Photos by Joan Marcus

Excerpts from the reviews

See full reviews below

“Transfixing . . . has the gripping intensity of a thriller . . . Hall has an assured sense of dramatic pacing, an ability to evoke a foreign culture with vivid specificity, and an unusual affinity for subject matter that blends history and mystery . . . Directed with equal measures of sensitivity and theatrical flair by Michael Greif . . . The acting is across-the-board superb.” Charles Isherwood, The New York Times

The most important new play of the year to date . . . A tightly written play that places a chokehold on your attention right from the opening line. . . . Part of what makes “Our Lady of Kibeho” so impressive is that Ms. Hall circumvents all kinds of possible dramaturgical pitfalls along the way. . , . The play has a political background, one that [Hall] sketches with crisp efficiency—but “Our Lady of Kibeho” never turns into a rant. . . . The most interesting performance is, not surprisingly, elicited by the most interesting character. Father Flavia (T. Ryder Smith) is an investigative priest dispatched from Rome by the Holy See to determine whether [the girls] are anything more than hysterical teenagers. Having exposed a few too many phony miracles for his soul’s good, he has become a doubter in spite of himself . . . Mr. Smith gets him so right that you’ll be thrilled by the soft-spoken subtlety of his impersonation. . . . One hell of an exciting show.” Terry Teachout, The Wall Street Journal

“Katori Hall is emerging as a major American voice . . . With the support of Michael Grief, she has produced a show which balances the poetic with the grotesque as beautifully as she balances the comedic with the sad . . . Father Flavia (the wonderful T. Ryder Smith) . . “ The New Yorker

“Thrilling . . . There are 15 very fine actors in Michael Greif’s sterling production at the Signature and moments of wonderful stagecraft, including a breathtaking Act I finale. (The second act draws gasps of its own, notably when a world-wearied Vatican investigator, played by the invaluable T. Ryder Smith, interrogates the girls.) . . . It resounds beyond its own plot; questions of poverty, sexism and interethnic tension echo throughout the story. Hall’s passionate play renews belief in what theater can do: It awakens you into a trance.” Adam Feldman, Time Out New York

“Michael Greif has been far too indulgent of both the playwright’s directorial demands and the performers’ overblown acting. An audience should never be too far ahead of the story or of character development. But we are, and it’s a chore to sit through the repetitive scenes of schoolgirl hysteria and adult foolishness.” Marilyn Stasio, Variety

“A gripping drama, tautly staged. . . . Hall manages to make the play feel both like a keen documentary and a rippingly good mystery . . . Greif has gotten superb performances from the company . . . As the papal representative, T. Ryder Smith’s work has a continental flair, a healthy sense of world-weariness, and, most important, an air of genuine religious commitment to it. . . . Theatre-going of the highest order.” Andy Propst, American Theatre Web

“A complex drama that explores how individuals, groups and countries deal with moral, economic and political repercussions of such events. . . . The excellent performances from the multi-tasking ensemble as well as the actors in the pivotal roles make Ms. Hall’s play as entertaining as it is challenging. . . . T. Ryder Smith is a source of both scary high drama and wry humor as Father Flavia, the representative sent by the Vatican to test the validity of the girls’ visions. . . . Director Michael Greif has given Ms. Hall’s mesmerizing, multi-faceted play the deluxe production it deserves.” Elyse Sommer, Curtain Up

Offstage

Black Lives Matter.

At the end of the curtain call on the evening of the Eric Garner decision, our cast raised hands in solidarity with the ongoing protests against police violence.

We collectively continued the gesture at the end of each performance through closing night. Many members of the audience responded in kind.

Curtain call photos by Dante Sully.

On the night of the Eric Garner decision, the cast meets at intermission to discuss possible responses.

Our cast, top, and below, the cast of “Father Comes Home from the Wars”, running concurrent with us at the Public Theatre.

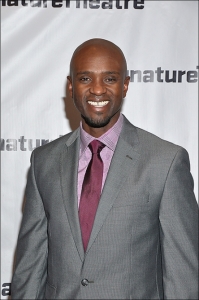

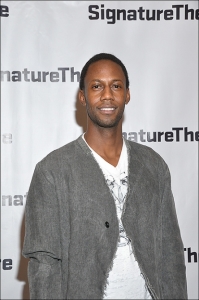

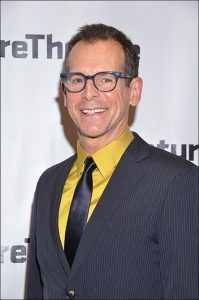

Cast members Owiso Odera, Stacy Sargeant, T. Ryder Smith, after a preview performance.

T. Ryder Smith and Wendell Pierce, after a performance, closing weekend.

(See “Waiting for Godot” page here.)

Opening night.

L to R: Brent Jennings, Irungu Mutu, Kambi Gathesha, Mandi Masden, Owiso Odera, Bowman Wright,

Niles Fitch, T. Ryder Smith.

Opening night.

Almost the full cast. L to R, back: Brent Jennings, Irungu Mutu, Kambi Gathesha, Owiso Odera, Bowman Wright,

T. Ryder Smith, Nneka Okafor.

Front: Niles Fitch, Mandi Masden, Jade Eshete, Joaquina Kalukango, Danaya Esperanza, Angel Uwamahoro.

Opening night portraits.

Row 1: Director Michael Greif and playwright Katori Hall, Nneka Okafor.

Row 2: Owiso Odera. Jade Eshete.

Row 3: Joaquina Kalukango, Irungu Mutu.

Row 4: Danaya Esperanza, Kambi Gathesha

Row 5: T. Ryder Smith, Mandi Masden

Row 6: Stacey Sargeant, Niles Fitch.

Row 7: Angel Uwamahoro, Brent Jennings.

Portraits above by Playbill.com.

A post-show talkback. Katori Hall with mic.

Photo above by The Hinge Collective

See also: The Moth and the Flame. Inadvertent cast reunion here.

Rehearsal

Above:

Row 1: Katori Hall talks with Angel Uwamahoro; Michael Greif discusses a note with Owiso; set model.

Row 2: Set going up; Danaya Esperanza; Stacey Sargeant.

Row 3: Owiso Odera; the girl’s makeshift shrine; the “schoolgirl trinity”.

Row 4: Waiting during tech: Mandi Masden, Niles Fitch, Kambi Gathesha.

Row 5: Angel Umamahoro; in the dorm; teching the opening scene, Nneka Okafor on right.

R0w 6: First image of show; Nneka talks with Owiso; notes from Michael.

Row 7: Teching video; the girls are visited; prior to levitation.

Row 8: The levitation, from backstage.

A photographic experiment

The play was set in the early 1980’s and my character used a camera in one scene, so of course the prop was a vintage camera. I tried taking some photos during rehearsal, using my iphone to shoot through the lens of the old camera. Some of the results are below.

Backstage

Above:

Row 1: in the dressing room; Bowman Wright and Irungu Mutu; Kambi talks with one of the company managers.

Row 2: getting into Villager costumes; Niles Fitch.

Row 3: Kambi Gathesha; Stacey Sargeant; Irungu Mutu with sound engineer.

Row 4: Stage managers Michael McGoff and Winnie Lok; Owiso Odera with company manager.

Row 5: Irungu practices mandolin; backstage video monitor; crucifixes in sunlight.

Row 6: Props.

Row 7: Bowman Wright’s character took a polaroid photo during a scene in the show: some of the ghostly results.

Row 8: Details of Rachel Hauck’s exceptional set; good advice, backstage and in life.

Publicity

Reviews

New York Times, Charles Isherwood – Mysteries of Heaven and Earth. The teenage girl, a young 17, seems incapable of deception. Her voice rises into a bright squeal when she becomes excited. Her eyes have a limpid clarity that suggests no subterfuge. She is docile and abashed by authority, even though her bubbly nature keeps her long, elegant limbs in constant nervous motion. She doesn’t even wear shoes.

And yet the claims of Alphonsine (Nneka Okafor) are outlandish, even in the setting of a Catholic girls school. She says she sees visions of the Virgin Mary, who speaks to her when she is in a trance, filling her spirit with both joy and fear, and telling of events Alphonsine cannot possibly otherwise know.

“Our Lady of Kibeho,” a transfixing new play by Katori Hall that opened on Sunday night at the Signature Theater, explores the turbulent ramifications of Alphonsine’s visions as other girls begin experiencing them, and news of the phenomenon spreads beyond the school into the Rwandan village of the title, in 1981 and 1982. The play has the gripping intensity of a thriller, in part because pricking at the edge of our consciousness throughout is the knowledge of the horror that engulfed the country a little more than a decade after the events in the play take place.

