Above: from the Pittsburgh performances

Below: from the Duke performances

Photos by The Hinge Collective

Excerpts from the reviews

Full reviews are below

“This interactive theater work wants to make us ask some provocative questions about war, and it largely succeeds. . . . as oblique in its storytelling as it was confrontational in its methods . . . it does pose an interesing theory about warfare — one that, perhaps unexpectedly, has to do with warfare’s relationship to acting. . . . The venue is a large, bare, long-unused room where the audience of 40 or so began the evening sitting on cinderblocks. A bank of television monitors sat upstage, showing an array of sequences from nature films, surgery films, Hollywood war movies and sometimes infomercials. . . . The three-member cast is headed by Smith, a lean and sardonic fellow who led with a lengthy, amusing monologue. . . . The evening’s keynote motif was an extended riff on The Iliad, our oldest literary epic about war. Along the way — and as Smith shifted in and out of various personas — audience members were conscripted to be Greek gods, fellow soldiers or even just people asked to memorize a single word. Much of the second half, moreover, took place in a menacing near-dark, with flashlights and other small onstage lights the lone illumination. . . . the work’s female characters — a motif of veiling suggests Iraq, Afghanistan — told of oppression that one might wish to go to war to oppose. Yet the play also explored the links between misogyny and violence . . . Much of the audience interaction, for instance, was built around brief interactions in which Smith affixes blame or demands loyalty to his cause, forcing audience members into false choices, and demanding that people make snap, life-or-death decisions in the madness of a moment, sometimes, while literally in the dark. . . . Measure Back is bound to provoke discussions about its meaning and intent. What it suggested to me is that, as if we were all unconsciously actors, we humans tend to play the roles expected of us. . . . ” Bill O’Driscoll, Pittsburgh City Paper

“A reworking of The Iliad with its confrontational approach that insisted the audience pay attention to the details and moral issues of war, whether it were the Greeks vs. the Trojans or the daily conflicts of the 21st century. . . . The night began quietly with a monologue by actor T. Ryder Smith, who partnered with Christopher McElroen to assemble a multimedia play using the poetry of Homer to illustrate that little has changed since the Greeks set sail to retrieve Helen. . . . Opening with jokes and personal patter, Mr. Smith abruptly challenges the audience with a hail of provocative questions, now and then bringing a few members up to cast them in various roles or give them little tasks. Yet, as we moved from our blocks to folding chairs and Mr. Smith from a suit to soldier’s fatigues, Measure Back lost some of its in-your-face bite as it changed into a more traditional play. Dionne Audain and Felicia Cooper joined Mr. Smith in a series of scenes focusing on how women are brutalized in war . . . Measure Back seems still a work in progress as themes are uncompleted or explained in heavy-handed ways. The actors, however, are powerful, threatening and sympathetic despite a complicated script and frequent audio and visual distractions. Be prepared, then, for a physical and emotional workout. ” Bob Hoover, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

“Perhaps it is my age that made me feel that Measure Back is a shallow thing. It’s about war–its history and its present; its whats, hows and whys, and what provokes us to it. This is hardly a new topic, but it is always laudable when artists and thinkers confront it anew. . . . Smith uses The Iliad as source material–although he often seems dismissive of it–but he stays determinedly in the bloody shallows as he attempts to link that ancient tale to modern lives. . . . there are never any painful consequences to the little set-ups, which give way at ADHD speed to something else, or else drag on murkily far past the point one cares to try to understand them. There’s no character we can latch onto, no story through-line, except in a rather esoteric sense. There is plenty of discomfort . . . ” Kate Dobbs Ariail, The Five Points Star blog

“Ignominious . . . a half-baked, meandering, narcissistic exercise by Mr. Smith that not only did not answer any questions, but failed even to ask them in any meaningful or cohesive manner. . . . ugly and mean-spirited . . . I was totally consumed with boredom and stuck in a room with a meandering morass of smugness . . . ” Jeffrey Rossman, CVNC.org

“Measure Back . . . [with] a flippant, gritty tone . . . challenges the audience to directly confront wartime emotions, not as an aestheticized past event but by structuring fictionalized experiences in order to provoke anger, pathos, and contempt. In this way [it] searches for the origins of war (to “measure back”) within the audience members themselves. Audience members stand, speak, vote, and resist . . . making passive spectatorship impossible . . . What was most impressive was the demand placed on me that I make some public choice. These choices came to “define” me in the eyes of the other audience members, and theirs defined them . . . The performance individualized all interactions: “What would have to happen for you and me to be at war?” A network of relationships between individuals replaced the sense of the audience as a multiple mass and the performer as a producer of an affective commodity. . . . The performativity of citizenship, or at least the creation of socio‐political identity within a group, was a highlight of a challenging performance. It provided some measure of hope for individual agency, if not the efficacy of the agency to stop war. At minimum it temporarily dislodged the consumption model of performance and opened up new agentic positions in relationship to an otherwise closed story of war, revenge, and violence. . . . By imagining a new world, and practicing action within it, do we start to create that world outside the performance?” David Bisaha, Etudes Journal

Rehearsal

Above: Dionne Audian, Meera Khumbani, T. Ryder Smith

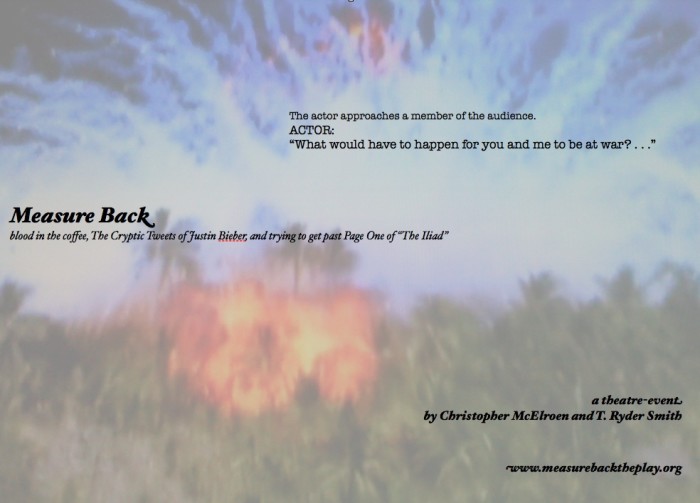

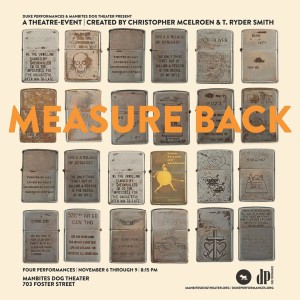

Publicity

Above: Christopher McElroen (r) and T. Ryder Smith (c) interviewed by Frank Stasio (l) on “The State of Things”, WUNC/NPR radio, Durham, NC.

