Photos by Doug Bost

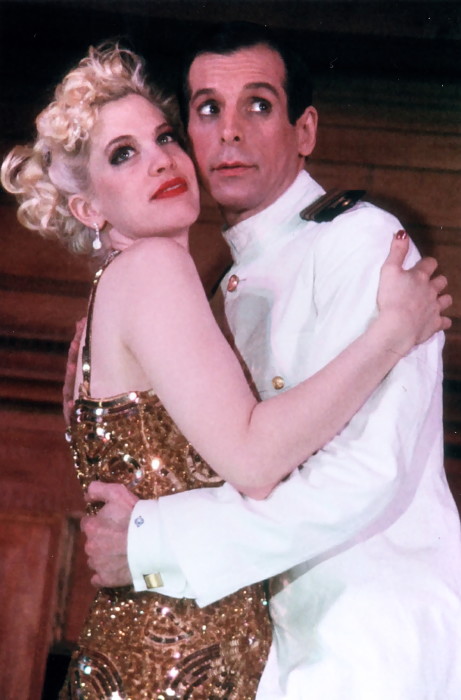

Above, from top: Carolyn Baumler and T. Ryder Smith; same; same, with Nina Hellman; Nina Hellman; Cynthia Darlow and Bruce Kronenberg; Dominic Hamilton-Little; Carolyn Baumler and T. Ryder Smith; ensemble.

Excerpts from the reviews

See full reviews below

“Smart, funny, and even a little irreverent towards West’s play. . . Carolyn Baumler is alluring and almost maliciously provacative . . . T. Ryder Smith, as Margy’s naval admirer, Lt. Gregg, is virtually a compilation of early American film depictions of British men; he seems to extend the notion of stiff upper lip to his neck, knees, back and elbows, to wonderful effect . . . This show is good comedy . . . “ – D. J. R. Bruckner, The New York Times

“In ‘Sex’, West spins a typical melodrama tongue-in-cheek – and her harlot emerges, well, on top. . . Elyse Singer’s production bursts with verve and naughtiness . . . sizzling jazz backgrounds . . . The able 10-member ensemble . . . tease their stereotypical roles into pungent farcical cameos . . . Also delectable are . . . T. Ryder Smith’s veddy British sailor . . . ” – Francine Russo, The Village Voice

“Mae West, the Pied Piper of the Libido, grows increasingly mysterious and awesome as time passes. Did such a woman really exist? The films are proof. They are works of a philosopher, a priceless vaudeville act that speaks convincingly of sex as the universal salve, with the prospect of the screw itself as the deepest source of delight. . . . Director Elyse Singer and her amazing cast have taken on a nearly impossible challenge in putting on this play, and the fact that it works at all is a marvel. . . . The sets and costumes are nothing short of sensational . . . T. Ryder Smith and Andrew Elvis Miller are a fount of amusement as the two twit suitors; that they are so consistently funny . . . speaks to nearly super-human will, not to mention talent. . . An astounding model of inventive direction and acting.” – Dan Callahan, Show Business