Ms. Hall, the author of “Hurt Village” and “Children of Killers,” about the survivors of the Rwanda genocide, has an assured sense of dramatic pacing, an ability to evoke a foreign culture with vivid specificity, and an unusual affinity for subject matter that blends history and mystery. (“The Mountaintop,” her somewhat hokey Broadway play about the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., had a supernatural element.) The events depicted in “Our Lady of Kibeho” actually took place, although Ms. Hall has taken some license to stoke the dramatic fires.

Father Tuyishime (Owiso Odera), the priest who runs the school, and Sister Evangelique (Starla Benford), the head nun, try to quash Alphonsine’s excited talk of her visions. They are worried that the school will come under scrutiny, and their fears are eventually realized.

He’s more sympathetic, assuming that Alphonsine is just a devout girl carried away by her enthusiasm, and the heat. While he gives her some light punishment for telling her “tall tales,” he also cannot help asking if, in these supposed visions of hers, the Virgin was “muzungu” — meaning white.

The more stern Sister Angelique seethes with outrage, and enlists Marie- Claire (Joaquina Kalukango), a leader of the girls — partly through her seniority, at 21 — to help quell these blasphemous doings. Sister Angelique encourages Marie-Claire to pinch Alphonsine when she falls into one of her trances, and later to burn her with a candle if that doesn’t work.

Coloring their reactions to Alphonsine’s claims are the deep-rooted divisions in the culture that, when they crop up in the dialogue, send shivers down the spine. Alphonsine is a Tutsi; Sister Angelique a Hutu. “Tutsis lie,” says one of the girls who follow the lead of Marie-Claire, as they harass Alphonsine. “That’s what my ma said.” Alphonsine’s bitter retort: “Well, maybe that is proof that Hutus lie.”

Shortly after this tart exchange, Alphonsine falls into another trance, sliding to her knees and lifting her arms in a gesture suggesting a radiant embrace. Ms. Okafor’s extraordinary transformation, from a defensive schoolgirl one moment to a mute, enraptured figure who almost seems to glow with spiritual radiance, has an arresting authenticity.

As the other girls watch in fascination or fear or scorn – or all three – suddenly one of them, Anathalie (Mandi Masden), also swoons into a trance, to the horror of the others, and the outrage of Marie-Claire in particular. “Come back,” she insists, as Anathalie seems to be transported, neither seeing nor hearing.

“Our Lady of Kibeho” may at first seem to be a study in the contagion of religious mania and its ability to take hold in deeply religious or superstitious cultures. Eventually, a third girl begins seeing visions, and as news of this spreads, the town and eventually the country boil with excitement. But both the play and the production, directed with equal measures of sensitivity and theatrical flair by Michael Greif, favor a sympathetic, not to say credulous, view of the events.

Father Flavia (T. Ryder Smith), an emissary from the Vatican, arrives to authenticate or discredit the girls as “visionaries.” He is skeptical, or maybe just racist. He finds it unlikely that the Virgin Mary would appear to girls in “the jungle,” as he describes Rwanda, to Father Tuyishime’s seething anger. “There is a saying in our country,” he says proudly. “Rwanda is so beautiful that even God goes on vacation here.” (That’s another moment that chills.)

Father Flavia tests the girls’ knowledge of scripture — apparently the Virgin Mary only appears to A students — and is inclined to be dismissive until suddenly Anathalie begins speaking to him in fluent Italian, referring eerily to events in his own past. (We witness a feat right out of a horror movie that would tend to support the girls’ visitations.)

The acting is across-the-board superb. Ms. Okafor’s gentle-spirited Alphonsine and Ms. Masden’s more starchy Anathalie are delicately etched portraits of girls who are at once young for their age and, as they come under fire, quickly gain emotional maturity. Ms. Kalakungo is also terrific as Marie- Claire, whose antipathy takes a surprising turn. As Sister Evangelique, Ms. Benford brims with righteous fury at what she sees as mere witchcraft, but eventually we watch in sympathy as her own spiritual foundation is shaken; there’s some envy in her anger at the girls. Why them, God, and not her?

Both as written and directed, with special effects by Greg Meeh, “Our Lady of Kibeho” all but affirms the reality of the girls’ experience. But even if, after the play has finished, you return to your comfortable skepticism, as you watch it Ms. Hall’s drama has an eerie fascination. Suspending our disbelief for a while is among the primal pleasures of theatergoing. Here it is thoroughly enjoyable, at least until the girls’ visions turn dark, when it becomes deeply disturbing. 11.16.14

The New Yorker – With her ninth full-length play, the thirty-three-year-old writer Katori Hall is emerging as a major American voice. Set in Rwanda in 1981, the play covers a year in the lives of several girls at a Catholic school in the beautiful, segregated village of Kibeho. There, the Virgin Mary visits Alphonsine, Anathalie, and Marie-Claire (played well by Nneka Okafor, Mandi Masden, and Joaquina Kalukango). She wants to love them in a blood-soaked land. Initially incredulous, the girls’ various keepers (as Sister Evangelique, Starla Benford is especially fine) start to question their own belief as the Virgin Mary shows signs of her power in the girls’ dormitories, and by arranging nature a little differently than is usually seen. When Father Flavia (a wonderful T. Ryder Smith) turns up as a kind of exorcist to case the joint, his faith is challenged, too. There are a lot of influences here, from Arthur Miller’s “The Crucible” to William Friedkin’s “The Exorcist,” and, with the support of Michael Greif, the director, Hall has produced a show that balances the poetic with the grotesque as beautifully as she balances the comedic with the sad. 11.17.14

Time Out New York, Adam Feldman – Faith is contagious at Katori Hall’s thrilling new play, Our Lady of Kibeho. In a remote Rwandan village in 1981, barefoot teenager Alphonsine (Nneka Okafor) claims to have seen the Virgin Mary. Her peers at school, including the domineering Marie-Claire (Joaquina Kalukango), are skeptical—it doesn’t help that Alphonsine is Tutsi, whereas the others are mostly Hutu—as are the kindly Father Tuyishime (Owiso Odera) and the perpetually cross Sister Evangelique (Starla Benford). But a second girl, Anathalie (Mandi Masden), soon shares Alphonsine’s holy vision and then a third girl, and word of their prophecy starts reaching their town. Are they liars or hysterics? Are they witches or possessed? Or could they be telling a truth that no one, including the variously vested interests of the Church, wants to hear?

Like Hall’s Hurt Village, Our Lady of Kibeho is unabashedly wide in scale and traditional in approach (though it veers in surprising directions). In a welcome change from the stingy dramatic economy of many new plays, this one wants to wow you, and it does. There are 15 very fine actors in Michael Greif’s sterling production at the Signature and moments of wonderful stagecraft, including a breathtaking Act I finale. (The second act draws gasps of its own, notably when a world-wearied Vatican investigator, played by the invaluable T. Ryder Smith, interrogates the girls.) At times, Our Lady of Kibeho suggests an inside-out version of The Crucible, and like Arthur Miller’s classic, it resounds beyond its own plot; questions of poverty, sexism and interethnic tension echo throughout the story. Hall’s passionate play renews belief in what theater can do: It awakens you into a trance. THE BOTTOM LINE Hall casts light on what we may not choose to see. 11.18.14

Wall Street Journal, Terry Teachout – Visit From a Missing Person. A story of faith and doubt after the Virgin Mary appears to a trio of Rwandan schoolgirls. Christianity is the great blind spot of American theater. Most Americans believe in the resurrection of Jesus and the existence of heaven and hell—but in most American plays, these beliefs are treated either as proofs of invincible ignorance or as signs of black-hearted villainy. It says everything about the gap between who we are in life and how we look onstage that the best-known shows of the past decade in which religious believers of any sort figured prominently were “The Book of Mormon” and “Doubt.” So it is stop-press news that the most important new play of the year to date, Katori Hall’s “Our Lady of Kibeho,” not only tells the story of a modern miracle but dares to suggest that it might really have happened.

Actually, it’s not quite right to say that “Our Lady of Kibeho” is about a miracle. Rather, its subject is what is known to theologians as an “apparition.” In 1981 and 1982, three Rwandan schoolgirls, all of them devout Catholics, claimed to have seen and heard the Virgin Mary. Their last apparition was a terrible vision of apocalyptic violence that was later interpreted as a prophecy of the genocidal convulsion in which, a decade later, as many as a million Rwandans died at the hands of their fellow countrymen. The Catholic Church subsequently investigated these apparitions and declared them in 2001 to be “authentic.”