Offstage

Above: the space in Pittsburgh, Monday night; the space, Tuesday afternoon.

Full reviews

Pittsburgh City Paper, Bill O’Driscoll – This interactive theater work wants to make us ask some provocative questions about war, and it largely succeeds.

The work, which put the audience in the role of combatants or potential combatants, was as oblique in its storytelling as it was confrontational in its methods. But it does pose an interesing theory about warfare — one that, perhaps unexpectedly, has to do with warfare’s relationship to acting.

Measure Back, co-directed by T. Ryder Smith and acclaimed Brooklyn-based theater-maker Christopher McElroen, is a world premiere at the Pittsburgh International Festival of Firsts. It’s staged on the top floor of Downtown’s Baum Building (above Space gallery). The venue is a large, bare, long-unused room where the audience of 40 or so began the evening sitting on cinderblocks. A bank of television monitors sat upstage, showing an array of sequences from nature films, surgery films, Hollywood war movies and sometimes infomercials.

The three-member cast is headed by Smith, a lean and sardonic fellow who led with a lengthy, amusing monologue. The talk was loosely about war — his father and grandfather were in the service — but was frequently interrupted by calls to his cell phone, purportedly about casting opportunities for Smith himself.

However, about halfway into the two-hour show, the scenario began gradually to transform from this engaging setup into a nightmarish, nonlinear war story, from train-up to an invasion/occupation sequence in which Smith was joined by two young actresses portraying residents of the invaded country.

The evening’s keynote motif was an extended riff on The Iliad, our oldest literary epic about war. Along the way — and as Smith shifted in and out of various personas — audience members were conscripted to be Greek gods, fellow soldiers or even just people asked to memorize a single word. Much of the second half, moreover, took place in a menacing near-dark, with flashlights and other small onstage lights the lone illumination.

Measure Back is not “anti-war” in the usual sense. Smith and McElroen, longtime collaborators who devised this work together, want us to ponder what impulses lead us toward war — and maybe to feel some of them ourselves.

Meanwhile, the work’s female characters — a motif of veiling suggests Iraq, Afghanistan — told of oppression that one might wish to go to war to oppose. Yet the play also explored the links between misogyny and violence; one clever, Carlinesque sequence deconstructed the English slang conventions that make it a compliment to call a woman “dude,” but an insult to call her the name of a female dog.

That thread came to a point with running commentary on Helen of Troy as the supposed cause of the Trojan War. “I think Helen was just the story they told,” Smith said. “They wanted Troy.”

But the link between the practice of acting and the making of war goes beyond the Hollywood Helens flickering on those monitors, and even beyond Smith’s rips on the acting profession. Much of the audience interaction, for instance, was built around brief interactions in which Smith affixes blame or demands loyalty to his cause, forcing audience members into false choices, and demanding that people make snap, life-or-death decisions in the madness of a moment, sometimes, while literally in the dark.

Though it feels a bit longer than necessary, Measure Back is bound to provoke discussions about its meaning and intent. What it suggested to me is that, as if we were all unconsciously actors, we humans tend to play the roles expected of us. And if we are expected to engage in, or support warfare, we too often will. 10.23.2013

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Bob Hoover – As if we needed another reminder that war is hell, the audience for the Festival of First’s drama “Measure Back” began the two-hour evening sitting on cement blocks. It might have been too literal to begin with, being staged in the Baum Building, once the office of a well-advertised Pittsburgh dentist and inspiring a schoolchild joke from the 1950s:

“Did you hear there was an explosion Downtown?”

“No.”

“Dr. Baum fell out a window.”

There were plenty of recorded blasts during this reworking of “The Iliad,” with its confrontational approach that insisted the audience pay attention to the details and moral issues of war, whether it were the Greeks vs. the Trojans or the daily conflicts of the 21st century.

The night began quietly with a monologue by actor T. Ryder Smith, who partnered with Christopher McElroen to assemble a multimedia play using the poetry of Homer to illustrate that little has changed since the Greeks set sail to retrieve Helen.

Opening with jokes and personal patter, Mr. Smith abruptly challenges the audience with a hail of provocative questions, now and then bringing a few members up to cast them in various roles or give them little tasks. Yet, as we moved from our blocks to folding chairs and Mr. Smith from a suit to soldier’s fatigues, “Measure Back” lost some of its in-your-face bite as it changed into a more traditional play.

Dionne Audain and Felicia Cooper joined Mr. Smith in a series of scenes focusing on how women are brutalized in war as the man, using a cliched Southern accent, threatened them. In turn, the actresses created effective scenes of tenderness as they shared their common plight.

“Measure Back” seems still a work in progress as themes are uncompleted or explained in heavy-handed ways. The actors, however, are powerful, threatening and sympathetic despite a complicated script and frequent audio and visual distractions.

