed the heavyweight title in 1937. As a boxer, Lewis was a creation of the press, his handlers and the times. As a creation of Drukman, his tragedy approaches that of Lear.

In the writer’s swiftly moving play, Max Schmeling — the German prizefighter who defeated Lewis in 12 rounds in 1936 and lost to him in a 1938 rematch — came to America in the 1970s and sought out Lewis, who was institutionalized. After retiring from the ring postwar, Schmeling became a wealthy and successful businessman, but Lewis — largely due to his extreme generosity and lack of practicality — ran up a huge IRS debt during his glory years. Like the Sword of Damocles, it hung over him the rest of his life. Some historians wrote that Schmeling and Lewis became friends. They go a few philosophical rounds — one of the play’s highlights. Drukman scatters duets and arias throughout, notably between Lewis and his trainer and Schmeling and his manager. During dialogue with Lewis, Schmeling declares boxing “the sweet science of bruising,” presumably lifted from “The Sweet Science,” a series of 1950s New Yorker articles written by A.J. Liebling, who in turn borrowed the phrase from Pierce Egan’s earlier sketches, “Boxiana.” Where boxing itself is wordless, Drukman is not. Amusingly, he capitalizes on the purple prose sports writing of the day and invents characters and situations enriched by language and imagery, tying together disparate social issues from an era when common racial and ethnic practices allowed discrimination against negroes at home and Jews abroad. Utterly convincing emotionally and intellectually, Dion Graham portrays Lewis. Rufus Collins is fine as Schmeling, a man of torn loyalties. The others in the company play multiple characters. T. Ryder Smith (“Lincolnesque”) changes facial hair and makeup ringside, right before our eyes transforming from boxing announcer to Hitler. Among other characters, Al White (“Two Trains Running”) plays Lewis’ trainer; David Deblinger, the press; and Katie Barrett, Lewis’ nurse and an unforgettable array of females. Prior to curtain, Globe/MFA actor John Keabler demonstrates the rigors of training.

Scenic designer Lee Savage transforms the Carter into a boxing ring, and though it’s irksome at times, all negotiate the ropes ably, indicating character and, in Collins’ example, touchingly, Schmeling’s aging (he really was the good German who in fact helped Lewis financially). Tracy Christiansen’s costumes are a joy and so are Lindsay Jones’ sound and Steve Rankin’s fight direction. Perhaps the most stunning of all technical elements, Tyler Micoleku’s lighting is another miracle of theatrical craft. 1.26.08

[previous] [next]