Photos by Marcus Stern

Above, from top, l to r: T. Ryder Smith, Therese Plaehn, David Chandler, Remo Airaldi, Michael Rudko; ensemble; T. Ryder Smith; Therese Plaehn, Cameron Oro; Karl Bury, Therese Pleaehn, Thomas Derrah; Sally Wingert , T. Ryder Smith; T. Ryder Smith; same; Merritt Janson, Karl Bury; Jonathan Epstein, Adrienne Krstansky; ensemble; Therese Plaehn, David Chandler, Sally Wingert; T. Ryder Smith, Therese Plaehn, Hale Appleman; Sally Wingert, T. Ryder Smith; Adrienne Krstansky, Therese Pleaehn, David Chandler, T. Ryder Smith, Jonathan Epstein; Therese Pleaehn, David Chandler, T. Ryder Smith, Jonathan Epstein; David Chandler, T. Ryder Smith, Jonathan Epstein; Therese Plaehn.

Excerpts from the reviews

Full reviews are below

“Hard times breed masterpieces, and nobody turned coal to diamonds like Clifford Odets. His “Paradise Lost,” penned 75 years ago, is the kind of play that shocks with its contemporary relevancy. . . . The production unfolds hugely and vibrantly on the Loeb Drama Center’s panoramic stage. . . . Odets invented his own language for this play – a combination of slang that sounds like poetry and poetry that sounds like slang. His characters talk streetwise, but have a professorial knowledge of American social history. . . . The A.R.T.’s production is bolstered by a fantastic cast – actors who are equally tuned into each other and Odets’ stylized mode of speaking. Fish means for these people to be mundanely monumental, and they are. Performing a frantic, off-the-cuff rendition of “Springtime in the Rockies,” Appleman’s Ben is the very spirit of bottled-up youth. Derrah and Chandler strike a compelling counterpoint as dwindling fathers, and T. Ryder Smith grabs our attention in an arresting dual role. . . . There are times when Fish holds the audience at arm’s length, and others where he grabs us by the collective collar and shakes hard.” Jenna Scherer, Boston Herald

“A night of theater that requires an investment, but delivers a very satisfying reward. . . . Director Daniel Fish brings a kind of existential approach to the whole thing. This isn’t America 1935; it’s America Anytime. The cast delivers its lines with an eerie detachment, as if the family’s slow slip into economic oblivion is an out-of-body experience. . . . The set and the delivery are so sparse that they don’t give you much to hang onto — it’s an unsettling experience that nicely mirrors the feelings of the characters onstage. . . . But there’s an impressive momentum to the show. The worse things get, the more human the play becomes. . . . The play becomes a compelling family portrait that details the ravages of economic loss. They aren’t ripples through a family; they’re shock waves, breaking apart everything in their path. Relationships are pulled asunder, husbands and wives, business partners and lovers all pay the price. Odets’ most poignant observation may be that, in times of loss, the thing that honorable people cling to is their dignity, and, during an economic freefall, that’s not nearly enough.” Alexander Stevens, Cambridge Chronicle

“Director Daniel Fish swallows this powerful depression era drama by the great Clifford Odets into a yawning abyss of negative space, silence, postmodern distancing techniques, and pretentious theatrical effects. . . . If you drink some caffeine, crane your neck, squint your eyes, and ignore the strange meta-narratives, you might pick up the story . . . ” Jason Rabin, Blast magazine.com

“A muddled, pretentious mixture of inexplicable technology, estranging effects, and bizarre sermonizing that overshadows the fine actors and even the story itself. . . . Any meaning Fish achieves with the present-day setting is negated by the baffling stark and technological aesthetic he forces on the show, which works against the script rather than with it. Videos projected onto a gigantic screen throughout the production are particularly off-putting. Even when the video works in a technical sense, it is distracting, unnecessary, and alienating.” Ali L. Leskowitz, The Harvard Crimson

“The production underscores the themes of the play in straightforward ways, but also in a manner that Odets may have found amusing: by projecting video on the rear wall, director Daniel Fish has found a means to emphasize certain moments . . . and to set the play against a literal backdrop of human suffering, happiness, or profit-driven conspiracy. . . . But the use of projection serves also to cast a certain skeptical tone into the play’s central argument. The first scene shows the final moments and end credits of a movie; the family, at the dinner table, are caught up in it, like any contemporary family gazing at the television instead of engaging with one another in conversation. Seen as a bookend to the soaring speech that Leo makes at the play’s end–in the very pitch of extremis, his home and family tottering toward oblivion–this introduction asks us the crucial, if difficult question: are such high-flown visions of humanity’s grand future enlightenment mere illusion, as dazzling but as fake as any dream projected onto the silver screen? Have we made a faith out of our faith in our own better angels? . . . Though the play is set in the 1930s, Lieberman’s set mixes props and furniture from several subsequent decades: the 1960s through the 1980s. If the Gordons’ home represents America, and their extended family embody all of us, then the few years the play encompasses stand in for what looks right now like an 80-year-cycle of poverty, aspiration, prosperity, and collapse. . . The play is long, its style and pace from an earlier era, but its tone of outrage is contemporary.” Kilian Melloy, Edge Boston

Rehearsal

Publicity

Full reviews

Boston Herald, Jenna Scherer – A.R.T. revives a vibrant ‘Paradise’. Hard times breed masterpieces, and nobody turned coal to diamonds like Clifford Odets. His “Paradise Lost,” penned 75 years ago, is the kind of play that shocks with its contemporary relevancy.

In that spirit comes Daniel Fish’s stylized, urgent revival at the American Repertory Theater. The “bust” portion of artistic director Diane Paulus’ “America: Boom, Bust, and Baseball” season, “Paradise Lost” unfolds hugely and vibrantly on the Loeb Drama Center’s panoramic stage.

It’s the early 1930s (in script, if not in costume) in Anycity, USA, and one any family is starting to feel the pinch of the Great Depression. Patriarch Leo Gordon (David Chandler) steers by his ideals, but they’re not going to save his floundering handbag factory.

Leo’s wife Clara (Sally Wingert) is just trying to hang on, while his business partner Sam (Jonathan Epstein) is finding less-than-kosher ways to make ends meet. Things look bleak, but that doesn’t stop son Ben (Hale Appleman) from marrying his sweetheart. And it doesn’t stop family friend Gus (Thomas Derrah) from chatting away the livelong day. Odets follows Leo, Clara and their brood out of the Eden of middle-class certitude and into the great impoverished unknown.

A lot of people do a lot of talking in “Paradise Lost,” but perhaps the most arresting voice is that of Mr. Pike (Michael Rudko, in a stirring performance), the socialist-leaning furnace repairman. He closes the first act with a soliloquy so fresh and eloquent, it sends waves into the audience.

Odets invented his own language for this play – a combination of slang that sounds like poetry and poetry that sounds like slang. His characters talk streetwise, but have a professorial knowledge of American social history. This is beat poetry written a generation before Jack Kerouac ever bared his guts at a jazz club.

Though the script sets the play clearly in the 1930s, Fish dresses the ensemble in modern clothes. But with talk of the nation’s fall from economic grace and unnecessary foreign wars, we don’t need the wardrobe hint to clue into the fact that the problems faced in “Paradise Lost” feel all too current.

Andrew Lieberman’s set looks like a Home Depot, all unfinished wood and unattached doors. It sends the disquieting message that the Gordons aren’t just losing their home – they never even built it to begin with.

The A.R.T.’s production is bolstered by a fantastic cast – actors who are equally tuned into each other and Odets’ stylized mode of speaking. Fish means for these people to be mundanely monumental, and they are. Performing a frantic, off-the-cuff rendition of “Springtime in the Rockies,” Appleman’s Ben is the very spirit of bottled-up youth. Derrah and Chandler strike a compelling counterpoint as dwindling fathers, and T. Ryder Smith grabs our attention in an arresting dual role.

