Photos by Craig Schwartz

Excerpts from the reviews

Full reviews are below

“A rousing, cut-throat political drama . . . [Francis] is a skinny, awkward loner of grave and contemplative mein often to be found abroad in Washington, D.C., spouting fragments of familiar speeches and insisting he be addressed as Mr. President. Or just Abe. . . A former genius political wonk, he snapped under the strain, and now is at large only because he has a loving younger brother to sign him out of the asylum, The biggest difference between brothers, we’re told, is that the younger hasn’t the talent or intellect to go crazy. Instead, he labors as a speech-writer for a most unpromising congressman, facing cruel defeat. Goaded by a storm-trooper Valkyrie [boss], the younger brother turns for help to his sibling, who provides the wisdom that is, well, Lincolnesque enough to rebuild the candidate . . . Joe Calarco’s sterling direction hides the clunks and glosses over the unlikely reaches with the sprightly pace that makes the political fantasy work . . . T. Ryder Smith makes a Lincoln worthy of Elwood P. Dowd . . . He doesn’t become Christ-like and he resists being pulled too far into the author’s is-he-or-isn’t-he (crazy) musings . . . An interesting play . . . A superior production . . . it obviously deserves attention.“ Welton Jones, SanDiego.com

“A provocative world-premiere . . . Strand’s characters are compelling and excellently portrayed, especially by T. Ryder Smith as the often-lucid lunatic . . . Tall and slender, slightly stooped, and positively beatific when he speaks some of those glorious words . . . The insights about war, politics, and our underlying need for a hero really hit home.” Pat Launer, KPBS, San Diego (NPR)

“A mildly absorbing, deeply cynical political drama . . . Strong acting by all and tight, fluid direction keep the proceedings buoyant . . . Strand gives us two endings, the first falsely happy, imbued with wistful, mock-idealistic notions of family and community, and the second emphatically dark . . . This downbeat coda offers a sharp, disturbing contrast with real life in Washington, where, Strand suggests, the grimmest realities are inevitably greeted with political calculation and unrelenting cynicism. Likeable but only intermittently provocative, Strand’s play needs more of this unexpected pungency to provide a compelling, and not merely pleasing, evening of theatre.” Jennifer De Poyen, Variety

“A smart new political comedy . . . the dialogue is natural, tightly written and continually funny. [Strand] also makes some pointed observations of contemporary American politics . . . Smith is exceptional as the mentally-ill Francis. He bears more than a passing resemblance to the beardless Lincoln, but doesn’t attempt to imitate him. Rather, he blends the legendary Lincolnian aura of of gentleness, quiet grace, calm under pressure, and kindness with physical poses we associate with Lincoln’s photographs . . . And his resonant delivery of Lincoln’s best speeches inspires the same admiration today as it must have nearly 150 years ago . . .” Pam Kragen, North County Times

Craig Noel Award

For Outstanding Lead Performance.

For more, see awards page here.

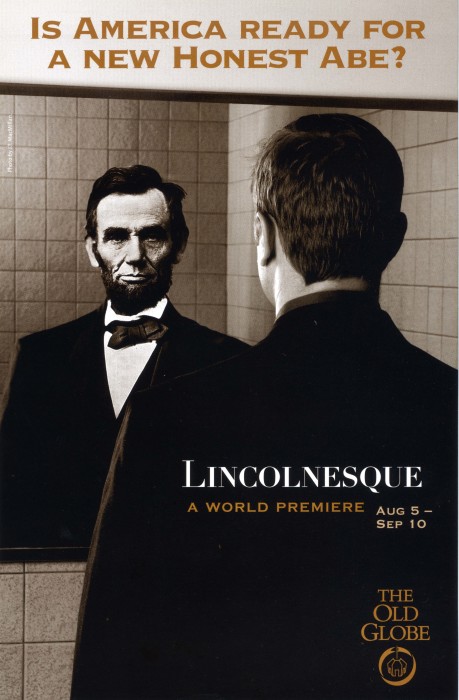

Publicity

irantrave.com: Acting Like a Dead President: Lincolnesque Actors Open Up About Their Craft, by Kate Kowsh

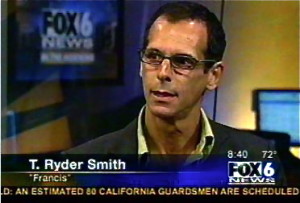

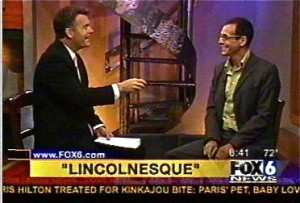

In any other context, a man who parades around, believing he’s “Honest” Abe Lincoln would be hogtied and carted off to the local psychiatric facility for evaluation. But when T. Ryder Smith does it, he’s applauded. In fact, it’s his job. As part of the cast of Lincolnesque, a dark, satirical, political comedy, soon to makes its world premiere at San Diego’s Old Globe Theatre, Smith once again has the chance to exercise a skill he says he’s been crafting since birth; the ability to be walk around in someone else’s shoes for a while.

irantnrave.com correspondent Kate Kowsh caught up with Actors Leo Marks and T. Ryder Smith to talk about preparing for their latest production, and what it’s like to pretend you’re someone else for a living.

irantnrave: So, tell me about the play.

Leo Marks: Well, we’re brothers

T. Ryder Smith: Yes, we are both working in Wash. D.C. at the present time, in politics.

Leo: I’m a speechwriter for a congressional representative who’s running for re-election. Not a very exciting position in politics. And, the campaign is struggling along. I happen to have a brother who used to work in politics.

