Photos by Joan Marcus

Excerpts from reviews

(full reviews below)

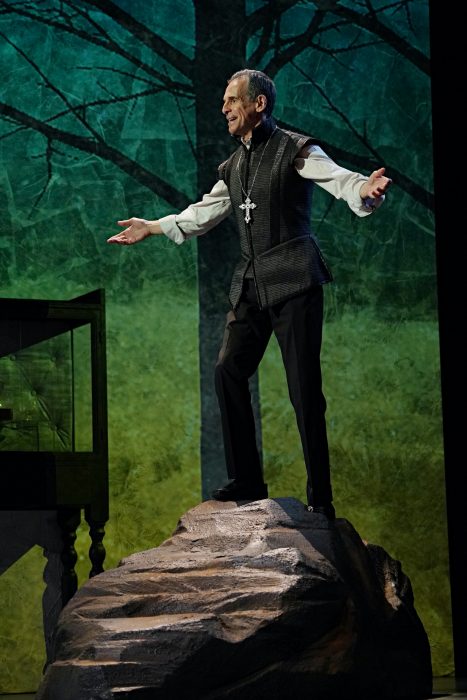

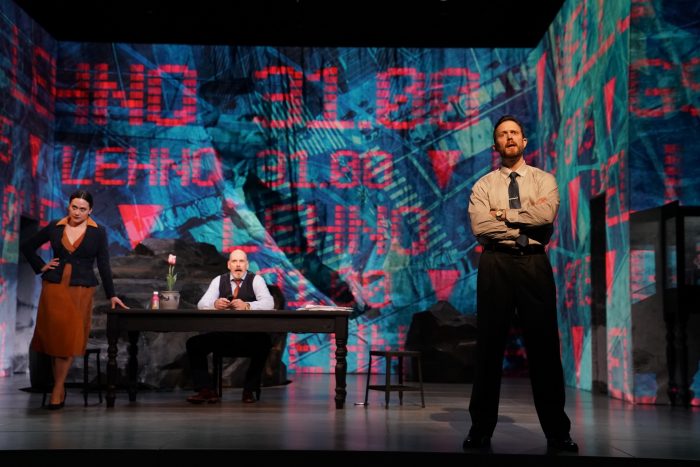

“Fascinating . . . Provocative and fast-paced . . . The play’s nimble overlaps urge us to relive pivotal moments in our nation’s history with at least some consideration of the Lenape’s perspective. . . . Huge boulders grace Mariana Sanchez’s scenic design in which a sturdy table can anchor scenes separated in space and time. A beautiful backdrop of forests is lit or projected upon to create eye-entrancing spaces that suggest the wonders of our land before development, only to become a riot of numbers and digital phrases. . . . It’s good to see T. Ryder Smith back at the Rep after his notable performance in Scenes of Court Life (2016) and here he helps bring needed nuance to a role that invites clichés of prejudice. As Michael, he’s both a church warden and a banker—so that we may see how he leeches away Bobbie’s property as well as her spiritual separatism; in the past, he’s Jonas Michaelius, the first clergyman of the Dutch in North America, who set about “saving” the natives’ children. . . . Christianity and toxic capitalism go hand-in-hand . . . “ – New Haven Review

“Nagle isn’t interested in making simple, surface-levels parallels between the colonization of Manhattan and present-day capitalism. Rather, her collapsing of history shows, rather deftly, how the twin forces of then-nascent capitalism and zealous Christianity grew into the system we live under today — and how Native Americans got the sharp end of both from the very beginning. Just as quickly, the play juxtaposes these extreme beliefs with those of the Lenape, who take a longer, slower, more even-keeled and tempered approach. . . . It’s also worth mentioning that Manahatta is also quite funny. . . . T. Ryder Smith gets to show that his character’s deep faith makes him kind as often as it makes him judgmental. . . . Manahatta’s best move is to let no one off the hook — particularly the largely white audience members in attendance on opening night. We may acknowledge that we now live on land stewarded by the Algonquin peoples, and we may be moved by the story we see in Nagle’s play. But what are we doing about it?’ – New Haven Independent

“Heritage, spirituality and empathy tangle with assimilation, religion and cruelty in Manahatta . . . Set during the housing mortgage crisis in 2008, Nagle puts a new face on that calamity, one long overdue on the American stage. . . . Regardless of the vast distance between Wall Street today and the 17th-century Wall Street, neither the history nor the spirit of the indigenous Lenape Nation can be permanently erased. . . . It’s unfair to single out any one as superlative. Manahatta is a splendid case of directors, actors, designers and run crew bringing their collective expertise to serve the playwright in perfect unison. . . . Lily Gladsone is just right . . . Carla-Rae and Steven Flores are heartbreaking . . . Jeffrey King, Shyla Lefner, and T. Ryder Smith are all outstanding in a range of completely different characters.” – CT Insider

“The play interweaves the 2008 global financial crisis and bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers with the “sale” or Manhattan from the Lenape to the Dutch in 1626. The structure is always there. The degree to which the play is finished may be another story. . . . Nagle writes with wit, aware of the weight of history but also its ridiculousness. Her characters, working across centuries, deliver both weighty lines and zingers that speak directly to how little white people . . . understand about society as a collective, and how much they have shaped it by brute force and manipulation. . . . Cast members are adept at jumping between centuries, bringing to life a history of violence, cultural exclusion, and disenfranchisement by design. . . . Manahatta is still very much a story of what capitalism takes—and takes, and takes—from those who do not conform to its boundaries or to its default whiteness. It is a vital educational text, reminding audiences that the exploitation of Indigenous people was the first step in the creation of an economy based on white supremacy, economic deprivation, free labor, and generational trauma. . . . “ – Arts Council of Greater New Haven

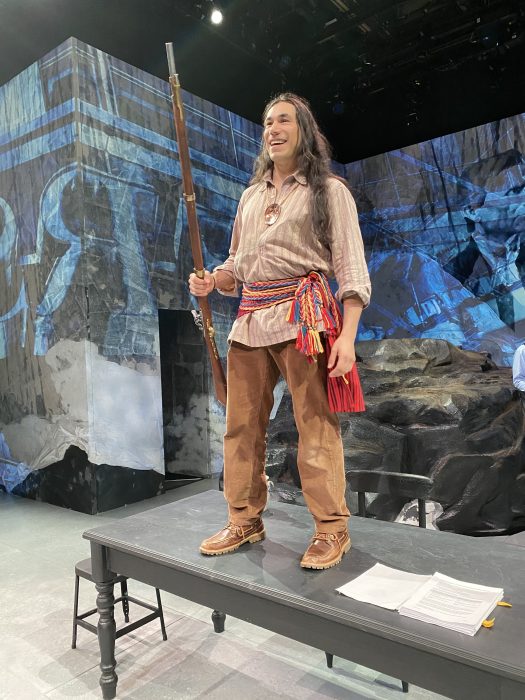

“Extremely engaging . . . The name, Manahatta, actually means “island of many hills” in Lenape and it is an early name of what eventually became Manhattan. . . . the two worlds of Manahatta and Wall Street often overlap, to stunning effect. . . . Mariana Sanchez’s expertly designed set contains elements of both time periods, so one can see a desk in an office on Wall Street placed side-by-side with rocks used by the Lenape people in the 1600s. . . . It also helps that Manahatta contains an excellent group of actors, who all play dual roles, and they work like a finely tuned ensemble. . . . Lily Gladstone is terrific . . . Steve Flores is awesome . . . The sympathetic T. Ryder Smith makes his own impression in the show, notably as Michael, who attempts to work with Bobbie in trying to let her keep her family house in Oklahoma. . . . An illuminating production . . . most highly recommended.” – Zander Opper