There are times when Fish holds the audience at arm’s length, and others where he grabs us by the collective collar and shakes hard. Not every stylistic choice sings, but enough do so that you’re glad for Fish’s point of view. The overall effect of “Paradise Lost” is electric, shaking our winter slumber to awaken the untapped potential of the human spirit. 03.05.2010

Boston Globe, Louise Kennedy – ART’s ‘Paradise’ gets lost. Staging steals clarity from Odets’s heartfelt story of a struggling family. Somewhere, under the giant video screen and the equally oversize yet curiously flat concept that controls director Daniel Fish’s production for the American Repertory Theater, Clifford Odets’s play “Paradise Lost’’ is struggling to get out. But the text, like the hardworking men and women it portrays, is playing with the deck stacked against it.

How, after all, can mere words compete with gargantuan images, or characters with icons? If a video projection of two faces in closeup looms over the stage, who can look instead at the small human beings beneath it? Perhaps Fish means for his humans to look tiny, helpless, adrift in a world too big and cold to let them thrive. But that would be an awfully literal-minded way of getting at Odets’s themes.

Not that Odets can’t be fairly obvious in his statements himself. Born of the Group Theater of New York in the 1930s, Odets blazed to fame with “Waiting for Lefty,’’ “Awake and Sing!’’ and “Paradise Lost,’’ which he pronounced his favorite, all full of big speeches on big themes, speeches designed to stir his audiences to action.

But Odets always grounded his big politics in real human characters; if he was talking about “the little man,’’ he never belittled that man by reducing him to a prop on a larger stage. His characters, with their distinctive street slang, their quirks and dreams and failings, are theatrical creatures, yes, but also truly human beings. He meant for us to love them as well as observe them.

In Fish’s hands, however, the interwoven families of “Paradise Lost’’ look more like a colony of ants (and anachronistic ants at that, with Odets’s Depression giving way to some vague modern world that has video while radio is still a novelty, and cellphones for people who remember 1912). The director has them all start out onstage, around a big table; the ones who don’t happen to be in the first scene as written just sit there, waiting for their first line. Such manipulations continue throughout, with actors sitting off to the side, at the back, or even center stage as they wait their turns.

For those who know the play, it’s distracting and sometimes contradictory; for those who don’t, it must be nothing short of bewildering. Having several actors double in roles – and switch from one to the next without warning – only adds to the confusion.

Confusion often seems to be the point, however, as when we’re forced to watch those videos while attending to live action. OK, we get it, modern life is alienating. Odets himself found more subtle and interesting ways of leading us to the same conclusion. All we get here is the alternation of images that rub against the grain of the scene with other images that drive home its point all too literally.

What makes this especially frustrating is that, under the screen, a number of strong performances are taking place. David Chandler is quietly touching as Leo Gordon, the dreamer and paterfamilias who’s more or less at the center of things, and Jonathan Epstein counterbalances him perfectly as Leo’s dangerously pragmatic business partner, Sam Katz. Thomas Derrah, though an odd casting choice for the rough-hewn family friend Gus, is always amusing – until he’s achingly sad at the end – and T. Ryder Smith makes the younger Gordon son, Julie, an appealing enigma.

Troublingly, however, each of them seems to be in a separate play from all the others and still further separated from the people onscreen, even when those people are their own videotaped selves. The mild irritation this conceit provokes turns deeper in one sequence, when a delegation of workers comes to demand a raise. Fish chooses to stage this by having several actors, unseen, speak the lines while a previously recorded video, of assorted people speaking other, unheard words, stops and starts in rough synchrony.

Only from reading about the production do I know that these recorded people are ordinary people approached on the street in Troy, N.Y., and asked to talk about loss. Whatever they said, you’ll never hear it at the ART.

For Clifford Odets, who devoted his professional life to giving voice to the voiceless, it’s hard to imagine a stranger and less appropriate choice.

Cambridge Chronicle, Alexander Stevens – It’s worth a visit to Paradise. The American Repertory Theatre has dug up a buried treasure called “Paradise Lost” and spiffed it up quite nicely. It’s a night of theater that requires an investment, but delivers a very satisfying reward.

Time hasn’t been kind to playwright Clifford Odets. His contemporaries — Eugene O’Neill, Tennessee Williams and Arthur Miller — shined so brightly that they perhaps obscured Odets and his work. As a result, Odets is rarely in the same conversation with those greats, but after this spare and eloquent ART production — playing through March 20 at the Loeb Drama Center, in Cambridge — you may want to put him there.

But it’s a slow start. Director Daniel Fish brings a kind of existential approach to the whole thing. This isn’t America 1935; it’s America Anytime. The cast delivers its lines with an eerie detachment, as if the family’s slow slip into economic oblivion is an out-of-body experience. The presentation may remind you of the last scene in “Our Town.” They’re already dead.

The set and the delivery are so sparse that they don’t give you much to hang onto — it’s an unsettling experience that nicely mirrors the feelings of the characters onstage. (The large video projections that Fish incorporates are about as effective as video always seems to be on stage — not very.) But there’s an impressive momentum to the show. The worse things get, the more human the play becomes.

At the center of it all is the Gordon family. Dad (David Chandler) is watching uneasily as profits dwindle at his company. And he’s got more bad news coming from his business partner, Sam (Jonathan Epstein). Soon the Gordons will be wondering if desperate times call for desperate measures. A family faced with losing it all will consider anything. And Kewpie (Karl Bury) hovers, a constant reminder that, contrary to the pacifying bromides we’re spoon-fed, sometimes crime does pay, at least in the short term.

The play becomes a compelling family portrait that details the ravages of economic loss. They aren’t ripples through a family; they’re shock waves, breaking apart everything in their path. Relationships are pulled asunder, husbands and wives, business partners and lovers all pay the price. Odets’ most poignant observation may be that, in times of loss, the thing that honorable people cling to is their dignity, and, during an economic freefall, that’s not nearly enough.

The play has been criticized for being too didactic. Odets was, no doubt, a good socialist, and he works up a nice little anger about the fact that economic crises like those of the 1930s and today aren’t blips, they’re systemic. And, yes, we still have Mr. Pike (Michael Rudko), a kind of Greek chorus, or red chorus, as commie-phobes might tag him, who’s prone to little diatribes that explain what the play is about, just in case you weren’t following closely enough. But mostly Fish’s production does a good job of tamping down the rhetoric. He keeps the focus on the family, and watches the way we crack and peel in the crucible of humiliating loss.

It’s an ugly sight, a putrid smell, and we’ve all gotten more than a whiff of it in the past two years.

You may also marvel at the glory days of American playwriting — “A Streetcar Named Desire,” “Death of a Salesman,” and “Long Day’s Journey Into Night” all written within a decade of each other. Today, it’s kind of chic and easy to kick America when it’s down. But back then, Odets and company were on the edge, the voice of the disenfranchised. It’s thrilling to consider a time when playwrights were relevant social commentators. Today, their role has been usurped by TV, talking heads and other unsatisfying alternatives. This ART production may remind you that the death of art-and-comment onstage is another loss we’ve all felt. 03.05.2010

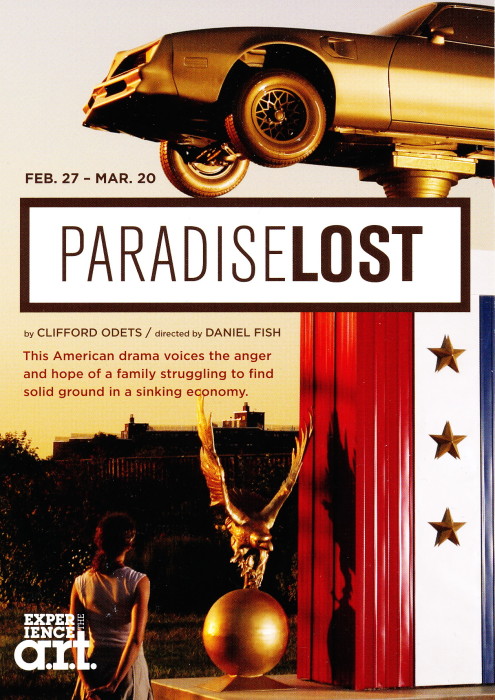

Broadway World, Nancy Grossman – ART dusts off Odet’s Paradise Lost. The American Repertory Theater presents Clifford Odet’s drama Paradise Lost as the second entry in its “America: Boom, Bust, and Baseball” festival. Set during the Great Depression, the 1935 play about the struggling middle class in an unidentified American city, conveys both the hopes and despair of the Gordon family and their extended circle as they teeter on The Edge of economic catastrophe and strive to find their balance in an uncertain world. Themes of social responsibility, self-interest, trust, loss, and governmental accountability provide the play with the trademark heft and depth of Odets, one of the defining American playwrights of the 1930s.

