Photo by Sara Krulwich

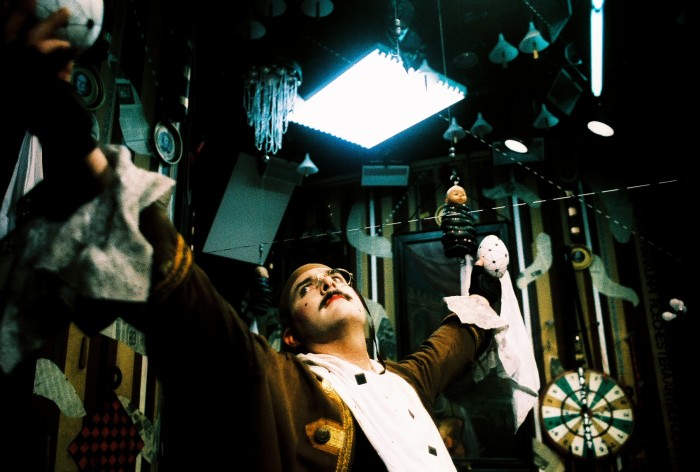

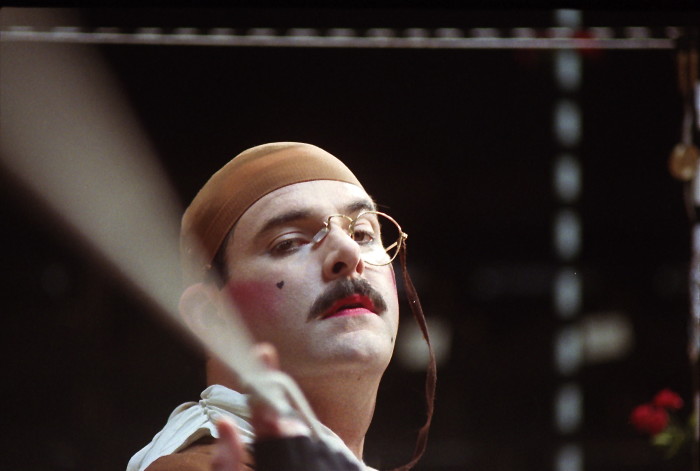

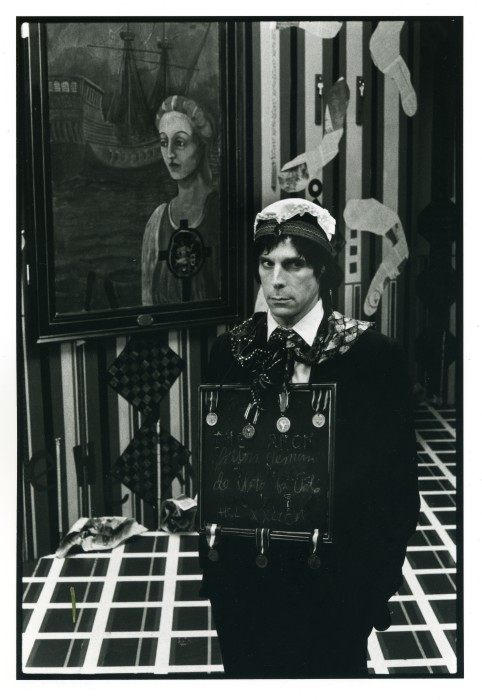

Photos by T. Ryder Smith/The Hinge Collective

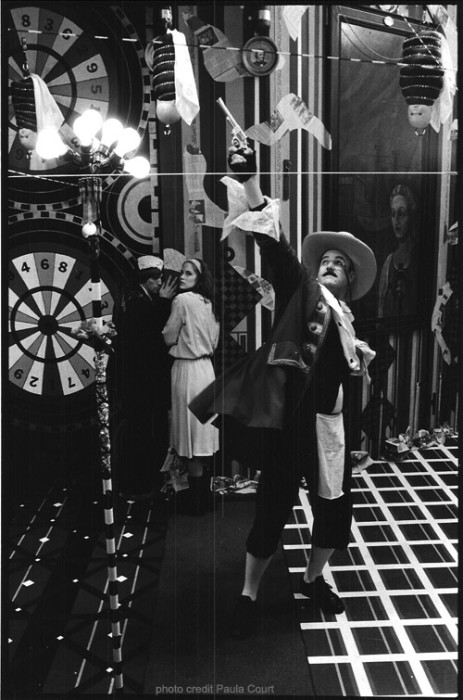

Above: photo by Paula Court

Above: screencaps from archival video

Excerpts from the reviews

Full reviews are below

“No U.S. president, I expect, will ever appoint a Secretary of the Imagination. But if such a cabinet post ever were created, and Richard Foreman weren’t immediately appointed to it, you’d know that the Republicans were in power . . . Rufus, who is and is not the President of the United States, is a cowboy who dreams of being king of the universe. Only, in the first instance, he isn’t really a cowboy, he’s a foppish English gentleman named Rufus who dreams of being ‘a real American cowboy’ . . . Jay Smith, a strapping actor, plays these moments, when Rufus is suddenly overtaken by his fop actuality, with a a hilarious dainty fastidiousness; it’s like watching Tom Mix suddenly acquire a consciousness of Proust. . . Foreman loves and pities Rufus as much as he despises and fears him . . . The whole [play] is a nightmare, much of which Foreman stages – between bursts of frenzied violence and slapstick – with a slow, dreamlike melancholy . . . Juliana Francis, as Susie Sitwell, has never seemed so wistfully vulnerable; unnerving in itself, her transformation enhances the show’s overall scariness . . . T. Ryder Smith [embodies] the Baron Herman De Voto with a slouching, rat-like charm, Pacino-ite diction, and a gift for deadpan comic timing that makes his the capstone of these three winning comic performances/ (I’ve been going about the house for days now, trying to duplicate the way he says “Crete’ – just the one word – without cracking up: I can’t.) . . . The wonder is that a work so filled with hilarity should leave, as it’s last impression, such an overarching sense of anguish.” Michael Feingold, The Village Voice