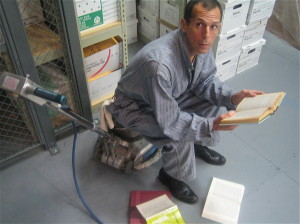

T.: I guess Leo works in politics in reality and I work in politics in my head. I’m convinced that I am Abraham Lincoln-reincarnated, which tends to give Leo cause for concern. I walk around making speeches and speaking like Lincoln. I don’t look like Lincoln, I don’t try to dress like Lincoln, but I believe I am Lincoln.

irantnrave: Sounds very interesting. Tell me a little about how you get ready for a production like this. After you get the part, how do you take it on?

Leo: (laughs) Boy, that’s a large question. We just try to get to know the play and understand what’s going on; try to put yourself in that world. (Directs his attention to T.) Say something funny. (laughter)

T.: You make it up as you go along, basically. I mean the process starts, I think, at birth, but then we pick up here. (laughter) I think you’re kind of drawn to different scripts after a while. They find you. So, John Strand [the playwright] created this piece; this dark political comedy. (motioning to himself and Leo) The casting director found us and there was some kind of affinity that she felt for us and we felt for the script and that the playwright and director felt for us in the audition.

irantnrave: I see.

T.: And we all wind up in the same room around the script. What you’re trying to do is, just, like Leo said, you’re trying to figure out, “What is this event that exists for us right now only as something we’ve read, something we’ve imagined, something we’ve auditioned for. How do we bring that to life so that it’s as exciting, rich, funny and strange as the thing we read on the page; the thing the playwrights thought of; the thing the director saw in his head when he read it; the thing the producers saw when they read it. How do all these people come together and make this event that will do the same thing for the audience that it did for us?’ Now we’re starting the third week and we ran the show for the first time from start to finish [earlier this week] and it was surprising, as always, to see what…worked, what felt solid, what didn’t work at all, what was completely unfunny, that we thought was very funny in our heads and what was surprisingly funny.

irantnrave: So, just to get a little history on you both, Have you ever worked together before?

Leo: I live in L.A.

T.: And I live in New York.

Leo: But we knew each other.

T.: Yeah.

Leo: I lived in New York for a long time.

T.: Back in the twentieth century. (laughter)

Leo: Then I moved out here six years ago. But yeah, we were part of the same world there.

T.: We never did a show together, but we did readings, and workshops together.

irantnrave: So, how long have you both been acting?

Leo: Forever

T.: Yeah. You’re born an actor, aren’t you?

Leo: Yeah, I guess so. I’ve doubted it sometimes, but I’ve never been able to get very far away from it.

irantnrave: That’s funny. I feel the same about being a journalist.

Leo: Yeah?

T: I don’t know who it was that said it, but, you don’t become an actor, you realize you are one.

Leo: (nods) Yeah.

T: And, once you realize that, there’s nothing else you can do. Even if you’re trying to become, you know, an architect or a veterinarian or teacher, you’re still out there talking to trees. (laughs) It’s a calling. I guess we’ve been doing it forever.

irantnrave: What’s the most enjoyable part for you guys, during the process of putting on a play?

Leo: I think the best thing about acting is when you’re actually in a creative state onstage. You’re not just delivering something that you decided on in the past. You’re actually making it up right there. You’re actually surprising yourself. Your finding out what a particular interaction really. It’s like you find it out from the audience…because they’re seeing it for the first time, and you start seeing it for the first time. It’s the same way if you’re in a city you know really well, and then you have someone come visit you. You see it differently.

irantnrave: Now, what were you both doing before they asked you to be in Lincolesque?

Leo: (jokes) I was drinking in an alley.

T: (jokes) I was looking for another career.

irantnrave: Hilarious!

T: No, I was doing a show in New York, and I’d never been to San Diego so I was delighted at the prospect of coming to this part of the world. And, [also] doing a new play that’s courageous enough to take on politics—let alone a dark comedy…

Leo: I was thrilled with the script.

Lincolnesque runs from Aug. 5 – Sept. 10 at the Old Globe Theatre in San Diego’s Balboa Park. August 10, 2006

sdtheatrescene.com, Behind the Scenes by Jenni Prisk

Hello! Happy mid-August! Lovely weather right now, we are blessed. As we are on (most) of our stages too!

I loved Lincolnesque at the Cassius Carter, mostly because it is a play on and about words, which the actors deliver well. Sweet, deluded T. Ryder Smith plays Francis who thinks he’s Abe Lincoln, with gentleness and depth. Perhaps he is smarter than all the rest of us? Magaly Colimon is a beautiful woman who can be sexy and power-hungry in the same scene. The set is simple, the walls of the Carter are engraved with the Gettysburg, and lines like “a house divided against itself cannot stand” ring so true today. Craig Noel was in the audience and was greeted lovingly by all who knew him.