A director known for his innovative interpretations of classics, Daniel Fish is not new to the works of Odets and recommended Paradise Lost to Artistic Director Diane Paulus as the “bust” piece for the festival. By focusing on the human aspects of the play and making it happen now, Fish strives to overcome the challenge of freshening material that is seventy-five years old. He and his designers utilize an abstract stage construction of crisscrossed slabs and planks, a combination of harsh and dimmed lighting, and modern dress, including t-shirts bearing recent political slogans, to bring the production into the 21st century. What you won’t see are pieces of overstuffed furniture or accoutrements reflective of comfort and success. Props that are given prominence include daughter Pearl’s piano keyboard, the motorcycle of family friend Gus, and a large bronze statue of son Ben, an Olympic track champion.

As a member of the avant garde Group Theatre in New York, Odets emphasized ensemble work. For today’s theatergoer, it may take a little getting used to the format at the top of the show when more than a dozen people are sitting around a table having a conversation, no one character seeming more central than the next. Eventually, their interconnectedness is made clear, dramatic arcs emerge, and their stories are cogently woven together throughout the course of three acts, but Odets’ language is often more poetic and opaque than modern discourse, leading to a considerable amount of head-scratching about the meaning of some scenes. The accomplished cast contributes several worthy individual performances, but is missing the cohesion necessary for the ensemble to gel. Speeches frequently sound like soliloquies, rather than dialogue between parties, diminishing their emotional impact.

Paradise Lost tells a timeless and universal story, to be sure, but the contemporary treatment it receives at the A.R.T. didn’t work for me. Fish intends to make the play vivid and spontaneous by the insertion of video, but it is a mixed bag. When business partners Gordon and Katz are speaking with disgruntled union workers represented on the screen, it gives the tension between management and labor a larger than life impact. However, when two or three actors seated onstage are talking into the camera and their close-ups are projected on the rear wall, the hoped for cinema verité effect is overshadowed by a more powerful feeling that the dramatic flow is being interrupted for artificial artistry. The director is quoted as calling the videos “another character in the play,” but with a sophisticated audience, I think it takes away from their opportunity to visualize the import for themselves and stay in the moment.

David Chandler and Sally Wingert as Leo and Clara Gordon embody the central struggle of social responsibility versus self-interest, bending but not breaking under the ever-increasing burdens they must shoulder. Leo’s partner Sam Katz (Jonathan Epstein) and his wife Bertha (Adrianne Krstansky) show a tragic, dissimilar response to some of the same pressures. The three Gordon children, Ben (Hale Appleman), Julie T. Ryder Smith, and Pearl (Therese Plaehn), are ill-equipped to handle life’s disappointments and each finds an unsatisfactory way out. Gus Michaels (Thomas Derrah) and his daughter Libby (Merritt Janson) make their way in the world through the generosity of others. Only Kewpie (Karl Bury) and Mr. Pike, the furnace man (Michael Rudko), seem to be the masters of their own fate, seeing the world as it is, not as they wish it to be. Perhaps that accounts for their naturalistic, at ease portrayals of these secondary characters that represent the opposing consciences of the play.

Odets may not be as well known today as such contemporaries as Eugene O’Neill, Tennessee Williams, and Arthur Miller, but the 2006 Tony Award for Best Revival of a Play and the 2006 Drama Desk Award for Best Ensemble were won by his Awake and Sing! Nearly fifty years after his death in 1963, his message and vision still resonate and his voice deserves to be heard again. The A.R.T. is to be applauded for dusting off this drama, but the words ring truer on the page than on the Loeb stage.

Edge Boston, Kilian Melloy – Act One of the American Repertory Theater’s “America: Boom, Bust, and Baseball” series was the monumental Gatz, a reading of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby in its entirety. Act Two consists of Clifford Odets’ 1935 play Paradise Lost.

The play takes the name of Milton’s great poem with complete cognizance. Odets views the promise of America–democracy, opportunity, equality–as a paradise in the bud, perhaps not ever attainable, but so entrancing in its intimations of beauty and elevation that it remains worth striving for. Paradise is not a place, exactly, but rather an achievement, the goal being for all people to stand together in dignity and wisdom.

What stands in the way of this vision, of course, is human nature itself: the grimy self-service of politics, which betrays its own lofty rhetoric in the grind of its mundane gears; the uncertainty that can undermine talent and paralyze even young people in the prime of their vitality; the fundamental selfishness of a system that rewards the individual (maybe, if he’s lucky)–but at the cost of denying everybody else. By nature, we are adversarial, and so are our great institutions: the marketplace, government, even the family.

As an illustration of this, Odets takes us into the home of a large extended family, the Gordons, whom we meet as they are gathered around the table for dinner. Their house shows signs of construction: a renovation is underway, a fine metaphor for the market’s boom-and-bust cycle. In Act 2, the house will be finished, the furnishings new and shiny, and the family settled in, having arrived at some outward appearance of prosperity; in Act 3, the house will have been foreclosed on, and the furniture, we learn, is out on the street, where the family, too, is headed in short order.

But all of this takes a few years to unfold. Each of the three acts is a sketch drawn from a moment in time: an evening, an afternoon. The Gordon pere, Leo (David Chandler), designs handbags. His is the artistic vision, pure and idealistic, that is guided by aesthetic, and in turn informs his social attitudes. When he hears about his workers being overworked and cheated of their pay by his partner, Sam (Jonathan Epstein), Leo insists on improving their working conditions. It’s evident to everyone that this is not a wise move, business-wise, in the midst of a depression; even Leo’s wife Clara (Sally Wingert) declares that she’s married a fool, but she says it with loving forebearance. It is Leo’s idealism and his faith in humanity’s better nature that sustains her own optimism.

Sam may also think Leo is a fool, but it’s not an attitude that makes much room for admiration. Sam is a taskmaster and a hard-nosed businessman. He foresees disaster looming: times are tough, and the company simply cannot afford to be too generous. Sam is driven by fear, and by dissatisfaction; this turns into rage and casual cruelty, expressed in the insults he hurls at his meek wife Bertha (Adrianne Krstansky) and in his dismissive attitude toward the Gordon family’s friend Gus (Thomas Derrah)–“Do you have the five dollars you owe me?” is his customary greeting to Gus, delivered in a growl.

For his part, Gus is the father of Libby (Merritt Janson), who at the start of the play has just eloped with Ben (Hale Appleman), the son of Leo and Clara. Ben was once a star athlete, but his career has now been derailed by a weak heart–an all too apt diagnosis that could just as easily explain his fretful cowardice. When Ben’s shady friend Kewpie (Karl Bury) starts making advances on his wife, Ben hasn’t the stomach to do much about it. He doesn’t have the gumption to do much of anything: while Kewpie is making money hand over fist through his questionable activities and dressing in better and better suits, Ben is reduced to selling wind-up toys (Mickey Mouse: too perfect!) on the street corner.