“‘Rufus’ is a symbol of imperialism gone made . . . It is ultimately about our inability to ‘wake up’ – as an offstage voice (Foreman’s own) repeatedly commands us to do. The play is one of the most overtly political of Foreman’s recent works, but he balances it’s didacticism with a mordant wit.” Hilton Als, The New Yorker

“The staging is beyond fault, as are the highly disciplined, spookily silly performers . . . No one is better than Mr. Foreman at creating the sense of a confounding universe out of joint and on a slick road to nowhere.” Ben Brantley, The New York Times

Video

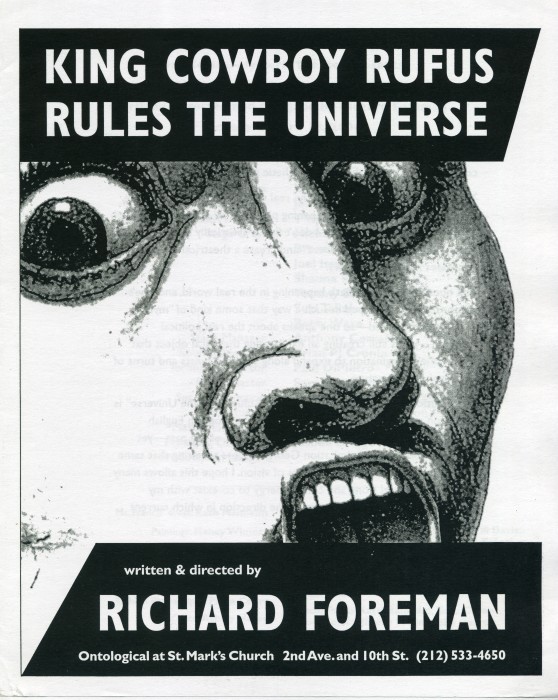

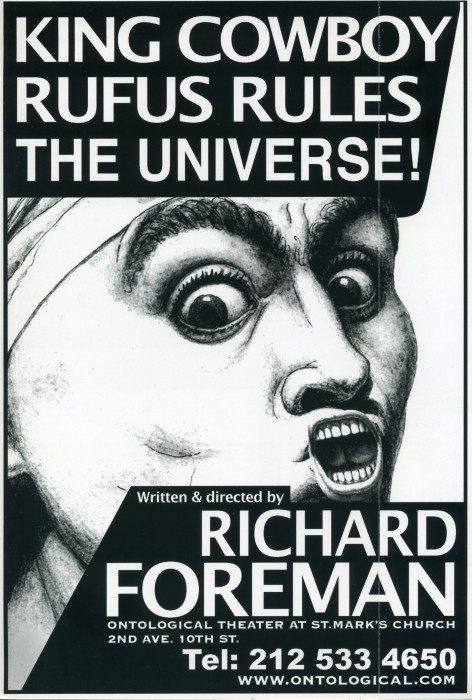

Publicity

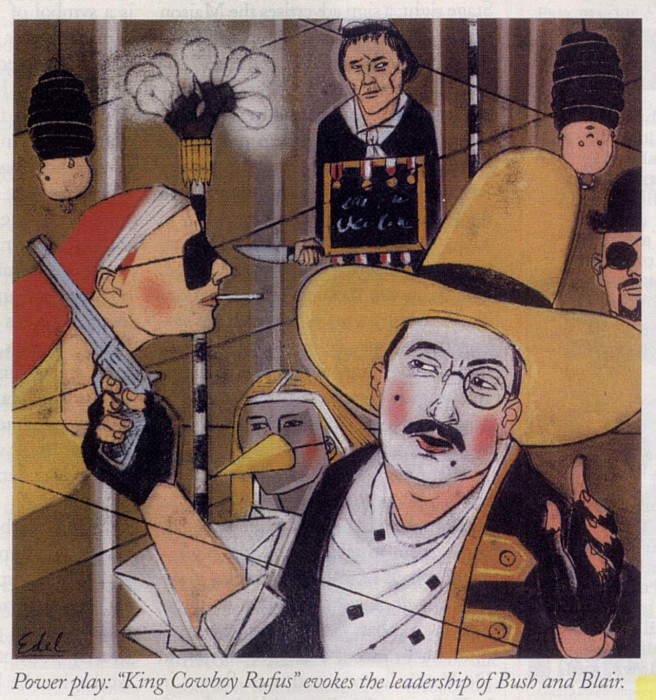

Above: New Yorker magazine cartoon.

Offstage

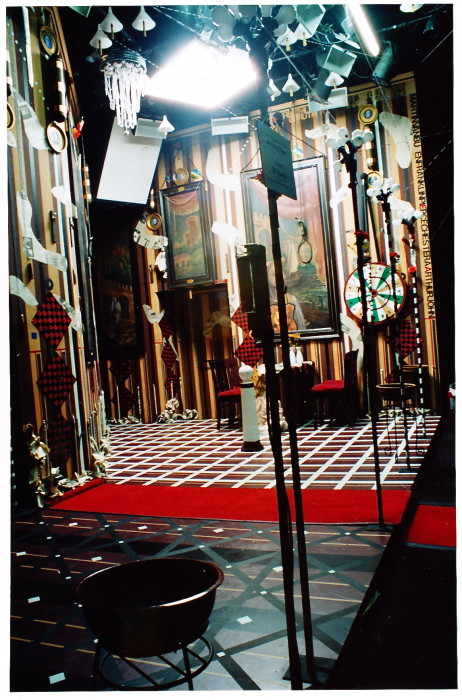

From top: details of the set, the set, Richard’s control board.

Richard Foreman. Photo by T. Ryder Smith.

Above, closing night, in back: Joshua Briggs, Anthony Cerrato, Richard Foreman, Paul Di Pietro, Michelle Diaz , Julian Francis, Jay Smith, Suzi Takahashi, Joel Israel. In front: T. Ryder Smith, Brenda Hattingh, Shauna Kelly, Tommy Smith.

Full reviews

Village Voice, Michael Feingold – Foreman’s Wake-Up Call. No U.S. president, I expect, will ever appoint a Secretary of the Imagination. But if such a cabinet post ever were created, and Richard Foreman weren’t immediately appointed to it, you’d know that the Republicans were in power. Republicans don’t believe in the imagination, partly because so few of them have one, but mostly because it gets in the way of their chosen work, which is to destroy the human race and the planet. Human beings, who have imaginations, can see a recipe for disaster in the making; Republicans, whose goal in life is to profit from disaster and who don’t give a hoot about human beings, either can’t or won’t. Which is why I personally think they should be exterminated before they cause any more harm.