Full reviews

sandiego.com, Welton Jones – There’s always room for a rousing cut-throat political drama even when the country is NOT gripped by savage, greedy, divisive hysteria. And when was THAT not the case? In living memory? That’s the kind of weary cynicism that seeps through John Strand’s “Lincolnesque,” now premiering at the Old Globe Theatre, and ultimately slows an otherwise gentle, if unlikely, fantasy. Who is Lincolnesque is a skinny, awkward loner of grave and contemplative mien often to be found abroad in Washington. D.C., spouting fragments of familiar speeches and insisting that he be addressed as Mr. President. Or just Abe. This being a fable of the life political, this poor wretch is a victim of the city where all is cannibalism, carnage and butchery. A former genius policy wonk, he snapped under the strain and now is at large only because he has a loving younger brother to sign him out of the asylum. The biggest difference between the brothers, we’re told, is that the younger hasn’t the talent or intellect to go crazy. Instead, he labors ineffectively as a speech-writer for a most unpromising congressman, facing cruel defeat. Goaded by a storm-trooper valkyrie imported in desperation from industry, the younger brother turns for help to his sibling, who provides the wisdom that is, well, Lincolnesque enough to rebuild the candidate on the fly and capture the lead with sheer oratorical charisma. One way or the other, it can’t last. The author provides two endings _ a rosy fantasy in which everybody gets happy and a grim, cold bath of realistic defeatism _ and both are dutifully done, the former with idealistic irony and the latter with cautionary world-weariness. There are some good bits of script for the actors and a few wry juxtapositions of the Great Emancipator with the usual run of politicians (though care is taken to avoid specific national agonies) but the playwright has miscalculated, I feel, the power of his subject. Yes, there are ruthless jungle survival laws at work in national politics, but D.C. isn’t Armageddon. All kinds of people work there, from pathetic workaholics through scummy criminals to martyred dreamers, but they’re not titans, just guys doing their job. Strand allows them and their work an undeserved mythic mystery cloaked in a massive, ritual cynicism that boosts their self-esteem while obscuring how petty and unimportant so much of the work is. There also are some plot points that melt under scrutiny. Why is this guy a public menace who gets locked up? What is this electoral campaign in one congressional district when there’s no mention of any OTHER race? And does speech-writing really have such power? Joe Calarco’s sterling direction hides the clunks and glosses over the unlikely reaches with the sprightly pace that makes political fantasy work. And his design team specializes in subtlety, from Anne Kennedy’s dressing of a bureaucrat turned bum to Lindsay Jones’ soundtrack contrasting Aaron Copland’s spacious Lincoln music with fat sax dance tunes at the victory party. Michael Fagin’s scenery is positively monumental, too much so for the little Cassius Carter Center Stage, but Chris Rynne’s sympathetic lighting helps. T. Ryder Smith makes a Lincoln worthy of Elwood P. Dowd (friend to the giant invisible rabbit Harvey, remember?) in the way he accepts what props he’s offered. He doesn’t become Christ-like and he resists being pulled too far into the author’s is-he-or-isn’t-he (crazy) musings. Leo Marks is too hard on his character as the lesser brother, making a nice guy into a barely functioning nebbish, hag-ridden with self-doubts. You see his point, though, given the hag virtuosity of Magaly Colimon, every insecure guy’s nightmare of castrating female dominatrix. She gentles down a little too abruptly, but that’s the playwright’s fault, not the excellent Miss Colimon’s.

James Sutorius completes a tight and talented cast in the dual role of a big-shot D.C, fixer and the shattered homeless derelict, playing each with efficiency and adding a thoughtful contrast of how short the real distance between them may be. This is an interesting play which seems comfortable in its universe while the show is on, thanks to this superior production, but which raises questions of all sorts, upon further contemplation. That means the piece needs work and, since it so obviously deserves attention, probably should get the help it needs. 8-11-06

North County Times, Pam Kragen – Washington politicians fare poorly in smart, funny ‘Lincolnesque‘. In John Strand’s smart new political comedy “Lincolnesque,” a dull U.S. congressional candidate leaps in the polls after his speechwriter cribs inspirational phrases from Abraham Lincoln. While many of the set-ups in “Lincolnesque” strain credibility, it’s not such a stretch to imagine that a politician with Lincoln’s moral rectitude could inspire today’s voting public. The Washington, D.C., of Strand’s play —- now in its world premiere in the Old Globe’s Cassius Carter Centre Stage —- is a cannibalizing cesspool of backstabbing and corruption that drives its most ambitious citizens to the brink of madness and beyond. That’s what happened to the play’s lead character Francis, a brilliant ex-policy wonk who suffered a breakdown and now believes he’s honest Abe himself. Under the medical supervision of his younger brother, Leo (a wimpish speechwriter who’s cracking in the pressure-cooker world of politics), Francis feels it’s his responsibility to “emancipate” them both from the immoral capital city and retire to the Lincoln family homestead in Springfield, Ill. Leo agrees to go to Springfield only if Francis will secretly help him write the candidate’s speeches —- which borrow liberally from Lincoln’s inaugural, congressional and Gettysburg addresses.

Strand’s dialogue is natural, tightly written and continually funny. He also makes some pointed observations of contemporary American politics —- particularly the ethical and moral differences between the noble Lincoln and his less-than-noble modern counterparts. Francis explains to Leo that Lincoln was the Shakespeare of American politics, a man who inspired with the elegance and power of his words and ideas. “The common man needs heroes,” Francis advises, “Let his words be taller and he shall be, too.” What still needs work in “Lincolnesque” are some of the characters and situations.

It’s impossible to believe that Leo’s plagiarism (from the best-known political speeches in American history) would go unnoticed by the mainstream media for some nine months. And it’s an elaborate contrivance to have Francis work as a janitor for Daly, a campaign counsel for the politician Leo’s candidate is running against. A plot thread involving the overdose death of a mentally ill former Washingtonian also goes nowhere, but it does serve as a poignant reminder about how the city chews up and spits out its finest minds. Some characters could also be softened or given a few extra layers. Leo’s boss Carla, the chief of staff for the congressional campaign, is too one-dimensional as a soulless, sexually aggressive dragon-lady. And the character of Daly, the campaigner who befriends Francis then uncovers the speechwriting secret, takes a hairpin personality turn that feels sudden and out of character.