Be prepared, then, for a physical and emotional workout. “Measure Back” demands that you squirm uncomfortably, standing or seated, so take pains to be ready for it. 10.24.2013

Etudes Journal, David Bisaha – Audience Participation as Consumption and Citizenship in Contemporary Storytelling Performances of The Iliad. Abstract: As American military actions in the Middle East continue, the Trojan War has become a useful text for exploring the emotional landscape of war. In this article I contrast audience engagement strategies in two storytelling performances of The Iliad, 2012’s An Iliad and 2013’s Measure Back. Both productions use the Homeric epic to link ancient and modern war, yet their methods for framing audience agency differ sharply. An Iliad attempts to create shared responses of ritualized mourning through realistic, individualizing techniques, while Measure Back cultivates independent spectator‐citizens by provoking immediate, emotionally uncomfortable reactions and encouraging judgment of fellow audience members. By applying Gareth White’s concept of “horizons of participation,” developed in his study of immersive and participatory performance, I argue that the style of audience engagement offers an opportunity to reflect on the agency of the individual citizen. Interactive audience strategies highlight the performativity of citizenship—you are shaped by what you do—whereas a realism‐based mode tends to reduce citizenship to consumption: the spectator as consumer of the actor’s emotional labor rather than co‐participant in historical meaning‐making. While neither production fully develops viable political interventions outside the theater, the participatory techniques of Measure Back constitute a strategy for developing individual agency through dissensus, and uncover implicit assumptions of passivity and affective consumption on which An Iliad is based.

Contemporary retellings of The Iliad have been of interest in regional and experimental stages recently. While the backdrop of American war in the Middle East has animated stage interpretations of the Greek epic and tragedies since at least September 11, 2001, 1 fatigue from extended military exertion abroad has made the Trojan War in particular more relevant. In the two performances I consider, The Iliad is both an expression of the emotional spectrum of soldiers at war – the rage of Achilles, the defiance of Hector, the love of Patroclus, the grief of Priam – as well as a prototype through which one understands future conflicts. This essay finds that storytelling performances of The Iliad provide opportunities for developing views of citizenship. For these purposes I define citizenship as the ability and responsibility of the individual to make and be accountable for political change. Through an analysis of the performances’ approaches to audience participation, I argue that interactive strategies highlight the performativity of citizenship, while a traditional, passive spectatorship 2 tends to reduce citizenship to consumption: the citizen as consumer of entertainment commodities rather than a participant with political agency. Despite a recent popular and scholarly trend to see citizenship and consumption working in concert, 3 I sustain an opposition between the two in order to highlight ways in which the acceptance or challenging of typical American theater spectating paradigms can prompt or deaden political calls to action within the Trojan War story.

A similar scenario grounds 2012’s An Iliad 4, developed by Lisa Peterson and Denis O’Hare, and 2013’s Measure Back, by Christopher McElroen and T. Ryder Smith. 5 Both riff on The Iliad, filtering portions of the epic through an ahistorical, ironic storyteller. These storytellers bring the audience up to date with current‐day references. For example the Poet, the only performer in An Iliad, translates the Greek alliance’s places of origin into a list of American regions and dramatizes the sunk‐cost fatigue of prolonged war by comparing it to a supermarket check‐out line.6 The effect is disarming yet striking when the Poet applies the same direct language to deaths of Patroclus and Hector. By contrast, Measure Back’s narrator (played eponymously by performer T. Ryder Smith) challenges the audience to directly confront wartime emotions, not as an aestheticized past event but by structuring fictionalized experiences in order to provoke anger, pathos, and contempt. In this way Measure Back searches for the origins of war (to “measure back”) within the audience members themselves. Audience members stand, speak, vote, and resist. The contrast between these audience engagement strategies delineates two possible responses to war. By structuring audience responses toward war, these productions include “horizons of participation” that gesture toward political engagement, but stop just short of achieving it.

The two performances drew on markedly different audiences. An Iliad was developed within the nonprofit theater model, and after a successful New York off‐Broadway run is now performed in regional theaters, universities, and community groups. Measure Back began as a festival performance, has had only two weeks of runs in Pittsburgh and Durham, NC, and has kept McElroen and Smith at the helm. 7 One is a virtuoso performance event, while the other cultivates a workshop sensibility. As a result, the creators’ expectations for audience behavior differed greatly. To conceptualize this difference, I draw on what Gareth White has termed “horizons of participation.” For White, a horizon of participation is “an initial assessment of the potential activity appropriate to the invitation…the horizon is a limit in the sense that it stands for the point at which we recognize invited and appropriate action ends, and inappropriate responses begin.” 8 Placed in the context of the historical epic, the horizons of audience participation delineate a set of acceptable, expected responses to war emotions. On a basic level, An Iliad promotes a silent, emotionally receptive audience, while Measure Back requires audience members to publicly rationalize choices in confrontational moments. Whereas An Iliad emphasizes communal consensus in ritualized aspects of mourning and hope, Measure Back uses the same source material to simulate political dissensus, encouraging inter-audience and audience‐performer conflict in full view of others. These productions contrast most strongly in these “expected” responses. In one, the audience member consumes individually; in the other, the audience member contests publicly. Both productions pose the same question: what, if anything, can the individual do in response to war violence?

The conceptualization of performance as an affective experience to be consumed is strong in American commercial and nonprofit theater. In her consideration of arts marketing and its effect on audience expectations, Lois Foreman‐Wernet argues that consumption and citizenship are competing artistic goals. Marketing irreparably tilts the balance in favor of seeing the art object as a consumer good. 9 For Foreman‐Wernet, marketing conceptualizes the art object as a consumable good, and not a public good, which makes engaging citizenship priorities secondary to market concerns. Applying the consumption‐citizenship binary to the Iliad productions underlines their differences. In the case of An Iliad, the primary experience for “sale” is a ritualized mourning process conducted by a virtuoso performance of a celebrity actor, all conceived as saleable commodities. A politically fertile, collective experience is further hampered by the assumption of theatrical tropes designed for individual consumption, such as the darkened audience and the raised, technologically augmented stage. By emphasizing personal affect in retelling The Iliad, Peterson and O’Hare have developed a reproducible commodity that produces a reliably affecting theater experience.