This opinion is presumably not shared by Foreman; you can gauge the breadth of his imaginative compassion from his willingness to extend it even toward George W. Bush, idiot scion of a genetically criminal family that should have been sterilized three generations ago. The hero of Foreman’s new play, who is and is not the president of the United States, is a cowboy who dreams of being king of the universe. Only, in the first instance, he isn’t really a cowboy—he’s “a foppish English gentleman” named Rufus who dreams of being a “real American cowboy”; his dreams of being King Cowboy of the Universe are always being brought up short, during the work’s giddy 80 minutes, by his awareness of this inherent falsity in his role. Waving and wildly discharging his giant six-shooter, Rufus invades the audience, drives his supporting cast off the stage, and revels in absolute power. But, as is customary in Foreman’s deceitful universe, something always arrives to trip him up; often enough, it’s his own self-doubt. Jay Smith, a strapping actor, plays these moments, when Rufus is suddenly overtaken by his fop actuality, with a hilarious dainty fastidiousness; it’s like watching Tom Mix suddenly acquire a consciousness of Proust.

Clearly, Foreman loves and pities Rufus as much as he despises and fears him; Rufus is a part of him as Bush is a part of us. The whole thing is a nightmare, much of which Foreman stages—between bursts of frenzied violence and slapstick—with a slow, dreamlike melancholy. “Wake up,” Foreman’s standard vox ex machina keeps urging his characters. The call’s reinforced by Susie Sitwell (Juliana Francis), Rufus’s female opponent, goad, and temptation. Invited to sing something “uplifting,” she responds with a few bars of “When the Red Red Robin Comes Bob Bob Bobbin’ Along,” but gets stuck on the phrase “wake up” in the lyric, repeating it with the pallid helplessness of the Little Match Girl hawking her wares on the snowy streets. Francis, whose angular beauty and lively presence usually bring her more acute-minded roles, has never seemed so wistfully vulnerable; unnerving in itself, her transformation enhances the show’s overall scariness. Full of character interactions and budding twigs of plot, the work feels more like a conventional play—probably something post-Chekhovian—than anything Foreman’s done in years.

It isn’t one, of course. The air of surrender may be everywhere, even on the aesthetic front, but Foreman’s no defeatist. In addition to Susie, Rufus has a male rival, alternately accomplice and opponent, The Baron Herman De Voto, embodied by T. Ryder Smith with a slouching, rat-like charm, Pacino-ite diction, and a gift for deadpan comic timing that makes his the capstone of these three winning comic performances. (I’ve been going about the house for days now, trying to duplicate the way he says “Crete”—just the one word—without cracking up; I can’t.) The Baron owns a cigarette factory, shuttered by the economic downturn, where Susie works as a “coquette.” (Shades of Carmen.) Rufus contemplates buying the factory, thinking ownership would entitle him to “dalliance” with Susie and her fellow “strangely attractive female employees, whom, I believe, are never disinclined to such adventurism.” (The line perfectly conveys the Edwardian tea-party language into which Rufus is constantly lapsing.)

Like most of Rufus’s attempts at adventure, this one either goes haywire or gets deflected; Rufus’s attention span is no more reliable than his diction. Not for him the tragedy of Don José. Girls, antagonists, business, the astonishments of the universe —nothing can get in the way of this fake cowboy’s dreams of glory. Even the end of the play is so contaminated by Rufus’s ego that Foreman has to go to extraordinary lengths, in the show’s last outrageous laugh, to keep it from infecting the curtain call. In a remarkably explicit program note, Foreman explains, for the first time in my experience, his authorial intentions. “I hope,” he says, that the play’s fictional devices “allow many levels of theatrical irony and comic energy to coexist with my anguished point of view concerning the direction in which current American policy is leading us.” Rest assured, Richard, your hope is fulfilled. The wonder is that a work so filled with hilarity should leave, as its last impression, such an overarching sense of anguish. 1-21-04

The New Yorker, Hilton Als – The Big Roundup: Richard Foreman takes on the ghosts of imperialism. Before the vital and brilliant American playwright and director Richard Foreman found a permanent home for his Ontological-Hysteric Theater, at St. Mark’s Church, in 1992, you had to seek out his annual productions in small, experimental venues around town. I first went to one of Foreman’s plays, “Eddie Goes to Poetry City: Part 2,” at La Mama in 1991. I had never seen anything like it before, and haven’t seen anything comparable since. By then, I’d already heard about Foreman; I knew that he not only had been writing, directing, and designing his own plays since 1968 but also had directed works by Brecht and Molière, here and abroad, and staged a number of operas, ranging from Johann Strauss to Philip Glass. Still, nothing had prepared me for the darkness and the dazzle-the murky splendor-of “Eddie.” A kind of Cubist “Candide” that evoked the wretchedness of desire, the play infiltrated my thoughts until its actors and its dialogue began to feel like figments of my own imagination, suddenly made real in my poetry city, New York.

Eddie, a sweet, open-faced naïf, was a poet-Christ figure, wandering through a corrupt metropolis where a series of hardboiled female characters tried to lure him down the slippery, sexy path to wisdom. And yet he remained largely incorruptible. The cynicism he encountered was as baffling to him as the lipsticked sirens whose movements were choreographed to entice him. At some point, his good-natured optimism began to feel almost as grotesque and willful as the temptations of the villains around him. To tell Eddie’s story, Foreman eschewed the conventional dramatic devices of exposition, motivation, and resolution in linear time and space. Throwing Aristotle out, he ushered the subconscious in. His dialogue was full of the hilarious slips of the tongue and double entendres of daily life that allow our sentiments, as well as our nightmares, to seep to the surface. In an essay in his 1992 collection, “Unbalancing Acts: Foundations for a Theater,” Foreman explained his artistic intent this way: “Society teaches us to represent our lives to ourselves within the framework of a current narrative, but beneath that conditioning we feel our lives as a series of multidirectional impulses and collisions.” He went on, “I like to think of my plays as an hour and a half in which you see the world through a special pair of eyeglasses. These glasses may not block out all narrative coherence, but they magnify so many other aspects of experience that you simply lose interest in trying to hold on to narrative coherence, and instead, allow yourself to become absorbed in the moment-by-moment representation of psychic freedom.”