Director Joe Calarco has assembled a very good cast, though on opening night some of the characters were still finding their focus. T. Ryder Smith is exceptional as the mentally ill Francis. He bears more than a passing resemblance to the beardless Lincoln, but doesn’t attempt to imitate him. Rather, he blends the legendary Lincolnian aura of gentleness, quiet grace, calm under pressure and kindness with the physical poses we associate with Lincoln’s photographs (stiff-legged stance, hand gripping a coat lapel). And his resonant delivery of Lincoln’s best speeches inspires the same admiration today as it must have nearly 150 years ago. Leo Marks is a bundle of nervous energy, perfectly suited for the role of his like-named character, Leo, a speechwriter so undone by the stress of his job that he’s developed a stutter. Marks’ physicality and boyish innocence are a good match for this part of a young man struggling to stay afloat in a big man’s world. James Sutorius melts so invisibly into his dual roles as the dapper lawyer Daly, and a bedraggled mentally ill man who Francis befriends, that it’s hard to believe it’s the same actor in both parts. Serpentine Magaly Colimon does her best with the difficult character of Carla, but her performance seems outsized to those of the other characters in the play. Chris Rynne’s lighting is notable, particularly in his clever use of columns of light to represent the stone pillars that anchor monuments all over Washington D.C. And Michael Fagin’s in-the-round set design incorporates the words of Lincoln’s best-known speeches. Reading Lincoln’s words inscribed on the walls, and hearing them spoken anew by Ryder, confirms Francis’s observation, that in times of war —- be it the Civil War or today’s struggle in the Middle East —- Americans need a hero like Lincoln to inspire them. 8-11-06

Variety, Jennifer De Poyen – What if the spirit of Abraham Lincoln were unleashed in the cynical, money-grubbing, poll-watching, every-man-for-himself world of Washington politics? That’s the intriguing, if hardly novel, question at the heart of “Lincolnesque,” John Strand’s mildly absorbing, deeply cynical political drama preeming at the Old Globe. Set in the recognizable now, though without any overt references to current events, the play offers the unpalatable but thus far irrefutable suggestion that the only Lincolnesque figure likely to haunt the hallowed buildings on the Mall today is a flat-out lunatic, who is nonetheless saner than the suits who rule the land with faint pretense of democratic principle and barely disguised self-interest. That madman who speaks truth is Francis (T. Ryder Smith), a former boy wonder of Washington politics who snapped under the strain and landed in an asylum. Now, thanks to his brother and keeper, Leo (Leo Marks), a political speechwriter for a sorry excuse of a congressman, he’s back on the outside. He spends his nights polishing floors in the corridors of power and his days spewing fragments of moving, provocative speeches from the Great Emancipator. Whether Francis actually believes he’s the spirit of Lincoln reincarnate is left tantalizingly unclear. He’s lucid enough to write riveting, fortune-shifting speeches for Leo’s congressman, but nuts enough to hold cabinet meetings about the slave rebellion with his Secretary of War (the shape-shifting James Sutorius, also wonderful as the needy, greedy king-maker Daly). More potently, Francis’ relationships with his nebbishy kid brother and the sexy, ball-busting power broker (Magaly Colimon) who fuels Leo’s ambition suggest the utter lunacy of the “politics as usual” that governs our world.

Strong acting by all and tight, fluid direction by Joe Calarco keep the proceedings buoyant, even when Strand’s script tends to the obvious and the pedantic. (Is there a cliché more overworked than the mad seer? Is there anyone left out there who doesn’t despair of the yawning chasm between our problems and our politics?)

Michael Fagin’s austere set of miniature icons of Washington architecture keeps the actors towering over the institution’s ironic commentary, no doubt, on the smallness of today’s political giants. Chris Rynne’s hazy lighting design reminds us of the fog of war that envelops the current moment, and also suggests the gloomy cynicism that prevails, onstage and off. Strand gives us two endings, the first falsely happy, imbued with wistful, mock-idealistic notions of family and community, and the second emphatically dark: even cynicism has yielded to a stark, inescapable realism. This downbeat coda offers a sharp, disturbing contrast with real life in Washington, where, Strand suggests, the grimmest realities are inevitably greeted with political calculation and unrelenting cynicism. Likable but only intermittently provocative, Strand’s play needs more of this unexpected pungency to provide a compelling, and not merely pleasing, evening of theater. 8-13-06

San Diego Union-Tribune, Anne Marie Welsh – ‘Lincolnesque’ means well, but meanders. In John Strand’s new comedy “Lincolnesque,” a sharp-tongued political handler tells a delusional man dressed as Abraham Lincoln that he’s no more crazy than most of the people working on Capitol Hill. Striking a Great Man pose and speaking eloquently, the Lincoln look-alike deadpans: “Oh, faint praise.” That line draws the biggest laugh in this meandering and inconclusive play. Actor T. Ryder Smith, lanky like Lincoln and dignified, too, employs his piercing, deep-set eyes and expressive hands to become the still center around which the fanciful, oddly evasive action swirls.