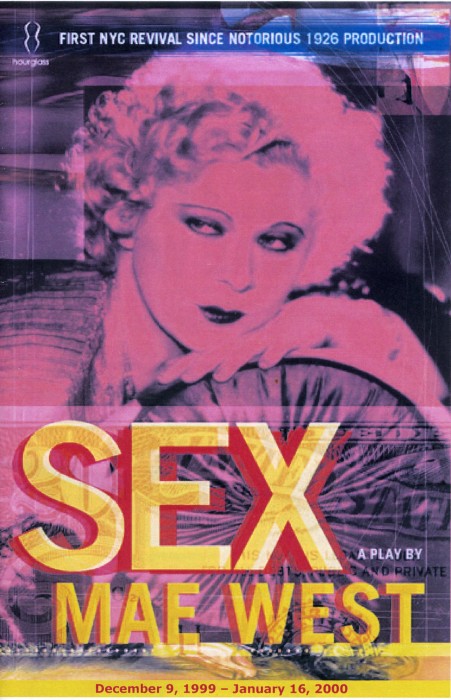

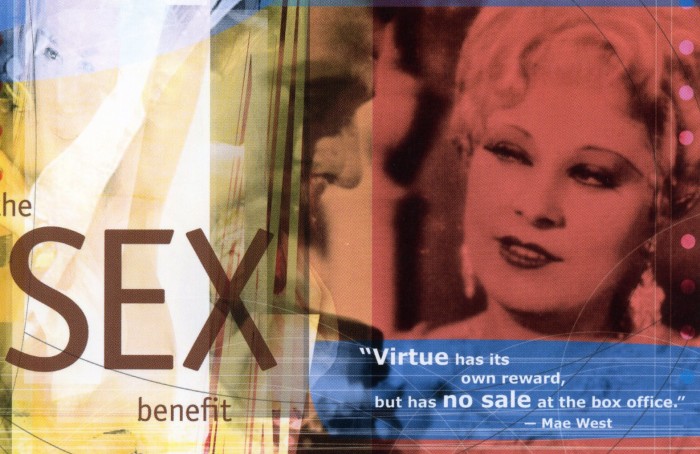

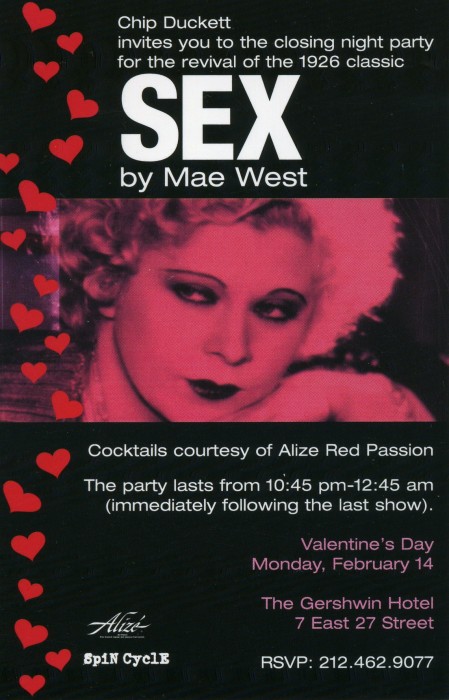

Publicity

Offstage

Back: unknown, Cynthia Darlow, Evan Hause, unknown, assistant director Ninon Rogers, T. Ryder Smith, Dominic Hamilton-Little, Andrew Elvis Miller, Pedro Sarrazino.

Front: Fred Velde, Nina Hellman, director Elyse Singer, Carolyn Baumler, Bruce Kronenberg.

Floor: Chuck Montgomery.

Full reviews

New York Times, D. J. R. Bruckner – Mae West’s First Play (for the Stage, That Is).If it helps a writer to know a lot about her subject, Mae West brought great authority to her first play, ”Sex,” written and first produced in New York in 1926. The writing is not as accomplished as it is in some of her later film scripts, but there are enough characteristic West lines to let you know who the author was, and it was good enough to get her tossed into jail in 1927 as the creator and star of an indecent public performance. As a publicity stunt the trial was perfect; from then on she was a star whatever she did. Oddly, the text of the play was lost for 70 years. So the show was never revived in the city. But now the Hourglass Group has resurrected it in a production at the Gershwin Hotel — a setting that has the 20’s written all over it — under the direction of Elyse Singer. It is smart, funny and even a little irreverent to West’s creaky plot and often corny dialogue. Ms. Singer is one of the three founders of Hourglass, and the other two, Nina Hellman and Carolyn Baeumler, play key roles. Hourglass itself is devoted to bringing attention to the work of women, but the production is by no means a captive of the playwright.