In short, Foreman is a poetic realist. The psychic freedom in his work grows, oddly, out of his fixed obsessions-namely, female sexuality (he generally views women as dangerous, conniving, alluring vamps) and his own Jewishness. Foreman has described himself as a “closet religious writer,” and many of the stage sets he designs contain symbols from Jewish mysticism, which serve as talismans of his faith and of what that faith has generated in him: a spirit of inquiry, skepticism, and hope. Foreman’s casts always include at least one character-usually male-who appears as the Semitic model of disbelief.

In his latest work, “King Cowboy Rufus Rules the Universe!,” that character is given the rather stolid yet florid name of Baron Herman De Voto (played by the versatile T. Ryder Smith). At the beginning of the play, De Voto, dressed like an errant rabbi in a dark suit and a stiff black wig, renounces his ownership of a tobacco factory, which, it seems, is the source of all social evil. Sitting at a table, facing the audience, De Voto intones in the snidest of voices, “Thank God I am closing down my dilapidated tobacco factory-stuffed full of coquettes and whores. I’ve had enough of this shit world in which I find myself.” This is Krazy Kat by way of Spengler-a distinctly Yiddish locution with a nasty street snarl, which tips De Voto into a defensive kind of despair. De Voto serves as a sort of alter ego for Foreman-the critic in the playwright’s mind, the character who doubts the artistic process even as he becomes an integral part of it. With his deadpan face and conservative gestures, De Voto is the heckler at the back of the class. In this case, the classroom is the world. And the world is an outgrowth of Foreman’s distinctive visual imagination.

The stage at St. Mark’s is relatively small-it measures twenty-eight feet across-but Foreman floods it with information. Stage left: oil paintings in fake-gilt frames show women in Renaissance dress, standing by canals. Stage right: a sign advertises the Maison Rouge, a cathouse. At the front of the stage, facing the audience, Foreman has placed four poles, each holding a cluster of light bulbs that give off a migraine-inducing glare. Above the center of the stage, a row of fluorescent lights flicker. As the director Peter Sellars points out in the foreword to “Unbalancing Acts,” in a Richard Foreman production, “There are messages written all over the set. . . . The lights are flashing because, in our lives, the lights are flashing. Are we getting the signals . . . or are we going to shut our eyes until it’s all over? Are we able to gaze steadily into the source of brightest light? At what point does it become too painful?”

Part of what makes Foreman’s characters feel like apparitions-figures who, in the midst of a hideous, cluttered landscape, seem to take in nothing at all-is their lack of response to the glare. Light is as natural to them as darkness is to a bat. At least, Susie Sitwell (Juliana Francis), a former worker at De Voto’s factory, seems to flower in it. Delivering her lines with the flat affect of a lobotomized but naughty ingénue, doused in L’Air du Temps and intelligence-her sharp, stilted movements recall those of Oliver Sacks’s “sleeping” patients in the film “Awakenings”-Susie is looking for a new boss, a new man, a new hero, to take De Voto’s place. (Without a man, she makes clear, her existence as a self-described “coquette” would be meaningless.) The man she needs appears almost at once: King Cowboy Rufus (the gifted Jay Smith), who decides to buy the tobacco factory. Wearing a ten-gallon hat and an eighteenth-century frock coat, his lips and face rouged and powdered beyond anything Beau Brummell could have imagined, his belly jiggling over his sheepskin chaps, Rufus stalks the small stage with aplomb. This is his world, he seems to be saying; we’re just living in it. “Are you really an American cowboy hero?” Susie asks him. “Or rather-an old-fashioned English fop harboring impossible dreams of glory?” Well, Rufus is a bit of both. And why not? Isn’t this make-believe?

It is, and it isn’t. Rufus’s will to power-like that of the world leaders he evokes, George W. Bush and Tony Blair-is as real as he is invented. Rufus is a symbol of imperialism gone mad. “I’m no traitor. And I’ll prove it easily with my subsequent violent behavior,” he announces. He has “family values”-dolls descend from the ceiling whenever he needs to prove that he loves children-but what do those values mean when the very heart of his quest is to suppress and destroy anything that contradicts his own reality? “Recently I find myself performing random acts that just bounce back and forth inside my head like a ferocious game of Cowboy Ping-Pong,” he says, after firing his gun at Susie and trying to strangle De Voto. In the unexplained mayhem that follows, the characters are blindfolded and left to stumble around the stage and slit their throats, in a kind of hell of their own making.

“King Cowboy Rufus Rules the Universe!” is, ultimately, about our inability to “wake up”-as an offstage voice (Foreman’s own) repeatedly commands us to do. The play is one of the most overtly political of Foreman’s recent works, but he balances its didacticism with a mordant wit. At the end of the show, the supporting cast carry globes onstage for Rufus’s target practice, but he is stymied: he can’t choose which world, which reality, to destroy first. “King Cowboy Rufus” echoes the past (from time to time we hear a voice counting in German, punctuating the dialogue). But history, Foreman implies, is what we’re done with; now we must make our way, through the blinding lights of CNN and other forms of propaganda, into an unbrave new world. 1-26-04

New York Times, Ben Brantley – Richard Foreman’s Foray Into Politics. Something hard and noisy is hammering at the door of Richard Foreman’s dream world. And Mr. Foreman, the avant-garde magician famous for keeping his plays hermetically sealed, has been obliged to let the intruder in. Yes, political reality has stuck its sharp, bony head into the metaphysical puzzles and swirling illusions of Foreman Land in the shape of a would-be cowboy king with dreams of a globe-spanning empire.

This high-aspiring, dimwitted and exceedingly dangerous fellow — whose role model just happens to be the sitting American president — is the title character in ”King Cowboy Rufus Rules the Universe,” which opened last night at St. Mark’s Church in the East Village, where Mr. Foreman annually stages peerless miniextravaganzas for his Ontological-Hysteric Theater. As is customary for this director, ”King Cowboy” is a dazzling mind tease, replete with images that somehow seem to have originated in your own head.