The structure and performance style of An Iliad prioritize accessibility. Peterson and O’Hare have selected a portion of the epic, focusing on the “rage of Achilles” from Agamemnon’s seizure of his war‐ prize bride Briseis to the return of Hector’s body out of compassion for Priam’s grief. The selection transforms the story of the Trojan War into a simpler narrative of rage, revenge, mourning, and mercy. The Poet stops the narrative after Hector’s funeral, avoiding the death of Achilles and the siege of Troy: “I don’t want to tell you what happens next…you know what that’s like, the death of a civilization.” Throughout the performance, which shifts from the Greek camp to the home life of Hector, from playful impersonation of the gods to direct translation of ancient conflict into contemporary terms, the Poet emphasizes the emotional aspects of mythic figures. Smooth transitions from the words of the poem into contemporary, Americanized speech and from mimetic representation of he story to direct audience address place the Poet and the story “out of time,” easy to mentally transport to “now.” Design choices in the original New York Theatre Workshop production emphasize the timelessness of the production and ease the direct connection of the ancient past to the contemporary war. An empty theater space is filled with shabby Pirandellian props: a table, chair, a suitcase against a blank theater wall.

Among An Iliad’s most powerful dramatic tools is the recitation of a list of wars, in chronological order, connecting the Trojan War to Syria. 10 Memorably, after Hector’s death the Poet stops his storytelling and reflects on the “waste” of that “terrible hot day,” likening the death of Hector to the conquest of Sumer. No, he says, that’s not right, and he lists a series of new wars. It soon becomes clear that he is listing almost every major conflict. In some productions this takes upwards of ten minutes. Stunned and chastened, the Poet moans and returns to the story by narrating Priam’s request for his son’s body and the following Trojan funeral. The dramatic strategy turns the recitation of a war poem into an elegy, a ritualized lament for past and future war dead. Through O’Hare’s accelerating, tense delivery, 11 An Iliad eschews scenic spectacle and narrative ornament; the narration stops midway to focus on a penitential honoring of the dead. At this point, the audience has experienced the war‐ movie climax of the piece in Achilles’ defeat and humiliation of Hector, but not the fulfillment of Achilles’ acquiescence to Priam. The list is the rhetorical heart and emotional core of the play. Here the Poet makes his strongest case that war is not confined to myth or the past. The version of war seen in the classics stands in for the loss of all war, of all time.

The story and the list are addressed to an audience conceived as a single, feeling mass. The primary method for engagement with this story is affective, that is, one is meant to merge with other audience members as fellow mourners, but not necessarily as participants in the play’s action. Music underscoring the NYTW performance complements and guides audience response toward shared emotional responses. Emphatic, stark lighting and sound design similarly accented the Pittsburgh performance. In both the audience is always addressed as a collective, and text and spectacle reinforce the group experience of mourning for massive losses. Mourning is the primary process through which the inconceivable is made meaningful, yet the fatigued, nihilist approach the Poet takes (and the long list of conflicts) suggests that even he knows that stopping war through grief is impossible. The emotional catharsis experienced allows for meaning to be drawn from the immense loss, and for the hope, however futile, for a world that recognizes the cost of war.

Despite its powerful ending, An Iliad stops short of challenging the status quo. In its acceptance of dominant trends of mainstream theatrical production the audience remains politically disempowered as they are emotionally engaged. Mourning becomes a product for consumption, and the production exchanges cultural capital and a promise of catharsis for the price of admission. The performance is essentially tragic in structure, just as the Poet sees history; he casts humanity as doomed to repeat war. The cathartic release and the implicit expectation of empathic engagement with the story and the Poet reinscribe an American model of theatergoing grounded in tragedy and aesthetic consumption. The audience’s horizon of participation is to laugh, to cry, and to try to understand the Poet, to feel with him as he says that “every time I sing this song, I hope it’s the last time.” What is ultimately produced, nevertheless, is a cultural and emotional commodity, to be received on a personal level. Audiences are expected to feel similarly, yet singularly.

Measure Back cultivates participatory engagement by making passive spectatorship impossible. It does so by relying on improvised interactions between performers and one or more audience members. The production also includes monologues and extended dialogue sections inspired by The Iliad, such as when Patroclus details his friendship with Achilles, or when Smith playing an American soldier interrogates and captures Briseis, a local woman in an unnamed Middle Eastern town. 12 The portions of the performance that I focus on, however, are participatory “experiments” structured by Smith, designed to reproduce the emotions and split‐second reaction of war. At times, these experiments challenge audience members to defy Smith’s instructions, to imagine abusive or violent acts, or to view other audience members as possible victims or co‐ belligerents.

Measure Back is still a work “in process,” and not only because of its highly participatory nature. Between evenings of production and between the Pittsburgh (October 2013) and Durham, NC (November 2013) presentations, the performance was dramatically revised. Measure Back no longer exists in the form I write about, and has not existed in precisely this iteration since the first performance I saw on October 20, 2013. Correspondence with the creative team suggested that within the Pittsburgh run, audience participation in one evening was so strong as to alter the climax of the performance, events which led to later developmental changes in tone, the type of experiments used, and even the number of audience members “in play” at any one time. In 2014 development continued; the subtitle of the performance is now “a rehearsal for the end of war,” dropping both the “theatrical event” and “immersive theatrical environment” prominently featured in the marketing for its Pittsburgh iteration. 13 As a performance without a stable text, I explore the initial performance as a momentary artistic whole.

The audience sat on cinder blocks around a short, plywood thrust stage. The space contained piles of rubble, television screens, and power tools; I was given a brick at the door and selected a seat. The performance began with the narration of the beginning of the Trojan War: Smith explained the choice of Paris among the goddesses Hera, Athena, and Aphrodite. Once the war “started,” the linear story of Troy broke down into a series of provocative questions posed by Smith directly to specific individuals. “What would have to happen for you and me to be at war?” Each interaction tested the audience member’s capacity for obedience by restaging moments from myth. In one, Smith selected a “volunteer” and asked us to imagine horrible things – abducting, beating, disabling the volunteer – and then asked the volunteer’s date whether he was now “at war” with him. In another moment a man was asked to give a pillow to the richest person in the room. In a third, I was told to cut off my own hair. Given no implements, I hesitated, and then Smith declared me “dead,” along with two people next to me. Eventually, the mythic aspects of the confrontations became clear. Iphigenia was the women “sacrificed” in our minds, and the pillow‐sacrifice was meant to emulate the swearing of loyalty to an ancient king.