West’s plot is right out of the pulps. A bright young prostitute in Montreal, Margy (originally played by West, here by Ms. Baeumler), determined to get out of her racket and marry well, takes the advice of a British naval officer to ”follow the fleet.” That takes her to Trinidad, where she meets the naive scion of a rich family from Greenwich, Conn. He proposes to her and whisks her home to his parents’ sprawling mansion. Then the plot thickens. One of Margy’s Montreal boyfriends had seduced an American society matron — out slumming in a town where she wouldn’t be recognized — to follow him one night to Margy’s apartment, where he slipped her a mickey and stole her jewels. Margy and her naval officer friend return home, find the comatose woman and help her get back to her hotel. Of course, the woman turns out to be the mother of Margy’s fiance. And Margy’s sailor friend, who truly loves her, turns out to have been invited as a house guest by the fiance. The matron’s seamy escapade might be revealed and . . . well, you can write the rest of it. ”The only difference between us is you can afford to give it away,” Margy says to the trembling mother. There are many more needless complications here, but since most give rise to comic situations and good lines, what’s to object to? Ms. Baeumler is alluring and almost maliciously provocative as Margy, even if she displays little of the sense of mockery (including occasional self-mockery) that made West such a natural show-stealer. Ms. Hellman, first as Margy’s friend Agnes, a fellow prostitute miserably nostalgic for her rural religious past, and then as Marie, a maid in the Greenwich mansion, creates two comic characters so distinct it is hard to believe they are played by the same woman. Agnes, who would make a fitting bride for a scarecrow, all fray and no nerve, has a voice like failing brakes on a New York subway train, but louder. Marie, all curves, seduction and impertinent curiosity, purrs in a French accent that gets a laugh about every second word. Cynthia Darlow, a Broadway veteran, is hilarious as the society dame on a lark and even funnier as the frightened mother trying to evade the consequences. T. Ryder Smith, as Margy’s naval admirer, Lieutenant Gregg, is virtually a compilation of early American film depictions of British men; he seems to extend the notion of stiff upper lip to his neck, back, knees and elbows, to wonderful effect. And Andrew Elvis Miller as Margy’s clueless young fiance is a delicious contrivance; he manages to look like a wax mannequin that talks like a book, with so much sincerity he makes honesty seem quite obscene. Little else in the play sounds obscene at all, despite the long strings of innuendo that always marked West’s writing and speech. Hourglass surrounds the acts of the play with snippets from the 1927 trial of West, which is probably a good idea because few in the crowd this company attracts can have been 10 years old when West died in 1980 and probably have little idea how the legend began. The scene in a hotel cafe in Trinidad gives the troupe a chance to liven up things with some 20’s songs, and sound tracks by Steven Bernstein’s Sex Mob thread modern jazz, intelligently anchored in that era, through the whole evening. Altogether, this show is good comedy, if sometimes at the expense of the script, and for those who can remember Mae West alive, it is also a gentle nostalgia trip. 12-24-99

Village Voice, Francine Russo – West With the Might: What do the 1926 Sex and the 1999 Extreme Girl have in common? Plenty, from slinky lingerie and a red velvet sofa to some ballsy attitudes about women. Of course, Mae West was ahead of her time—pulling 10 days in jail on a morals charge for her play. It wasn’t just the hip wriggling and smutty asides that outraged reigning decency. It was her kick in the groin to establishment hypocrisy.

In Sex, West spins a typical melodrama tongue-in-cheek—and her harlot emerges, well, on top. Margy, the Montreal working girl originally played by West, is unashamed of her trade and unafraid of her thuggish pimp. When he drugs and robs a rich socialite, leaving her nearly dead on Margy’s hands, Margy rescues her. When the victim, afraid for her reputation, frames the helpful whore, Margy swears revenge. She beats it out of Montreal, takes Trinidad by storm, and, in a neat twist, finds love, revenge, and moral superiority all at once.

Elyse Singer’s production bursts with verve and naughtiness. She directs in a style both of the period and mocking it, interspersing song and dance interludes derived from trial documents. These slightly amateurish tableaux work fine but are really unnecessary—West created her own ironic distance within the play. Songs from West’s movies intensify the period flavor, as do an onstage piano player, fabulous flesh-tone undies, and sizzling jazz backgrounds.

The able 10-member ensemble, playing 17 parts, tease their stereotyped roles into pungent farcical cameos. Carolyn Baeumler lacks West’s gritty ballast, but her saucy, cynical Margy has zing. She makes the raunchy most of her double entendres, shaking her boobs and leering: “These may not be jelly, but they will get you in a jam.”

Also delectable are Nina Hellman’s homesick prostitute Agnes, T. Ryder Smith’s veddy British sailor, Andrew Elvis Miller’s androgynous rich boy, and Cynthia Darlow’s thrill-seeking matron. 12-22-99

Show Notes, Glenn Loney – Those who know about Mae West’s astonishing film-career may have heard that she also wrote and starred in plays back in New York before she conquered Hollywood.