As Smith’s Francis intones poetic, often less-than-familiar passages from Lincoln’s speeches, his biblical cadences and humble delivery make today’s bumbling leaders and many of their opponents seem pygmies by comparison. And that, of course, is Strand’s obvious point. Whether intentionally or through mental illness, Francis has checked out of the Capitol Hill merry-go-round. Released from St. Elizabeth’s into the custody of his speechwriter brother Leo, he’s doing better on medication and has landed a job as a janitor. We learn from this caring, if agitated brother (actor Leo Marks) that before his breakdown, Francis had been one of the great political strategists on the Hill, a man always far ahead of his opponents in the cynical chess game that American politics has become. But we’re also supposed to believe that this Rovian mastermind was some kind of admirable idealist and that his breakdown was caused by the corrosive nature of contemporary politics. Strand’s script doesn’t root the play in any one party or even era. Director Joe Calarco and his design team go along for the ride, so the Globe production that opened Thursday appears to be unfolding in some vaguely Washingtonian theater of the mind. Strand skips lightly over the issues raised by Francis’ mental illness, for it’s the Lincoln speeches, not plausible psychology or political vision, that the playwright needs to keep his plot chugging along. And the plot goes like this. Leo’s boss – a congressional mediocrity who stands for nothing – is falling behind in the polls. His campaign has brought in a corporate makeover artist named Carla (Magaly Colimon) to help. She blames Leo for the man’s plunging popularity, but her own scheme to resurrect his ratings has failed, too. Enter Francis. When Leo takes Francis’ advice and inserts a few Lincolnesque passages into his candidate’s speech, the campaign takes off. Potential voters feel inspired. The vision thing kicks in. Leo and Carla smell victory. Francis, now also an unknowing adviser to one of Leo’s adversaries, has other plans. He dreams of freeing his brother from the corrupting influence of Washington. So when Leo’s candidate wins – well, let’s not spoil the surprise.

Actor Marks makes a likable, if naive mensch of Leo, fussing about his older brother and easily seduced by the cold and calculating Carla. The woman is a stick figure, however, strident from her first words, and cruelly aggressive as Strand creates her. Actor Colimon gives an unpleasantly one-note performance, the artificiality of her speech rhythms reflecting the wooden writing. While she’s constantly jabbing her finger and strutting about, actor James Sutorius relaxes into both parts of his dual role as the street person Ed, who befriends crazy Francis, and as Daly, the most plausible of the political types onstage, a manipulator and amoral pragmatist. Like Smith’s Francis, who names his homeless buddy his Secretary of War, Sutorius finds a dynamism in his characters and naturally modulates their talk. “It pains me, Abe, to be alive,” Ed says before wandering off like an old dog to die. He humanizes Daly, whether this nattily dressed back-stabber is describing his reconciliation with his long-estranged wife or is viciously destroying an adversary. Though his characters are minor ones, Sutorius at least brings badly needed elements of empathy, passion and realism into this well-meaning, but vague and vaporous play. In the age of such dazzling, politically engaged writers as Tony Kushner, Caryl Churchill, Culture Clash or even the loquacious David Hare, Strand’s nostalgia for the rhetoric of the Great Emancipator proves a lame impetus for drama. 8-12-06

San Diego Union-Tribune reader’s responses – Critic’s choice of words showed her biases. I wanted to write in response to Anne Marie Welsh’s review of the play “Lincolnesque,” now showing at the Old Globe Theater (“ ‘Lincolnesque’ means well, but meanders,” Aug. 12, Currents Family). I’m an avid theatergoer and had heard good things about the play; I drove down from Los Angeles to see the premiere. I believe I attended the exact performance Welsh did. But apparently, we didn’t see the same thing at all. And given the standing ovation and ardent audience participation during the performance, perhaps she and the audience didn’t see the same thing, either.

It seems to me that the role of the critic carries with it a huge responsibility to the readers, who trust her judgment and recommendations. She is, of course, entitled to her personal opinion. But her role as a play critic should supersede her personal biases, since that role requires that she look at plays from a more general viewpoint of what is good art, important, less important, higher quality, lesser quality. And that responsibility carries through down to her choice of words: “vague,” “lame,” “vaporous” and “wooden.” These are not only lethal words to the playwright and production, but in this case, completely inaccurate for a play that had the audience alternatively laughing, moved, cheering, hanging on every word, and cheering at all the right times.

I’m not saying she should change her personal opinion, just her judgment and choice of words in reviewing a play for the public that was thoroughly enjoyable, very well written and acted, and I should say highly needed in San Diego and many other cities. Benjamim Bidlack, Los Angeles

San Diego Union-Tribune, Young People’s Edition, David Dixon – Leo is the only family that Francis has, but he’s so busy working that he doesn’t have time for his brother. Francis wanders the streets, with no one to guide him, and he starts to form a cabinet by hiring a random homeless man to be his secretary of war. This world premiere is a political and psychological drama that shows the ruthlessness of American politics. Not only does it have a fascinating story, but every actor in this cast of four does an amazing, five-star job. T. Ryder Smith, as Francis, is incredible in the scenes when he loses his grip with reality and goes into a psychotic state quoting speeches from Abe.

The only problem with this show is its advertising. It is billed as a comedy, and while it has funny moments, it also is a political drama with moments of insanity. The ending makes the audience ponder the implications of the story. This play is not meant for young viewers, not because of its language, but because its theme and issues might either bore or confuse them. “Lincolnesque” is one of the best new shows of 2006 and should not be missed by theatergoers over the age of 13. It’s a definite must-see.

Vyuz.com, Larry Knowles – Lincolnesque goes for laughs over dogma. Lincolnesque, the world premiere play running at The Old Globe until September 10, is billed somewhat dryly as a play that “explores contemporary politics and the legacy of Abraham Lincoln.” The billing, however, is a bit misleading. The play isn’t really about political intrigue or the legacy of Abraham Lincoln, themes that would be, frankly, pretty boring. Lincolnesque is instead a comedy, a well-paced, highly entertaining story of brothers who exasperate each other, adversaries who step on each other, and co-workers who spar—then sleep with—each other. Set in contemporary Washington, D.C., Lincolnesque, written by John Strand and directed by Joe Calarco, centers on two brothers, Leo and Francis, the former a speech writer for a U.S. congressional candidate, the latter a delusional janitor who thinks he’s Abraham Lincoln.