While the audience watched, a brief interlude transitioned the set into a “war zone”: the same space, darkened. Similar tasks were expected of us, though now the targets of the tests were two actresses playing local inhabitants. For example, one of the women wanted a drink, and was forced to hold ice over a cup until she had one. The other woman was leashed, and an audience member was instructed to hold on and prevent her from leaving. She begged to be let out, and in my audience the man relented; he was dressed down by Smith’s soldier character when he was found out. The production ended with a participatory twist on the choice of Paris. Each audience member had written the name of someone we loved on our brick. At the end, audience members were polled: do you choose Power (Hera,) War (Athena), or Love (Aphrodite)? Most audience members chose Love; perhaps this was an obvious choice, in retrospect, though single members chose Power and War. To make the choice, audience members stood, placed their brick on a makeshift altar, and moved to the back of the space. The performers pulled a plastic curtain, Smith took a sledgehammer to the bricks, and we were instructed to leave.

What to make of these experiments? It didn’t seem to be about consequences. It didn’t matter whether one complied or resisted the soldier’s demands, or whether you chose War or Love. The verbal abuse and material destruction appeared to be the same. What was most impressive was the demand placed on me that I make some public choice. These choices came to “define” me in the eyes of the other audience members, and theirs defined them. Holding the woman on a leash, or standing up for Power, came to define a temporary identity in distinction to the other audience members present. Rather than constituting an affective kinship among a singular audience, Measure Back broke up an audience into individuals, and forced them to perform choices which could have material consequences. I learned others’ obedience and resistance strategies; came to feel a complex mixture of empathy, pity, and guilt for imagining violence done to the woman playing Iphigenia; and felt anger at Smith/the narrator for having made me imagine such things. The performance individualized all interactions: “What would have to happen for you and I to be at war?” A network of relationships between individuals replaced the sense of the audience as a multiple mass and the performer as a producer of an affective commodity. Though I have no evidence of new relationships sustaining beyond the performance, empathic glances and hesitant actions signaled the shift from an unnamed group of fellow‐feelers to an active if temporary community. Within this community, individual responses were immediately seen and judged.

Here the horizons of participation are wide and ostensibly unregulated. That is, neither Smith‐the‐performer nor Smith‐the‐narrator provided the audience with explicit rules about what sort of behavior was expected or inappropriate. Being so open, the horizon was fuzzy at first, and audience members timidly responded. Through repeated interactions, however, Smith made it clear that any response would be interpreted as an interactive element, even non‐action. Obedient and subservient interactions prolonged the moment, while combative or reticent interpretations closed down the encounter. Was this simply the performer’s reluctance to engage with audience members who wouldn’t “play along,” or were we being conditioned to act? Indecisive actions were taken to be fully intentional responses by Smith and the other actors. After viewing the diverse responses from the audience members it became clear that, while horizons were technically open, the preferred response was to act with, but not to control, the encounter.

In prioritizing the moment of choice over the consequences of the action, Measure Back’s aesthetic agenda encouraged acting immediately and publicly rather than correctly or politely. Surrounded by representations of war environments from around the globe in the set and on video screens, the need to address gut responses to violence became clear. How much could our actions affect faraway conflicts? Local ones? Perception of agency is a part of the determination of a horizon of participation; as White notes, “the horizon that participants perceive maps out the possibility of their agency in the event.”14 While White’s discussion is limited to the perception of agency within the dramatic event itself, and the degrees of risk, pride, and guilt that can accompany interaction, Measure Back blurs the separation between the theater event and real‐life war. Media, contemporary references, and the attempt to recreate the emotions of wartime decision‐making propose that similar self‐limitations characterize political engagement with others outside of the performance context.

At the end of the production, the placement of the bricks constituted some degree of collective decision‐making, or citizenship. As we stood up for Power, War, or Love, leaving tokens on stage, the performance approximated voting. Having been through the tests of individual action, we were finally asked to make action together, though without obvious consequences for choosing one way or the other. As I have said, most of my audience chose Love, which resulted in destruction. In contrast to the type of collective unit assembled by more traditional theater forms, this audience was more strongly individuated. The people “voting” became defined by their fictive personas or their onstage actions, a public identity, which once shared with the group, came to blend with whatever other information I had: I recognized a few local actors and newspaper critics among us. In this way participatory performance became constitutive of a temporary but meaningful (semi) public identity, one which allowed me to contextualize the “votes” cast at the end of the production. Coming out of Measure Back I saw citizenship as performative, to invoke Butler. Just as repeated acts and gestures create and sustain gender identity, performance and especially participatory performance constitutes an idealized self through action. 15 The performativity of citizenship, or at least the creation of socio‐political identity within a group, was a highlight of a challenging performance. It provided some measure of hope for individual agency, if not the efficacy of the agency to stop war. At minimum it temporarily dislodged the consumption model of performance and opened up new agentic positions in relationship to an otherwise closed story of war, revenge, and violence.

The agency of individual choice and the need to modulate presentations of the self is much larger in participatory work. In An Iliad, the primary affective response works in a consumption model. The audience is conceived as collective and shared, yet relatively free of inter‐ audience performance evaluation; the production transforms negative affects into positive ones through the creation of a closed, cathartic narrative; and success is dependent on positive evaluation of a much‐ applauded virtuoso performer. Measure Back, by contrast, encouraged inter‐audience judgments and evaluations, harnessed negative affects as a part of the aesthetic experience without obvious cathartic resolution, and positioned the lead performer as audience antagonist. By seeing these two retellings of Homer’s epic as possible models for contemporary retellings, they throw each other into relief.

While I find Measure Back to be more engaging as a prompt for thinking about audience agency, they share some similar shortcomings. Neither production completely maps out effective political engagement, finally producing aesthetic judgment. (In the case of Measure Back, my aesthetic judgments were about the concept of agency itself.) There are also historical temptations; in a 2004 essay, Mark Grief points out that it is too easy to read the Trojan War into Iraq, in part because the archetype of the Greek hero seems apt for the American soldier, armored, protected by forces from above, singular, irreplaceable, visible. 16 According to Grief, the blanket application of the Homeric idea of war to military occupations of Iraq and Afghanistan is inappropriate. I agree that by judging our emotions by those of the ancients, measuring back to the beginning of war, we assume that war hasn’t changed. When these productions look back at the Trojan War, they expect to recognize themselves. Whether within the transhistorical humanism of An Iliad or the flippant, gritty tone of Measure Back, the Trojan War parallel fails in the details, and reduces the complexity of US involvement to tragic heroism.