This the stuff of high drama, and Ms. Hall has used it thrillingly well, shaping the real-life story of the girls of Kibeho (one of whom was later killed in the Kibeho Massacre of 1995) into a tightly written play that places a chokehold on your attention right from the opening line. It’s tempting to say that you can’t go wrong with material like this, but part of what makes “Our Lady of Kibeho” so impressive is that Ms. Hall circumvents all kinds of possible dramaturgical pitfalls along the way. Yes, the play has a political background, one that she sketches with crisp efficiency—but “Our Lady of Kibeho” never turns into a rant. Instead of lecturing us about tribal sectarianism in Africa, Ms. Hall sticks to her story: What did the girls claim to see, and did they see it?

Ms. Hall and Michael Greif, the director, have opted to show the girls’ visions onstage, leaving it to you to decide whether they were fantasies. No spoilers here: I’ll say only that it’s been a long time since any playwright rang down her first-act curtain with a louder bang. Just as surprising, though, is her willingness to work on a large scale. “Our Lady of Kibeho” calls for a cast of 15, huge by present-day standards, and Mr. Greif’s staging, if not quite monumental, is most definitely grand in its theatrical effects (including a climactic crowd scene that makes cunning use of the audience). Much credit goes to Rachel Hauck, one of our best set designers, for constructing a stage-filling Catholic girls’ school in the Rwandan countryside that looks real without stooping to rigidly literal realism.

Nneka Okafor, Mandi Masden and Joaquina Kalukango play the three visionaries so convincingly that you’ll soon forget that they are, in fact, seasoned actors: They behave just like giggling schoolgirls who’ve been invaded and transformed by the supernatural. Owiso Odera, Starla Benford and Brent Jennings are likewise credible as the school’s head priest and nun and the town bishop, the last of whom is properly skeptical of the girls but no less aware of what it might mean were his impoverished diocese to be recognized as the site of a miracle.

The most interesting performance is, not surprisingly, elicited by the most interesting character. Father Flavia (T. Ryder Smith) is an investigative priest dispatched from Rome by the Holy See to determine whether Alphonsine, Anathalie and Marie-Claire are anything more than hysterical teenagers. Having exposed a few too many phony miracles for his soul’s good, he has become a doubter in spite of himself: “Belief in the impossible trumps even the power of believing in God, which is in itself quite impossible.” Mr. Smith gets him so right that you’ll be thrilled by the soft-spoken subtlety of his impersonation.

As for the play itself, one keeps waiting for Ms. Hall to lapse into the sniggering condescension with which the enlightened skeptic regards benighted believers—but it never happens. To be sure, one or two of her characterizations are obvious, especially that of the head nun, who smacks a bit too much of the cranky Hollywood-style Mother Superior. Nevertheless, the personalities and experiences of all of the characters, like their faith, are presented with complete seriousness.

So…did it happen? You’ll have to make up your own mind about that. But if you’re a gambler, take a flier on Ms. Hall to nail next year’s Pulitzer Prize for drama. I didn’t care for “The Mountaintop,” her last play, but “Our Lady of Kibeho” is the kind of issue-driven, ethnically flavored story that the Pulitzer judges love—and it also happens to be one hell of an exciting show. That’s a miracle all by itself. 11.17.14

Variety, Marion Stasio – Playwright Katori Hall (“The Mountaintop,” “Hurt Village”) came up with an ingenious method for dramatizing a national tragedy in a way that would make it accessible to audiences who might otherwise be overwhelmed by the events. In “Our Lady of Kibeho,” which was based on real events, the scribe anticipates the 1994 genocide that decimated the population of Rwanda by depicting a 1981 religious miracle that seemed to foretell it. But after pulling off this neat trick, she falls into the trap of the overwritten/underwritten play by dwelling much too long on the miraculous curtain-raiser and avoiding the main event.

Legend has it that Rwanda is so lovely, God spends his vacations there. Peter Nigrini conveys that sense of beauty and tranquility by projecting images of a lush green mountain landscape arching over Rachel Hauck’s simple whitewashed set of a Catholic girls’ school. The year is 1981, a time far removed from the civil war that broke out a decade later and the subsequent genocide in which Hutu tribesmen slaughtered upwards of a half-million members of elite Tutsi clans in less than 100 days.

There are some hints of hostility between the Hutu and Tutsi members of the student body. But for the most part, these young girls in their modest uniforms are the very picture of innocence, getting schoolgirl crushes on their handsome pastor, Father Tuyishime (Owiso Odera), and chafing under strict teaching nuns like Sister Evangelique (Starla Benford). That changes abruptly when a student named Alphonsine (Nneka Okafor) begins having visions of the Virgin Mary. Punished by her disbelieving teachers, threatened by her father, tormented by her classmates, the poor girl becomes a pariah — until two more girls become swept up in the miracle. And once all three of them have been vetted by Father Flavia (T. Ryder Smith), a worldly emissary from the Vatican, they become local celebrities and a huge tourist attraction that puts their little town on the map.

But instead of sharing more of the substance of the prophecies and giving up some specifics about what’s in store for the country, Hall stalls at this apparition stage, lingering over the miracles as theatrical events and giving elaborate (and impractical) stage directions on how to stage them. Under the circumstances, helmer Michael Greif gives fair value for his services. He’s been particularly resourceful at going outside the proscenium and into the auditorium to stage the circus-like atmosphere at the visitations.

But Greif has been far too indulgent of both the playwright’s directorial demands and the performers’ overblown acting. An audience should never be too far ahead of the story or of character development. But we are, and it’s a chore to sit through the repetitive scenes of schoolgirl hysteria and adult foolishness. We’re ready for stronger stuff. 11.16.14

TheatreMania.com, Zachary Stewart – Katori Hall’s Catholic spectacular lights up Signature Theatre . Doubting Thomases will have to work extra hard to unpack and explain away the events of Our Lady of Kibeho, a world premiere play by Katori Hall (Hurt Village) at Signature Theatre. The author doesn’t do any of the heavy lifting for you…and that’s a good thing. Hall’s brilliant play, a simultaneously straightforward yet clear-eyed presentation of a recent bit of Catholic mysticism, leaves you grasping for answers and straining for connections days after the final blackout.

The play is based on the true story of three Rwandan girls who, in 1982, claimed to see and speak with the Virgin Mary. These “Marian apparitions” have since received Vatican approval. Many view them as a prescient warning about the 1994 Rwandan genocide that resulted in the murder of nearly 1,000,000 people.

Scenic designer Rachel Hauck uses the full breadth of the stage to lavishly create the Catholic girls school where the apparitions take place, a cluster of little stucco houses with bright blue doors. They unfold like dollhouses as the scenes require.

The story begins in one such house, the office of the school’s head priest, Father Tuyishime (Owiso Odera). He’s having a heated discussion with head nun Sister Evangelique (Starla Benford) about one of the students, Alphonsine (Nneka Okafor). Alphonsine claims to have been visited by the Virgin Mary. Evangelique thinks she’s a blasphemous liar, but Tuyishime is not so sure. They bicker like they’re in a Rwandan production of Doubt until Tuyishime pulls rank with Sister Evangelique (men always trump women in the church) and decides to handle Alphonsine’s punishment himself.

Yet when the apparitions spread to another girl, Anathalie (Mandi Masden), Evangelique takes matters into her own hands and encourages the school bully, Marie-Claire (Joaquina Kalukango) to go after the two Tutsi visionaries. Marie-Claire whips the mostly Hutu students into a frenzy against them. (Ethnic tension between the Hutu and Tutsi tribes, the source of the 1994 genocide, underscores the events of the play.) Amazingly, however, even Marie-Claire succumbs to Mary’s irresistible charm in a first-act finale that is more exciting and frenetic than most musicals on Broadway.

Okafor, Masden, and Kalukango give staggering performances during their trancelike visitations, complete with zombielike prayer, writhing, and speaking in tongues. As the hard-as-nails head nun, Benford champions our disbelief until the author makes her doubt untenable. Even after that, Odera compellingly embodies a far more complicated angst: not wanting to believe, in spite of all the evidence. The prophecy the girls bear is just too terrible to get behind. “Is it so easy to believe visions of violence when they fall from African lips?” Tuyishime incredulously asks Father Flavia (T. Ryder Smith), a visiting emissary from the Vatican.

Flavia has come to investigate the validity of the visions. “I should have been a lawyer,” the professional skeptic muses before embarking on a series of gruesome medical examinations and grueling tests of faith. He’s there to make sure that everything the girls do and say is in compliance with Catholic doctrine, very much like an intellectual property attorney advocating for his brand.

