photos by BW Productions

excerpts from the reviews

full reviews are below

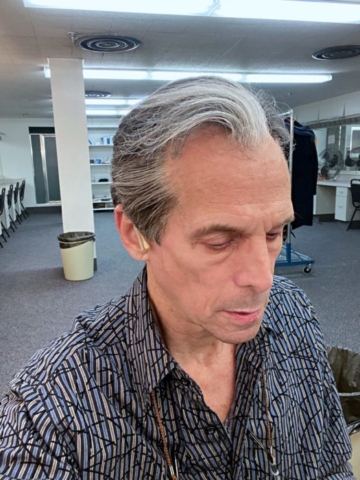

“Profoundly more relevant after our last 18 months of isolation, Pioneer Theatre Company returns by asking the hard questions and digging deep into family relationships (healthy and unhealthy) . . . The central figure of the play is Jule Waterman . . . an artist that uses a kind of visual synecdoche, seeing individuals in isolated pieces (body parts) that refer to their whole and creating art from those isolations. . . . Playwright Simon balances her story between fragmentation in not only relationships but in the scenes themselves. As an audience, we receive a portion of a scene, a snippet of conversation, then flit to another snippet of conversation. The result can be dizzying and there is a distinct sense that we are not seeing the whole picture – something that is indicative of the characters and their relationships. . . . Often, it is easy to watch a play and feel that we know the characters, but Simon doesn’t allow us to see all of them. They cannot be simplified; they refuse to be one-note or one-sided while they equally refuse to be seen in their totality. And this is not unlike real life and real relationships. . . . T. Ryder Smith (Jule) is Will’s father, a sickly narcissistic artistic genius, and Smith gives human depth and feeling to a character that could be played as a caricature in a lesser actor’s hands. . . . “

– Front Row Reviewers

“A sharply observed, intimate comedy . . . that explores the difficulties of living in the shadow of genius. . . . Playwright Ellen Simon took inspiration from her relationship with her famous, brilliant father, the playwright Neil Simon. Without writing a literal memoir, Simon [works] from often painful situations and emotions that clearly draw from her own life. . . . She is a sharp writer, with an ear for unforced dialogue that balances humor and emotional resonance. . . . [and] writes each member of this messed-up family with nuance—their motivations are transparent and human, even if they aren’t always exactly sympathetic. . . . As the play’s most important character, T. Ryder Smith gives one of the best performances I’ve seen onstage in a long time. You know that he’s, well, an ass, but crucially, his charm and magnetism shine through, too. It’s clear why the other characters can’t resist his gravitational pull—he has an easy chemistry with the other cast members that makes his obliviousness, and occasional outright cruelty, genuinely sting. Smith seems to relish the opportunity to play with the haughty persona of a capital-G Great Artist, and Simon subtly questions a culture that allows the powerful and famous to behave badly without impunity. . . . “

– Salt Lake Magazine

“Ass invites the audience into the intimacy of familial relations that have fizzled, that are strained, and that are somewhat dysfunctional. The greatest works can take an ordinary scenario and give the audience a glimpse of themselves, remind them that of the shared human condition, and that perhaps their woes are not so unique. But, Simon only managed to portray the mundanity of life without building a vested interest in the characters and their fate. . . . While I struggled to connect with most of the characters, Jule was written and acted splendidly.T. Ryder Smith gave a fabulously commanding and pompous air to Jule. Smith’s performance was funny because he was . . . developing the absurdity of the character . . . Smith was believable, dynamic, consistent, and entertaining. I especially enjoyed the aloof and bombastic dialect he cultivated for the character. Smith was also convincing as a man who was losing his abilities when work is the most important and static part of his life. “

– Utah Theatre Bloggers Association

“A witty, and touching play about family dynamics, estranged relationships, and of course, ass. . . . Speaks to the vulnerability we all carry within us, and the comfortability we have in showing it. It’s funny, yet it can also be sensual. Depending on the self-security of the person, it may be something that is easy to flaunt, while for others it is connected to the very sacred act of undressing. . . . A beautiful play, one that takes the absurdity of title and scenario in stride as it delivers a heart-felt tale.”