“An issue-laden melodrama . . . There are plenty of heavy hero/villain cliches in the story, but Nagle infuses this historical tale of persecution with a strong female energy, including the sort of strong independent woman characters we don’t see often enough in plays. . . . Manahatta‘s sweeping historical scope and its quiet human exchanges are in constant battle. . . . Sensitive drama wins out. . . . The tragic moments are tempered by ones of hope and perseverance. . . . What the play may lose in its overly-theatrical presentation it makes up for with deep understanding.” – Hartford Courant

“Both imaginative and earnest . . . The quality of performance in Manahatta definitely impresses. . . . It is all a great deal to take in. Both the creative team and responding actors pull this relevant and significant production together. Engrossing from the outset, it is something of a challenge, at first, to follow, but that eases as both past and present are cleanly depicted.” – Talkin’ Broadway

Rehearsals

Publicity

Offstage

Full reviews

New Haven Review, Donald Brown – The Recourse of History. Two vexed histories circulate through Mary Kathryn Nagle’s fascinating Manahatta, now playing at Yale Repertory Theatre, directed by Laurie Woolery. In the play’s present, Jane Snake (Lily Gladstone), a descendant of the Lenape tribe that once occupied a major portion of the mid-Atlantic region of what we generally call North America, is working on Wall Street, where she becomes a rising star at Lehman Brothers about the time that it all goes bust—2008. In the past, we see how Jane’s ancestors got euchred out of the island of Manahatta by Dutch traders eager to secure land holdings. The two strains act as background—or analogies—to the other story in the present: Janet’s father, who dies during surgery while Jane is getting hired by Joe (Danforth Comins), leaves to her mother, Bobbie (Carla-Rae), enormous bills and scant means to meet them. The ultimate fate of the family’s home in Oklahoma is the point to be decided; history has already shown us what happened to Manahatta and Lehman Brothers.

And yet. The play’s nimble overlaps urge us to relive these pivotal moments in our nation’s history with at least some consideration of the Lenape’s perspective. Laurie Woolery’s inventive staging of the play does much to help achieve a porous, simultaneous effect. Huge boulders grace Mariana Sanchez’s scenic design in which a sturdy table can anchor scenes separated in space and time. A beautiful backdrop of forests is lit or projected upon to create eye-entrancing spaces that suggest the wonders of our land before development (Emma Deane, lighting; Mark Holthusen, projections), only to become a riot of numbers and digital phrases. An image of Se-ket-tu-may-qua (aka Black Beaver) hovers over the proceedings. In Nagle’s play, this leader of the Lenape in Oklahoma is the descendant of the Native American who rather unwittingly trades away Manahatta when, we suppose, he really thought he was giving hunting permits.

Scenes in the present quickly shift to the past and back again as every actor plays a character in each time period. The most interesting overlap in that regard is Jeffrey King’s dual role as Peter Minuit, who brokers that major real estate steal, and as Dick Fuld, the man at the helm when Lehman went under. In both roles he’s apt to seal a deal with his own very fine brandy, but it’s as Fuld that he adds considerably to the show’s brio, giving the CEO a kind of devil-may-care grasp of how tenuous being on top can be.

Another strong double role goes to Lily Gladstone as both Jane and Le-le-wa’-you. It’s not a sense of tribal ways or historical injustices that drive her as Jane, but rather her grasp of mathematics (there’s a somewhat fatuous sense that she alone adds math capabilities to a group of guys content merely to compute appreciation). Jane is winning, charming and smart, and seems fully on her way to a Working Girl (1988) moment of showing that under-represented populations can succeed in the white man’s world of cut-throat capitalism. As Jane’s ancestor Le-le-wa’-you, she amazes the Dutch by learning English and being able to trade. In both eras, Gladstone’s character is a comer.

At the heart of the play is Carla-Rae’s Bobbie. She about as far removed from the world where her daughter succeeds as can be, in part because Bobbie still considers the land as her ancestors understood it—which means past and present center in her as someone who will never see ownership as a matter of contracts and rights and payments. Her supportive but at times head-shaking daughter Debra (Shyla Lefner) is the character most concerned that Lenape language and customs continue in the 21st century. The play’s strong sense of how the Lenape move and speak and gesture (Ty Defoe, movement director), and of how they conduct themselves—whether in trading furs or accepting or giving wampum—adds human interest to the play’s rich theatrical space, as when Le-le-wa’-you extends her foot into a space where Paul James Prendergast’s sound design creates a running brook. Costumes, by Stephanie Bahniuk, brilliantly transition with ease between times and places and cultures.

Some elements of the production don’t fully jive—such as Steven Flores’ performance as Luke, a male admirer of Jane; the pair went to school together and Flores plays Luke as though he’s still in high school while Jane is poised and professional. Flores fares better in the past as Se-ket-tu-may-qua who seems exemplary of the tribe’s dignity, and his ultimate fate foreshadows theirs.

Other aspects of the play jive in a way that feels more than a bit contrived. It’s good to see T. Ryder Smith back at the Rep after his notable performance in Scenes of Court Life (2016) and here he helps bring needed nuance to a role that invites clichés of prejudice. As Michael, he’s both a church warden and a banker—so that we may see how he leeches away Bobbie’s property as well as her spiritual separatism; in the past, he’s Jonas Michaelius, the first clergyman of the Dutch in North America, who set about “saving” the natives’ children. In both cases, he seems to be present mostly to suggest that Christianity and toxic capitalism go hand-in-hand.

Provocative and fast-paced, Manahatta, which debuted at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival, does better at bringing together the worlds of Manahatta, in the 17th century, and Manhattan, in the 21st than it does at bridging the Manhattan and Oklahoma of 2008. The history in which Se-ket-tu-may-qua and his descendants figure is but sketchily suggested and there’s a sense that the story of Bobbie and Debra exists to provide a homeland backdrop to the reconquest of Manhattan by Jane. And yet, as a New York story, Manahatta isn’t likely to command much urgent attention from twenty-first-century inhabitants of the place. 2.1.20

New Haven Independent, Brian Slattery – Manahatta Sets the Hook. Before the curtain rises on Manahatta there is an announcement in the theater, an acknowledgment that New Haven and Yale are built on Native American land, that other people were here first.