Leo looks after Francis, all the while trying to come up with speeches compelling enough to get his candidate back in the race. Enter a hard-charging, ambitious campaign manager who calls out Leo as hack, and a few subsequent speeches that sound strikingly Lincolnesque, and you have all the makings of farce. The comedy in Lincolnesque succeeds largely due to the casting. This is one of the few plays where every actor seems perfectly suited to and at ease in their roles. As a result, you have a confidence among the cast and chemistry between the players that allows for great comic timing. Everyone seems to be having a good time. T. Ryder Smith, who plays Francis, is spot-on not as Lincoln, but as a nutcase who thinks he’s Lincoln. He has the stolid persona and deadpan delivery of a man who really believes he’s one of the great political figures in world history. He’s at once complacent and compassionate, bombastic and lithe. Then there’s the voice. Let’s not diminish the importance of the voice in a character pretending to be a great orator. Smith speaks with a charcoal-filtered voice that adds gravity to his lines and credibility to his character. Leo Marks does a fine job as Leo. Playing a self-effacing speechwriter with a laundry list of esteem issues requires a great neurotic energy and Marks sustains a mania throughout the play. You want Leo to chill out at times and get a backbone, but he’s a toady through and through and this never happens. Magaly Colimon seems to relish the role of Carla, the man-eating, power-hungry campaign manager for the lame congressional candidate. Carla comes on like a freight train, all blind ambition, and a lot of fun comes out of her upbraiding and undressing the underling, Leo. James Sutorius plays the dual roles of Stanton, Francis’ indigent friend and “Secretary of War,” and Daly, the brash king maker behind the man running against Carla and Leo’s congressional candidate. Sutorius was so convincing in the roles that some audience members believed they were played by separate actors. The critique I have for the play is minimal, nitpicky stuff, reflective more of the playwright than the production. For example, Francis was fond of repeating variations Lincoln’s “A house divided against itself cannot stand.” The first time he threw out the line, it sounded insightful. The second time it sounded redundant, and the third time, just hackneyed. The repetition smacked of rote learning and undermined the premise that Francis was a sage operating on a higher level of consciousness. Another nit: At one point, Francis throws a fit and Carla, to calm him down, adopts the persona of a servile negro and addresses him as “Mr. President, suhhh!” Carla suddenly subjugating her ego so wildly seemed odd and capricious.

But these critiques are splitting hairs, and as we all know, “A hair split against itself cannot stand….” 8-16-06

San Diego Reader, Jeff Smith – Carnivorius Beltway. When it came to campaign strategy, Francis was a genius. The “whiz-kid staffer” thought like a chess master, many moves ahead. He was so smart, so sane, that Washington politics “devoured” him. The student of Abraham Lincoln “went mental,” and the only way to emancipate himself from the carnivorous beltway world was to withdraw into his idol, Honest Abe. When John Strand’s Lincolnesque, now in its world premiere at the Cassius Carter, begins, the real and the imagined blur in Francis’s mind. Whether he’s Francis or Lincoln, people urge him repeatedly to “focus.” He is — or is not — an outpatient at St. Elizabeth mental hospital (I’m trying not to give away the ending; it may come as a surprise, to some). Francis is taking his meds, he swears, and hasn’t heard voices in at least four months. He buffs floors and recites the words of our 16th president. “With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive to finish the work we are in…” Compared to today’s shallow political slogans, the “Lincolnesque” style — stately cadences, balanced antitheses, moral gravitas — resounds with an almost biblical authority.

John Strand built his play around a then-versus-now contrast. Instead of cautious, skimpy sound bites (which, said Washington columnist Meg Greenfield, has turned politicians into “full-time human captions”), when Francis quotes Lincoln, the words roar across time and illumine today. Of course, when it comes to the Washington D.C. subculture, which has even better liars than a used-car dealership, so do the words of William Blake: “Princes appear to me to be fools; they seem to me to be something Else besides Human Life.” Lincolnesque inches along and generates puzzlings about its craft as well as interest. The main plot concerns Francis’s brother Leo, a fledgling speechwriter obsessed with winning. A political Salieri to his brother’s Mozart, Leo writes dull words for a dull candidate. The campaign falls 15 points behind in the polls, and Leo’s draconian boss, Carla, demands results. So Leo makes Francis a ghostwriter: just a few phrases from Lincoln, “the Shakespeare of American politics.” Bigger words will make the candidate seem bigger! And Francis becomes the Cyrano of the campaign. He touches up his brother’s speeches and saves the day. Sort of. Since he’s allegedly buffing floors, Francis has at best a passive-aggressive approach. But so does Lincolnesque. Trying to fool all the people all the time, and offend no one in the process, the playwright made the background generic. We never know the candidate’s party, or Leo and Carla’s, or even Francis’s. Everything’s nebulous — explained by the ending, true — but also too general and abstract. Lincoln’s words gleam. But the rest of the play minces through a minefield, avoiding controversy to make its single point. As a result, it lacks bite and drama. When actors pause too long, between or during speeches, they get a note to “take the air out,” to tighten up their delivery. Lincolnesque needs air removed. Also, there should be more at stake. The play has the makings but is a draft or two from moving beyond a mild, cerebral evening to engaging drama. Beginning with the ending would take away the surprise, but the actual plight of the narrator could infuse each scene with more than mere nostalgia. It would also erase nagging questions that detract from the story: such as, wouldn’t at least one person in D.C. recognize Lincoln’s phrases? And why does everything seem so contrived (including the sudden 180-degree reversal with Leo and Carla)? It would also eliminate an ending that feels like an obvious gimmick. The play needs work, but the production values at the Cassius Carter are top flight. A visual irony rules the stage: costume designer Anne Kennedy put everyone in charcoal gray suits (adding color only for ties and blouses); scenic designer Michael Fagin locates the drama on a white marble floor (a miniature of the Lincoln Memorial also serves as a trunk for props). So what we see is black and white. And what we hear is anything but. T. Ryder Smith does a nice turn as Francis/Lincoln, drifting from one to the other and sometimes including both. He’s especially adept at striking a pose without posturing — as when his character stands on the base of a lopped-off Greek column, his forehead haloed by Chris Rynne’s expert lighting: is he the sage Lincoln or the possibly delusional Francis? Leo Marks, as Francis’s fumbling brother; Magaly Colimon, as the relentless Carla; and James Sutorius doubling as a homeless man and a soul-sucking D.C. mover-shaker — each fills in needed details for essentially one-dimensional roles. Marks is particularly effective as struggling Leo. He’s in so far over his head that his stutter sounds like gasps for air. And his frustrations and ineptitudes are some of the only genuine notes, other than Lincoln’s sonorous phrases, struck all evening. 8-24-06