– Utah Daily Chronicle

offstage

full reviews

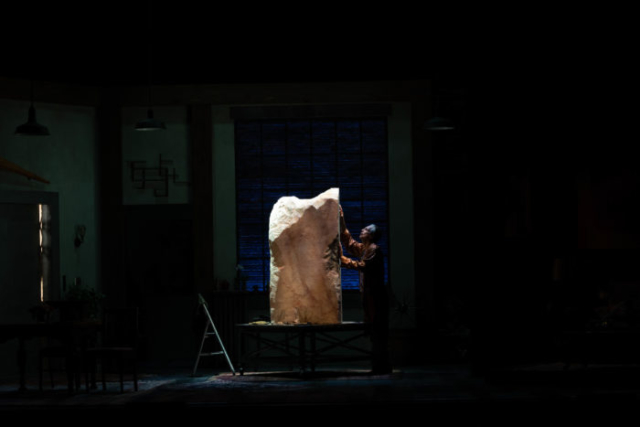

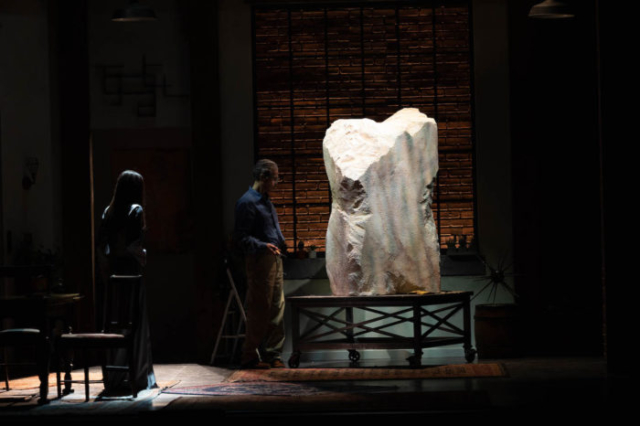

Front Row Reviewers, Jason and Alisha Hagey – Ass Poignantly Reiterates the Old Aphorism: Don’t Assume, or You’ll Make an Ass Out of U and Me – Profoundly more relevant after our last 18 months of isolation, Pioneer Theatre Company returns by asking the hard questions and digging deep into family relationships (healthy and unhealthy). In Ass we are given not just a tongue in cheek title referring to what is being formed out of the unrefined block of alabaster sitting in the middle of the stage (looming over us with the presence and ego of the artist), but also a humorous take on our own foibles and insecurities. The central figure of the play is Jule Waterman. Jule is an artist that uses a kind of visual synecdoche, seeing individuals in isolated pieces (body parts) that refer to their whole and creating art from those isolations. This is a purposeful choice on the part of Ellen Simon (Playwright) who said about her intentions for the play:

“I wanted to talk about parts vs. whole, to show how in relationships one can feel fragmented … what it’s like to be the offspring of a genius personality and what it means to feel whole.”

Simon balances her story between fragmentation in not only relationships but in the scenes themselves. As an audience, we receive a portion of a scene, a snippet of conversation, then flit to another snippet of conversation. The result can be dizzying and there is a distinct sense that we are not seeing the whole picture – something that is indicative of the characters and their relationships.

This concept plays into this idea of coexisting and the tragedy of not accepting both what is there and what is left unsaid and undone. Karen Azenberg (Director) said, “… It’s about expectations of family relationships. What does a child expect from a parent? What does a parent expect from an adult child? Can you get what you expect if you can’t ask for it, or if you don’t know how to articulate it or give it back?”

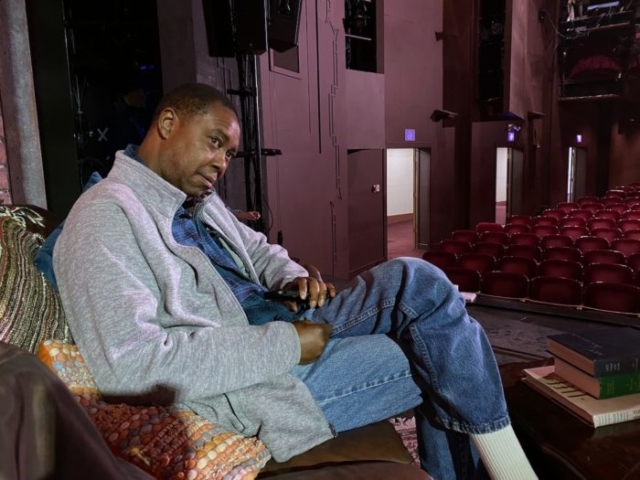

In need of a loan from his estranged father, Ben Cherry (Will) returns with his wife, Elizabeth Ramos (Ana), to his childhood home in New York City. Cherry and Ramos portray many dichotomies throughout the show: confident and unsure, supportive and pushy, warm and cold, etc. The roles are challenging. Cherry and Ramos come across as real as if we are voyeurs watching their lives, not seeing two actors on stage. T. Ryder Smith (Jule) is Will’s father, a sickly narcissistic artistic genius, and Smith gives human depth and feeling to a character that could be played as a caricature in a lesser actor’s hands. Laura Hall (Tory) is Jule’s wife and the dimensions of her performance keep you asking who this person is and how much are we like her?