It’s an acknowledgment also heard at Long Wharf, at Arts Council events, and at smaller shows throughout town. Rarely, however, has the event that followed so ably showed the intense need for such an acknowledgment, and at the same time, demonstrated its near-futility compared to the monumental problem it seeks to address.

Manahatta, written by Mary Kathryn Nagle and directed by Laurie Woolery, begins when Jane Snake (Lily Gladstone) secures a job at Lehman Brothers somewhere around the beginning of the 21st century. She’s the one in her Lenape family who “got out”; she grew up in rural Oklahoma, but her gift for math secured her a place at MIT and, from there, a high-powered financial job, where she works alongside cocky Wall Street financiers Joe (Danforth Comins) and Dick Fuld (Jeffrey King). Meanwhile, her mother Bobbie (Carla-Rae), reeling from the loss of her husband and dealing with the enormous medical bills he left behind, decides to mortgage her family’s house to banker and devout Christian Michael (T. Ryder Smith) and his adopted son Luke (Steven Flores), who is also Lenape and has always had a thing for Jane and isn’t afraid to show it whenever Jane visits home. Jane’s sister Debra (Shyla Lefner), also still in Oklahoma, is on a mission to help preserve the Lenape language and thus help maintain her people’s connection to their long past.

Another strand of the plot, interspersed and something intermingled with the more present-day story, follows the purchase of Manahatta — that is, the island of Manhattan — by Dutch East India representative Peter Minuit from the Lenape. Each of the actors play dual roles as Lenape or colonists, and we see first the complex relationship the Lenape develop with the Dutch through trade, and then — after Minuit believes a purchase has been made — the depredations and finally atrocities the colonists force upon the Lenape not long after the deal is made.

The entwining of the present and the past works. Nagle isn’t interested in making simple, surface-levels parallels between the colonization of Manhattan and present-day capitalism. Rather, her collapsing of history shows, rather deftly, how the twin forces of then-nascent capitalism and zealous Christianity grew into the system we live under today — and how Native Americans got the sharp end of both from the very beginning. Just as quickly, the play juxtaposes these extreme beliefs with those of the Lenape, who take a longer, slower, more even-keeled and tempered approach.

For instance, in a scene that feels like watching a glass drop in slow motion, Nagle suggests that the sale of the island of Manhattan was possible due to the Lenape’s very different understanding of human beings’ relationship to the land. In Nagle’s depiction, the Lenape talking to Peter Minuit don’t connect to Minuit’s specific concept of land ownership because they don’t need it. They live on the land and allow others to live there, too, with each person having as much right to it as anyone else, a powerful idea that carries down through the centuries to Bobbie as she mortgages her house to Michael’s bank to pay for her deceased husband’s medical bills. The genocide and destitution of the Lenape (and, of course, all Native Americans) is never far from the frame. But Nagle also takes a sharp eye to the system the colonists created, its zeal to create convert to Christianity and accumulate wealth that has led to a chaotic, predatory system that perhaps benefits hardly anyone — even Wall Street financiers — for very long.

It’s also worth mentioning that Manahatta is also quite funny. The cultural misunderstandings between the colonists and the Lenape are often so (until they become tragic); Jane’s conversations with her co-workers have a savage wit about them; and Bobbie’s general outlook on the problems facing her makes for some very wry asides. Nagle’s play gives each of the characters a good deal of dimension, and each of the actors then fully develops the characters into fully formed human beings. Comins and King give their financiers a surprising compassion, and Comins gets a chance to show his colonist’s mixed feelings for what is unleashed upon the Lenape. Smith gets to show that his character’s deep faith makes him kind as often as it makes him judgmental. Flores plays Luke — and his 17th century counterpart, Se-ket-tu-may-qua, as a man who is much smarter than he initially lets on. Lefner gives Debra a fundamental yet conflicted decency.

In many ways, however, the play belongs to Jane and Bobbie, a daughter striking out into a world geographically, culturally, and monetarily thousands of miles away from where she was born, and a mother assiduously trying to tend for her culture’s roots. Nagle’s play is far too good to make their relationship simply one of conflict. Bobbie is proud of Jane, even as she and Debra both lambast her for not visiting home enough. For her part, Jane is doing her best to be a trailblazer as a Lenape woman working in finance. As the 2007 financial crisis sweeps them all up in its fury, the characters’ actions yield complicated questions with no easy answers. Is Jane breaking into the world of finance or selling out to it? Or both? Or neither? And how would you tell the difference? Is Bobbie’s mortgaging of the house really ignorance of the banking system, or does she have a larger agenda in mind, rooted in her Lenape understanding of the world? As Jane, Gladstone embodies her conflicts and contradictions with nervous ease. But Carla-Rae’s performance of Bobbie is perhaps the most moving. In lesser hands, the character could seem either too silly or too wise; Carla-Rae gets the balance just right, making Bobbie a woman who knows exactly what she wants, and who knows how to accept the consequences.

Manahatta’s best move is to let no one off the hook — particularly the largely white audience members in attendance on opening night. We may acknowledge that we now live on land stewarded by the Mohegan, the Mashantucket Pequot, Eastern Pequot, Schaghticoke, Golden Hill Paugusset, Niantic, Quinnipiac, and other Algonquin peoples, and we may be moved by the story we see in Nagle’s play. But what are we doing about it? we are still caught up in the system started in the colonial era, still prey to its booms and its busts, its unending chase for wealth and its ruinations. Nagle’s play suggests that Native Americans, its first victims, have learned to use the wisdom embedded in their culture to survive it, if barely. Perhaps we could help them do better; perhaps, with humility, we could also learn a thing or two from them how to survive it when the whole thing finally collapses. Oh, do you really think it’ll last forever? 1.31.20

CT Insider, E. Kyle Minor – Heritage, spirituality and empathy tangle with assimilation, religion and cruelty in “Manahatta,” Mary Kathryn Nagle’s play that opened Thursday at Yale Repertory Theatre. Set during the housing mortgage crisis in 2008, Nagle puts a new face on that calamity, one long overdue on the American stage.

“Manahatta,” which continues through Feb. 15 at the Rep, transports theatergoers to that devastating and revelatory time just as “The Big Short” and “Margin Call” time-traveled movie audiences to that tragic episode. What distinguishes these fine films from Nagele’s fine play is that the playwright, an enrolled Lenape citizen, reveals the Native American perspective, zeroing in on a single Lenape family in danger of being erased economically while its culture is all but buried in white-out.