KPBS San Diego (NPR), Pat Launer – Lincolnesque is the title of a new play, by John Strand, and also a description of its central character. Poor deluded Francis thinks he is the great man. He’s long and lean and wears a black cutaway coat. He stands on pedestals and orates, expounding eloquent Lincoln quotes, all of which, in the face of our current political climate, sound eerily relevant. Francis has recently been released from a psychiatric hospital. But he was once a brilliant Washington strategist. He befriends a hapless homeless man who also was once a major player. Francis is protected by his brother Leo, a speech-writer for a weak Congressional candidate. Now Leo’s up against a wall; his man is behind in the polls. His new, female, take-no-prisoners boss is putting the squeeze on him. And suddenly, he gets, as Dr. Seuss once said, “a wonderful, awful idea.” Francis becomes caught up in the “carnage” and “cannibalism” of the capital. As one monstrous politico reminds us, “In war or politics,” you want “professional killers… on your side.” Strand’s characters are compelling and excellently portrayed, especially T. Ryder Smith as the often-lucid lunatic. Director John Calarco keeps the action brisk and suspenseful. Only the schmaltzy underscoring is overdone. But the insights about war, politics and our undying need for a hero really hit home. My husband and I discussed the play for hours; like Francis, we couldn’t agree on the line between fantasy and reality.

San Diego Theatre Scene, Pat Launer – Holding Out for a Hero.

THE SHOW: Lincolnesque, a world premiere by John Strand, who happens to live in the D.C. area; clearly, he knows the slime of which he speaks.

THE STORY: Francis thinks he’s Abraham Lincoln. He dresses in a cutaway coat, and cuts a long, lean figure. He stands on pedestals and pontificates, reciting the greatest speeches of the Great Man. His brother Leo, always trying to protect him, has helped him get a job as a janitor, now that he’s out of the psychiatric hospital. But Francis just can’t help befriending folks, like a homeless guy he names his ‘Cabinet Secretary’ and in turn, the man, also spit back by the Beltway, happily calls him Mr. President. Leo’s got troubles of his own; he’s a speechwriter for a fairly lame Congressional candidate, who’s falling behind in the polls. So a new boss is brought in, a ball-busting woman who goes for Leo’s throat (and other parts). When they’re floundering and rudderless, they turn to Francis, who was once a brilliant Washington strategist, before he got eaten alive by the “cannibals” of the Capitol, and flipped out. Leo and Carla borrow a Lincolnesque phrase here and there. And their guy comes out sounding genuine, caring and concerned, not to mention spectacularly eloquent. The candidate wins, but all manner of havoc ensues, which makes us question who’s right, who’s a hero and where’s the line between fantasy and reality. It’s a well-written, surprising, suspenseful and intriguing play, which shines a bright but disquieting light on the destructiveness of present-day politics. And it’s getting a lovely production, under the assured direction of Joe Calarco, a playwright in his own right.

THE PLAYERS/PRODUCTION: T. Ryder Smith is a wonder as Francis; he’s truly Lincolnesque, tall and slender, slightly stooped, and positively beatific when he speaks some of those glorious words. Needless to say, politicians just don’t orate like that any more. And heaven knows, they rarely take the moral high ground. Leo Marks is wholly credible as Leo, a guy caught between expedience, the desire to be a winner, for once, and his responsibility for his brother. He’s the narrator, though we can’t always accurately view things – especially Francis – through his eyes. Magaly Colimon is bone-chilling as the tough-as-nails boss, Carla, and James Sutorius does excellent double-duty as the desperate, depressed and homeless ‘Secretary of War,’ and Daly, the ruthless, brutal Major Player in the political game. Michael Fagin’s scenic design is deliciously spare and suggestive: the American flag inlaid on a marble floor, parts of columns strewn about, and a ‘rotunda’ overhead. Projections of Lincoln quotes cover the theater walls. Very congressional, and beautifully lit by Chris Rynne. The sound design gets a tad too schmaltzy whenever the Lincoln words are uttered. But otherwise, this is a provocative and thought-provoking piece, absolutely worth seeing – and deeply examining. Could it all be a fantasy, or only certain parts? You be the judge.

La Jolla Village News, Charlene Baldridge – ‘Lincolnesque’ stands tall at Globe.Those who’ve hesitated overlong in front of the arts door stenciled Significant Change are encouraged to throw it open and enter the new world of the Old Globe.