Often, it is easy to watch a play and feel that we know the characters, but Simon doesn’t allow us to see all of them. They cannot be simplified; they refuse to be one-note or one-sided while they equally refuse to be seen in their totality. And this is not unlike real life and real relationships. We make assumptions from what we see and experience about an individual, but we only see pieces and therefore cannot and should not believe we know them as a whole. Thus, Simon is saying that we can never really know someone. In turn, she is asking, if we cannot really know someone, can we ever love them? In the end, we, like the characters of the play, do the best we can and continue to create and grow until we feel more whole.

The setting, on the other hand, is both simple and nuanced. Jo Winiarski (Scenic Designer) gives us an apartment in New York City and a dialysis center, transporting us into Jule’s world and the two main locations of his life. The realization of these settings feels authentic, like the characters’ lives, but leaves much out in a similar fragmentation. The alabaster monolith at the center is purposefully seen from the back, again hiding much of the ‘action’ yet ever-present. Paul Miller’s (Lighting Designer) use of light keeps us seeing the fragmentations, but never more powerfully than the fluctuating gobo that lights the monolith and subtly keeps a stagnant object moving, pulsating as if alive.

Ass reminds us to never mistake movement for progress. Though there are discussions and arguments throughout the play’s plot, it is hard to see any forward momentum by the end. Instead, Ass illuminates the reality that too much of life feels like it is alive but is really hardened and soulless in the end. The characters seek love in their relationships, but the refusal to see the whole of a person creates a world where they can never be fully understood much less loved. If we see others in fragments and pieces, can we ever really love them? If we show ourselves in only fragments and pieces to others, can we ever really be loved by them? Ass asks us to grapple with these questions and to come to our own conclusions about life, identity, love, and what it means to be alive. 10.23.21

–

Salt Lake Magazine, Josh Petersen – With a title that’s memorable, to-the-point and a little bit cheeky (sorry), Pioneer Theatre Company’s Ass is designed to grab your attention. Though the in-your-face title reminds you that you’re definitely not seeing Frozen (which is now playing downtown at Eccles Theatre BTW), Ellen Simon’s world premiere is not needlessly provocative, or even particularly crude. Instead, it’s a gently funny family drama that explores the difficulties of living in the shadow of genius.

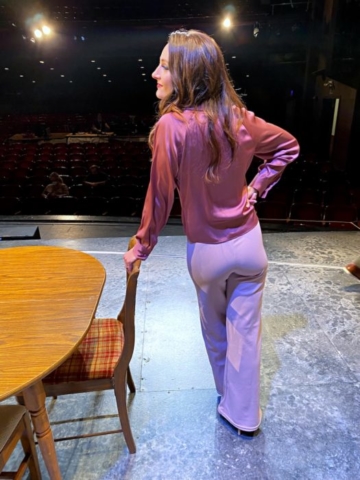

Jule (T. Ryder Smith) is a New York City sculptor known for his evocative depictions of single body parts (a big toe here, an ear there.) He is widely lauded as a genius, and he has the ego to match. He also has a strained relationship with his son Will (Ben Cherry), an art history professor who pointedly avoids studying the contemporary work his father creates. Will nervously travels to his father’s New York apartment with his bubbly wife Ana (Elizabeth Ramos) hoping to ask for financial help. The couple visits as Jule’s health is failing—while he waits for a kidney donation, he spends hours a week in dialysis with nurse Ray, (Vince McGill) who is refreshingly immune to Jule’s self-important posturing. As Jule struggles through treatment, his much younger ninth wife Tory (Laura J. Hall) obsessively monitors his health and finances as Jule slowly creates what may be his final work, a large alabaster sculpture of Tory’s ass.