Nagle, who also is a practicing lawyer focused on protecting tribal sovereignty and the inherent right of Indian Nations, aptly personifies this multifaceted cultural conflict in Jane Snake, a Native American recently applying her sharp mathematical acumen to a lucrative career selling questionable mortgages to some of the millions of unwitting homeowners who will soon lose their homes. Her own family in Oklahoma, Jane eventually learns, is among the prey. How she manages these diametrically opposed worlds is the story.

Nagle of course covers the jargon and machinations of that mendacious practice accurately and accessibly. Yet she humanizes and contextualizes how this tragedy affects both her family and herself alike. More interestingly, Nagle weaves in the story of Jane’s Lenape — eradicated from their home, now called Manhattan, by the Dutch as soon as they “purchased” the land in 1626.

As Nagle conceives it, and as Laurie Woolery (director) and Ty Defoe (movement direction) stage “Manahatta,” the intertwined stories from the past and present fluidly fold together like marble cake batter into the pan. Regardless of the vast distance between Wall Street today and the 17th-century Wall Street, neither the history nor the spirit of the indigenous Lenape Nation can be permanently erased.

The biggest take-away from this device is the inherent philosophical difference between the Lenape and the Europeans. Nagle demonstrates this chasm throughout, but most succinctly in the scene where the Dutch purchase the island. Clearly, the Lenape have little concept of owning property and all the materials that go with it. The Lenape’s currency was spiritual, and their economy and culture were collective while the Dutch prized the coin, especially if you’ve collected more than your neighbors.

The rest of the play sees these parallel stories eventually convene, putting a fine point of the many ironies in Jane’s world. Foremost is how religion, namely Christianity, has been used to manipulate nonbelievers, specifically the Lenape. The Dutch of old used Christianity to reap fatter profits in the fur trade, whereas the Lenape’s spirituality is unsullied by the desire to manipulate or mislead.

It’s unfair to single out any one as superlative. “Manahatta” is a splendid case of directors, actors, designers and run crew bringing their collective expertise to serve the playwright in perfect unison. Designers Mariana Sanchez (scenery), Stephanie Bahniuk (costumes), Emma Deane lighting), Paul James Prendergast (music and sound) and Mark Holthusen (projections) all contribute to the cast’s brilliance.

Like everybody else, Lily Gladstone doubles as Jane and Le-le-wa’-you, an ancestor, and is just right. She is at times strong, vulnerable or guileless and, as often is the case, she (like the rest of the actors) distinctly flips from one character to another without benefit of altering costumes or accessories. Like the action, the overall scenography seems effortlessly fluid from one place and time to another, lending the effect that these parallel stories all happen right here and now.

Carla-Rae’s mother character is heart-breaking, as is Steven Flores as Luke, a Lenape who was adopted by a Christian white family, and as Se-ket-tu-may-qua, a proud man who never stood a chance against the Europeans. Jeffrey King, Shyla Lefner, and T. Ryder Smith are all outstanding in a range of completely different characters.

1.31.20

Arts Council of Greater New Haven, Lucy Gellman – The stocks are climbing again, and Jane Snake is to thank for it. So there’s been a dip in the market, she tells investors through her headset. But look at this quarter’s earnings. They’re good. Really good. Red arrows are inching back into the green. In the office, the CEO of Lehman brothers pumps his arms with vulgar excitement.

As she speaks, a member of the Lenape crouches on her desk, then springs to the front of the stage. A shot rings out, and then another. He crumples. Stocks continue to climb. Fourteen hundred miles away, her mother is losing her home. It has been hundreds of years in the making.

Those layered, thick histories define Manahatta, running at the Yale Repertory Theatre through Feb. 16. Written by Mark Kathryn Nagle and directed by Laurie Woolery, the play interweaves the 2008 global financial crisis and bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers with the “sale” of Manahatta from the Lenape to the Dutch in 1626.

The structure is always there. The degree to which the play is finished may be another story.

From its outset, Manahatta’s greatest strength is Nagle’s ability to graft histories onto each other. As the lights come up, the audience meets Jane Snake (Lily Gladstone), a member of the Lenape and eager-eyed MIT grad who has landed an interview at Lehman Brothers. In a glass-walled office in Manhattan—called Manahatta by her ancestors—Jane convinces Joe (Danforth Comins) to bring her on as a securities trader, just narrowly landing the job when she announces she flew out from Oklahoma despite her dad’s open heart surgery.

Back in Oklahoma, her dad dies on the table. Her sister Debra (Shyla Lefner) is struggling to get federal funding for Lenape language classes. Her mom Bobbie (Carla-Rae) is soon knee-deep in debt to a church-touting loan shark, and on the brink of losing the family’s home. It’s the first of many times Nagle nimbly connects the histories of predatory lending, material wealth, and the violence of white supremacy to evangelical Christianity.

To this, Nagle layers the alleged purchase (read: theft) of the land by the Dutch from the Lenape in 1626. It’s a smart collapsing of history, in which cultures with fundamentally different understandings of earth, capital, and domain (Dutch and Lenape; Wall Street banker, hungry investor, and homeowner; patriarchal and matriarchal) are pushed together with devastating consequences.

Nagle writes with wit, aware of the weight of history but also its ridiculousness. Her characters, working across centuries, deliver both weighty lines and zingers that speak directly to how little white people (or people who have come to be known as white) understand about society as a collective, and how much they have shaped it by brute force and manipulation.

Many are based on real people: Lehman Bros CEO Dick Fuld (Jeffrey King) doubles as Dutch West India Company Director Peter Minuit. Comins plays both Joe and Jakob, an early fur trader and Minuit’s second in command. Smith’s Michael is also Jonas Michaeluis, who attempts to bring Christianity to a people who have never needed it.

And at the beating heart of the show, Flores plays both Luke, Michael’s adopted (although whether the adoption is more of a theft, we’re also left to wonder), Indigenous son and an aspiring banker, and Se-ket-tu-may-qua or Black Beaver, the great love of Gladstone’s Le-le-wa’-you.

Cast members are adept at jumping between centuries, bringing to life a history of violence, cultural exclusion, and disenfranchisement by design. King and Comins step back into the 1600s with the pull of a zipper. A shirtless Se-ket-tu-may-qua becomes a jittery Luke with the addition of a rumpled button-down and suit jacket. Jane changes out of the blazer and dress that she has interviewed in—which is also Le-le-wa’-you’s dress—for a suit that can get her to Lehman’s second in command.

In addition to quick changes (costume design by Stephanie Bahniuk), credit here is due to scenic designer Mariana Sanchez and projection designer Mark Holthusen, who have created a stage that marries large, glossy boulders with a Wall Street office and Oklahoma home.

Somehow they all fit, from a projected photograph of the real-life Se-ket-tu-may-qua to a rocking chair from which Debra sings in the Lenape language. Around these three locations, fixed and unfixed in time, the audience takes in kinetic movement (props to movement director Ty Defoe), lines of speech and song in Lenape, and deep nods to Native arming and material culture. They lend themselves particularly well to Fortes, whose Se-ket-tu-may-qua is one defined by tenderness and deep knowledge that transcends speech.