By imagining a new world, and practicing action within it, do we start to create that world outside the performance? Is this effect limited to performances that label themselves as a “rehearsal for the end of war,” or might it apply to more typical theater fare? If affective consumption in An Iliad promotes cool aesthetic distance, is the active interaction of Measure Back truly liberatory? It seems to be “rehearsal for life” in a Boalian sense,17 but my performance was so heavily structured around expected nonaction that it became divorced from meaningful context or viable alternatives. Neither production bred political close‐feeling; perhaps we can only expect them to illuminate our current world, rather than light a better way forward. Nonetheless the increase in participatory audience experiences opens up new questions: with both traditional/realist and immersive/participatory approaches to war, can either move audiences to rehearse for action, to think beyond ourselves, and to move past aestheticized, packaged meanings of violent conflict? February 2015 issue, v. 1, n. 1

1 The most popular dramatic adaptation was Wolfgang Petersen’s 2004 film Troy, which Peterson has explicitly linked to American intervention in Iraq. More recently, Craig Wright (The Iliad, 2010) and Simon Armitage (The Last Days of Troy, 2014) have penned theatrical adaptations of The Iliad, both for larger casts. Ellen McLaughlin’s Ajax in Iraq (2008) and Charles Mee’s Iphigenia 2.0 (2007) are but two adaptations of Greek tragedy with Gulf, Iraq, or Middle Eastern war themes in mind. For more complete analysis of the use of Greek source material in contemporary war plays see Helene P. Foley, Reimagining Greek Tragedy on the American Stage (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012), and Edith Hall, Fiona Macintosh, and Amanda Wrigley, eds., Dionysus Since 69: Greek Tragedy at the Dawn of the Third Millennium (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004).

2 By “traditional spectatorship” I refer to the mode often employed in contemporary US, Broadway/regional theatre. Typically associated with realism, this style employs separation of audience from performance area, darkens the auditorium, and discourages interruptions and interaction between audience members.

3 “Consumption” and “citizenship” are commonly mapped onto binaries of passivity/activity and private/public, as Kate Soper and Frank Trentmann’s collection points out. This opposition is coming under increased scrutiny in the 21st century. For example, boycotts and “voting” through donation have become more influential in an age of social media and crowdfunding. See Kate Soper and Frank Trentmann, eds., Citizenship and Consumption (New York: Palgrave, 2008).

4 The first production of An Iliad was in 2010 at Seattle Rep, though the current version of the production produced widely in regional theatres draws from the New York Theatre Workshop production opening February 15, 2012.

5 I draw from the script of An Iliad as performed at the New York Theatre Workshop, personal experience of seeing a subsequent production at the Pittsburgh Public Theatre in February 2014, and archival video of a dress rehearsal featuring Denis O’Hare as the poet, available at http://vimeo.com/67930478. Measure Back is unpublished, and I rely on personal experience of seeing its first performance in Pittsburgh in October 2013, in the Pittsburgh Festival of Firsts, and correspondence with the artistic team. Some photo and video documentation is available on the artists’ website, http://measurebacktheplay.org/.

6 Charles Isherwood remarked that a chief characteristic of An Iliad was its “chatty, informal” tone of the Poet which “puts both mortals and gods on our own level.” Charles Isherwood, “Troy…um, War…You Know,” The New York Times, March 7, 2012. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/08/theater/reviews/an‐iliad‐at‐new‐york‐theater‐ workshop.html

7 Measure Back is still in revision/development. On October 13, 2014, an excerpt from a new version was performed at Dixon Place in New York City with new video elements, reduced scenery, and a revised participatory scheme.

8 Gareth White, Audience Participation in the Theatre: Aesthetics of the Invitation (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013): 59. The term “horizon of participation” draws on Hans‐Robert Jauss’s concept of “horizons of interpretation,” referring to the available interpretative options for a work of literature within a given historical time and place of reception, and further develops application of reader‐response theory to theater studies; notably, in Susan Bennett’s Theatre Audiences (New York: Routledge, 1997).

9 Lois Foreman‐Wernet, “Targeting the Arts Audience: Questioning Our Aim(s),” Audiences and the Arts: Communication Perspectives (Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press, 2010), 21‐42. Foreman‐ Wernet’s critique of these aims is specific to American theatres in which ticket sales and contributed income drive large‐scale, permanent producing organizations in the nonprofit model.

10 Subsequent productions have added later conflicts, including (in Pittsburgh, 2014) the conflict in Crimea. The list purports to include conflicts from all wars, not merely “major” wars from a Western frame of reference. O’Hare and Peterson constructed the list to oscillate between the recognizable and the unknown.

11 Other Poets have dealt with the list differently. For example, Teagle F. Bougere recited the lists very slowly in the Pittsburgh version, couching each name in silence, marking the death toll of each war.

12 Two other performers joined T. Ryder Smith in the Pittsburgh production, Dionne Audain and Felicia Cooper. The location of the invaded town was denoted by images of American military activity in a desert on upstage video screens, and was further suggested by a long, fearful monologue in Hebrew delivered by Cooper in the second half of the performance.

13 Publicity materials for Measure Back as part of the Pittsburgh International Festival of Firsts can be found here: http://culturaldistrict.org/production/38862/measure‐back.

14 White, Audience Participation, 60.

15 White extends Butler’s performativity to the constitution of self through performance participation: “If, as I have suggested, audience participation has a special capacity to be taken as a representation of the person performing, it might speak about this public identity in especially powerful ways – whether it speaks truths about it or not. Audience participation is another space where we take part in the performing/becoming of the self, and the risk we perceive is a risk to this idealized substantial self, to this pragmatic self, or at least to whatever version of it we are trying to promote.” White, Audience Participation, 106. See also Judith Butler, Gender Trouble and the Subversion of Identity (London: Routledge, 1999): 173.