In a juicy swipe at Wall Street, Ben’s banker brother, Julie (T. Ryder Smith) is afflicted with a “sleeping sickness” that has sapped him of his drive. Julie foresees chances to make money or avoid pitfalls, but his voice is never heard by decision makers: his is the sound business sense that is overridden by greed and economic adventurism, and he could embody today’s financial sector as easily as that of 1929.

With these characters in place, the structure of the play is ready for hearty polemic, but Odets adds a few more figures into the mix. Remo Airaldi makes a couple of appearances as Phil Foley, the hard-charging, utterly venal local politician; Theresa Plaehn portrays Pearl, Leo and Clara’s daughter, gifted as a musician but unlucky in love; Mr. Pike fetches up in each act to repair the furnace and to give voice to the sort of hard-left social consciousness that Leo may vaguely subscribe to, but seems to have little working familiarity with. (Pike is a brawler, easily the match for Foley’s malicious brand of politics; when Foley smears him with the label “red,” Pike snarls, “I’ll break your god damned neck,” his rage and forceful articulation a wonderful tonic.)

The production underscores the themes of the play in straightforward ways (the set design, as noted above), but also in a manner that Odets may have found amusing: by projecting video on the rear wall, director Daniel Fish has found a means to emphasize certain moments (a confrontation between Ben and Kewpie, for instance, or a scheme that Ben brings to Leo to recoup the money that the business is losing), and to set the play against a literal backdrop of human suffering, happiness, or profit-driven conspiracy.

But the use of projection serves also to cast a certain skeptical tone into the play’s central argument. The first scene shows the final moments and end credits of a movie; the family, at the dinner table, are caught up in it, like any contemporary family gazing at the television instead of engaging with one another in conversation. Seen as a bookend to the soaring speech that Leo makes at the play’s end–in the very pitch of extremis, his home and family tottering toward oblivion–this introduction asks us the crucial, if difficult question: are such high-flown visions of humanity’s grand future enlightenment mere illusion, as dazzling but as fake as any dream projected onto the silver screen? Have we made a faith out of our faith in our own better angels?

Scenic designer Andrew Lieberman seems to be in on the subtextual commentary. Though the play is set in the 1930s, Lieberman’s set mixes props and furniture from several subsequent decades: the 1960s through the 1980s. If the Gordons’ home represents America, and their extended family embody all of us, then the few years the play encompasses stand in for what looks right now like an 80-year-cycle of poverty, aspiration, prosperity, and collapse. The three decades that the designer evokes may have been the crux, the period during which we considered–and might have made–other choices, before, like Julie, we succumbed to a sort of political sleeping sickness, and apathy laid us out before economic predators like a human banquet.

The play is long, its style and pace from an earlier era, but its tone of outrage is contemporary. If Fish asks us to look at the question of hope–how real it is, how effective it might be in saving us from ourselves and each other–he also hits on another historical truth. The Great Depression had a couple of consolations to offer the struggling masses–one was bootleg booze, but the other was the movies. America hobbled, but Hollywood thrived, and we survived one of our most desperate national crises. Perhaps visions and dreams are enough to sustain us, after all.

Blast magazine.com, Jason Rabin – Daniel Fish’s staging of “Paradise Lost” swallows this powerful depression era drama by the great Clifford Odets into a yawning abyss of negative space, silence, postmodern distancing techniques, and pretentious theatrical effects. It is disappointingly reminiscent of the many pre-Paulus A.R.T. productions in which a rich script was delivered into the hands of brilliant actors, who were then painfully lead astray by a director determined to superimpose his own avant garde vision onto a classic, completely obscuring it rather than casting it in new light.

It’s clear why the play was chosen for this season. “Paradise Lost” was written by a poetic revolutionary during a time in which global economical disaster rippling from Wall Street was forcing Americans to question the very capitalist system that offered a cherished standard of living to the fortunate and a dream of an attainable-feeling glamour and comfort to those it had left out. Odets’ script explores the loss of the opportunities and dreams promised by a wealthier America. His tragic Gordon family plummets with the stock market, freezes up in denial trying to wait things out, and then finally, humbled, strives to come to terms with a new America whose playing field is level — but mired in tears and blood. It’s a powerful play, Odets’ most prideful effort, and one that he believed would bring audiences closer together and make them glad to be alive.

Fish, sadly, does not trust the script to speak for itself. Rather, he manufactures his own tone and set of symbols into which the play is caged. His production is neither set during the Great Depression nor in the present. References to the two periods battle one another as the audience searches for some sort of location. We’re given a set that is part family estate and part warehouse. A large kitchen table, the play’s central icon, sits in the middle of a vast and mostly bare stage, between a stack of wooden pallets to its far left and, to its right, an idealized statue of a man running, suggesting one of the play’s protagonists, Ben Gordon (the charismatic Hale Appleman), a former Olympic runner.

The Gordon family, their neighbors, and associates, spend the entire (nearly three hour) play (broken into three acts with intermissions) sitting at this table, apart from when they mill or sprawl around it. As they mumble to one another, they rarely face the audience and often avoid one another’s faces as well. Behind them hangs a gigantic screen onto which is projected some thematic television clips, some family movies seemingly set in an alternate production, some footage of talking heads from news programs over which character dialogue is sometimes (absurdly) dubbed, and some other bizarre and distracting effects that wretch the play away from its slightly poeticized realism into the realm of surrealistic collage.

If you drink some caffeine, crane your neck, squint your eyes, and ignore the strange meta-narratives, you might pick up the story of Leo (David Chandler) and Clara (Sally Wingert) Gordon, an upper middle class family struggling to hold together their family in light of the dying of their business. Their grown-up children are languishing. Their son Ben, the former runner, gets married, but with no money or prospects his new life is off to a sluggish start. Their younger son, Julie (T. Ryder Smith), who in other days may actually have been groomed as the family’s new patriarch, wilts into depression. Their daughter Pearl (Therese Plaehn) does nothing but obsessively practice the piano (or in this production, the anachronistic keyboard synthesizer with earphones to hide the instruments’ haunting effects) dreaming that she and her (absent) musician fiancé are just waiting for their big breaks. Also present are their doddering friend Gus Michaels (the great Thomas Derrah), a tragic clown, and their furnace man, a radical who lost his sons in the Great War and now looks only to ideology for comfort. This collection of grim fallen angels are poked and prodded, tempted and challenged by a series of friends and associates (most notably by Ben’s gangsterish buddy Kewpie played excellently by Karl Bury), until they must step out of their torpor and into the frightening new world.

These characters are well drawn and this production’s actors seem well cast. But it’s hard to tell. I spent most of this play trying to get my bearings and the remainder waiting for at least some sound and fury.

Far from in paradise, I mostly just found myself lost.

The Harvard Crimson, Ali L. Leskowitz – ART’s ‘Paradise’ feels more like Hell. If Bertolt Brecht and Steve Jobs collaborated on a play about economic downturn, the end result might look something like the lifeless, sluggish production of Clifford Odets’s “Paradise Lost” currently running at the American Repertory Theater (A.R.T.). Brecht would insist on calling attention to the show’s own theatricality, thereby distancing the audience and forcing them to separate their emotions from the action onstage in order to realize an important truth. Meanwhile, Jobs would persistently add more and more technology to the play, to no rational end. This is the feel of director Daniel Fish’s “Paradise Lost,” which runs through March 20: a muddled, pretentious mixture of inexplicable technology, estranging effects, and bizarre sermonizing that overshadows the fine actors and even the story itself.

Fish manages to remove any traces of life and energy from one of Odets’s best works, a tale about the survival of the human will in times of crisis. “Paradise” follows the Gordon family, who has lost their livelihood during economic decline. While originally set during the Great Depression, here the Gordons are re-envisioned as a contemporary family—one of Fish’s only directorial decisions that works, even if only in theory. Modernizing the Gordons and their neighbors would make their misfortune more relevant and immediate.