It’s particularly effective in scenes that one sees multiple times, split across some 400 years. As the Lenape are offered guns, horses, and wampum for the island of Manahatta, Nagle sets up a composition that she can repeat over and over, like some horrible film on loop. Watch it once, and the Lenape are being forced from their land. Watch it again, and Bobbie is putting her home up as collateral. Watch it a third time, and the impending bank bailout is about to leave millions of Americans in the lurch.

To it, Woolery has juxtaposed kinetic, lush vignettes with extreme economic (and sometimes physical) violence, in a contrast that succeeds in making one uneasy.

Together, the writer-director team have constructed an enduring sense of right and wrong, replicating phrases (“capital, commerce, ownership” is a big one, the use of addictive substances is another) across scenes to reveal how history repeats itself. Bobbie mentions fry bread, and so broaches the complexity and violence of commodity foods. Michael references a proper deed, and invokes long histories of stolen land, forced migration, and redlining. Debra pushes her mother to speak Lenape, and gets a lesson on the brutal “re-education” programs for Indigenous children that ran well into the twentieth century.

But if it is a much-needed history lesson, Manahatta at times leaves one wanting more depth from its characters and from the script. The play begins with a land acknowledgement that is tailored to the theater, but still leaves out the names of the Indigenous people who stewarded the Connecticut land long before it was Connecticut (that information is included in the program and in the lobby.)

Perhaps it’s meant to be broad, leaving the audience wondering how much of the nation is built on stolen land. But it takes a risk of allowing audience members—particularly white audience members, who are direct beneficiaries of this history of violence – to remain comfortable during and after the performance.

Within the script, Nagle sometimes relies too heavily on archetype for the characters to be real people. That’s not always the case: Debra is both a teaching tool and fully realized person, whose exhaustion and optimism are palpable. King, Smith and Comins are all fairly unctuous and worthy villains, but statements like “he’s definitely gone off the reservation” and “it’s never enough on Wall Street” seem believable when one remembers that a white nationalist with a history of wage theft is the president of the United States.

It’s less true for Bobbie, whose reliance on self-deprecatory humor and overly sentimental asides sell Carla-Rae short. While she is most dynamic when she shows her agency—in a heart-rending scene near the end, she takes being verbally wounded by wounding back—she doesn’t get to do it nearly enough. So too for Flores’ Luke, a canary in a coal mine whose existence remains too much of a plot point.

In a scene that throbs with potential, he tries to navigate the complexities of “passing” in the small-town financial world as Bobbie comforts him on her doorstep. She is about to lose her home, where her family has lived for generations, and stunningly calm in the face of it all. Luke’s hair falls loose around his shoulders; the moment is ripe for revelation. But her speech feels canned, dripping with poetry and sentiment that we’ve heard before. She over-explains to the audience, and loses the moment’s intimacy in the process.

As both Jane and Le-le-wa’-you, Gladstone is keen and resilient, holding her heritage close and at arms’ length at the same time. Her transformation on Wall Street is fascinating to watch: checking the math on subprime mortgages, listening skeptically as she’s told to ignore that math, and ultimately closing deals that she knows aren’t tenable.

Gladstone brings a sharp edge to the role. She pushes back against her superiors (who are also her seventeenth-century oppressors, if one wants to go there) even while she’s code-switching into their slick financial language. She endures their humor and their machismo because that’s what women of color do: endure to survive and, in this case, thrive.

But if she struggles between these worlds, the audience doesn’t get to see much of it. While she comes to barbs with Bobbie and Laura, they are short-lived, and the sense of resolution feels premature. At her most complex, she shows that financial power is intoxicating and real, even for those who have been its victims. But is she selling out, or is she reclaiming what is hers? If it’s the second, at whose expense does it come?

Maybe that’s the point: these characters are an amalgam of the people Nagle has met in the process of writing and workshopping the play (the team has also worked with Lenape Cultural Consultant Joe Baker), and in her fight for Indigenous rights as a partner at Pipestream Law. But it leaves a gnawing feeling that there’s more there, sitting dormant on the stage, ready to come alive.

Manahatta is still very much a story of what capitalism takes—and takes, and takes—from those who do not conform to its boundaries or to its default whiteness. It is a vital educational text, reminding audiences that the exploitation of Indigenous people was the first step in the creation of an economy based on white supremacy, economic deprivation, free labor, and generational trauma. When Peter Minuit mentions that “we have negroes” after the Lenape are forced from the land, when Michael asks for proof of a deed, when Bobbie is forced again to move, it’s all by the same design.

And it’s a telling based on lived experience. In this sense, it is a forceful call to arms to do better, from big national policies to small lessons in the classroom. It is hard to watch the play and not think of the adage, often repeated by the city’s activists, that no one is illegal on stolen land.

Whole centuries are at stake, after all. Isn’t that the point? 2.3.20

ZanderOpper.com – Yale Repertory Theatre is currently presenting the East Coast premiere of Mary Kathryn Nagle’s fascinating play, “Manahatta,” in an extremely engaging production. The name, Manahatta, actually means “island of many hills” in Lenape and it is an early name of what eventually became Manhattan. Interestingly, the play takes place in two different time periods, the world of the 1600s, when the Lenape people had their land violently taken away by Dutch settlers, and Wall Street in the present day, focusing on the character of Jane Snake, a member of a Lenape family who otherwise resides in Oklahoma. As skillfully directed by Laurie Woolery, these two worlds often overlap, to stunning effect.

It also helps that “Manahatta” contains an excellent group of actors, who all play dual roles, and they work like a finely tuned ensemble. What’s more, Mariana Sanchez’s expertly designed set contains elements of both time periods, so one can see a desk in an office on Wall Street placed side-by-side with rocks used by the Lenape people in the 1600s. If this sounds confusing, everything is crystal clear in the production, with especially splendid costume design by Stephanie Bahniuk, which stays as authentic as possible to the original clothing of the Lenape people. It is encouraged that you take a trip to see “Manahatta” at Yale Repertory Theatre to take in the sights and sounds of this artfully constructed play and production.

When the show begins, the focus is on the character of Jane Snake (the terrific Lily Gladstone), who is interviewing for a job on Wall Street at the same time her father is having heart surgery in Oklahoma. Without giving too much away, Jane is part of a Lenape family, who, during the course of the play, must struggle to keep their house in Oklahoma, which eventually becomes over-mortgaged and on the verge of foreclosure. As Jane’s mother, Bobbie, Carla-Rae is quite amazing, with equally good work by Shyla Lefner, as Jane’s sister Debra. And just as these actors play parts in the present day, they also co-exist as characters from the 1600s. The way the performers slip in and out of the two different worlds is smoothly handled and is quite extraordinary.