16 Mark Grief, “Mogadishu, Baghdad, Troy; or, Heroes Without War,” n+1, No.1 (Summer 2004): 132‐150.

Theatre Journal, David Bisaha – What does it take to stop a war? Measure Back, a collaboration between director Christopher McElroen and writer/director/performer T. Ryder Smith, retells The Iliad in order to “measure back” to war’s origins. Like McElroen’s 2007 Waiting for Godot, performed and set in the Ninth Ward of New Orleans, Measure Back engages a community of spectator-citizens with transhistorical ethical dilemmas. Drawing from previous experiments in storytelling, media integration, and audience participation, such as Living in Exile (2011), McElroen and Smith problematized tacit acceptance of violence by requiring audience members to act and speak before forty other spectator-citizens. While recent immersive work has fetishized the one-on-one interaction, Measure Back argues that politically meaningful interventions must occur in public.

The piece is a series of performative encounters and Homeric vignettes. As I entered, performer Dionne Audain gave me a brick and chalk: “Write the name of someone you love.” I wrote my grand- mother’s name and sat on a cinder block facing a low plywood stage. Crates, televisions, piles of rubble, power tools, and military costume pieces dotted the space, while possibilities of torture and destruction loomed: a baseball bat, a sledgehammer, a looped video of apocalyptic prophecy.

After introducing himself, Smith began narrating the epic, assigning audience members roles in the action: a veteran was dubbed “Zeus”; a young woman, “Aphrodite”; and we all became attendant Olympians. Athena cast off her cloak of war, Paris gave Aphrodite the apple, and the Trojan War began. No single story was told in its entirety; rather, Smith and McElroen invoked the myth as a generative structure for direct, individualized challenges to our understand- ing of ethics, obedience, and violence. Throughout, Smith posed pointed questions with a drill sergeant’s impatience and demanded that we take immediate, sometimes impossible action. If someone did not stand quickly or respond correctly, he pronounced them “dead.” I stood when requested, but then was told to cut off my own hair. When I hesitated, Smith “killed” me, along with two audience members to my left. “Ask them how they feel about that.”

Other encounters demanded that we judge fellow audience members. One man was instructed to give two pillows to the richest person in the audience.

Later, Smith identified a couple and asked the man what it would take to start a war. He brought the man’s date onstage, blindfolded her, and asked the entire audience to imagine where they would hit her to make her “remember you forever.” The man, visibly shaken, agreed that he was now at war. Another young female audience member, “Iphigenia,” donned a veil downstage. Smith held up signs ranging from neutral (“girl”) to offensive (“bitch,” “meat”); we were to clap when he “crossed the line.” Uncomfortable, we obeyed.

Halfway through the production, the mood shifted from experimental to mimetic. With house lights dimmed, two actors emerged from shadows and the set became a foreign war-zone, under attack from “Greek” forces with US accents. Audain retreated when Smith brandished a power drill. A third actor, Felicia Cooper, fearfully delivered a long monologue in Hebrew. She and Audain (billed “Briseis 1 and 2”) hid from Smith, who enlisted audience accomplices in further confrontations. One man was told to keep a flashlight trained on Cooper to prevent her escape; when she eluded him, the “captor” was brutally insulted. Another held a leash tight around Cooper’s neck. Tension peaked, yet we fulfilled our tasks—did we have any other option?

The climactic experiment replicated Paris’s choice: Audain challenged us to make a stand (literally) for power, war, or love. At first, no one moved. Then I stood up for power and Audain brought me onstage. As I placed my brick on an altar, I turned to the audience, alone. In a powerful improvised moment, Audain asked me if I was embarrassed. I nodded silently, not quite sure if I was, and returned to my chair. An antagonistic, macho young man next to me stood for war, although he had been snidely resisting Smith’s authority all night. The rest stood for love—the right choice?—and stacked their bricks. We moved behind a thick plastic curtain and Smith took a sledgehammer to the pile. The wall fell and the performance ended, but my questions remained. For what does one take a stand? When? In front of whom? Is “standing up” all that it takes to stop a war, or just a seductive simplification?

The performance was not without shortcomings. Some narrative threads and participatory tasks were dropped. More disturbingly, the production traded in racialized and misogynistic language and scenarios, yet the critique of these attitudes was only implied. Relying so heavily upon The Iliad normalized its worldview, and the production often spoke to male spectators as peers, yet treated women as potential objects.

Smith claims that the production is devised each night based on audience participation, yet the structure felt predetermined. Could the audience reasonably resist? One might have left or spoken out against the misogynist Iphigenia episode, but Smith had both the power and seeming inclination to shut down protest. My audience was silenced, shamed, passive. Ultimately, Measure Back is driven by the hope of individual empowerment, yet I questioned whether such goals are attainable. Perhaps my audience simply did not have anyone brave enough to radically resist. Smith has indicated to me that subsequent audiences varied widely, and that future runs of Measure Back will further develop improvised audience confrontations. This time, I left feeling that war cannot be stopped.

In the following days, however, I recognized fellow audience members in other locations. I mostly remembered those who had acted: Iphigenia; the leash-holder; the man who “went to war.” I wondered if I was now “the one who chose power.” Measure Back reminded me that even within audiences, actions speak loudest. The production risked ethical violations and forced immediate confrontations with potentially unattractive aspects of ourselves, but doesn’t challenging a detached relationship to war demand such immediacy? Measure Back may not have empowered this audience to stop violence, but it did change our perceptions of one another, from consumers of art to potential agents of war— or, perhaps, peace. October 2014 issue, v. 66, n. 3

The Five Points Star blog, Kate Dobbs Ariail – I’m old. It’s definite now. I don’t have to ask the mirror anymore. I was chosen as someone who looks old–though not rich, Jewish, or like a terrorist–by a complete stranger last night during Measure Back, an “immersive” theatre-event that depends heavily on audience participation and manipulation. Presented jointly by Duke Performances and Manbites Dog Theater, the three-actor show, written by T. Ryder Smith, featuring him, and directed by him and Christopher McElroen, plays at Manbites through Sat. Nov. 9.

