Full review

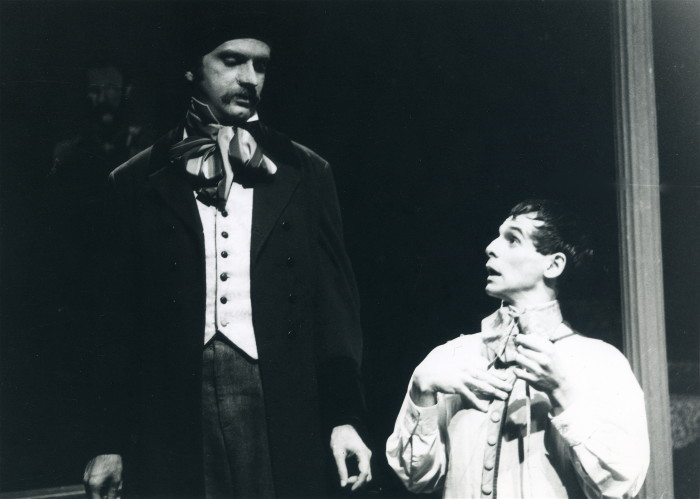

The New York Times, Wilborn Hampton – Everything One Might Want to Know About Nikolai Gogol – The stage has never been the most comfortable vehicle for biography, and the lives of writers, even great and eccentric ones like Nikolai Gogol, usually provide fairly flimsy material around which to build a drama. “Gogol”, a jumble of a play by Roderick O’Reilly that is being presented by the Beacon Project, is no exception. Certainly Gogol was an odd and troubled man. Vladimir Nabokov called him ”the strangest prose-poet Russia ever produced.” But bizarre behavior alone cannot support three hours of traffic on any stage, especially the crazy quilt Mr. O’Reilly has stitched together from Gogol’s writings, letters (mostly to his mother asking for money) and a lot of hearsay, the veracity of which is dubious at best. The play opens with Gogol on his deathbed, attended by a physician, who prescribes leeches and hot baths with simultaneous cold showers, and a mad monk of a priest, who counsels him to renounce everything in his life. The action then goes back to Gogol’s arrival in St. Petersburg at the age of 19 and proceeds chronologically, through 23 scenes, none notable for their brevity, ending up once again at the author’s deathbed, where he finally succumbs after burning the sequel to ”Dead Souls” to expiate his sins. Mr. O’Reilly seems to have tried to cram everything he has ever read by or about Gogol into his play rather than select representative moments to dramatize. As a result, the play is full of awkward transitions that leave the action darting incomprehensibly back and forth between Gogol’s work – particularly ”The Nose,” ”The Overcoat” and ”The Government Inspector” – and his life. When Pushkin dies, for example, Mr. O’Reilly transports Gogol, who was in Rome at the time, to the poet’s side. As Gogol cradles Pushkin’s head in his lap and reads him the first chapter of ”Dead Souls,” Pushkin looks up and mutters, ”One duel too many, eh, Nikolai?” Mr. O’Reilly further appears to take at face value Gogol’s later attempts to explain the symbolism that critics and the reading public had originally failed to see in both ”The Government Inspector” and ”Dead Souls.” But, as Nabokov noted, Gogol had a penchant for conveniently interpreting his works long after he had written them, and if Mr. O’Reilly’s version is to be believed, one is faced with the incredible prospect that one of history’s literary geniuses was little more than a religious fanatic who totally misunderstood his own life’s work. The Beacon cast only occasionally rises above the paucity of the material. Anthony John Lizzul, wearing a fake ski-nose that would be more appropriate for a Bob Hope impersonation, plays Gogol with such a zealous intensity one would never suspect him of ever having a sense of humor. Robert L. Rowe is the best of the ensemble, all of whom double or triple in various roles. Marc F. Nohe and Nancy Learmonth also have credible moments. The play moves very slowly in places, and Stuart Laurence’s direction does little to help one through the dull stretches. Elizabeth Huffman’s costumes are stunning. 4.14.90

[previous] [next]