Indeed, the entire company of actors all work on the same high level. Especially standing out, though, is the awesome Steven Flores, who completely embodies his two parts in the show and is quite a formidable presence onstage. Playing both Wall Street high-rollers, as well as Dutch settlers, Danforth Comins and Jeffrey King are extremely good, and, like their fellow actors, manage to straddle the dual time periods flawlessly. Finally, the sympathetic T. Ryder Smith makes his own impression in the show, notably as Michael, who attempts to work with Bobbie in trying to let her keep her family house in Oklahoma.

“Manahatta” is an ambitious achievement, with magnificent lighting design by Emma Deane and the projection design by Mark Holthusen is similarly striking. Paul James Prendergast also excels as both the sound designer and the composer of the frequently hypnotic music in the show. Director Laurie Woolery keeps the action onstage moving at a good pace, though she also allows for many tender moments in both time periods portrayed in the play.

A word must also be said about Joe Baker, as the Lenape Cultural Consultant, and Louis Colaianni, as the vocal and dialect coach. Everything about “Manahatta” feels period perfect and true to the Lenape people in the show. Such attention to detail makes this show an especially memorable experience and it should be mentioned that there is also a great deal of lively humor in the play, as well. It is stated by one of the characters in the show that that the Lenape people in the present day must stay true to their ancestors and occupy “two worlds” equally. Yale Repertory Theatre’s illuminating production of “Manahatta” manages to accomplish this goal completely and effectively and is, thus, most highly recommended. 2.3.20

Hartford Courant, Christopher Arnott – The actors in “Manahatta” wear many hats. For half of this issue-laden melodrama at Yale Repertory Theatre, the seven performers play either members of the Lenape tribe or the Dutch traders who turn the tribe’s world upside down. For the other half, they are characters in the modern world, either wheeling and dealing on Wall Street or trying to make ends meet in an impoverished tribal area of Oklahoma.

These halves often overlap, with the performers shifting from the 17th century to the 21st with the simplest of costume changes. They drape a blanket over their shoulders, or let their hair down, or swiftly put on a jacket and tie.

The plot is similarly pell-mell, and plays out on a grand scale. The actual moment when the Dutch swindle the Lenape and take control of the land we now know as Manhattan is dramatized. So are the housing market crashes and stock market plummets of recent years. This is high-stakes drama, showing the innocents who are caught in the middle, as well as those who contributed to these seismic economic shifts in both small and grand ways. We meet small-town bankers and Wall Street fat cats, pelt peddlers and tribal leaders.

Some big historical names make appearances in “Manahatta,” among them Peter Minuit, the governor of the Dutch West India Company and Se-ket-tu-may-qua (aka Black Beaver), a legendary Native American leader who spoke several languages and was known for his negotiating skills. Jeffrey King plays Minuit as an insensitive faux-monarch, laying down edicts that cripple those who live on the land he sees as only a sweet commercial deal. Steven Flores’ Se-ket-tu-may-qua is more nuanced, not as transparent in his thinking and behavior, much more soulful.

There are plenty of heavy hero/villain cliches in the story, but Nagle infuses this historical tale of persecution with a strong female energy, including the sort of strong independent woman characters we don’t see often enough in plays. Lily Gladstone plays Jane, a skilled financial mathematician who rises to become CFO of a major Wall Street firm. Carla-Rae plays her mother Bobbie, an Oklahoman homeowner and recent widow whose life is still shaped by her Native American spiritual values. The effervescent Shyla Lefner, who brings a comic brightness to many of her scenes, plays Carla-Rae’s other daughter Bobbie, who is committed to keeping tribal languages and customs alive in her own way.

The women also play rooted, centered, articulate and emotive members of the Lepane tribe. These fictional characters share the stage with the famous names, bringing stories of the unsung and unheard to the forefront of a historical adventure of world-changing proportions.

The scene where Minuit “buys” what we now know as the island of Manhattan from the natives for wampum is painful to watch. We hear those who know the land only as “home” struggling and failing to understand this new concept of ownership, losing the land that they are offering to share.

That scene is mirrored by the modern experience of mortgage and foreclosure, in the era of duplicitous and predatory lending practices.

The elements that bring about some of the play’s best moments also can deliver some of its clunkiest. The actors change in a flash from Wall Street traders to raccoon-pelt skinners, or from warriors to bankers. The set (by Mariana Sanchez) juxtaposes giant boulders with boardroom desks. When a calamity strikes, it does so with over-the-top lighting effects and overwhelming projected images. “Manahatta”’s sweeping historical scope and its quiet human exchanges are in constant battle. Director Laura Woolery (whose other Yale Rep credits include the Latinx drama “El Huracán” and the Shakespearean shake-up “Imogen Says Nothing”) has her hands full keeping the stories distinct and clear when needed, then blending them into a culminating cultural clamor towards “Manahatta”’s conclusion. Woolery has just the right people skills to bring out the heart of this large and unwieldy play, and the iron will of an orchestra conductor in not letting the piece race out of control.

Sensitive drama wins out. Nagle makes the Native American characters self-aware, not naive. She has them laughing at the Dutch traders’ presumptions that men are always the decision-makers, or that the invaders’ aggression will not be met with retaliation.

“Manahatta” is in a worthy tradition of plays that somberly depict the exploitation of native people. There’s Peter Shaffer’s “Royal Hunt of the Sun,” about Pizarro capturing the leader of the Incas, and Brian Friel’s “Translations,” about British imperialism in Ireland, and Arthur Kopit’s “Indians,” which takes some of the same general themes of subjugation and commerce as “Manahatta” into the 19th century. All these plays have scenes in which basic communication problems and differences in fundamental beliefs are played out in fraught stilted conversations, with the invaders willfully misconstruing their intentions or outright lying.

“Manahatta” builds empathy and compassion for its victims of land-grabs and house-grabs, but also shows how, due to their core cultural values, they process these losses differently than others might. The concept of ownership comes up a lot. Spiritual peace is maintained under the most trying circumstances. The tragic moments are tempered by ones of hope and perseverance.

The Yale Repertory Theatre surrounds “Manahatta” with real-world expressions of support for Native Americans. This message is posted in the upstairs and downstairs lobbies, and in the program: “Yale University acknowledges that indigenous peoples and nations, including Mohegan, Mashantucket Pequot, Easter Pequot, Schaghticoke, Golden Hill Paugussett, Niantic and Quinnipiac and other Algonquian speaking peoples, have stewarded through generations the lands and waterways of what is now the state of Connecticut. We honor and respect the enduring and continuing relationship that exists between these peoples and nations and this land.” Such announcements are not unheard of (especially in Canada, where some theaters regularly acknowledge that the land the theaters are on once belonged to indigenous nations), but are still rare and welcome and thought-provoking.