That’s very true, but West was interested in showing the theatre-public what the seamier side of life was really like. Polite Social Comedy was not her forte: “Is that your pistol in your pocket, or are you just glad to see me?”

For Mae West, marrying for money and preserving the social facade of a gracious lady did not really make Mrs. Gotrocks all that different from show-girls, gold-diggers, or street-walkers.

The hypocrisy of Society—concerning sexual desires and kinks, as well as who “belonged” and who did not—was something Mae West was able to expose with both songs and scenes—and a lot of low comedy.

The recent small-scale but big-hearted revival of “Sex” not only lets modern audiences see and hear what appalled the City’s vigilant Moral Censors way back in 1926, but it also puts the performance in the context of that time and the trial which sent Mae West to jail.

Given the recent moralist fulminations of the Mayor about “obscene” art-exhibitions—and other offenses against Decency and Religion—this production has a special resonance.

It has been performed—and extended several times—on a tiny stage in a tiny room of the Gershwin Hotel on East 27th Street. This is not the Gershwin Theatre or Condos. It is a functioning hotel with an extremely funky lobby decor.

The ingenious concept of the production—and the charm and energy of the players—have made this one of the more enjoyable theatre-evenings of the season.

Carolyn Baeumler, in West’s starring role, is a vampish delight. But the entire cast, each in his or her own style, is great fun to watch.

Now perhaps someone will revive Mae West’s “Pleasure Man,” in which she put limp-wristed, simpering Drag-Queens on stage? This play was even more offensive, for obvious reasons.

Even more transgressive of Moral Values back in the Jazz Age was Mae’s drama “Drag.” She just wouldn’t give up in her attempts to confront theatre-goers with real truths about how some theatre-folk lived—not to mention some of the formally-dressed “Stage-Door Johnnies” in the audience.

Just before the Age of the Great Depression, in the era of Flappers and the Charleston, New York City passed the Wales Padlock Law to close down theatres purveying immorality and smut.

Mayor Giulilani might want to check if this law is still on the books? He could extend it to museums as well. How about a big fat Padlock on the Brooklyn Museum of Art?

Over a decade ago, the trio of talents who run Glasgow’s Citizens’ Theatre asked me to get them a copy of “Sex.” They wanted to produce it as part of their brilliantly eclectic repertory.

Over a decade ago, the trio of talents who run Glasgow’s Citizens’ Theatre asked me to get them a copy of “Sex.” They wanted to produce it as part of their brilliantly eclectic repertory.

I found it impossible to get a copy of the script. Nor were performance rights available.

When I was advising Dr. Richard Helfer on his CUNY PhD Dissertation research—for a study of West and her banned plays—we found it impossible even to quote lines from the plays.

The Mae West Estate must have had a recent change of heart.

Village Voice, Michael Feingold – Mae in January. For the moment, Western drama seems to have become Mae West-ern drama. West made a cameo appearance in the York Theatre’s recent Jolson & Company (not seen by me); Dalí’s famous portrait of her face as a seductively furnished bedroom inspired set designer Neil Patel’s best moment in Lobster Alice. The rowdy revival of her own first play, Sex, has just been extended through January. And now comes Claudia Shear’s Dirty Blonde, directed and “co-conceived” by James Lapine, which alternates dramatized snippets of West’s career with the story of a contemporary boy and girl who both worship West, but can’t decide which one has the right to dress like her.

The craze has its validity. Apart from being an artist of exceptional interest in her own time, West makes a highly viable icon for an era when definitions of both sex and art are widely contested. We don’t know what’s permissible and impermissible anymore, or even what’s male and what’s female. A bundle of paradoxes and confusions in herself, West’s admirable gift was to embody—surely the mot juste—everything that confuses us, on both topics, in one smirking epigram, or one roll of her corseted hips. However crude when she was starting out or grotesque when she got much older, her sex appeal was always a matter of comedy. Yet West was at the center of not one but three major censorship uproars: Sex was shut down by the NYPD (largely to prevent her bringing in her queer-celebrating second play, The Drag). She Done Him Wrong and I’m No Angel made so much money, and caused such clamor among the bluenoses, that they were the chief cause of Hollywood’s tightening the Production Code in 1933. And in the late ’30s, after an appearance on Edgar Bergen’s radio show, she was virtually banned from broadcasting. (She told his dummy, Charlie McCarthy, “Come up and play in my woodpile.”)