Yet while the production offers the dizzy theatrical joys expected of Mr. Foreman, the light of his polemical anger shows chinks in his mise-en-scène. Visually, ”King Cowboy” is as rich as any Foreman production in recent years, transforming the tiny St. Mark’s stage into a labyrinthine and lavish cultural scrapheap. But it seldom hijacks your senses the way Mr. Foreman’s work usually does.

Rufus, played in grandly effete style by Jay Smith, is definitely not your standard-issue Wild West hero. He dresses like a Restoration fop, handkerchief fluttering from sleeve, and speaks in a tonier-than-thou English drawl. But oh, how he would love to fill a 10-gallon hat and wield a six-shooter to bring the world to its knees.

Amid exchanges of dislocated dialogue with his adversarial companions — a Humphrey Bogart-like nobleman (T. Ryder Smith) and a coquette with the voice of a Bouvier sister (Juliana Francis) — Rufus lusts after crowns and globes that intermittently dangle from above. Of course, he always wants the largest of these. And the mere prospect of violence both races and quells his dandy’s heart.

Most of the stylistic Foreman signatures are in place here: the cross-cultural medley of musical fragments; the strings and poles that segment the stage; vulnerable baby dolls and menacing thugs in animal outfits (this time, bears instead of gorillas); the chorus of sinister functionaries in internationally eclectic attire. (As Diana Vreeland might have said, why not top your kilt with a tailored evening jacket and black cowboy hat?)

Nowhere to be seen, though, is the pane of plastic that has traditionally separated Mr. Foreman’s audiences from the stage. Its absence allows Rufus to walk up the aisle to survey his domain, ”primed and ready to fulfill my every desire,” as he puts it. The implicit message is that it is now impossible — or at least irresponsible — to isolate art from life. The same idea comes across in words chanted again and again by Ms. Francis and by Mr. Foreman, in electronic voiceover: ”Wake up.”

The script for ”King Cowboy” is more verbose and less cryptic than usual for Mr. Foreman, although those unfamiliar with his work will no doubt still be at sea. And since a program note makes it clear that the play is a response to the politics of George W. Bush, you find yourself listening for direct topical references.

They’re definitely there but rendered in poetic Foremanspeak. ”Rhyme things that don’t rhyme,” Rufus says. ”You understand — words don’t come easily to someone trying to be an all-powerful American cowboy.” Ms. Francis exclaims, ”Oh, frigid man — I recognize the sneer inside the cowboy voice.” And there are many passages in which Rufus is more and more megalomaniacal.

Some of this is pretty funny. But Mr. Foreman’s strength as a writer has always been his refusal to spell anything out. His scripts are most often made up of tantalizing, repeated non sequiturs that assume different meanings as you listen. ”King Cowboy” is weighed down by literal-minded allegory, and you rarely surrender yourself to the phantasmagoria, as you long to.

That said, the staging itself is beyond fault, as are the highly disciplined, spookily silly performers. (I also enjoyed the Lewis Carroll-style songs.) No one is better than Mr. Foreman at creating the sense of a confounding universe out of joint and on a slick road to nowhere. That’s the sense of the world a lot of people have these days. Paradoxically, Mr. Foreman’s vision would feel far more relevant without the political footnotes. 1-16-04

Time Out NY, David Cote – It may surprise anyone who has followed Richard Foreman only recently that his new work addresses issues of American imperialism (explicitly) and the Bush administration (implicitly). But actually, the cryptic avant-gardist has trained his sights on the Oval Office before. In his 1988 coproduction with the Wooster Group, Symphony of Rats, Foreman cast the late, great Ron Vawter as an existentially challenged President whose consciousness is fractured by messages from outer space, robots and sinister advisers. A similar absurd tweaking of the executive branch takes place in King Cowboy Rufus Rules the Universe!, in which a monocled and handkerchief-waving English fop aches to become “a real American cowboy.”

Foreman cleverly conflates the conflicting roles of cowboy (solitary outlaw) and king (courtly lawgiver) in the title character, who is played with perfectly balanced comic gusto by Jay Smith. Although Rufus’s plummy accent and effete tendencies make him an unlikely allegorization of Bush, remember that our plainspoken Prez is a millionaire blue blood.

Rufus is shadowed—and manipulated—by two other figures, a businessman-mobster called the Baron (T. Ryder Smith) and the seductress Susie (Francis). Because Foreman writes, directs, designs and controls all aspects of his shows, critics rarely write about how crucial his casting is. Here, the two Smiths and Francis have wonderfully good chemistry. Rufus also benefits from a vigorous and—dare I say—empathetic protagonist, who grounds Foreman’s surreal staging with unusual humanity. He’s still monstrous, firing his pistol and lisping about heroism, but he’s also quite funny and pathetic. That’s due in part to Jay Smith’s performance. But don’t forget we’re in the playground of a master showman, so expect flashing lights, eerie music loops, ominous voiceovers and the disorienting effects that Foreman has honed for decades, and which he now uses to express his political horror.

CurtainUp, Les Gutman – Ordinarily, Richard Foreman’s plays bombard us with a grab bag of impressions to sort out afterwards. At their best, they implant footprints on our thought processes. In King Cowboy Rufus, we are again left with much to ponder, but the playwright/director’s program notes uncharacteristically reveal his (not terribly well-disguised anyway) aim quite explicitly: “to put on stage, not George Bush himself, but a foppish English gentleman who, while seeming a figure from out of the past–yet dreams of becoming an imitation George Bush–acquiring that same power and manifesting similar limits of vision.”

Thus venturing into the miasma of the current political environment, Foreman is sensitive to the risk of doing nothing more than “preaching to the converted”. Yet it’s unlikely his annual, eagerly-anticipated East Village exercise will attract many of the unwashed, and so we must consider how it functions, or could function, as political theater. In the final analysis, though it displays its auteur’s signature artistic vision beautifully, it fails to do the one thing it must: incite its audience to action.