Yet any meaning Fish achieves with the present-day setting is negated by the baffling stark and technological aesthetic he forces on the show, which works against the script rather than with it. Videos projected onto a gigantic screen throughout the production are particularly off-putting. Even when the video works in a technical sense, it is distracting, unnecessary, and alienating. This is no fault of video designer Joshua Thorson, whose work is actually quite charming by itself. Rather, any video—even as engaging as Thorson’s—simply makes no sense here, where it takes away from the onstage action and detracts from the play’s narrative.

The use of video is particularly unfortunate when three factory workers visit patriarch Leo Gordon (David Chandler) and his business partner Sam Katz (Jonathan Epstein) to complain about their conditions. The unseen workers lodge their complaints, speaking into off-stage microphones while the screen plays clips of silently talking everymen. The effect is sloppy and confusing. If Fish is trying to equate the three workers with modern employees and their struggles, he certainly does not succeed; it is barely discernable what is actually even happening in the scene.

This disorder carries through with the needless use of live feed video. Many of the instances utilizing live feed seem to be the consequence of ill-conceived staging, such as the conversation between Ben (Hale Appleman) and Kewpie (a moving Karl Bury) in which both actors are seated on the floor with their backs turned to the audience, with large furniture further blocking them from view.

As a result of the projections, and several odd moments during which characters speak into handheld microphones, the production comes off as cold, sterile, and preachy. The cavernous quality of the Loeb Mainstage only adds to this empty feeling. While the various scenic elements—designed by Andrew Lieberman—are visually striking throughout the three set changes, their scattered placement on the vast stage also underscores the emotional barrenness of the production.

Actors almost never connect or collaborate as they recite lines; instead, they always seem to be yelling across the stage at one another from atop these purposely unfinished set pieces. Their placement makes them feel even more removed from the audience. Consequently, emotional peaks in the script fall flat. Fish certainly seems more focused on his concept than the story itself.

Despite the mess around them, most of the actors still manage to deliver solid performances. Sally Wingert is natural and funny as matriarch Clara Gordon. Thomas Derrah as Gus Michaels and Epstein as Sam are both powerful and fiery. T. Ryder Smith shines above all as Julie, the younger of the Gordon sons, and Mr. May, a corrupt businessman who tries to enlist Leo.

Smith’s one scene as crooked Mr. May is the only instance of a rewarding use of video in the play. Finally, the video’s detached feel makes thematic sense when projecting May’s image—in negative—as he speaks. His black-and-white face effectively reflects both Smith’s doubled role and May’s unfeeling nature.

Unfortunately, this is one of the only successful moments of the production, which ends on a fittingly impassive note for a show that stresses electrical connections over personal ones. Leo Gordon’s final speech about his hope for the future of mankind should be a stirring conclusion, but his delivery into a microphone instead turns it into a lecture. While the Gordons are left with nothing but their own faith in man’s work, Fish’s production leaves a far less reassuring impression. 03.09.2010

Boston Theatre Review, SMR – The American Repertory Theater’s spring festival, America: Boom, Bust and Baseball, presented it’s second offering at the Loeb Drama Center this week. Falling under the label “Bust”, Clifford Odet’s Paradise Lost is a pithy tale of loss in the wake of the Great Depression which has some startling, and at times disturbing similarities to our current economic climate.

I’m used to the A.R.T. offering cutting edge, rapturous opuses, going just a little bit farther than other playhouses in Boston to give the audience something more, but this production of Paradise Lost, directed by Daniel Fish, gave 3.5 long hours of dull dialog and confusing, shaky staging. It was hard to really focus on any one character or story because it felt like the author just dumped a bucket of story lines on the floor and left the director to try to piece it together lyrically in a way that makes sense, and that keeps the audience engaged.

Fifteen minutes into an extremely dense and nonsensical opening act, both of the people sitting to my right were fast asleep. They left after the first of two intermissions, along with about six other people around me. I can’t really say that I blamed them- I could barely keep my eyes open myself. I’m glad that I stuck it out though, because while the first act did drag considerably, the actors did help to liven up the story in the second and third acts, just barely keeping my attention.

There just wasn’t anything going on in the piece that I cared about. The characters were underdeveloped and there were far too many to keep track of, though they all seemed to live in the same house even though that fact was unclear and didn’t ever get around to being explained. As the story unraveled and we collected more tidbits about the characters and how they are related, I was less engaged and more annoyed that I had invested my mind into characters that I didn’t care about, respect, or understand. On the heels of the spectacularly character driven Gatz, Paradise Lost was especially disappointing.

Despite my obvious criticism of the play choice, and the lack of what I consider to be a firm directorial standpoint, the actors and actresses worked their hardest to give their character’s life, some succeeding better than others. I enjoyed the sharp tongue and good timing of Michael Rudko in his portrayal of Mr. Pike the furnace man, and T. Ryder Smith was very good as both the demonic Mr. May and younger son Julie (though it was sort of difficult for me to buy that he was the younger brother, he looks like he’s about twice the age of Hale Appleman who played his older brother, Ben). Ryder had the great instincts of a veteran performer which made him extremely interesting to watch, even after the character’s personal tragedies limited his range of motion in the third act. Sally Wingert also had some very nice moments as Clara, family matriarch. In fact, she best embodied the physical and emotional characteristics of the time period.

Another thing that I found both puzzling and ultimately distracting, was the choice to include modern clothing and technology into the show. While I understand that the audience was meant to see the parallel between the late 1930’s and today, I think we could have figured it out on our own without the Casio keyboard, the POD storage unit, and the Enron t-shirt.

I wanted a lot more from Paradise Lost than I got. The show did live up to its claim that it was a “bust”, though unfortunately I do not think it was in the way it was intended to.

Tufts Daily, Michelle Beehler – Risky ‘Paradise Lost’ incorporates blend of media. “Paradise Lost” portrays trials and tribulations of the Gordon family. In its current production of Clifford Odets’ “Paradise Lost,” the American Repertory Theater creates a new genre of entertainment that is a mixture of cinematic and theatrical media. Directed by Daniel Fish, the production toys with avant−garde techniques to gain at once a more detached and intimate perspective of one family’s dissolution during the Depression.

Despite having a plot that is steeped with traditional American themes and values, Fish’s interpretation is continuously experimental and risky in its attempt to reinvent and capture a glimpse of 1930s America. Before the show even starts, a western−style film is playing on the set’s gigantic movie screen. The dialogue starts just as the film is ending and the credits are rolling across the screen. The beginning of the show occurs at the end of something else, but like many elements of the play, it is a little unclear how the two connect.

The Gordon family is the center of the play. The show begins at the family’s kitchen table; it is also the place of arguments and the older son Ben’s (Hale Appleman) marriage announcement. Things quickly begin to fall apart as the characters are forced to leave the table and face responsibility, the failing economy and death. Problems escalate far beyond what the parents, Clara (Sally Wingert) and Leo (David Chandler), can handle. It’s not long before Clara’s easy answer to everything — to eat a piece of fruit — becomes trivial and nostalgic.

While the stage is always visually appealing, it also threatens to distract too much from the characters and plot. A gigantic movie screen acts as the backdrop and a window of intimacy as a camera follows the actors off stage and into corners obscured from the audience’s view. While the movie screen might allow for the actors to feel hidden and private, it also exposes them in gigantic terms at odd angles to outside viewers. The definition of theater is challenged here as technology is used to reveal the characters in new and different ways.

Microphones are another innovative adaptation to the production. Occasionally, a microphone is used for emphasis, such as when the younger Gordon son Julie (T. Ryder Smith) addresses his family and the audience as both an actor and a radio announcer. A microphone can also act as an element of feigned privacy when the characters are off stage and appear on the movie screen.