It’s only in relation to this proprietary attitude toward faith that the specter of doubt creeps into the play. Alphonsine rejects two central tenets of Catholic belief: the trinity (one God, three persons) and transubstantiation (the belief that bread and wine actually become the body and blood of Christ during Holy Communion). Flavia wonders why the blessed mother would choose such an ignorant vessel for her message. In light of that, Bishop Gahamanyi (a distressingly pompous and cynical Brent Jennings) pressures Father Tuyishime to coach her on basic Catholicism, reasoning that if her visions are confirmed by the Vatican, Kibeho stands to cash in big from the flood of pilgrims buying Catholic merchandise.

And flood they do. Under the energetic direction of Michael Greif, a cast of thousands (or so it seems) create a biblical tone during the girls’ public appearances, full of violence and confusion. Greif stages these scenes in the aisle dividing the audience, making us feel like we’re in an immersive DeMille epic. “Nobody wants to see the Bishop,” a member of the rabble shouts as the prelate drones on. “I want to hear the visionaries.” As these fervent masses turn away from the conventional church and toward their new prophets, you can almost sense Edward G. Robinson egging them on from behind.

And like DeMille, Greif offers up plenty of fire and brimstone. Ben Stanton (lights) and Matt Tierney (sound) create an epic onstage storm, including wind blowing through our hair. Projection designer Peter Nigrini flashes terrifying visions of death and destruction across the stage as the girls recite their apocalyptic prophecy.

Committed skeptics will dismiss the whole thing as well-informed intuition. (In an environment steeped in tribal animosity, is it really that remarkable to predict the hills will “run red with blood”?) Yet Hall wisely refuses to let her audience leave the theater wearing a grin of smug satisfaction. Just when you think you have it all figured out, you remember a scene or encounter that calls your version of the truth into question. Our Lady of Kibeho is the rare play that leaves the faithful questioning their faith and the doubtful questioning their doubt. 11.16.14

TheEasy.com, Cindy Pierre – Bottom line: A very polished, brilliant and compelling account of a village in Rwanda that is turned upside down when a girl starts receiving visitations from the Virgin Mary.

In 1981, in the midst of an ongoing civil war in Rwanda between two ethnic groups — the Hutus and Tutsis — a young woman named Alphonsine (Nneka Okafor) begins to make claims of seeing the Virgin Mary and receiving messages from her, the bulk of them urging Alphonsine and everyone else to pray for peace. These apparitions serve as catalysts for confusion, upset, derision, and tests of faith among the people of Kibeho that are masterfully depicted in Katori Hall’s beautiful and enchanting Our Lady of Kibeho.

Set predominantly in and within the outskirts of a school, Our Lady of Kibeho begins serenely and melodically with a choir of young women singing the Angelus, a Catholic devotional. Joined together in unity, the gentle ambiance is soon violently interrupted by Sister Evangelique (Starla Benford), a foul-mouthed, ornery woman who is in the throes of an argument with Father Tuyishime (Owiso Odera), the resident priest. They argue over Alphonsine’s allegations, with Sister Evangelique as the staunt opponent.

Alphonsine, played ebulliently and charmingly by Okafor, is adamant that she is telling the truth about what has been happening to her. Against a simple, but tasteful green background designed by Rachel Hauck, it is clear that Kibeho may be beautiful, but that its residents are not accustomed to the grandeur that Alphonsine seems to be suggesting. Why would the Virgin Mary visit Alphonsine, a poor girl lacking shoes or smarts? What creates even further cause for ridicule, jealousy and animosity is that Alphonsine is Tutsi, the group that, according to the Hutus, is dishonest and lowly but still favored.

Though there are a gaggle of girls who don’t believe Alphonsine, chief among them is Marie-Claire (Joaquina Kalukango), a domineering and oppressive bully who acts like she’s in charge of the girls as well as the superiors. Anathalie (Mandi Masden), a mousy and bespectacled friend to both girls, doesn’t know who to believe until the Virgin Mary starts to appear to her. Soon, a mayhem of Salem Witch Trial proportions unfolds, attracting a visit from Father Flavia (T. Ryder Smith), a skeptical investigator from the Vatican.

At a modest $25 per ticket that is well worth the price and then some, Our Lady of Kibeho offers a wonderful theatrical experience that will delight you, astound you, and hopefully encourage you to re-examine what you believe or don’t believe about faith and the supernatural. Concurrently, because the show is based on real-life events, it also offers a possible, fresh portal into the turbulent relations between the Hutus and Tutsis, a subject that has already been explored in an entirely different way by movies like Hotel Rwanda and various documentaries. Whether you believe that the Marian apparitions transpired or not, Our Lady of Kibeho presents an atmosphere in which the conflicts between the tribes could have been thwarted before they escalated into carnage. That alone gives you something to ponder, if not for the past, but for any battles that arise in the future.

Everything in this production is expertly crafted to create visual and psychological appeal. Director Michael Greif utilizes every inch of the Irene Diamond Theatre, staging scenes and scrimmages not only on the stage, but on the walkways between the audience’s seats. He also elicits first-rate performances from the cast. Together with Hauck’s set design, props and set dressing designer Faye Armon-Troncoso reveals calms before storms with wonderful, swiveling set pieces: on one side, the stable edifice of a dormitory, on the other side, the interiors of rooms that either harbor reverence and devotion or chaos and calamity. Everything, from the jaw-dropping aerial and special effects by Paul Rubin and Greg Meeh to Matt Tierney’s magnificent tribal music all work together to create a powerful experience that is not likely to be forgotten soon.

Yet, the genesis where all the great production elements spring forth could not be possible without a well-balanced, thoughtful, and moving script by Katori Hall. Hall not only creates a fabulous microcosm of Rwanda with a strong, blood-pumping pulse, but she gives each and every technician and artist involved with Our Lady of Kibeho an outlet to shine.The manner with which she handles the melding of two giant topics: war and faith, is remarkable. Here, Hall demonstrates her penchant for pensive and passionate writing.

With the feast day of Our Lady of Kibeho coming up on November 28th, Our Lady of Kibeho is timely for this season. Patronizing this show will not only give you a chance to learn more about what is indelible on the hearts of many in Rwanda, but hopefully, the production will leave its own mark on you. 11.16.14

American Theatre Web, Andy Propst – A Gripping Drama as Faith is Tested. Based on actual events from the early 1980s, the play examines what happens after one of the students, Alphonsine (Nneka Okafor), claims to have had visions of the Virgin Mary and to have received instruction from her. The school’s deputy head nun Sister Evangelique (Starla Benford) dismisses the girl’s stories as lies that she has developed to get attention. Hall also laces this woman’s—as well as many of the other students’—reactions with a healthy dose of bigotry. Alphonsine is an orphaned Tutsi, while the sister and many of the students are Hutus.

Alphonsine can take a little solace in the fact that Father Tuyishime (Owiso Odera), the priest who runs the school, wants to believe her and becomes one of her chief defenders. Still, she has to endure ridicule from her classmates, particularly Marie-Claire (Joaquina Kalukango), a haughty mean-spirited soul and a favorite of Sister Evangelique, who enlists the young woman’s help in tormenting Alphonsine.

Eventually, other girls begin to have the same visions as Alphonsine, including Anathalie (Mandi Masden), a sweet bespectacled young woman who is as much an outsider as Alphonsine, and once reports of the visions have reached the neighboring village, pilgrims begin to flock to the school as do church representatives. The diocese’s bishop (Brent Jennings) comes and ultimately sees the financial boon that the girls’ stories might have for the area. Later Father Flavia (T. Ryder Smith), an emissary from the Vatican arrives, to authenticate or discredit the verity of the girls’ tales.

It’s a gripping drama that director Michael Greif has tautly staged and in the Signature Theatre’s largest theater, The Irene Diamond Stage, his work feels concurrently expansive and intimate. These two diverging senses are created by the environmental production that he and the designers have created. Scenic designer Rachel Hauck and project designer Peter Nigrini give audiences a sense of the verdant mountains in which the school is located by placing screens on three sides of the space which show images of the rolling hills on which the institution is located.

Further, Hauck’s design extends the stage into either side of the house so that some of the action takes place just next to the audience, and Greif’s use of the theater’s aisles and a wide central row mean that other parts of the action literally unfolds around theatergoers. Lighting designer Ben Stanton also has a hand in drawing theatergoers into the piece. During several moments when the young women are going into their trances and having visions, lights blaze into theatergoers’ eyes replicating the blinding light that they are seeing. The creative team goes one step further during these sequences by having a faint incense pipe into the theater, replicating the smell of jasmine that is said to accompany the Holy Mother’s appearance.

But all of this excellent stagecraft might be considered mere trickery were it not for Hall’s fine writing, which manages to make the play feel both like a keen documentary and a rippingly good mystery, and the superb performances that Greif has gotten from the company. Most notable are Okafor and Masden who imbue Alphonsine and Anathalie, respectively, with sweetness, fervency, and even a modicum of fear. Their work is beautifully matched by Benford’s turn as the embittered and vengeful Sister Evangelique and Kalukango’s work as the bullying Marie-Claire. Neither performer shies away from making her character dislikable. At the same time, though, as the play progresses, they each find ways to embrace and reveal the humanity that lies underneath the characters’ exteriors.