The play employs the standard Foreman-esque imagery and techniques (discussed ad nauseam in previous reviews which are linked below and thus not repeated here), but with his target identified, the shards on display here add up to more than they usually do — markers on a path already cleared rather than detours on a road to some truth. Ironically, perhaps, in being so explained, they rob the audience of the heavy-lifting which Foreman trained us to do long ago, and which, in Foreman’s very best works, is rewarded with even more trenchant truths. The story, it would seem, does indeed hide those truths.

Foreman may also have met his match in GWB. Who could invent a fiction to compete with the contemporaneous news: a president who, while riding huge deficits like a bucking bronco, announces a plan to occupy the moon as a stepping stone to conquering Mars? How could Rufus (Jay Smith), who merely trains his six-shooters on every empire in sight, trump that?

Smith manages to invest Rufus with affectations so perfect that they simultaneously feel both genuine and absurd: part monster, with a Texas-size appetite for everything from crowns to countries, part pathetic soul and much of the remainder, spoiled child. He is joined by a remarkably gifted pair of actors for his romps: T. Ryder Smith, who portrays Rufus’ compadre, The Baron Herman De Voto, as if he were Humphrey Bogart portraying a sardonic Rasputin, and Juliana Francis as Susie Sitwell, described repeatedly as a coquette and acting like every woman that description conjures up. Flawless execution is a Foreman trademark, and this trio is more than up to the task as he leads them (and the seven members of his “stage crew”) through his kaleidoscope effortlessly.

No one will be disappointed by the exhibition of Foreman’s work in Rufus. And no one has the right to demand anything more of his efforts. But knowing the stakes, and having undertaken to explore them, for Foreman to have done more would have been welcome.1-16-04

hotreview.org, Jonathan Kalb – The Madness of King Rufus.When Thomas Jefferson opined that no president could ever do irrevocable harm to America’s democracy in only four years, he had clearly not counted on George W. Bush. By the same token, when Richard Foreman conceived his Ontological-Hysteric Theatre as a manic, carnivalesque projection of his mental interior, he had clearly not counted on the ability of a real-life warmongering cowboy-poseur like Bush to threaten his creative repose. In an atypically self-justifying program note to King Cowboy Rufus Rules the Universe, his latest Ontological-Hysteric Theatre production, Foreman says the work is atypically political: “the pressure of the real world is such that I feel the need to respond to what’s happening.” Actually, the piece is no more or less political than half a dozen others he has done over the years responding with exquisite subtlety and complexity to public issues from Watergate to the end of Communism to Monicagate. Something in the nature of this particular political moment, however–its virulence, its doublespeak, its trivializations–has compelled Foreman to reach further than he has before towards a certain overtness that jangles a bit with his idiom.

The title character of King Cowboy Rufus–a rotund and ridiculously pretentious fop played with marvelous egomaniacal relish by Jay Smith–is an old-world English gentleman who dreams of becoming a “real American cowboy hero.” He is variously described as a man to whom “words don’t come easily,” “a man who works like a horse and then–sleeps like a big, fat, dirty log,” and “a man who claims he has no desire to leave his own neighborhood.” In case you don’t get the cryptic Bush references, the cluttered saloon-cum-French-cabaret set is festooned with portraits and names of American presidents, as well as the usual bric-a-brac from Foreman’s personal collective unconscious: checkerboards, striped strings, antique dolls, torn newspapers, Hebrew letters, roulette wheels.

In some of his maddening plays, Foreman does provide a fairly lucid story arc for his central character–or at least a more discernible one than he gives here. This, however, is one of those works that seems to loop around on itself like a helix of absurd and outrageous activities. Rufus buys an abandoned tobacco factory in the hopes of a “dalliance with [its] unhealthy yet strangely attractive female employees”; declares that he has “no imagination” and complains when forced to use what he has; poses with babies who look like fat larvae popping out of black cocoons; shoots pistols for no reason; eats “crow pie”; has his head sliced open by foils who say he is “hard to penetrate”; and suffers innumerable other bouts of humiliation, self-doubt, bewilderment and frenzy. Near the end, as a sort of afterthought, he mentions that he’d like to rule the universe.

His foils are a brooding, occasionally snappish “coquette” named Suzie Sitwell (played with lugubrious seductiveness by Juliana Francis in a beige silk dress) and a poetry-mangling, poker-faced aristocrat from Crete named Baron Herman De Voto (T. Ryder Smith, sporting a thick Brooklyn accent, fuzzy pink slippers and a chalkboard with indecipherable writing over a blue business suit). The chief function of these others–along with a chorus of kilt-clad young men and fishnet-clad cigarette girls–is apparently to keep Rufus off balance in his quest for theatrical self-confidence and hence sexual and political power.

From just this sketchy description, it should be clear that King Cowboy Rufus is a bona fide labyrinthine Ontological-Hysteric Theatre work, not some simplified reversion to political didacticism or, worse, Cartesian logic. All the Bush references are really false limbs, because no Foreman character is ever consistently or straightforwardly allegorical–including those he has occasionally named after historical figures like Friedrich Nietzsche and George Bataille. Foreman’s characters are always personifications of the phases of his mental anguish. That’s what he means when he says he does theater not just in a different style but for different reasons from other people.

Thus, if he sticks to his general working method, he can’t be didactic because, advocacy aside, he’s not even asking (as most playwrights are) to be seen as a font of anything (sagacious precepts, moving homilies, clever quips). His plays are vessels for anguished reverie, meticulously guided disorientation–his own and ours. If specific worldly associations distract in any way from this larger attempt to disorient, it’s because they are indeed less interesting than the more freewheeling process of distraction he’s famous for. Like all regular Foreman-goers, I’m used to taking fantastic mental side trips during his plays. This time, however, I found that those trips took me farther afield (I was stuck for long intervals on Iraq, terrorism and the Patriot Act, for instance) and often kept me from the marvelous serendipitous returns to his imagistic smorgasbord that I’ve come to cherish.

Perhaps sensing this danger of distraction from distraction, Foreman has enlisted his actors to draw us repeatedly back into his world. There is no plexiglass in front of the stage for this show, for instance, and Rufus enters the audience several times along a red carpet up the center aisle, scattering enough spittle and perspiration to rouse a slumbering Republican: “Look at . . . me–way up here, from the vantage point of honest to God, ordinary Human Beings, just like you and you and you–and me. Join me? YIP YIP YIP! GET ALONG LITTLE DOGGIES.” On top of this, asides and other confidences to the audience are more explicit than they have been in many years, particularly from the Baron.