The blending of media from film to radio to theater is an interesting concept, but in “Paradise Lost,” the effect fails to stun and inspire. At times, it’s simply disjointing and distracting. But there are moments when the vision is almost there, such as the short movie that is played of Ben and Libby’s (Merritt Janson) wedding. The wedding video might succeed because it is separate from the play itself, filmed and put together previously, unlike the live film moments, which tend to be dark, awkward visuals of critical moments and conversations. But while the wedding video is excellent in itself, exposing moments of family tension and the first signs of Ben’s weakness, its incision in the performance is jarring and surreal. Questions remain about when the movie took place and whether or not it is imagined.

The acting in the performance is what holds the work together. It’s unfortunate that the set and tech sometimes get in the way of the performances. In his portrayal, Chandler captures the breaking of an idealistic man. Odets does not spare good and honest people — everyone is subject to tragedy. But even after so much loss and despair, Leo remains steadfast in grappling for a sense of fairness and morality in the world.

Smith is another standout in the performance. Experiencing a slow decay of a different sort — physically instead of idealistically — Julie is simultaneously the tearjerker and clown of the family. Smith, with his aimless wandering and quirky behavior, creates a Julie that is sometimes child−like in behavior, but infinitely wiser than many of the other characters in the show.

Boston Babblings blog, Matt S – There’s nothing wrong with ART’s production of Paradise Lost. It hits all the points it tries to hit, and very easily draws the intended parallels between the 1930s that Clifford Odets writes about and today. It’s also not particularly difficult to imagine a family today having struggles and setbacks of the Gordons; you hear about them in every human interest story on the nightly news, or any time a politician needs a story about “Main Street.” It’s all very believable, all very timely. And all that might even work against the production, because by the time the curtain falls for the final time, it just might not be that interesting to watch anymore.

The story revolves around the Gordon family: Leo (David Chandler), who runs a handbag manufacturing business with a business partner; his wife Clara (Sally Wingert), a driven matriarch who very clearly runs the family; their older son Ben (Hale Appleman), a former Olympic runner who hasn’t really found his place post-Olympics; their daughter Pearl (Therese Plaehn), a quiet piano prodigy; and their younger son Julie (T. Ryder Smith), a financial superstar who has become sickly for reasons unknown. Coming in and out of their lives are an assortment of neighborhood characters that are vague enough to be found anywhere, but specific enough that the audience can point to any of them and say, “I know that guy!” Through three acts we watch Leo’s business spiral, Julie’s health get worse, Ben deal with an uncertain future, and Clara fight to hold everyone together and survive as a family. It’s a pretty stereotypic post-Great Depression story that has gained new relevance in light of the world’s recent economic issues.

If I had to choose, I think I’d have to place blame on some design and directorial choices, and maybe on myself for believing too much hype about the director. Director Daniel Fish has a reputation for doing some crazy things, but I feel like that drive only made it about halfway through the production. The design is fairly abstract, and at face value pretty cool. One of the best elements is the use of video projected onto the backdrop behind the performers. Sometimes it’s used for atmospheric effect – the entire cast starts the show by watching the end of a movie together – but most of the time it’s used with live video to give the audience a different perspective on the stage action. That’s especially beneficial because a good deal of the action in Acts I and II take place significantly higher than the audience if you’re seated at floor level, as I was. It’s useful to get a better view of what’s going on off on stage left when the actors themselves are obscured by the dining room table. There’s a particularly good use in Act II as things start to fall apart for Leo Gordon and his business partner. Without spoiling anything, Leo’s partner introduces him to someone who can potentially “fix” their business in a particularly insidious way. The fixer is played by T. Ryder Smith, who also happens to play Leo’s son Julie, but there’s a nice negative filter used on the projected video that allows Smith to portray a much more treacherous nature that he had on his own as Julie, which furthered the distinction between the characters and added to the treacherous atmosphere of the scene.

Beyond that, though, a lot of the technical elements fell a little flat for me. At seemingly random times throughout the play, characters would pick up wireless microphones and use them for dialogue. There are some times when it was very helpful – again with the moments when you couldn’t quite see what was going on over near the wings or upstage – but many times they were used when actors were front and center, and their dialogue didn’t really strike me as needing to be accentuated in that way. It’s very possible I missed something, but it just didn’t work for me.

It also struck me as odd that Fish had all of these out of the box technical elements at work, but his staging itself was very straightforward. There are some seemingly clunky blocking decisions – characters staying onstage long after they should have left, and it isn’t clear if their physical presence places them in the scene, or if they are there representing something more abstract. Again, it just doesn’t quite mesh with the otherwise relatively straightforward staging. Again, there’s nothing wrong with traditional blocking combined with abstract design, but it seemed to me to draw more attention to what was out of place – the design – than it drew to the story being told. The story is very timely, so one would think you’d want the focus there. It almost seemed as if the ability of the story to draw relevant parallels was taken for granted, and so the creative focus moved elsewhere, but all it did was draw attention off the story and performances, which should have been the stars of the show.

And if you’re paying attention, there are some shining stars here. Clara Gordon, Leo’s wife, is brilliantly portrayed by Sally Wingert. Her performance is very engaging, but it’s also a credit to Odets as well; this is by all definition a modern woman in the 1930s script, something Wingert accentuates with a ferocity that no one else on stage can match. She’s got the independent, speak-her-mind attitude of a flapper out of the ‘20s mixed with an undying dedication to her family that truly convinces the audience that if anyone can keep a family together in light of all the crap thrown at the Gordons, it’s Clara.

Also of note is Karl Bury as Kewpie, Ben Gordon’s best friend who turns out to be not so good for him. Bury has a history on Showtime’s “Brotherhood” and HBO’s “The Sopranos,” both of which he channels for Kewpie’s small-time con personality. He strikes a good balance of clearly being terrible for Ben and this family, but also clearly caring about them. It’s a tough note to hit to put someone you claim as your best friend directly in harm’s way without degrading the friendship to nothing, but Bury does it well, and his guilt in the final act over what happens to Ben is a genuine as it is well-deserved.

Leo’s business partner Sam Katz (portrayed by Jonathan Epstein) and his wife Bertha (Adrianne Krstansky) also rise to distinction thanks to a particularly potent breakdown in the second act. It struck me through the first act that Sam was probably in the most “real” situation in the show, trying to keep Leo’s floundering business afloat, but once you hit the end of the second act you realize that Sam is on much more unstable footing than the Gordon family; the Katz family spiral is much more accelerated and precipitous than the Gordon family’s, and the Katz demise, while in less focus, has as strong an impact as the main story.

The rest of the cast is a little more muddled, though no one is out of place. I’m not sure if the issue lies in performance or writing. At various points throughout the play everyone is given their moment of focus, but there’s such an overwhelming malaise that hangs over the script that it takes a spectacular performance to break through that and be noticed.

The malaise is not misplaced – both the period of the setting and the modern time it alludes to deserve a melancholic attitude. And hope does fight through in the end – once again in the hands of Wingert’s Clara, who stubbornly (in a good way) INSISTS on maintaining her family’s pride, however damaged by tragedy and circumstance it might be. There’s no doubt why ART and Fish chose to preset Paradise Lost now in 2010, but some weakly-written characters and questionable design choices hold it back from being the poignant commentary it might otherwise be.

The Daily Free Press, Tiffany Ledner – Paradise Lost finds modern meaning. In a time when the ailing American Dream is paralyzed, with optimism as its life support, artists capitalize on our anxieties by featuring theater, film and visual art pieces that reflect the current standard of living, sometimes as a comedy with a cloyingly hopeful outcome. This approach, although demanded, desensitizes people, especially young adults who are flying their college coops to independently nest elsewhere. The showcase of “Paradise Lost” by Clifford Odets is a timely performance by the American Repertory Theater, exposing the impotency and weakness of Uncle Sam in a time when American citizens are scrambling for an outreached hand. The play acts as a mirror for the audience to place themselves in the characters of this Depression-era drama, but does so without the saccharine-laced optimism.