Having joined the Globe 18 months ago, Jerry Patch is in full stride as resident artistic director, evidenced by the Globe debut of playwright John Strand with the Aug. 10 world premiere of his beyond smart and clever new play, “Lincolnesque.” Imbued with history, philosophy and politics, the work continues through Sept. 10 in the 225-seat Cassius Carter Centre Stage. The set-up sounds intellectual enough to put off one who expects the usual, something glib and puddle-deep. What one finds instead is a fascinating and philosophical exploration of what it takes to survive in an insane world; when and by what means do we check out; what is truly important; and what is wrong with politics and, by extension, America. Strand manages to imbue his characters with humanity and the ability, however obliquely, to address these issues. Francis (T. Ryder Smith) is delusional. When the play opens, he is Abraham Lincoln, in fact, delivering an 1858 oration that laments the ongoing War Between the States. Though he believes he is Lincoln, and though Copland-esque music a la “Lincoln Portrait” is heard in the background, he is jolted by the Washington, D.C., traffic whizzing by, even at 11:15 p.m.

Francis is rescued from the traffic circle by his brother Leo (Leo Marks), who writes speeches for a present-day senatorial candidate 15 points behind in the polls. That is, Leo tries to write speeches when he’s not trying to coax Francis back into the land of the living. Evidently the brilliant Francis has had a severe psychotic episode and was only recently released into Leo’s care. Leo is torn between caring for his brother and winning the election. Smith and Marks’ performances are truly memorable.

Magaly Colimon plays Leo’s ruthless boss Carla with dominatrix zest. The role strains credibility in the first act, but becomes more clear in the second. The brilliantly understated James Sutorius portrays a rival spinmeister who’s at low ebb in his personal life. In masterful juxtaposition, Sutorius also plays Francis’ homeless buddy, named secretary of state by the delusional Francis, whose escape into the Lincolnesque is as pitiable and understandable as Parry’s in the 1992 film, “The Fisher King.” Lindsay Jones provides the stirring sound design. Michael Fagin’s scenic design is effective and imaginative. Anne Kennedy’s costumes and Chris Rynne’s lighting complete the portrait. New York director Joe Colarco makes an impressive Globe debut. 8-24-06

sdtheatresceene.com, Cuauhtémoc Q Kish – John Strands’ Lincolnesque seems to say that you can be anyone you invent, even if they cart you off to the loony bin. T. Ryder Smith (Francis) and Leo Marks (Leo/speechwriter) play two brothers who become players in “DC” politics. Although their forte is writing, it seems to underscore the fact that a good script (political speech) can boost not only ratings, but may even get the wrong candidate elected to pubic office. Francis is on outpatient status from Saint Elizabeth’s Hospital in the care of Leo, who tries his best to keep his bro on his meds, not always successfully. With or without meds, Francis has decided he’s the reincarnation of Abe Lincoln, reciting quotes from another era that underscore ideals rather than personal policy. The play shouts cynicism but is underscored throughout with the splendid words and phrases of Abe himself. Joe Calarco’s direction is spot on and allows all four actors to maximize their performances and they all maximize their moments on stage. Magaly Colimon (Carla) plays a hyper-bitch and executes her role with a high-octane take-no-prisoners attitude. James Sutorius plays the duel parts of Daly as well as the Secretary of War, characters from both ends of the political and monetary spectrum with aplomb and subtlety, getting good mileage from both roles. Smith is just about perfect as Lincoln/Francis, giving up moments of senatorial splendor and down-to-earth humanity while Marks plays the protective brother as well as the part is written. Perhaps the message in Lincolnesque is simply to look for guidance in the purity of words which can mark and define an individual and a universe. After all, it’s the words that speak to who we are, where our journey will take us, and who we touch along the way. 8-12-06

Gay/Lesbian Times, Jean Lowerison – Everybody wants something. Politicians in Washington, by and large, want prize, power and influence, and will do what they must to get and keep them. Speechwriter Leo (Leo Marks) is not much different from those pols. Employed at the moment by a hack Congress member, Leo wants to keep his job, which is to give the Congress member the words that will sway voters and keep him in office.

The only thing noble about this goal is that it will keep Leo off the street and allow him to keep an eye on his brother Francis (T. Ryder Smith), one of the most brilliant political strategists D.C. has ever seen, recently released from a mental hospital. Francis, you see, is convinced he is Abraham Lincoln (there is an unnerving physical resemblance), and runs around Washington reciting Lincoln’s speeches, which more often than not results in an encounter with the police. Leo’s candidate is down 10 points in the polls and a new team has been called in, headed by Carla (Magaly Colimon), an attractive but tough black woman who threatens Leo upfront, blaming him for the candidate’s slide. Meanwhile, Francis is doing well on medication; he’s befriended a homeless man he calls Stanton (Lincoln’s secretary of war, played by James Sutorius), and has even landed a job as a janitor. One night he is unknowingly befriended by Daly (the double-cast Sutorius), a campaign adviser for Leo’s adversary, who is impressed by Francis’ calm demeanor and intelligent words. The plot of this play, a world premiere by playwright John Strand, wanders a bit (the question is whether Francis can save Leo from the corruption of D.C. before it’s too late) and short-shrifts Carla by making her one-dimensionally hard-driving, but the idea is quirky enough to keep me engaged throughout. It’s interesting timing on the Old Globe’s part to schedule this play just as the 2006 political season begins to heat up. Lincolnesque is about power, integrity, greed, corruption and where these all fit into a political system often accused of favoring the rich and powerful rather than seeking to promote the public good. Today’s Washington, Leo tells us: “eats people. When people come here, they lose things … their brain, balls, integrity.” Marks’ well-meaning if easily seduced Leo is nicely played. Smith is properly enigmatic as Francis, who has either gone crazy or gone sane, depending on your perspective. Sutorius is excellent in his dual roles as Stanton and Daly. Colimon does what she can with her one-dimensional character. “The people hunger for heroes,” Francis says. I’m not sure we’re short of heroes, but we surely could use somebody Lincolnesque right about now.

[previous] [next]