Similarly, Odera brings warmth, compassion and sadness to his portrayal of the man responsible for guiding the school while Jennings makes the bishop a religious bureaucrat of the highest degree. As the papal representative, Smith’s work has a continental flair, a healthy sense of world-weariness, and, most important, an air of genuine religious commitment to it.

Those familiar with the history that has inspired Our Lady of Kibeho will most likely know what the fate of the young women and their visions were. For those unfamiliar with how the tale ended, it seems unfair to reveal any more. Regardless, it must be said that the play and production are theatergoing of the highest order. 11.16.14

New York Theatre, Jonathan Mandell – It took me nearly to the end of “Our Lady of Kibeho,” a play by Katori Hall based on a true story about three Catholic schoolgirls in 1981 Rwanda who reported having a vision of the Virgin Mary, before I gave up on it. It was the moment when Alphonsine, one of the visionary schoolgirls, calls out to the villagers: “Join us, join us in prayer. Lift your hands to the sky!” and several members of the audience did so.

Shouldn’t there be a separation between church and stage? There is nothing in the U.S. Constitution that requires this, but there may be something in my constitution – and I suspect the constitution of the average New York theatergoer – that calls for more skeptical/analytical distance than we are allowed in “Our Lady of Kibeho.”

This is too bad, because Hall’s choice of subject is, at least theoretically, fascinating.

Kibeho was a small village that was unknown to the outside world until two events occurred – the report of the Virgin Mary sightings that began in 1981, and the Kibeho Massacre in 1994, part of the Rwandan Genocide that year that in just 100 days resulted in as many as a million people slaughtered, or about a fifth of the nation’s entire population. Some people later linked the vision and the massacre – as does Hall’s play: The Virgin Mary was warning of the coming horror.

“Our Lady of Kibeho” begins after Alphonsine (a luminous Mneka Okafor) has already reported seeing the vision of the Virgin Mary, and is about to be punished for lying. Sister Evangelique, the no-nonsense head nun at Kibeho College portrayed by Starla Benford, is sending Alphonsine to Father Tuyishime for a beating, but the priest (Owiso Odera) is too kind-hearted to do so.

Soon, Alphonsine’s classmate Anathalie (Mandi Masden) is also having the visions.

What follows is a series of miracles presented to the audience – Anathalie’s father tries to drag his daughter out of the school, but she suddenly is as heavy as a building; a nasty classmate Marie-Claire (Joaquina Kalukango) burns Alphonsine’s arm with a candle but it does not burn – until Marie-Claire too is entranced by the vision….and all three girls levitate in their dorm.

The Kibeho villagers start calling the girls the Trinity, and Rome sends Father Flavia (T. Ryder Smith) to investigate the veracity of the miracle. When Alphonsine is in the middle of a “rapture,” Father Flavia jabs a huge needle into her sternum, causing her to bleed – a test, we’re told, demanded by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. She is oblivious to the pain, looking heavenward.

There are hints in this play of the more layered work it could have been. The local bishop (Brent Jennings) seems a little less than saintly – he’s married, for one thing, and he is eager for Rome’s confirmation of the miracle because it will boost tourism as it did in Fatima.

But when the young women start flittering their eyes and beaming heavenward, it recalls the scene of mass hysteria among the young women in Arthur Miller’s “The Crucible,” except this time we are supposed to believe it – indeed, we are given no choice.

Hall has said she wanted to write about the Rwanda genocide through a side door, rather than confront it directly, but, while she offers occasional glimpses into the tribal hostility between the Hutu and the Tutsi, the allusions to the holocaust to come feel tacked on and nearly cheap, an excuse for some fancy stagecraft.

The playwright has a history of using stage effects to try to induce a sense of spiritual wonder. In the work for which she is best known, “The Mountaintop,” Hall climaxed the story of Martin Luther King Jr.’s last night alive with a contemplation of the cosmos – the motel room breaks apart, and we are presented with a starry set that is meant to be awe-inspiring, accompanied by a fervent monologue. The effect had the perhaps unintended consequence of seeming to try to turn King into a saint, thus paradoxically undermining the non-sectarian accomplishments of this American hero.

I doubt Hall is using her skills as a playwright and her predilection for stage magic to proselytize for a specific religion. But, despite a hardworking, appealing cast, some moving moments and an inventive design team under the direction of Michael Greif, the experience of “Our Lady of Kibeho” was ultimately akin to attending an overlong service at a church to which I don’t belong. 11.16.14

CurtainUp.com, Elyse Sommer – As projected image shown on three sides of the Irene Diamond Stage illustrate, Rwanda, the setting of Katori Hall’s new play, is indeed beautiful. But look closely at the program’s cast list page and the last word of the text for that setting: “Kibeho, Rwanda, 1981-1981. Before.” As with her previous play at the Pershing Square Signature Center, Hurt Village, as well as The Mountaintop, which premiered in London (see links to review at the end of this review), Hall has once again used actual events to jump start her imagination. This time she’s let that very fertile imagination take her far away to Africa, also the setting for Lynn Nottage’s Pulitzer Prize winning Ruined (interestingly Nottage mentored Hall’s 2007 Hoodoo Love).

That foreboding “Before” connects Hall’s fascinating story of a trio of Kibeho schoolgirls’ claim to having visions of the Virgin Mary to a down-the-road tragedy— when a civil war turned once peacefully coexisting neighbors against each other and the beautiful village of Kibeho became the site of a brutal massacre.

Hall’s drama plays out in the all-girls Catholic school over a period of two years (1981-1982). Alphonsine Mumureke (Nneka Okafor), the daughter of a banana farmer, is the key visionary. It seems that the Virgin Mary has chosen this simple girl to be an urgent messenger to Rwanda’s President so that the bloodshed that was part of her miraculous sighting could be prevented. But like many messengers bearing news people would rather not hear, Alphonsine’s vision is met with hostility and disbelief, both by her classmates and most especially by the school’s head nun, Sister Evangelique (Starla Benford) who is convinced that this is an attention-getting ploy.

Alphonsine’s only source of support and understanding is the school’s principal, the handsome Father Tuyishime (Owiso Odera), on whom all the girls have a crush. The plot deepens and becomes much more than another Song of Bernadette story when two other students — Marie-Claire Mukangango (Joaquina Kalukango) the oldest and initially most firm non-believer, and Mandi Masden (Anathalie Mukamazimpaka)— turn this into a triple miracle. With the arrival of the head bishop (Brent Jennings)and a representative from the Vatican (T. Ryder Smith), the school and the surrounding village become surrogate explorers of questions larger than the validity of the miracles.

The cause and effect of a miraculous vision’ mushrooming into a headline making story literally turns Kibeho into a global village. It also turns Our Lady of Kibeho into a complex drama that explores how individuals, groups and countries deal with moral, economic and political repercussions of such events.

The cause and effect of a miraculous vision’ mushrooming into a headline making story literally turns Kibeho into a global village. It also turns Our Lady of Kibeho into a complex drama that explores how individuals, groups and countries deal with moral, economic and political repercussions of such events.

The excellent performances from the multi-tasking ensemble as well as the actors in the pivotal roles make Ms. Hall’s play as entertaining as it is challenging. You don’t have to believe in miracle sightings to be moved by Nneka Okafor’s ethereal Alphonsine.

As cogently portrayed by Starla Benford even the play’s biggest doubter, the strict and determined Sister Evangelique, isn’t all meanie as evident when she reveals how she came to her commitment to save the girls in her charge from a life of drudgery and too many babies. Actually, it’s because there are neither villains or heroes here, and because the dialogue is often quite funny, that Our Lady of Kibeho is free from being doctrinaire or polemical.

Some of the most compelling scenes involve the three very different priests. T. Ryder Smith is a source of both scary high drama and wry humor as Father Flavia, the representative sent by the Vatican to test the validity of the girls’ visions.

Director Michael Greif has given Ms. Hall’s mesmerizing, multi-faceted play the deluxe production it deserves. He’s not only gotten the right performances from the main players but helped the ensemble to handily navigate multiple roles. His inventive use of all the Irene Diamond Stage’s aisles, including the one between rows G and H, puts the audience right in the center of some of the most vivid group scenes.

As the actors spilling into the orchestra section encloses the audience in the play’s action, so Peter Nigrini’s projections effectively broaden and clarify Rachel Hauck’s lovely, place defining set. Emily Rebholz’s costumes add authenticity. Ben Stanton and Matt Tierney lend haunting visual and aural support. A scene showing the girls levitating and a remarkably realistic storm (courtesy of designers Greg Meeh and Paul Rubin) round out a truly impressive production.