The director, Daniel Fish, takes a daringly expressionistic approach to the Odets masterpiece, his style complementing the controversial new A.R.T. Artistic Director Diane Paulus’s philosophy of turning the traditional theatre on its head.

Fish’s symbolism in expressing his descent of man is most obviously depicted with the death of Ben Gordon (Hale Appleman), the former Olympian-turned-social-recalcitrant to maintain his marriage and status. Gordon, who epitomized success, achievement and happiness, was not easy to tag antagonist or protagonist, as the desperation caused by the social and economic climate blurs lines of favoritism by the audience toward one character or the other.

The set design is centered on a projector screen that is used throughout the production, to cast the internal, hidden problems of American life onto all of us. Instead of trying to achieve a voyeuristic angle, the enlarged images facing the audience act more like an enormous mirror of contemporary life than a window into the past, also a nod to Odets’ idea of the “living newspaper.”

Fish’s expressionist vision is best portrayed with the casting of T. Ryder Smith as both Mr. May, the arsonist that offers his get-rich-quick services to Leo Gordon, and as Julie Gordon, the ailing son of the destitute family. With two pivotal characters being played by the same actor, Fish subtlety reminds the audience of the forces looming behind desperate decisions. Mr. May is projected on the giant backdrop in a haunting film negative, playing with our ideas of identifying what is positive and what isn’t, and the black-and-white direness of a family man’s desperation.

“Paradise Lost” is not meant to be a feel-good play that one skips away from clicking their heels singing the praises of the Sweet Land of Liberty. Instead, the artful and thoughtful combination of set deign, characterization and dialogue created by Odets but tweaked by Fish leaves the audience in a somber state of self-consciousness.

The Harvard Law Record, Jessica Corsi – More than Paradise lost in ART’s Depression-era drama.“For neither man nor angel can discern Hypocrisy, the only evil that walks Invisible, except to God alone….”

Unfortunately for theater goers attending the A.R.T.’s latest production, Clifford Odets does not appear to have taken this wisdom from Milton when writing his own Paradise Lost. The heavy-handedness of his writing flattens characters who are struggling through the challenges of the Great Depression and have no need of metaphor and abstraction. And while the A.R.T. has attempted to bring the drama to life with quasi-existentialism and innovative visual techniques, the story is deprived of true significance by its suffocatingly hollow dialogue.

Odets’ Paradise Lost is a tale of the well-intentioned, entrepreneurial Gordon family losing it all as they cling to each other, their dreams, and the right thing to do. Each family member and each character in the Gordons’ extended community is, however, little more than a caricature of an idea that Odets wished to emphasize, or a mere mouth piece for speeches on greed, equality, democracy, or the moral path. The patriarch of the family, Leo Gordon, is a soft dreamer, a philosopher turned business owner whose lofty ideals can’t keep pace with cut-throat capitalism. Mr. Gordon’s character is thrust upon the audience, frequently quoting radical, gentle philosophers. He is less grating than Pearl, the sole daughter of the family and a reclusive genius concert pianist who never achieved her potential. Mr. Pike, the furnace man living in the Gordons’ basement, is clearly the voice of Odets himself, tirelessly reminding the audience that the patriotic response to a financial crisis is the humane one, and that it is unnatural for humans to starve when the means to feed humanity have remained at hand throughout the economic downturn.

Pearl could have been the most interesting character but was relegated to a constant backseat, both by Odets’ writing and the director’s seclusion of her in the corner of the stage. The most profound social commentary in the play comes in her all too brief words on the individualism of American society. She has been abandoned by her fiancé as he seeks work in a bigger city and robbed of her chance to be the great concert pianist because this path was too expensive. Pearl declares that she is only worried about herself and her own well being. Here we see the tiniest glimmer of the explanation for where America was then, and where it is now. Odets wanted us to focus on the grand competing narratives of greed and profit, of politics and nationhood. What he left out is that most people can’t be bothered to think in those terms and instead mind only their own needs and those of their immediate family. If he could have melded the two forces—individual desperation and the indifference of an American government that has left individuals to fend for themselves—he could have painted a picture of the American character and culture and transcended his sometimes shrill, sometimes disconnected monologues.

It could have been the perfect time for the American Repertory Theater to revive a Depression era play about financial crisis and an American family struggling through foreclosure. But if the point was to connect modern audiences to the story of Depression era desperation—a narrative that needs little help to be evocative and meaningful in today’s bust cycle economy—the exercise failed.

The American Repertory Theatre placed a quote from Odets on its website: “It is my hope that when people see Paradise Lost they’re going to be glad that they’re alive. And I hope that after they see it, they’ll turn to strangers sitting next to them and say hello.” When the curtains closed on the final act, I was too despondent to want to talk. I was depressed by the subject matter, and by the fact that little has changed in almost 100 years of American prosperity—the boom is still too high, the bust is still too low. We feel the pain so sharply because of our system that allows us to grab it all without paying back into the community and which keeps corporate giants afloat while consumers founder. If our wealth went to the construction of strong social safety nets instead of to the insulation of individual’s pockets, we wouldn’t be in a foreclosure crisis right now.

But I was also sad for this missed opportunity of a play. Without a fully developed family of characters to rally behind, viewing Paradise Lost was about as touching as watching pundits debate on a 24 hour news channel. And if it’s one thing that is not going to move American culture or economics ahead, it is more one dimensional hot air dressed up as something worth listening to.

Suffolk University Journal, Tom Logan – ART play ‘Lost’ on crowd. When one thinks of Paradise Lost, the initial image that comes to mind is that of Milton’s epic poem about the fall of Satan and mankind’s exile from the Garden of Eden. Paradise Lost by Clifford Odets is a depression-era tragedy about a family that loses everything through no fault of their own. The play, directed by Daniel Fish, is being performed at the American Repertory Theatre until March 20.

Paradise Lost chronicles the life of the Gordon family, a middle-class American family living in the Great Depression, that slowly watches the life they worked hard to build come crumbling down. The head of the Gordon family is Leo Gordon (David Chandler), who struggles to do the right thing for his family and his business. His wife Clara (Sally Wingert) is a woman trying to keep her family together and support her husband. Ben (Hale Appleman), the Gordon family’s oldest son, is a bright-eyed youth that recently got married despite being unable to support his new wife. Julie (T. Ryder Smith), the youngest son, is a sickly young man that will soon die from an illness, and finally, the daughter, Pearl, (Therese Plaehn) is a young girl who loves to play piano.

Looking at the play, one really couldn’t tell that it even took place in the depression. All the characters wore modern clothes, there were images of modern cars, and the overall sense was that it tried to hard to seem modern as an allegory for today’s economic climate. This can be seen in some of the costumes that the characters wore. Julie wore an AIG t-shirt in the final act of the play. Another character, Gus Michaels, wore an Enron T-shirt. The problem with Fish trying to make the play more relatable to current events was that it fell flat on its face. Instead of putting on a play that was well-developed and had a message, Fish simply showed the audience the Great Depression and said, “See, it’s similar to today, isn’t it?”

The best word to describe this play would have to be preachy. The dialogue between characters didn’t sound natural, it seemed as if someone would bring up a topic, and then someone else would go on a ten-minute-long philosophical speech about their thoughts on it. For example, in the second act of the play, Clara randomly makes a statement about how if the United States is called to war, she will encourage her children to go fight if they are drafted. After that, Mr. Pike, the furnace man who apparently lost two sons in the first World War, went on a huge rant about how she’s wrong, all war is bad, and we’re evil if we encourage people to fight in them.

Another problem that this play has is that most of the story is more or less inferred rather than explained. For example, Mr. Pike never says that he lost both his sons, but it is heavily inferred that he did. Some of the major plot points in the play happen off screen, which takes away a lot of the action and leaves the audience with only words. It was similar to watching Hamlet, except without the scenes where the characters actually do something.