Mary Kathryn Nagle, whose other plays include “Sovereignty” and “Crossing Mnisose,” is a citizen of the Cherokee Nation and was the first Executive Director of the Yale Indigenous Performing Arts Program. She’s also partner in a law firm concentrating on Native American issues.

“Manahatta” hits close to home and has direct knowledge of some of the difficult situations it depicts. What it may lose in its overly theatrical presentation it makes up for with deep understanding. 2.4.20

Talkin’ Broadway, Fred Soko – The East Coast premiere of Manahatta, running through February 15th at Yale Repertory Theatre, succeeds. It is both imaginative and earnest: a fine combination. The revelatory material, addressed through Mary Kathryn Nagle’s insightful script, shifts between the 17th and 20th centuries through the Lenape tribe. This is an intriguing story of Native American people.

It is 2007 and Jane Snake (Lily Gladstone) snares a Wall Street job offered her by Joe (Danforth Comins). From Oklahoma, Jane, whose father recently passed away, abandons her mother Bobbie (Carla-Rae). We learn that the native tribe, a few centuries before, lost its base in Manahatta to traders from Amsterdam led by Peter Minuit (Jeffrey King).

Through its one hour and forty-five minutes, Manahatta demonstrates the odds Native people have faced. Jane works at Lehman Brothers and disaster is imminent. The lure of quick riches is undeniable.

All actors are playing multiple roles in this show, with each contemporary character also playing a character in the past. For example, Jane is also Le-le-wa’-you. In that capacity, she startles the Dutch during the 1600s, with her computational skills and ability to grasp English. Costumer Stephanie Bahniuk places a shawl-like cape over actress Gladstone’s shoulders, with her contemporary dress (the presentation moves backward and forward in time so swiftly) is beneath.

The combination of Mariana Sanchez’s lovely set, Mark Holthusen’s projections, and Emma Deane’s lighting enables instantaneous movement from one era to the other. The Lenape’s Se-ket-tu-may-qua appears, through imagery, behind the actors as they perform. The audience can observe people who lost a foothold in North America several centuries back. The current family, left with unpaid bills and a mortgage payment threat, must grapple to survive in Oklahoma. Jane’s ancestry is of a revered and precious culture, and she is hoping for something better for herself within the male dominated, corporate world of lower Manhattan. That, she discovers, is cutthroat commercialism.

Playwright Nagle has stated that the word Manhattan is a derivative of Lenape’s “island of many hills.” She is a member of the Cherokee Nation, writing with authenticity. Realizing that Lenape people today are not in one geographic locale, she has centered on Oklahoma.

The play is also about strong women. Jane leaves not only her mother Bobbie (Carla-Rae) behind but also sister Debra (Shyla Lefner). All three women are soulful and each inspires. Jane’s trajectory brings her to New York while her older sibling remains at home to support Bobbie.

The quality of performance in Manahatta definitely impresses. It is essential for actors to gracefully flip from one persona to another. Jeffrey King, cast as both Minuit and as Lehman’s Dick Fuld, excels. The men of the production include T. Ryder Smith (Michael and Jonas Michaelius), Danforth Comins (Joe and Jakob), and Steven Flores (Luke and Se-ket-tu-may-qua). All are commendably versatile. The women, however, are profoundly indelible. Their situations are multi-faceted and each finds obstacles which might jeopardize survival. Ultimately, it is impossible not to sympathize with these female characters.

Director Laurie Woolery must accommodate as the show, sometimes through composer Paul James Prendergast’s interesting music, snaps from one century to the other. Ty Defoe, movement director, has an important influence as the actors adapt.

It is all a great deal to take in. Both the creative team and responding actors pull this relevant and significant production together. Engrossing from the outset, it is something of a challenge, at first, to follow, but that eases as both past and present are cleanly depicted. 2.7.20

Journal Inquirer, Tim Leininger – Yale Repertory Theatre is presenting a new drama about heritage, family legacy, and the continued consequences of greed in Mary Kathryn Nagle’s new drama, “Manahatta,” making its East Coast premiere, running through Feb. 15.

Covering parallel timelines, “Manahatta” follows Jane (Lily Gladstone), a member of the Lenni Lenape tribe who is moving from her rural home in Oklahoma to pursue a successful career on Wall Street at Lehman Brothers.

The irony of her motivation is that she is returning precisely to where her ancestors lived and were coerced into selling the island of Manahatta — now called Manhattan — to the Dutch settlers.The story jumps back and forth between Jane and her work at the firm just before the housing market collapse in 2008; her mother, Bobbie (Carla-Rae), who has just put an adjustable rate mortgage on her house to pay for medical bills for her late husband; and Jane’s ancestors of the Lenni Lenape tribe and their dealings with the Dutch.

A Cherokee herself and the first-ever Native American playwright to have a play produced at Yale Rep, Nagle’s use of parallel narrative never strays too far from any of the storylines so as not to have the audience lose interest in what is happening with the various characters.

The story gives a fantastic comparison of the greed, corruption, and manipulative nature of the Dutch settlers with 21st-century bankers and investors. It captures the reality of greed and how the lust for control, power, and money has been around for as long as humankind.

The one complaint I would have with the narrative is casting the same actors for the 2008 characters as the 17th-century characters. I get the idea that it is intended to give a deeper relatability to the characters by having Gladstone play not only Jane, but Le-le-wa’-you as well, the same with all the other cast members, each playing a role from both time periods. But I think the effect of the narrative would be served better if we got to see both Jane and Le-le-wa’-you on stage together at times confronting their respective conflicts. It might create a more cohesive commonality between the two characters.

Another issue with the actors playing roles from both time periods is the costuming. Though I commend Stephanie Bahniuk for coming up with inventive ways to make the costumes as translatable as possible from one time period to the next, sometimes it looks a little awkward. Especially with the Wall Street businessmen who don’t leave the stage and quickly alter their executive looking suits enough to get them to look more Dutch colonial.

Artistically, it gives them a mutual identity, noting that they aren’t all that different from each other even though it’s been 400 years. But I think the transitions would have been a little smoother having different actors playing the infamous Peter Minuit (Jeffrey King) and clergyman Jonas Michaelius (T. Ryder Smith).

This isn’t to diminish the performances by King, Smith, Gladstone, or anyone else. The cast is good. Gladstone is particularly great as Jane, balancing her naivete, arrogance, and heart to keep her likeable as she lets her own success pull her away from her family’s problems.

Steven Flores has a particularly nice contrast in characters as the meek Luke who loves Jane and objects to Bobbie taking on the ARM mortgage, and Se-ket-tu-may-qua, a Lenni Lappe who seeks to avenge his family being duped by the Dutch.

Mariana Sanchez’ scenic design along with Mark Holthusen’s projection design give a unifying atmosphere between the two centuries, intertwining rural 17th-century Manahatta with 21st-century Oklahoma and executive offices on Wall Street.