Too bad that even though the Kibeho girls’ miraculous sightings were declared to be real, there was no miraculous acceptance of and preventive acting on the dark future they foretold.11.18.14

Lighting and Sound America, David Barbour – Just about the last thing one expects to see in the theatre these days is a play about Marian visions. Nevertheless, the very brave Katori Hall takes on the true story of three young Rwandan girls who, in 1981, began to see appearances of Mary, the Mother of God. Hall dares to treat the experiences as quite possibly authentic, but this is not a drama of inspiration. At times, it plays like a thriller, and it climaxes in a bloody and frightening preview of Rwanda’s future.

The play unfolds at Kibeho College, a Catholic girls’ secondary school in Rwanda, in 1981 – 82. Or, as the program, says, “Before,” knowing that nothing more is needed to remind us of the horrific tribal violence that will ravage the country. When Father Tuyishime, the priest who runs the school, casually says, “Tutsi women always have the prettiest smiles,” the remark sends a frisson of fear, because we know too well where the divisions of the Tutsi and Hutu will end up. Later, when someone says of the Tutsi, “They think they are better than everyone,” the creeping sense of dread only increases.

The first of the visionaries, Alphonsine, bemuses the school’s superiors and earns the scorn of her fellow students with accounts of her sightings. Father Tuyishime gently tries to talk her out of them, but is gradually taken in by her sincere descriptions, which do not seem to be the product of an overwrought or mischievous mind. (When asked to describe the Blessed Virgin’s appearance, Alphonsine says simply, “She was not white or black. She was just beautiful.”) The other girls at the school are convinced that Alphonsine is a fraud, and when she slips into a vision, they try to distract her by playing an improvised game of ring toss, trying to make their rosaries land on her outstretched arms.

But soon Alphonsine is joined by fellow students Anathalie and Marie-Clare. The latter is one of the school’s tougher nuts–in a rage, she tells Sister Evangelique, who oversees the girls, “I could run this place better than you”–and her submission to the visions sends shock waves through the school. By now, word is starting to get out about the girls, and not everyone is happy about it. The father of one of them furiously asks, “If the village thinks I have a daughter who is a witch, who will buy my bananas?” When, during a vision, two of the girls appear to float in the air, and the bed of a third rises up of its own volition, it becomes impossible to keep the news inside the school walls.

Indeed, the outside world will intrude more and more on Kibeho College. A boy claims to be healed by one of the girls and other locals experience a vision of the sun spinning in the sky. Father Flavia, a skeptical investigator from the Vatican, shows up to conduct invasive, sometimes remarkably cruel tests. (He injects one girl with a sharp needle during a vision; she does not react in pain, but bleeds in the shape of a cross.) The priest cannot credit how such ordinary-seeming young ladies, with their shaky grasp of basic catechism, can be having such extraordinary experiences, but one when one of them speaks to him, in Italian (a language she does not know) of intimate family matters, he is stunned. Meanwhile, the local bishop wants to create an African Lourdes that will bring in dollars from devout tourists.

It all builds to a stunning climax in which the girls, surrounded by crowds of the faithful and covered by television news, deliver a message not of piety or hope but of the bloodbath to come. This sequence is vividly rendered by the projection designer, Peter Nigrini, and the sound designer, Matt Tierney. Throughout Our Lady of Kibeho, the Rwandan characters refer to their beautiful country as the place where God comes for His vacation. Primed to receive a message of piety, they instead learn that they are living on the edge of an abyss.

Hall constructs her strange story with masterful skill, carefully ratcheting up the tension in each successive scene while taking time to flesh out each character and weave the web of friendships, rivalries, and crushes that make up the life of the school. Michael Greif’s direction rightly doesn’t hurry the drama along; he is confident that we will be drawn into the mystery of the girls and he saves his big effects for the climax, when they make such an unnerving impression. The excellent cast includes Nneka Okafor, Mandi Masden, and Joaquina Kalukango as Alphonsine, Anathalie, and Marie-Clare; Starla Benford as the tough, unbelieving Sister Evangelique; Owiso Odera as Father Tuyishime, who struggles with the evidence in front of his eyes; and T. Ryder Smith as the silken, cynical representative of Rome.

Our Lady of Kibeho is a big play and the production team has provided an expansive, evocative design. Rachel Hauck’s scenic design makes use of a series of low-slung buildings; one of them revolves to reveal Father Tuyishime’s office and others can be arranged to make the interior of the girls’ dormitory or the yard outside. These are surrounded by palm trees, and, above the stage on the side walls, a trio of projection screens show Nigrini’s images of the Rwandan countryside, which go a long way toward confirming the characters’ high opinion of their homeland. Ben Stanton’s lighting design creates some powerful effects with sidelight, but at times I wished he had focused more on the actors’ faces; in some scenes, set at night, with unfamiliar actresses dressed in school uniforms and similar wigs, it can be a little difficult to tell who is speaking. Tierney’s sound design ranges from the voices of girls raising their voices to God to a terrible thunderstorm that harrows the stage. Emily Rebholz’s costumes, which consist mostly of clerical garb and uniforms, feel right, and she dresses the smaller roles, including that of a news reporter, in a way that feels authentic to the early ’80s time frame.

Our Lady of Kibeho ends on an unsettled note, with the visions seeming to disappear and Father Flavia heading off to Medjugorje, Yugoslavia, the site of another historically accurate–and more widely disputed–set of Marian appearances. All seems calm once again, except that a terrible storm is coming, one that everyone in the play has been warned about, but which nobody seems able to accept. In the end, the authenticity of the girls’ visions is almost beside the point; what one takes away is the awareness of how easily a civil society can slide into bloody chaos. It’s a thought that should give pause even to the least religious member of the audience. 11.24.14

NY Arts Review, Greg Bauer – Katori Hall’s Our Lady of Kibeho is currently on view as part of the Signature Theatre’s Residency Five series productions. Directed by Michael Greif (Rent) with a top-notch cast, it’s a powerful and potent alchemy of the theatrical arts, combining an effective blend of emotion-filled storytelling, music, set design, lighting and special effects that can only be appreciated on-stage and in real time. Hall takes as her subject the incidence of an apparition of Mary to three students of a village school in Kibeho, Rwanda in 1981 and 1982, and illuminates the process the Roman Catholic Church uses to prove or disprove matters of official apparitions of Mary. Well known incidents of Marian apparition include Our Lady of Fatima and Lourdes, but several other apparitions were verified but are little known, including this particular incidence of revelation in continental Africa.

The lead roles of the first girl to “see” the mother of God, Alphonsine Mumureke, and the priest in charge of her school, Father Tuyishime, are strongly portrayed by the charismatic Nneka Okafor and Owiso Odero. Without their riveting portrayals the production would be less focused and not as powerful. A weak link of the production, however, is the key role of Father Flavian portrayed by T. Ryder Smith. Flavian is a Vatican emissary whose assignment brings him to Africa to assess the claims of an official Marian apparition, but Smith employs a sketchy Italian accent which becomes a distraction in an otherwise unassailable production. The process of evaluating the apparition is complicated by the cynicism of the local second-in-command at the girls’ school, Sister Evangelique, a skillful Starla Benford in a challenging, multiple-layered role, as well as the local Bishop portrayed by Brent Jennings. Benford is effective and heart-breaking as a nun whose faith is brought into question in an obvious echo of John Patrick Shanley’s Doubt: A Parable in a bit of role reversal where the priest and nun are both conflicted with the truth.

Credit must be given to Greif for his seamless production and also to Michael McElroy for his contributions of original music and musical direction. The girls at the school often sing in lilting choral arrangements within the context of the play, though the show is clearly not a ‘musical’ in the traditional sense. The program cites Dawn-Elin Fraser as dialect coach whose work is admirable, though she apparently never had time to assist Smith with his role. Also of note is the fluid set design of Rachel Hauck which allows for smooth transitions as the story progresses.

Signature deserves credit for offering its state-of-the-art facility to produce first-rate productions for its resident playwrights. Hall takes a difficult story and creates a moving portrait of a difficult and complicated spiritual journey. Our Lady of Kibeho‘s large cast effectively transport the audience to Rwanda where the horrors of that country’s internal conflicts are foreshadowed in this harrowing story of fear, faith and fate. 11.18.14

EdgeNY.com, Marcus Scott – Make no mistake; there is a cultural renaissance of poignant material by African-American storytellers happening on screen (Justin Simien’s “Dear White People”) and on stage (Branden Jacobs Jenkins’ “Appropriate” and “An Octoroon;” Robert O’Hara’s “BootyCandy”). Even though there are stellar shows rooted in or deeply influenced by Black culture that have reached ear-splitting critically acclaim (Lanie Robertson’s “Lady Emerson’s Bar & Grill”), warranted mixed reviews that provoked a cult following (the Itamar Moses-penned “The Fortress of Solitude”), or were produced dead-on-arrival (Todd Kreidler’s “Holler If You Hear Me”), shows by Black writers rarely hit on or off The Great White Way.