All of this really amounts to adjustment rather than radical departure for Foreman, though, whose whole career could be described as an exploration of the extent to which interiority can be invaded by external events before it loses its brilliance and mystery. As he once wrote apropos Symphony of Rats, another play about the President of the United States (originally done with The Wooster Group, in 1988): “The real politics of America have to do with the conflict between people who can sustain ambiguity in their lives, and people who are terrified by ambiguity and fight to reduce every issue to clearly defined choices, either black or white, and so become conservative reactionaries. All my plays engage exactly this issue–how to sustain ambiguity in your conscious life without allowing it to plunge you into feelings of loss and confusion.” To me, these explorations have almost always been splendidly audacious, inspiringly weird, and consummately political, even at their most hermetic. Perhaps this time a need to join the political fray cost Foreman a measure of the disorienting concentration that he knows so well.

Offoffoff.com, Joseph Langham – Send in the crowns. Richard Foreman’s latest raucous creation, “King Cowboy Rufus Rules the Universe,” lets you seek out your own meaning in it, but makes no secret of its relevance to the reign of our present-day clown prince.

My, what a big hat. It sets at an odd angle atop a rather odd, effete and large man who is speaking with a drawn out royal accent to an odd, yet seemingly smaller man wearing a chalk board that speaks in classic, yet rhythmic Brooklynese as they are both in adoration of a lovely lass, who speaks… very… deliber..ate…ly. Sound strange? It is! Who is this Rufus? Is he cowboy, or is he fop? Is he just another John Wayne in Malvolio’s clothing? What power does he crave? Does the Baron stand in his way, or is he somehow a co-conspirator helping him to achieve his lofty goals? What does Susie have to do with anything? These are some of the many questions left deftly unanswered by the great, inimitable, Mr. Richard Foreman. How on earth is one to review such madness? Why is there no entry for “madness” in the thesaurus? Why will this word occur so oft in this review? These are questions left unanswered by a rather unworthy reviewer.

Let us start with a general description of the evening denying any temptation to get, shall we say, avant-reviewish. When we walk into the famed Ontological-Hysteric Theater we are greeted by a line of people, who like us, wish they had arrived much earlier. Alas, we have not, and everyone seems a little tense in getting a seat. Silly Americans, not everything is about you, you, you. And so, we, we, we take our seats and proceed to enjoy ourselves quite immensely and at times quite fanatically. The set is pure bright madness with ropes, classical paintings, kooky splashes of clashing colors, and a mass assortment of odds and ends dangling dangerously from the ceiling. It is, perhaps, comparable to “Alice in Wonderland” with no Alice and no Wonderland. First, the audience is greeted by The Baron Herman De Voto, the deadpan owner of a soon to be defunct cigarrette factory. He introduces us to Susie Sitwell whom he would like to attempt the old blindfold, cigarette and knife trick. He rares back, knife in hand and decides against it. These first few moments set the pace of the evening and let us know that we are in for an extremely bizarre ride full of, yes, you guessed it, madness. Then, in ambles King Cowboy Rufus. Oh, and the glorious, revolutionary mayhem ensues…

There is at this particular point in a review such as this, an enticement to attempt to interpret the hidden message of such a quirky play. To attempt such an interpretation would be, to put it bluntly, wrong. To say what one feels each character and their actions represent, would serve only to take this opportunity away from a prospective audience member. So at that we will leave any interpretations up to you. And you should definitely go see it. And you should spend hours with your friends picking it apart. What fun!

The bleedingly obvious character reference and one that is touted in the program and on the website is that King Cowboy Rufus is an artistic typification of the greed that lies deep within the leader of our current administration. In his artist’s statement in the program, Foreman says, “But though I am anti-Bush and anti-war — I don’t find it artistically satisfactory to simply ‘preach to the converted’ and create a theatrical diatribe that expresses my political views.” In all honesty, it might have been a stronger choice to leave any statement of what this play is or isn’t out of the artist’s statement, and let the ideas expressed live freely to be deciphered as they may. While it is fun for many of the “converted” to laugh at Boy Bush, perhaps if all Bush references had been left out of printed materials, some of the “non-converted” would have attended the show, and said to themselves, “Holy crap, I think I voted for that guy.” But then again, they might well have said, “I like this Rufus fellow. That man is a born leader.”

Aside from any program/promotional criticism, this play was an absolute delectable delight. Never did the action falter, never did the set or sound design fail to entice, and never did the performances of the talented cast and capable stage crew waiver. T Ryder Smith’s portrayal of The Baron Herman De Voto, was hilariously simple and extraordinarily level-headed in its focus. He was like The Fonz on 50 doses of Valium. This understated performance paved a clear path for Jay Smith’s beautifully contradictory way-far-over-the-top King Cowboy Rufus. One of the biggest laughs of the evening came when The Baron hollowly says, “Use your imagination.” and Rufus painfully proclaims, “I don’t have one.” Juliana Francis as Susie Sitwell turned in a performance filled with a nice range of emotions and quite the lovely singing voice. Her deliberate speech and pace set up many a joke such as, “My name… is Susie… Sitwell.” to which Rufus replies, waving his hanky, “Oh, and you do. You do.”

In case you don’t know already, Richard Foreman is legendary. He has won many awards, written and directed a ton of plays, and has understandably had books written about him. This play is deliriously fun and manages to remain poignant without smacking you over the head with anything but wacky madness and brutal impetuosity. While this is the first Foreman play that this reviewer has seen, it most certainly won’t be the last. You should go see this one. If you can’t see this one, see the next one titled “The Gods: When Does the Movie Start?” slated for Late Summer/Fall/Winter 2004. If you live this life without seeing a play by this national treasure, you, poor soul, have cheated yourself. 2-3-04

NY Theatre Wire, Glen Loney -Richard Foreman’s Annual Jewel-Box-Prettified Iconical Theatricals are always something very special in the way of integrated stage & costume-design, archly overacted performance-style, bizarrely bold lighting-effects, and darkly mysterious symbols of strange demonic passions & possessions.