“Manahatta” does have its stylistic issues, one that could easily be fixed with doubling the casting, but otherwise, it is a compelling human drama that reminds us that our past compels our future. 2.7.20

Identidad Latina, Bessy Rayna – Como crítica teatral, ocupo mi asiento en las salas de teatro a esperar que una obra empiece. Esos momentos de espera siempre están llenos de expectativa. ¿Me va a gustar la obra?, ¿Tendrá algo nuevo que presentarle al público?, ¿Cuál es la calidad de actores?, ¿Del equipo técnico? Siempre que espero ese momento en el que las luces de la sala se apagan y se encienden las del escenario, es como esperar a ver a una amistad que no hemos visto por años, o conocer a alguien por primera vez. El teatro es así. Un género tan especial que nos hace entrar de lleno en las vidas que son representadas en el escenario; o en las historias antiguas, o contemporáneas, que van desarrollándose frente a nosotros.

La obra Manahatta, que acaba de estrenarse en Yale Rep. nos lleva a tres épocas en la vida de dos grupos: indios descendientes de la tribu “Lanape” que ahora viven en Oklahoma, lugar donde fueron llevados sus antepasados al perder sus tierras. La historia de la compañía Dutch Trading Company, y los colonos que “compraron” la tierra de la tribu que vivía en esa área, que ellos llamaban: “Manahatta”. Una vez logrado asesinar o deshacerse de la tribu, establecieron lo que llamaron “Nuevo Ámsterdam” en honor de su ciudad natal, en el 1620. La otra parte de la obra teatral tiene que ver con la joven Jane Snake, quien es graduada de la prestigiosa MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) y consigue trabajo en una firma de comerciantes de acciones. Ella es la primera “indígena” que logra un puesto en este tipo de negocio tan lucrativo.

Mientras Jane se alegra de conseguir el trabajo, su padre está moribundo en un Hospital en Oklahoma. La madre decide que operen al padre para tratar de salvarlo cuando en realidad ella no tiene dinero para pagar el Hospital, una información que ella no le dice a sus hijas Jane o Debra. Es este acto de la madre el que llevará a la ruina a la familia y hasta perder el hogar donde varias generaciones han vivido.

Jane triunfa en su trabajo y tiene una vida de abundancia económica hasta que la crisis de la bolsa de valores, hace que su compañía se declare en bancarrota.

La dramaturga Mary Kathryn Nagle, pertenece a la nación “Cherokee” y es abogada de en casos de protección de los derechos indígenas. Fueron algunos de los casos sobre pérdida de hogares debido a las compañías aprovechándose de personas que no podían pagar sus hipotecas y quitándoles sus casas, que Nagle fue creando los personajes de esta obra.

Podemos decir que hasta cierto punto, Nagle ha tratado de combinar demasiados elementos, lo cual ha producido una obra que no nos llena de satisfacción. Por ejemplo, mientras la madre está perdiendo su casa en Oklahoma, en Wall Street, en Nueva York, en el centro económico de USA se están perdiendo billones de dólares al caerse la bolsa de valores. Mientras los colonos Holandeses le roban la tierra a la tribu que habita la isla, los bancos están haciendo lo mismo con los dueños de casas, a los que les prometieron hipotecas sabiendo los bancos que ellos no tenían suficiente dinero para pagarlos. Al igual que el personaje de “la madre”, miles de personas en EEUU no tienen seguro médico, y tienen que escoger pagar una hipoteca o pagar miles de dólares por cualquier emergencia médica.

Otro aspecto que Nagle pone a relucir, es la participación de la iglesia de la época colonial, la cual trata por todos los medios de “cristianizar” a los indígenas, no solo en el siglo XVII sino también en el XX cuando, según la madre, se llevaron a los niños de la tribu, los metieron en un orfanato y les prohibieron hablar el lenguaje “Lanape”.

A manera didáctica, algo que si logra esta obra, es darnos a conocer de dónde proviene el nombre “Wall Street” y es que en realidad fue una pared de madera de 10 pies de altura, construida por los Holandeses para que los indígenas no entraran a “su ciudad”. También nos enteramos que el nombre original de la isla que ahora llamamos “Manhattan” era Manahatta.

Tres de los actores forman parte de diversas naciones indígenas en el país. Carla-Rae, en el doble papel de la madre y Bobbie, es Seneca/Mohawk/French Canadian; Steven Flores, quien tiene el papel de Se-ket-tu-may-qua en Manahatta y de Luke en Oklahoma es descendiente de Numunuu (Comanche) y Lily Gladstone, en el doble papel de Jane y de Le-le-wa-you, es descendiente de Ampskapi Pikani, Kainaiwa y Nimii’puu nations. El elenco está compuesto por Jeffrey King en los papeles de Dick Fuld y Peter Minuit, el dueño de la compañía de acciones y en colono director de la compañía holandesa. Shyla Lefner también en doble papel de Debra en la sección contemporánea de la historia y de Toosh-ki-pa-kwis-i, la mujer Lanape que tiene que huir para salvar su vida. T. Ryder Smith, actor que hemos visto en Yale Rep en otra obra, tiene el papel del “Pastor de la iglesia”, es quien le da una hipoteca a Bobbie sabiendo que ella no podrá pagarla, y es también el Reverendo Holandés tratando de convertir a los indios. El actor Danforth Comins en el papel de Joe, en su oficina de Wall St. y jefe de Jane, y como Jakob el Holandés, es el único de los personajes masculinos que en algún momento sienten culpa por lo que le están haciendo a los compraron acciones y en su papel de colono, en el pasado de cómo masacraron a los indígenas de la isla.

La obra fue estrenada en el 2018 en el Festival de Shakespeare de Oregon donde, al igual que en esta producción fue dirigida por Laurie Woolery, quien se lució en la dirección de la obra “El Huracán”. Si bien ella trata de mover a los actores de la época actual al pasado, ayudada por magníficas proyecciones en la parte de atrás del escenario diseñadas por Mark Holthusen, esta es una obra que no le permite a la directora entrar de lleno en los personajes, ya que estos han sido creados en una forma sin mucha profundidad.

Me llamó la atención el vestuario de Jane, diseñado por Stephanie Bahniuk, el cual es color marrón claro con un triángulo en la esquina de la falda que no le daba nada de elegancia y el que solo sirvió para distraerme. También la ropa del personaje de Debra, unos pantalones anchos que no eran ni “capri” ni largos, me parecieron que no le agregaban nada a un personaje que en realidad la dramaturga no le dio mucho valor. Al menos no fallaron con la ropa de los hombres, ya sean colonos o banqueros.

Hay que reconocer que es algo estupendo tener nuevos valores en el teatro, nuevas voces de grupos minoritarios de los cuales casi nunca son representados. En este sentido, la obra Manahatta, llena un gran vacío al darnos personajes indígenas con vidas reales y no como los estereotipos que vemos en las películas de Hollywood. 2.3.20