Black women in particular are still thought of as contrary in theatre. In recent years, a pantheon of women, which includes Suzan-Lori Parks, Lynn Nottage, Kirsten Childs, Lydia R. Diamond, Tracey Scott Wilson, Regina Taylor, Tanya Barfield and Dominique Morisseau, have risen as the forces of nature on the stage, spinning disenchanting narratives about the human condition on both sides of the Atlantic. In just a few short years, Katori Hall has materialized as a beacon of such virtues. Anyone who has seen the 2011 star-studded Broadway production of “The Mountaintop” at the Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre could attest to that.

Returning to Pershing Square Signature Center after her play “Hurt Village” made its world premiere in 2012, Hall returns this year with the phantasmagorical “Our Lady of Kibeho” in performance at the Irene Diamond Stage. Based on a true story of three girls who, between 1981 and 1982, claimed to be able to see and communicate with the Virgin Mary, Hall designs a numinous analysis of the scared and the profane with sensational sangfroid.

The narrative follows 17-year-old orphaned Catholic schoolgirl Alphonsine (played by an incandescent Mneka Okafor), who has previously reported experiencing visions of the Madonna herself, being penanced for lying by the administration. Within the office of Father Tuyishime (Owiso Odera), an intense confab between the handsome head priest and the head nun Sister Evangelique (played with pious fury by Starla Benford) play out, with the two arguing what to do with her.

Sister Evangelique believes Alphonsine to be a blasphemous false prophet, while Father Tuyishime raises more questions, like if the Virgin Mary was “muzungu” (i.e. white) or not. He disciplines the young woman lightly for her “tall tells,” much to the chagrin of his Sister who sends her in for a beating. But then something strange happens: Alphonsine’s classmate Anathalie (played by a prim Mandi Masden), another Tutsi, begins having the visions, too.

Soon after, Sister Evangelique takes matters into her own hands and reassures the devout browbeater Marie-Claire (played by a brilliant Joaquina Kalukango) that she will not be punished if she quashes these young visionaries, first by giving Alphonsine a pinch when she falls into reverie, and then burning her by candlelight, with other Hutu girls as her faithful minions.

However, when Marie-Claire later succumbs to the visions of the Virgin Mary herself, the group began to be worshipped by the village folk who began to dub them “The Trinity.” Considering that Alphonsine, who is not an ace student, discards the idea of The Trinity (The Father, The Son, The Holy Spirit) and transubstantiation (the belief that during Holy Communion, the bread and the wine used in the sacrament become body and blood of Christ), is a part of that trio is kind of ironic.

With Katori Hall’s “Our Lady of Kibeho,” the audience is raptured to a pre-holocaust Rwanda in a woolgathering of Catholic mysticism; where the faithful ask fail to ask the right questions.

But, outrage is fueled and Rome sends Father Flavia (T. Ryder Smith) to investigate the authenticity of the phenomenon happening in Kibeho. He is a skeptic and possible racist who finds it unlikely that Madonna would even speak to the young women “in the jungle.” Get ready to cringe: One of his many tests, authorized by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, includes an awful bit of bloodletting when he punctures a gargantuan needle into Alphonsine’s sternum.

Like Alphonsine, Father Flavia has no clue why she’s been chosen as the vessel for such a message, as she clearly has little understanding of the essential teachings of the bible. But this doesn’t stop the disturbingly smug Bishop Gahamanyi (played cynically by Brent Jennings) from confronting Father Tuyishime to drill the mystic on basic Catholicism, in hopes the village would become a bankrolling tourist attraction for righteous pilgrims across the world. Miracles and unnerving enchantment follow.

Helmed by director Michael Greif, the show’s carnival-esque ambiance snakes along with some lavish stagecraft, breaking the fourth wall of the proscenium and immersing itself in the crowd as the congregation of the village people longs for answers from God or whoever will listen.

Light and sound designers Ben Stanton and Matt Tierney generate perhaps one of the best onstage storms with all of the best gusto present-day theatre makers have to offer, and projection designer Peter Nigrini generates some of the most horrifying panoramas of hell one can muster amid the chanting of apocalyptic divination.

As the scribe of the real life fable, Hall frames an entertaining examination of the pollution of religious hysteria and its ability to cross-pollinate among the born sinners and the faithful, proselytizing less about the powers of faith but the power of human connection. This series of Marian apparitions has since obtained Vatican approval as it is now viewed as prophetic caveats of the 1994 Rwandan genocide (and the 1995 Kibeho Massacre) that ensued the deaths of nigh 1 million elite Tutsi people by Hutu tribesmen, since obtaining Vatican approval.

That’s not really the point of the story really. Quite the reverse: Given history, how could we prevent the inevitable, whether it’s in the fatigued wildernesses of Rwanda or the cannibalized urban jungles of Poland and beyond? The jolting power of Katori Hall’s superb “Our Lady Of Kibeho” will keep the skeptics and children of God alike up at night, pondering the mysteries and eccentricities of faith and the human condition in turns long after they’ve left the theater.

Entertainment Weekly, Thom Geier – Katori Hall’s fact-based new drama, Our Lady of Kibeho, is an unusual blend of the historical and the devotional, with a forthright, unwinking approach to Roman Catholic theology and beliefs. (This world premiere production runs through Dec. 7 at Off Broadway’s Signature Theatre.) Kibeho centers on three Catholic schoolgirls in rural, pre-massacre Rwanda in 1981: a giggly, somewhat slow-witted Tutsi orphan Alphonsine (Nneka Okafor), a bespectacled Hutu girl Anathalie (Mandi Masden), and older class bully Marie-Clare (Joaquina Kalukango, so remarkable as a Memphis teen at the heart of Hall’s Hurt Village a few seasons ago at this very same theater complex).

Like the children at Fatima or Lourdes, this trinity claims to see visions of the Virgin Mary, who has pressing messages both for the church and the Rwandan president. (Their premonitions prove to foreshadow the country’s 1994 genocide, just as the Fatima visions once prophesized World War II.)

At the outset, only Alphonsine claims encounters with the Holy Mother, and she’s soon subjected to taunting from her classmates (including a rival Hutu tribe) and discipline from the school’s head nun, Sister Evangelique (Starla Benford). (”If she thinks that this is the way to get an ‘A’ in catechism…”) But as more girls experience convulsions, with outward signs of otherworldly forces at work (which are cleverly staged by director Michael Greif), even the nun’s skepticism erodes. By the second act, a priest from the Vatican (T. Ryder Smith) descends on Kibeho to examine these homegrown Cassandras—and ultimately confirms their legitimacy.

There are few surprises in this by-the-Good Book narrative, though Hall adds some interesting layers in the dynamics between the rival tribes as well as gender hierarchy in the church; in fact, the prickly relationship between Sister Evangelique and a handsome young priest (Owiso Odera) that Alphonsine finds some solace in recalls a similar one in John Patrick Shanley’s Pulitzer-winning Doubt.

There may, however, be too many layers in the two-and-a-half-hour production. Hall raises some themes in passing (parental pressure, the laxity of priestly celibacy, stolen kisses), only to drop them just as quickly. Still, the playwright has a strikingly earnest approach, and has never been shy about embracing the mystical (an angel plays a key role in her award-winning MLK Jr.-driven breakout, The Mountaintop). She treats her visionaries with clear-eyed matter-of-factness and even nonbelievers may find it hard to reject the testimony of these real-life characters and their expressions of God’s grace. B+

Talkin’ Broadway, Matthew Murray – There’s a saying that God has never had anyone but imperfect people to work with. This notion is central to Katori Hall’s new play Our Lady of Kibeho, which just opened at the Pershing Square Signature Center. In this Signature Theatre Company production, which has been directed by Michael Greif, the imperfection takes the form of three young women at the Catholic Kibeho College in Rwanda, who predict a tragedy that, at least at first, no one believes, and certainly no one can prevent. But the faith that courses through many of the characters is enough to sustain them — and, for that matter, the play — when things do not flow smoothly.