Perhaps it is my age that made me feel that Measure Back is a shallow thing. It’s about war–its history and its present; its whats, hows and whys, and what provokes us to it. This is hardly a new topic, but it is always laudable when artists and thinkers confront it anew. When they attempt to plumb its depths, we are harrowed and harried past our previous endpoints of thought and feeling, as we’ve seen locally in the past couple of years with Ray Dooley’s performance in An Iliad, and Ellen McLaughlin’s extraordinary Penelope at PlayMakers. Smith also uses The Iliad as source material–although he often seems dismissive of it–but he stays determinedly in the bloody shallows as he attempts to link that ancient tale to modern lives.

The games he, as The Actor, plays with the audience, along with The Actress (Dionne Audain) and The Other One (Caitlin Wells), are surely meant to make the dilemmas that lead to war, and war’s subsequent horror, more real to the audience–to literally force us to confront terrible choices. But, oddly, they have the opposite effect. The Actor often treats the audience members with condescending contempt, and there are never any painful consequences to the little set-ups, which give way at ADHD speed to something else, or else drag on murkily far past the point one cares to try to understand them. There’s no character we can latch onto, no story through-line, except in a rather esoteric sense. There is plenty of discomfort, beginning with the dismaying moment you walk into the theater and see that all the seats have been replaced with cinderblocks, except for a few folding chairs behind a sign marked “out of order.” There are periods of very loud noise; there’s lots of fake blood and gore and the miming of barbaric tortures, the worst of which is a prolonged rape scene involving a power drill.

But none of this causes any discomfort in the soul–at least, not of the kind that might provoke one to a more careful moral philosophy or a mordant understanding of the great human tragedy called War. The mental discomfort is purely aesthetic; the mourning is for the failure of a valiant effort of Art. 11.7.2013

CVNC.org, Jeffrey Rossman – Duke Performances, under the visionary leadership of Aaron Greenwald, continues its foray into collaborative ventures with the Durham arts community by jointly presenting Measure Back at Manbites Dog Theatre’s downtown venue. Both presenters give and get in this partnership. For Duke, it gets access to an intimate space for smaller, experimental theatrical events without the angst accompanying travels to Duke’s West Campus. Manbites Dog, in turn, benefits from both the cachet of the Duke name and its partial financial support.

I’ve regretted being a relative latecomer to Manbites Dog Theater and the inventive, creative and cutting-edge theatre that they have presented for twenty-five years. I have come to know that no matter how experimental, out-of-bounds, unusual, or just plain weird that the topic and script are, I can rely on a first-rate production that exemplifies artistic ethics and respect for its audience. Well, with T. Ryder Smith’s Measure Back, that glorious hitting streak has ignominiously ended.

Measure Back, the creation of OBIE (Off-Broadway) Award-winning director Christopher McElroen and Drama Desk Award-winning actor T. Ryder Smith, is ostensibly a rumination on war and an attempt to have an interactive experience with the audience to facilitate examination and understanding of just what is in the human DNA that makes us warlike people. Its press release as a mixed media theatrical “event” (not quite sure what that word adds, but it was used a lot) with three actors and some audience participation sounded quite promising, and certainly on the low end of experimental. But, for more than two intermission-less hours, I endured a half-baked, meandering, narcissistic exercise by Mr. Smith that not only did not answer any questions, but failed even to ask them in any meaningful or cohesive manner.

Upon entering the black box space, I was greeted by Dionne Audain, a well-respected actress with a long list of film and TV credits who would later appear in the play. She handed out an actual brick and asked me to write the name of someone I love on it. That was not the end of the brick theme. Except for a roped-off, forbidden area with standard folding chairs, the only place to sit was on cinder blocks. If you objected, you were grudgingly granted a chair. Mr. Smith came out, and while washing his face in a white bucket and changing clothes, he proceeded to tell us all about himself. That was the problem right from the start. In the end, Measure Back is all about him – I don’t mean the character in the play, but T. Ryder Smith himself. Despite his formidable and versatile acting chops, I couldn’t get past the fact that it practically screamed “ME, ME, ME!” Yes, I know this was meant to obliterate the actor/audience divide, but it did nothing to further the stated goal of the play: why does war happen and are we all complicit?

Next, audience members were randomly chosen and asked to pick others who, not necessarily in this order, looked like they had a lot of money, looked old, looked gay, looked Jewish, looked like terrorists, etc. No, I’m not kidding. It was interesting to observe Smith’s interaction with a man who simply refused to participate. This group of people was then permitted to sit in the real chairs. What does that mean? Dunno.

Much of this “event” (admittedly still labeled a “work in progress,” so I suppose I should cut it some slack) was based on The Iliad by Homer, as both the first work of Western literature and a manual of war. Was it still supposed to be funny the fifth time Smith “mistakenly” read from a Greek pornographic novel instead of the Iliad? We then endured a way too long section, in near darkness, where The Other One, played by Caitlin Wells, intoned some ancient language translated into college dorm wisdom. Then we went to the other extreme with flashing lights, explosions, and Smith, in camouflage fatigues, screaming nearly unintelligible tirades.

Much was made of Smith’s questioning of (some) frightened audience members about whether they could kill someone else, who realized (drum roll, please) it’s not that easy. Some audience interactions bordered on the abusive, and while that might be forgiven in a more successful effort, here it was ugly and mean-spirited.

There was also much made of this being a multi-media event, but the bank of five TV monitors at the back of the stage was underused and seemed superfluous. I entered with high hopes, because this “event” deals with serious, if ultimately unanswerable, questions, and the concept was quite enthralling. I genuinely kept waiting for it to be worth it, but as it hit the two-hour mark, it never happened. In the end, I was totally consumed with boredom and stuck in a room with a meandering morass of smugness. Whether that was a character in the play or the actual actor, I still cannot say. 11.6.2013

[previous] [next]