The irony was that West’s sensibility was not too new for the censors whose hackles she raised but too old—the standard repartee of burlesque and lower-class vaudeville, circa 1890, with its standard physical accompaniment of raised eyebrows and undulating shoulders. That she used the style to make herself, as performer and writer, a locus for a wide range of sex-related issues shouldn’t obscure the fact that she was a period piece, so to speak, from the very start. (Shear’s play suggests that the source of West’s ’90s style was her controlling mother.) She stands as a teasingly ambiguous rebuke to the fake sophistication and postwar disillusionment of the Jazz Age. We knew all about it before, her persona says; there was no need to topple monarchies and invent modernism just to face a little reality. Paramount, which put her firmly in the 1890s from her first starring role on, knew exactly what it was doing when it tried to obtain for her the film rights to Shaw’s Mrs. Warren’s Profession; one can easily imagine her both justifying the procuress’s trade and defending her daughter from it. (She is one of the few female stars of the 1930s to willingly play scenes in which she nurtures younger and prettier women.)

That she was a conscious archaism of course only got the censors angrier. The self-important hate nothing more than being mocked, and West’s Bowery-melodrama fun kicked them right in the center of their equally Victorian (but more bourgeois) sensibilities, where the Freud-ian subtleties of a Philip Barry or S.N. Behrman would pass them by unnoticed. Hence theviolent reaction. West had a wide range of sympathies, and her jokes can cut in a great many directions. African Americans, even the giggling maid who peels her a grape, are more like human beings in her pictures than in others of the time; homosexuality, though unmentionable after the police debacle of The Drag, has a persistent, quietly hovering presence. Abortion, prostitution, and battered-wife situations crop up glancingly; a tragic subplot of Sex contains vague hints of then-incurable venereal disease. And at the center, whether the character is called Margy Lamont, Diamond Lil, or Klondike Annie, there is always Mae West, the woman who revels in male attention but has no interest in becoming an object of male ownership.

In another sense, though, West is feminism’s camp opposite—the heroine of Parker Tyler’s gloriously convoluted theory that she appealed to male homosexuals because her matronly look and throwback attitudes represented a gay man’s mother taking on his postures to signify her acceptance of his ways. Certainly a lot of gay men over the decades have taken on her gestures and appearance. The twist in Dirty Blonde is that the male character, played by Kevin Chamberlin, who we’re set up to believe is the typical West-imitating drag queen, turns out to be a straight cross-dresser, a white male heterosexual who finds freedom in the ’90s gown and picture hat just as the actress manqué played by Shear does. It’s a love affair of dueling Mae Wests. Given the flashes of biography with which it alternates, it’s also a joke on West’s own narcissism. The thought of two Mae Wests clinching in the dark would have enthralled her.

The trouble with Dirty Blonde is that it goes no further. We get a quick survey-analysis of West’s career. And we get scenes, some touching, from the two Westians’ improbable love affair. But all that holds these parallel strands to-gether is Lapine’s creamy-smooth, visually hieratic production. Shear, brash and mellow, is always fun to watch; Chamberlin, a wistful pink boulder of a man, matches her ably. Bob Stillman handles the musical chores, plus a string of small parts, with appealing nimbleness. If you wonder later why they bothered, it won’t be because you had a bad time.

Much the same applies to Elyse Singer’s staging of Sex, brasher and coarser than Dirty Blonde, but equally straightforward in its innocent contemporaneity. Here West is saluted as an anti-censorship heroine—both acts open with excerpts from the 1926 obscenity trial that closed Sex—but her persona, and her writing, are praised as early avatars of camp. At its best, Singer’s staging is high-quality travesty in the old style; at its worst it degenerates into mere shouting. But Carolyn Bauemler’s Westian heroine sustains a sexy dignity inside the staging’s exaggerations, and so do T. Ryder Smith as her English lover, Cynthia Darlow as the dowager she one-ups, and Andrew Elvis Miller as the rich boy she nearly snags. If the noise level’s high for such a small space, so is the authenticity, once you peel away the outer grapeskin of camp intentions. 1.18.2000

[previous] [next]