Playwright Ellen Simon took inspiration from her relationship with her famous, brilliant father, the playwright Neil Simon. Without writing a literal memoir, Simon draws from often painful situations and emotions that clearly draw from her own life. This personal history is both intriguing and, from a creative standpoint, risky. In a narrative with significant parallels to her own life, Simon’s writing could have easily come across as navel-gazing, especially considering dysfunctional families and difficult artists are not exactly unique subject matter. Luckily, Simon avoids these potential pitfalls. She is a sharp writer, with an ear for unforced dialogue that balances humor and emotional resonance. Though Will appears to be the most direct stand-in for Simon, I never felt that she wanted to settle scores or stack the deck. She writes each member of this messed-up family with nuance—their motivations are transparent and human, even if they aren’t always exactly sympathetic. You probably don’t know what it’s like to live in the shadow of a father with sculptures in the MOMA, but the feelings of jealousy and betrayal that Will feels are relatable to pretty much anyone.

As the play’s most important character, Smith gives one of the best performances I’ve seen onstage in a long time. You know that he’s, well, an ass, but crucially, his charm and magnetism shine through too. It’s clear why the other characters can’t resist his gravitational pull—he has an easy chemistry with the other cast members that makes his obliviousness, and occasional outright cruelty, genuinely sting. Smith seems to relish the opportunity to play with the haughty persona of a capital-G Great Artist, and Simon subtly questions a culture that allows the powerful and famous to behave badly without impunity. (Jule is a womanizer with a taste for younger wives, but he is not an abuser or harasser. Still, the play’s exploration of great art made by much less great men feels especially relevant to modern debates about #MeToo and cancel culture.)

While Smith is a clear highlight, the entire cast gives wonderful performances. Led by director Karen Azenberg, who understands the play’s intimate scale, the cast keeps their work natural and human-scaled. The two women stand out in parts that easily could have faded into the background. Ramos is a warm, charming presence whose character has the unenviable task of tiptoeing around her in-laws from hell. Hall has fun with her role as a tightly wound WASP (or, as I couldn’t help whispering to my friend, a gaslight gatekeep girlboss) who Will derisively calls “number nine.” By the end of Ass she may be the least likable character, and Hall leans into her character’s narrow-minded desperation with dark humor and surprising physical comedy. As Jule’s most frequent victim, Cherry portrays the mixture of resentment and (usually unrequited) affection he feels toward his father. Jule is certainly not wrong to describe Will as “needy,” but I also rooted for him as he tried to break through the family’s dysfunction.

The play is less compelling when it moves away from the claustrophobic family dynamic. Ray, Jule’s nurse, is the play’s weakest character, though this is no fault of McGill, who gives a strong performance. The relationship between Ray and Jule becomes one of the most important in the play, but despite the actors’ best efforts, it never is clear exactly why these two characters have a strong impact on each other. Buried somewhere in their relationship is an interesting observation—Jule can only be emotionally intimate with Ray because there’s a clear power dynamic that he can control. Unfortunately, Ray is too thinly written for the friendship to register, and when Ray interacts with the rest of the family in the second act, he feels like a one-dimensional source of wisdom while the other characters are allowed more complexity.

Still, you shouldn’t miss this sharply observed, intimate comedy. Though Simon’s writing has a cynical streak, especially in the tartly funny first act, Ass is sentimental at its core. Even when the characters act selfishly, she never loses sight of their genuine desire for connection and the love, as messed up as it is, that binds them together. 10.29.21

–

Utah Theatre Bloggers Association, Alissa Frazier – Uneven Script Makes for a Flat Ass at Pioneer – What is the subject matter of a show called Ass? Who is the ass? Does it show an ass? Something to do with donkeys? While there were no nudity or animals, writer Ellen Simon’s world premiere does press viewers to assess which character is the Ass. The short answer is, perhaps all of them.

Ass invites the audience into the intimacy of familial relations that have fizzled, that are strained, and that are somewhat dysfunctional. The greatest works can take an ordinary scenario and give the audience a glimpse of themselves, remind them that of the shared human condition, and that perhaps their woes are not so unique. But, Simon only managed to portray the mundanity of life without building a vested interest in the characters and their fate. This Ass is flat.