Hall based her story, which is set in 1981 and 1982, on actual events that saw the three women — Alphonsine Mumureke, Anathalie Mukamazimpaka, and Marie-Claire Mukangango — claim visions of, and perhaps possession by, the Virgin Mary, who foresaw terrible things. Hall generally repects the history, and in her telling, Alphonsine (Nneka Okafor), innocent and not deeply educated in doctrine, has her vision first, and talk of what she saw and experienced spreads until both peacemaker Anathalie (Mandi Masden) and troublemaker Marie-Claire (Joaquina Kalukango) are caught in its thrall.

But are they telling the truth? Such is the dilemma facing Father Tuyishime (Owiso Odera), the school’s head priest, and Sister Evangelique (Starla Benford), the head nun. There are plenty of reasons to doubt the women, but faith manages, and it’s not long before the school, and the whole town, are caught up in the fever of the girls’ prophecies. Which means it’s not long before the Vatican hears about it and gets involved, too, sending Father Flavia (T. Ryder Smith) from the “miracles office” to determine whether what’s happening is genuine. And if you’re not familiar with the real-world case, you’ll be kept guessing about the outcome until almost the very end.

Captivating as these questions are, however, they’re actually the least interesting part of what Hall’s written. She’s hamstrung a bit by the facts here, and doesn’t always transcend them to make each scene as nail-biting as it could possibly be. (Father Flavia’s examinations in particular are extensive, but more muted than you might expect given their importance.) Much more effective are the characters’ struggles with their own spirituality: Alphonsine’s fretting that she’s not ready for the notoriety that’s been thrust upon her because, say, she doesn’t thoroughly understand the nature of the Trinity; or especially Father Tuyishime’s own crisis, in which he’s no longer entirely sure what — if anything — about his religion he can accept.

Layered on these concerns are the subtle, artfully drawn investigations of the cultural strife that’s long gripped Rwanda. Though there are few outright conflicts between the Hutus and the Tutsis on campus, the anger and prejudices inform every scene and most every relationship — including, and most vitally, among the girls — and set the stage for the horrific genocide that would come only about a decade later (most notably in 1995 to Kibeho itself). Hall presents this as established, if uncomfortable, but draws so little attention to it unfolding that you’re primed to lose yourself in everything else and forget about the terror that’s stalking the edges of the play.

Unfortunately, complete immersion is difficult. Our Lady of Kibeho is scattered and messy, and holds together in its best moments with the help of its dual underlying messages. But with so much going on, it needs all the focus it can get in its staging, and it doesn’t receive that from director Michael Greif. Greif has placed the action so it fills not only the sprawling Irene Diamond stage, but also stretching out into the audience on the sides and in the aisles. Though set designer Rachel Hauck and lighting designer Ben Stanton try to rein things in, many scenes and plot points become fuzzy as you try to follow just the strict motion of the action. Suffering most are the first act finale, in which Marie-Claire is brought kicking and screaming into the fold, and the climax, when everyone in Kibeho learns too much about where they’re heading. Each should be electrifying, but instead tends to circle in place, as though it’s looking for the ideal place to land and not finding it.

The acting is commendable across the board, but worthy of special mention are Okafor, who brings a weeping gentleness to the most unready of all the girls, and Odera, who’s superb at depicting a man who’s lost within his own beliefs, and probably can’t be cured of his confusion by anything as useless as certitude. These two people must come into their own, and in their performers’ hands, that’s exactly what happens.

The final scene underscores this: Though everything that can be known about what’s transpired is known by that point, everyone is still left guessing — about what it means for them, for the world, and for the quest for God that has, on some level, occupied all of their lives. We know more than they do, but by the end you wish you didn’t; there’s too much heartbreak to come, and not even the most fervent warning from Mary can stop it.

As Father Tuyishime stands, looking out at the bewildering future before him, you’ll see him processing as he never has before the realization that God does indeed work in mysterious ways. Our Lady of Kibeho insists we respect that, but also respect the role we play in crafting the kingdom in which He’d have us live. We’re all imperfect people, Hall reminds us at every turn, but we’re capable of achieving great things — and avoiding great tragedy — when we listen more closely to all the voices that surround us. 11.17.14

Letters from the Mezz blog, “Norma” – In the second act of Our Lady of Kibeho, now playing at the Signature Theatre, one priest admonishes another with the line, “You have a weak stomach for faith I see.” The same could also be said for New York theatre audiences, who prefer religious motifs to be accompanied by biting satire—or a big musical number.

Written by Katori Hall, Our Lady of Kibeho does neither, going the route of a drama based on true events. In 1981, Alphonsine Mumureke (played by Nneka Okafor), a student at an all-girls Catholic school in Kibeho, Rwanda, starts to have visions of the Virgin Mary. At first her visions are thought to be the imaginings of a young girl. Then another classmate, Anathalie Mukamazimpaka (Mandi Masden) begins to have visions too. Both girls face the threat of expulsion from the school, and are mercilessly bullied by Marie-Claire Mukangango (Joaquina Kalukango)… until the Virgin Mary visits her, too. The school’s head priest, Father Tuyishime (Owiso Odera) wants to believe the girls’ visions, while Sister Evangelique (Starla Benford), the head nun, does not. Father Flavia (T. Ryder Smith), a priest sent by the Vatican, investigates the truth behind the girls’ visions. What they all soon discover is that the Virgin Mother’s messages also warn of a dark future for Rwanda.

At first, I wasn’t sure what narrative direction Our Lady of Kibeho was going to take. Was it going to be like Doubt, where the mystery depended on the veracity of the characters? Or was it going to treat the religious material with an excess of derision or reverence? Thankfully enough, none of these scenarios play a part in Our Lady of Kibeho. Yes, Mary’s apparitions are presented as fact rather than fantasy (with breathtaking special and aerial effects, designed by Greg Meeh and Paul Rubin). But the strength of the show lies not in its religious stance, but in the faith of its characters. Yes, Alphonsine is the first to receive visions of Mary, and actress Nneka Okafor embodies the role with grace. Still, she feels the burdens of the visions, and is tempted to try and sin to make the visions stop.

Some of the play’s best scenes involve the character’s responses to the visions. Father Tuyishime wants to believe the girls… but he has not prayed in eight years. Sister Evangelique seems to thwart the girls at every turn… but it’s because she wonders why she cannot see the Virgin Mary, too. And Father Flavia is skeptical if miracles can truly come to a village in Rwanda.

The play’s acceptance of the girls’ visions also allows audiences to focus on another dramatic current running through Our Lady of Kibeho: the ethnic tensions in Rwanda that led to the country’s horrific genocide in 1994. In the same way that Cabaret slowly reveals the future devastation that Nazis will bring to Berlin, Our Lady of Kibeho continually makes references to the Hutu/Tutsi conflict. When Alphonsine is initially mocked for her visions, her Tutsi background is also used against her. Marie Claire, who first bullies Alphonsine, is actually pretending to be Hutu… and will later die for it. (The real life Marie Claire was killed in the genocide; in the play, Marie Claire has a vision of her death.) And when Father Tuyishime and Sister Evangelique disagree over the girls’ well-being, there is the underlying knowledge that Father Tuyishime is head of the school because he is Tutsi… and Sister Evangelique is not.

Our Lady of Kibeho is a definite must-see. Katori Hall’s play about three girls who inspire a nation the brink of destruction is as exhilarating as it is devastating—and that is truly a miracle. 11.18.14

New York Theatre Guide, David Dunlow – The show ended and the lady behind me said to her friend, “Makes you wonder, eh?”

“Our Lady of Kibeho” by Katori Hall, which just opened Off-Broadway at the Signature Theatre, does exactly that. It makes you wonder. Centered on 3 young women in Kibeho, Rwanda, in 1981, this play challenges the audience to think in a way that the New York theatre community has not seen in decades.

When Alphonsine Munureke, a student in an all-girls’ Catholic school in Rwanda, begins seeing visions of the Virgin Mary, the school officials quickly dismiss her as engaging in a hoax. Later, they even accuse her of being in a pact with the devil and being a witch. This is until other girls in the school start to have the same visions, prompting the school to call in Catholic clergy from Rome to see if these girls are telling the truth. This conflict lets the audience explore the questions of religion and belief, and in many ways allows us to believe in these visions as much as the girls in the story do.

Via brilliant writing by Katori Hall, the audience takes the girls’ side, knowing that what we have witnessed is true. “You can’t believe the miracle that is staring you in the face,” says the play to the skeptics. The writing is some of the finest that I’ve ever seen because it really only aims to do one thing: to make the audience believe for two and a half hours.

The direction of this play by Michael Greif (known for RENT, Next to Normal, and the currently running If/Then) is light, potent, brave, and perfect. The entire play is staged on ninety-degree angles, except for the moments when the characters see the Virgin Mary, and where Greif brilliantly stages them on diagonals, creating moments of chaos in the school.