Ontological-Hysterical productions seldom reverberate with resonances with the World of Reality as most audiences experience it. But this winter Foreman has imagined and realized a sort of Political Satire as a salute to the run-up to the 2004 Presidental Election.

Jay Smith—as the effete, Restoration-Foppish King Cowboy—may well be intended as an outrageous parody of the Cowboy From Crawford, shooting off his six-guns & his mouth at any target in sight. But he’s actually much more like a much earlier Bluster-Prone President, the Rough-Rider, Strenuous-Lifer, Teddy Roosevelt. As a nightmarish vision of Presidential Power gone berserk, however, this show will surely delight both Bush Haters and lovers of Avant-Garde Experiments as well.

Nonetheless, it’s a safe bet Pres. Geo. W. Bush would never recognize himself in King Cowboy Rufus. It’s an even safer bet that VP Dick Cheney—hiding in a secret undisclosed [redundant] location—would never permit him to enter the tiny attic-theatre in historic St. Mark’s-in-the Bouwerie. After all, Peter Stuyvesant’s ghost still haunts the church-yard!

From time to time, it’s an interesting respite to move one’s dazzled eyes from the intensely & intricately decorated stage-setting and manic acting to Richard Foreman himself. He sits unsmiling in the front-row at a tiny control-board, intently watching everything in action. His virtually unchanging expression betrays no reaction to what he sees & hears. His mini-control-board may well be a symbol of his puppet-master production techniques, for Foreman is Avant-Garde Theatre’s Arch Control-Freak. With always interesting & glittering & baffling results…

The Brooklyn Rail, David Kilpatrick – Foreman Gets Political. Since last year, when King Cowboy Rufus Rules the Universe was announced as the title for Richard Foreman’s 2004 production, rumors flew that he was going to— at long last— give us a “political” play.

Given the Bush administration’s utter disregard for truth and justice, there should be no shortage of artists raising their voices in opposition to the plethora of abuses at home and abroad. But from the celebrated godfather of the American theatrical avant-garde, a shift towards the political suggests a new direction.

Foreman’s work first appeared amidst the turbulence of 1968; however, unlike other artists active at the time, he never engaged in agitprop, his work presenting an alternative to the hippie ideals of environmental or communal theatre. His plays have never been tied down to messages or concerns that become irrelevant. Indeed, the idea of a unified point-of-view simply doesn’t gel with Foreman’s unique theatrical vision. While sustaining and furthering a distinctive style, his plays remain fresh, never an exercise in topical repetition or nostalgia.

For those who make the pilgrimage to St. Mark’s Church for their annual dose of Ontological-Hysteric Theater, such rumors were unnerving: would this mean there would suddenly be some lesson we should learn?

Any concerns that Rufus marks a departure of style or approach prove unfounded. While those looking for laughs at G.W.B.’s expense might well be satisfied, the closest reference to the production of W.M.D.’s is a tobacco factory, which the titular protagonist buys from his friend The Baron Herman De Voto.

Foreman has always been blessed with bold and brilliant actors to wrestle with his words and images, and this cast is stellar. Jay Smith is larger-than-life as Rufus, played as an English “fop,” more Scarlet Pimpernel than Buffalo Bill; through an overly refined Oxbridge accent he shares his fantasies of being a “real American hero,” with a ten-gallon hat and a six-shooter for fetish objects. Rufus buys the tobacco factory to exploit the vulnerability of Susie Sitwell, the “beautiful coquette” with a similar English accent, played by Juliana Francis.

Both performers are welcome returns to the Ontological, while T. Ryder Smith (terrific as Warhol to Francis’s Valerie Solanas in last summer’s overlooked Tragedy in 9 Lives at P.S. 122) rounds off the speaking cast (supplemented by Foreman’s standard silent chorus of stagehands), playing the Baron as a world-weary tough-guy, his accent reminiscent of a film noir gangster, a private eye or some Bogart blend of the two.

The Baron would be the sole “real” American of the three, were it not for his claim to be from Cyprus. He says that Rufus is just an “imitation” cowboy, but goes on to proclaim him “President of the United States.” Images of former Presidents and their names incorporated into the set design reinforce the connection between the ambitions of the imitation cowboy and the presidency. Having imagined himself the cowboy hero, Rufus uses the idea of being President to allow himself dreams of universal domination, though what he’d do with such power we can only fear. With demands like, “rhyme things that do not rhyme,” we are much more likely to laugh.

Other stage business (e.g. the appearance of a giant crow pie and ithyphallic bears wielding swords) reminds us that, after all, it is only theatre, and Foreman would never encourage any suspension of our disbelief.

Still, the timeliness of this work should not be underestimated, as we know full well how the real imitation cowboy threatens our place in the universe. Behind its hilarity, Rufus is the most political statement Foreman has ever made, and perhaps his most American work, powerfully exploring the mythology of our imaginary community. It takes a figure such as Rufus to make Bush II believable.

To be sure, Foreman’s program note makes clear his “anguished point of view concerning the direction in which current American policy is leading us.” It was obvious that the vast majority of the audience shared in this anguish, for the collective disgust at cowboys that would rule promoted a sense of camaraderie among the audience that was rather atypical at the Ontological.

I can’t imagine many compassionate conservatives will attend, but if they do, it is difficult to determine what they would make of such a work. As obvious as the connection between Rufus and Bush is, Foreman’s avoidance of blatant ideology makes the play a hard target for those on the right who fight the culture wars, and one wonders if they know or care about this particular battlefield.

It is doubtful that Rufus will provoke them, just as it is far fetched to think it will change anyone’s political sensibilities. It is more likely that others will criticize Foreman for not being more overt, more direct in condemning the decidedly unfunny antics of King Cowboy Bush.

But Foreman’s artistry has never been about placing theatre in service of some didactic mission. And as loud as we laugh (more often individually than collectively), Foreman’s plays have never really been about entertainment. Instead, they are platforms for the exploration of consciousness, and as timely as Rufus is, that remains the primary concern of the Ontological-Hysteric Theater. So while King Cowboy Rufus Rules the Universe does not mark any stylistic departure, it does afford a glimpse of how our current political crisis affects the mind.

[previous] [next]