Ass is principally about a father and son relationship. Will returns to his childhood apartment in New York City to see his father, a famous sculptor. Jule, the cantankerous egoist sculptor lives with his significantly younger ninth wife Tory and is in failing health. Jule is undergoing regular dialysis treatments and needs a kidney transplant to restore his quality of life. Will is broke after making a poor investment, and his spritely wife is struggling to conceive and needs expensive fertility treatments. The story follows the dance of the two men clearly desperately needing something that the other has to give but not willing to ask. As grandiosity meets mediocrity, Jule exhibits his greatness and the importance of his work while Will is fighting for his father’s approval and recognition.

Directed byKaren Azenberg. Ass had a saccharine start to the first act. The opening dialogue was unnatural, kitschy, and appropriate for a sitcom. From Ben Cherry’s heavy footed goofball portrayal of Will to Elizabeth Ramos’ over-eager and over-the-top Ana, there was a lack of sincerity for a play that should be a believable and intimate portrayal of a real-life family. Chemistry and timing were lacking, and the jokes were obvious and still failed to land.

The character of Tory (played by Laura J. Hall) was altogether confusing throughout the show, as she varied from blatantly sinister (in her threats to leave Jules) to attempted exaggerated silliness (in scenes such as when she was closing the hospital curtain mischievously while Jules and Will were having a discussion). The humor throughout felt forced and ill-timed and distracted from my ability to empathize with and connect to the characters.

While the shortcomings were a plenty, I do not blame the actors, as Simon’s script was weak, and perhaps Azenberg’s directorial choices exacerbated the weaknesses, rather than corrected them. To quote the play “life is so boring without tension,” and so was the first act.

Fortunately, the second act brought a less forced and more raw dialogue. I have seen Cherry perform at Pioneer before and have found him outstanding. Parts of the second act gave him an opportunity to showcase his talent and abandon the fluff. For example, in the scene that Cherry as Will describes riding the coattails of his father and using his father’s name to attain the only validation he has ever known, Cherry is impressive. Scenes such as this had the support of the script for the actors to give a genuine performance. As the writer Ellen Simon’s father is a distinguished playwright, I found the scenes with autobiographical implications, such as Wills turmoil, were written best and with the most sincerity.

While I struggled to connect with most of the characters, Jule was written and acted splendidly. T. Ryder Smith gave a fabulously commanding and pompous air to Jule. Smith’s performance was actually funny because he was not painfully hitting obvious humor again and again, but developing the absurdity of the character in such a way that it was comical. As Jule, Smith was believable, dynamic, consistent, and entertaining. I especially enjoyed the aloof and bombastic dialect Smith cultivated for the character. Smith was also convincing as a man who was losing his abilities when work is the most important and static part of his life. Additionally, Smith and Vince McGill as Ray (the dialysis nurse) had plausible conversations that were the most emotionally affecting, particularly when Ray tells Jule of his late son. I enjoyed the ironic bond between Jule and Ray as Jule fails to connect with his own son. But, regrettably, the shining moments of the second act were not enough to save the show.

My favorite thing about Pioneer Theatre Company is that they choose to do shows that other local companies do not perform, and they always have a superior quality in acting. I enjoy when they perform classics, and I have seen some tremendous contemporary plays at Pioneer. But Ass does not join the ranks of these productions. Nonetheless, I am pleased that we have a local company that takes the gamble and shows world premieres despite the occasional losing hand. If my criticism does not deter you from seeing Ass and you care to make your own opinion (as you should), note that the play does contain strong language and is not appropriate for young audiences. 10.24.21

–

Daily Utah Chronicle, Makena Reynolds – World Premiere is a Witty Play on Family Dynamics – Ass had its world premiere at Pioneer Theatre Company this past weekend. A witty, and touching play about family dynamics, estranged relationships, and of course, ass. Written byEllen Simon, Neil Simon’s daughter, and directed by Pioneer’s artistic director Karen Azenberg, the play was the perfect blend of sentimentality and sarcasm.

What is Ass?

The play follows Will (Ben Cherry) who comes home to visit his father, Jule (T. Ryder Smith) and his ninth and younger wife, Tory (Laura J. Hall). Jule is a famous artist, best known for his sculpting pieces that have been featured in the MOMA, and his current project pertains to a slab of alabaster that is destined to be carved into the bottom half of a woman.

As if living up to the expectations of his famous father wasn’t enough, it is quickly revealed through discussion with his own wife, Ana (Elizabeth Ramos), that an investment that he has made did not have the success rate that he intended which has left him broke.

