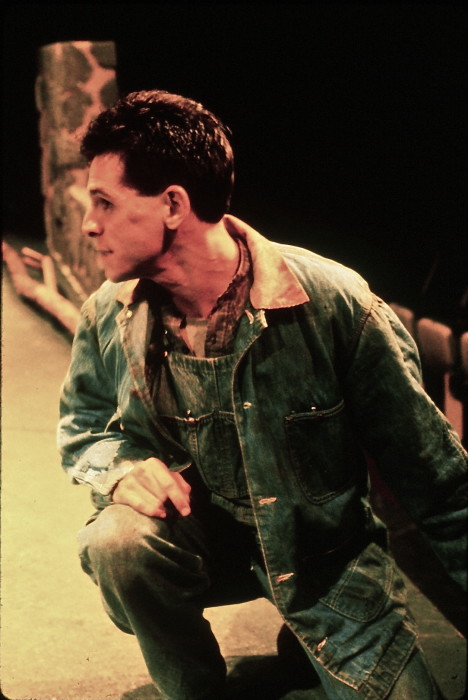

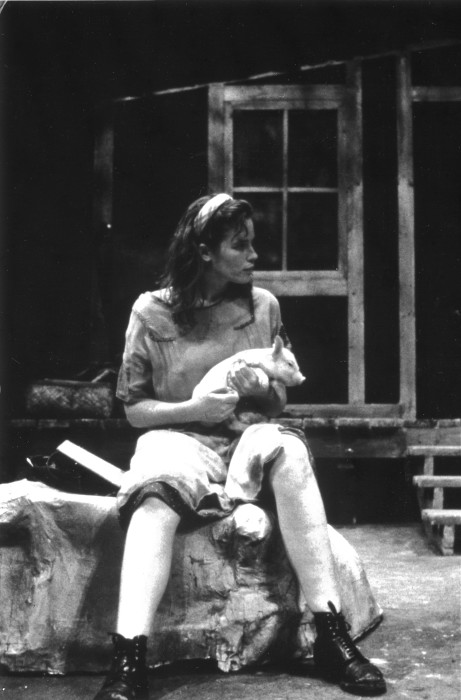

Above: T. Ryder Smith as Mike, Colleen Flynn-Lawson as Josie; Don Perkins as Hogan, Ed Dennehy as Tyrone.

Excerpts from the reviews

“This is the play Paul Barry was born to direct. It has awakened the poet in him, and he illuminates it’s every corner, brings out it’s every fluttering pulse. It is a tragicomic romance, a threnody, a black Irish folk ballad. . . .Without any seeming shifting of gears, these comic performances deepen into something tragic, then move beyond that to a transfiguring grace. Flynn-Lawson’s performance distills itself into a powerful simplicity . . . Wheezing, keening, Dennehy turns a dirty joke into a tragic song, decay into dark beauty. . . . And T. Ryder Smith deftly fields his brief scene as Josie’s brother. Bravo!”

– Bob Campbell, The Newark Star-Ledger

The Rake’s Progress

a tale for actors

The pig seemed like a good idea.

“A Moon for the Misbegotten” takes place on a farm, and the set for our production was realistic, beautifully so, a farmhouse, with real tree branches swaying above it – some 20-foot-long specimens donated by the local Parks Department – large heaps and scatters of actual, crunching leaves, refreshed daily from the copious amounts on the campus green, and a trickling creek. So why not an animal or two? Chickens were briefly considered, perhaps a dog, but the text refers to pigs . . .

A local farmer was contracted – he was a bit bewildered, having never leased out a pig before – and an infant sow was secured for the 4-week run of the show.

He was not only adorable when he arrived – a playful pink baby – but proved an excellent actor, nestling sleepily in the actress’ arms on his entrance, perking up at the appearance of the other characters, listening silently to their dialogue, and squealing cutely and very nearly on cue as carried offstage, to enthusiastic nightly applause, after which he trotted happily back to his offstage pen in the basement beneath the stage, where he slept quietly until the curtain call, where he was cheered.

None of us city folk, however, understood how rapidly pigs mature, nor could anyone have calculated what the effect might be for the actors and staff to constantly feed the pig treats as they passed by his little house next to the scene shop. He was tirelessly sociable, and always seemed hungry, after all, so why be bothered by that sign that said PLEASE DON’T FEED THE PIG?

And in addition to the food, who can say what dark magic all that cooing and petting had on fellow’s psyche. Plus the nightly applause.

Anyway, the pig grew. Fast. In all senses.

He started getting harder to catch in his pen as his entrance approached, heavier to carry up the stairs to backstage, and more difficult to handle once he was before the audience. He took to uttering short bleats and squeals between the actor’s lines. These ad-libs earned him a fair number of laughs, which seduced him into the fatal logic of all hams – sorry – thinking that more and bigger ad-libs would result in more and bigger laughs. And so the pig started to speak along with the actors, increasing his volume when they tried to talk over him. He complained as he was being carried off, and cried and whimpered long after his exit, his voice traveling up through the floor of the stage. He thrashed in his pen during the show, snorting at the voices above, eager for a larger role. The only way to keep him quiet was to feed him . . .

He stopped taking direction. His mood turned dark. He gained what seemed several pounds of brutal muscle a day.

By the 3rd week of the run he was a massive beast, kicking and spitting at the crew members trying to get him ready for his entrance, moaning and barking offstage, squealing throughout his scene, furious that his laughs had stopped, and then, for an exit flourish, releasing his bladder and bowels.

The director tried talking to him. The Stage Manager reasoned. The actors pleaded. But the pig only howled for his lost glory.

He was replaced by a rake.