Will hopes to ask his father for a loan, however, Jule is spending his time in dialysis treatment due to kidney failure. Will recognizes that to ask his father for twenty-thousand dollars while he is sick at the hospital “would kind of make him an ass.” It just so happens that Jule needs something from his son, that he is more than happy to pay for — his kidney.

The Heart of Ass

The connection between Jule and his dialysis nurse, Ray (Vince McGill) speaks volumes especially during a time when hospital workers are carrying the burden of a global pandemic. He is a strong, famous, and successful man with a harsh exterior, who has never asked anything of anyone.

As Ray states, a nurse’s job is to tend to all of the people and not play favorites and, in doing that, Jule finally feels seen. Jule even tells his son that he has acted like a “sycophant” and that he is just as guilty in the distance between the father and son.

This relationship between Ray and Jule is the heart of the show and, without Ray, there is no way that Jule would have ever been able to mend his relationship with his son.

Why the Title?

So why the title Ass? In a playwright’s note, Simon teases the viewer with various reasons she could have potentially chosen the absurd title. Personally, I feel as if Ass speaks to the vulnerability we all carry within us, and the comfortability we have in showing it. It’s funny, yet it can also be sensual.

Depending on the self-security of the person, it may be something that is easy to flaunt, while for others it is connected to the very sacred act of undressing. A character such as Tory is quite literally willing to bare her naked backside for the sake of a portrait, just as she has been open and vulnerable towards her husband. Whereas Jule, who struggles to chisel the ass in the alabaster, mirrors the struggle to connect with his son and family members.

It’s a beautiful play, one that takes the absurdity of title and scenario in stride as it delivers a heart-felt tale. 10.25.21

–

Utah Arts Review, Catherine Reese Newton – Ellen Simon Chisels Out a Witty Portrait of Family Conflict in Pioneer Theatre’s Ass – “Narcissism is the birthright of genius,” world-renowned sculptor Jule Waterman proclaims toward the end of Ellen Simon’s comedy Ass, which made its pandemic-delayed world premiere Friday night at Pioneer Memorial Theatre.

And Simon—herself the daughter of an artistic genius, the late playwright Neil Simon—does make some sharp observations about the ways in which we indulge the creative and famous.

But at bottom, this is a play about family and connection.

“The specifics have nothing to do with my family,” Simon explained an interview ahead of the show’s opening, “but when you sit and watch, you will get a little bit of what it felt like to be in my family.”

And indeed, the parent-child interactions in Ass, though hilariously heightened, are likely to feel at least somewhat familiar to anyone who sees the show.

World-renowned sculptor Jule Waterman, like the alabaster work-in-progress that dominates Jo Winiarski’s set design, is larger than life, and T. Ryder Smith luxuriates in the artist’s extravagant ego. “I am shaken to the core by my own brilliance,” he exults as he explains the inspiration behind his forthcoming masterpiece. Jule specializes in three-dimensional synecdoche, sculpting single body parts—an ear, a big toe, a neck—so masterfully that viewers can see the whole person.

But Jule’s son, Will, doesn’t feel wholly seen, despite having parts of his body immortalized in two of the world’s finest art museums. A financial emergency brings Will to his childhood home, but it quickly becomes clear that money is the least of the things he needs from his father.

Ben Cherry, last seen at PTC as an arrogant journalist in The Lifespan of a Fact, deftly reveals Will’s insecurity and resentment layer by layer, so that even when the character reaches peak unlikeability, we’re invested enough to forgive him.

Elizabeth Ramos plays Ana, Will’s wife, who does see him as a whole person and helps the audience to do the same. Her role is a less showy one, but Ramos invests it with warmth.

Vince McGill likewise brings emotional weight to Ray, Jule’s well-grounded dialysis nurse, who pushes Jule and Will to open up. Laura J. Hall plays Jule’s grasping trophy wife, Tory, with such verve that she’s a delight to watch despite the character’s breathtaking lack of self-awareness.

The pace relaxes occasionally as the characters achieve tiny epiphanies and moments of self-reflection, though Karen Azenberg’s direction is at its best when the banter is flying.

Simon’s witty script never feels self-conscious or sitcommy. this is a genuinely funny play in which all the jokes and one-liners arise organically from the characters. Almost all of these people behave in ways befitting the show’s title at some point (though none of them can outdo the audience member who took a phone call during Friday night’s premiere).

But they also reveal a humanity that renders them likable—or, in Tory’s case, almost likable. 10.23.21