The biggest problem with this play would have to be the set design. It supposed to take place in the Gordon family’s home, but the set more or less looked like a warehouse. There was a scratched wood floor, a wooden round table, a stack of boards that were supposed to be stairs, and a long blue wall that looked like the outside of a house. There was also a couch that was placed offstage where few people could see it, a gold statue of Ben running that was never really utilized (or even acknowledged), and finally, a large movie projector screen in the background that was supposedly used to enhance some plot points.

The movie screen was probably the worst idea for many reasons. The long blue wall was in the way, and caused the images on the screen to look distorted. Some of the things shown on the screen were random and out of place. When the characters are talking about Ben, the screen suddenly showed a video of him running, which ultimately added nothing.

Also, the movies played on the movie screen were distracting. At one point in the play, Mr. Gordon is approached by a professional arsonist who offers to burn down his business so he can collect the insurance money. While he was making the offer, the movie screen projected a close-up negative image on the arsonist, which really distracted the audience from what the characters were talking about.

In the end, Paradise Lost tries to give a social commentary to today’s economy but ultimately fails. The only people that would possibly enjoy this play would have to be pretentious hipsters that want to sound intelligent at the next Starbucks pseudo-philosophical discussion. For everyone else, this is a play that is long, boring, and preachy. 03.16.2010

Arts Fuse blog, Bill Marx – Doing away with a “painted box set” does not necessarily free up our theater artists to provide compelling “visible and audible expression” of the cultural and political spirit of the present day.

In fact, given the depressing dependence on multimedia folderol in both The Book of Grace by Suzan-Lori Parks and director Daniel Fish’s tricked up production of Clifford Odets’s Paradise Lost at the American Repertory Theater (ART), the evidence runs in the opposite direction.

The addition of technology seems to ratchet up a compensatory dramatic hysteria, pumping up a production’s urge to float a bloated Important Message. The sweet modesty of Stick Fly’s comic meditation on race and class, presented in a non-videoized but well-designed set, comes as a funny, perceptive, and reassuring testament to the values of the provisional, on stage and off.

Current attempts to turn the stage into a giant TV screen seem to be part of an effort to reassure theatergoers that theater can be morphed into a new-fangled CGI movie (or into a disco party, The Donkey Show, or into an impressive arts installation, Sleep No More, earlier ART productions under the new “show ‘em its not just theater” leadership of Diane Paulus). The mania for the projected image wreaks havoc on the ART’s staging of Paradise Lost, an Odets epic that had a debilitating case of The Big Statement when it hit Broadway in 1935.

After the critical success of the one-act Waiting for Lefty, Odets was pushed to write more and more ambitious plays, but he lacks the talent for sustained dramatic construction—the lumpy, speechifying Paradise Lost earned Odets his first round of negative reviews, helping to send him away from the theater to Hollywood, where his talent for juicy dialogue and simmering visions of personal and public betrayal fit well (sometimes brilliantly, as in “Sweet Smell of Success”) into pre-fab movie formulas.

Paradise Lost is the de-evolutionary tale of a middle-class, American family, the Gordons. The Depression cleans out its bank account and eventually its home. On the way down, the Gordons grapple with the loss of life as well as with failed dreams of athletic success, artistic accomplishment, brotherly love, and financial security. Clara, the pragmatic wife, plays second banana to delusional merchant hubby Leo, who throughout the descent into poverty maintains his radical faith in the American Dream.

The script’s leftist politics generally serve as talky window dressing: when Odets confronts idealistic Leo with real world complications, such as how to provide better working conditions for the mistreated workers in his shop (we are asked to believe the old line that he didn’t know about the exploitation), the matter is dropped. But that is Odets’s scattershot approach throughout—even the major villain of the piece hasn’t the integrity of his own greed. Odets has him come on guilt-ridden at the end, offering the Gordons blood money just so the family, without a penny to its name, can honorably shame him.

Not content with that feel-good moment, the playwright struggles to provide a mega-inspirational final message: Leo’s oracular response to the nihilistic dressing down of a tramp Marxist. As amusing as it is to hear a ringing defense of Ralph Waldo Emerson (!) in the face of a communist lambasting, the mishmash suggests that the Gordons, despite Odets’s speeches to the contrary, remain out of touch with reality.

The playwright’s jump to Hollywood suggests that he saw the real value of escapism: critic George Jean Nathan opined that Leo delivers “such a lush panegyric to the future bliss of mankind as makes the ordinary happy ending of the commercial Broadway drama look like the finish of Othello.”

Still, Paradise Lost offers some of the crackling energy and slangy dialogue that makes even Odets in ersatz-Chekhovian mode fun to sit through. And the ART production will most likely be the only professional staging of the large cast Paradise Lost we will have the opportunity to see. But, obsessed with making sure the audience sees the “relevance” of the play, director Fish ladles on the giant video shots, TV commercials, hand-held mikes, and electric pianos. The result of the modern airbrushing is to make the play seem more, not less, dated. The abstract set is so barren that it defeats the message of the play: the Gordons have nothing to lose as they sink into terminal debt.

The performances feel underdone and earnest, the cast members making too little hay of the roller-coaster rhythms in Odets’s language, the kitschy patter of desires thwarted and dreams denied. The dramatist’s characters may be lost and broken, but their tongues are lively. T. Ryder Smith provides a standout turn as Mr. May, a professional arsonist who offers to set fire to Gordon’s shop for the insurance money—the performer offers a creepily conversational note of unrepentant evil, no preaching but a plain old invitation to despicable action. Jonathan Epstein offers some corrosive moments of capitalist self-hatred as the bedeviled Sam Katz, Leo’s tortured business partner.

Slow Muse blog, Deborah Barlow – What We can Be, and What We Are: Odet’s Paradise Lost. Watching the spectacle of a family coming unraveled has a long history. Greek dramas specialize in showing us the multi-generational demise of families, from the cursed House of Thebes in the Oedipus trilogy to the murderous implosion of the House of Atreus in “The Oresteia”. A particular strain of family dismantling drama deals with the dissolution of a family due to financial woes. The most famous example of that genre is Chekhov’s legendary “The Cherry Orchard”.

“Paradise Lost”, written by Clifford Odets 75 years ago, is an American Depression era take on the family-in-financial-freefall theme that played out with pre-revolutionary Russian poignancy in “The Cherry Orchard” 30 years earlier. But unlike Chekhov’s aristocratic milieu, “Paradise Lost” centers around an everyman, solidly middle-class family, the Gordons. Over a two year span we watch them as their world unravels, a process that is set into motion by the economic collapse of 1929. By the end of the play, the lives of their children have been irrevocably compromised, they have lost their home and what is left of their belongings has been thrown into the street.

For anyone viewing this play in 2010, the similarities between the Gordons of 1935 and the tent cities full of foreclosed American families are obvious and haunting. But to approach Odets’ play primarily as a prescient foreshadowing of our current economic and cultural woes is to miss much of its richness. Odets was an outspoken socialist who was enraged by the exploitative profiteering of the 30’s, and his political views are apparent in the play. But always rising to the surface in this story is Odets’ humanism: his characters struggle with how to live with honor, with a moral code and their integrity intact, especially when the most basic elements of survival are at stake. How differently Odets views his characters’ struggles when compared to other family-based contemporary dramas, like Arthur Miller’s “Death of a Salesman”, Eugene O’Neill’s “Long Day’s Journey into Night” or anything by Harold Pinter. The tone of the play is sympathetic, empathetic, nonjudgmental. And even with its starkly bleak ending, it is not without a redemptive note.

“I believe in the vast potentialities of mankind,” Odets wrote to the critic John Mason Brown. “But I see everywhere a wide disparity between what they can be and what they are. This is what I want to say in writing.”

The film director Krzysztof Kieślowski came to my mind while I was watching the performance. His approach to storytelling also speaks to an Odets-like humanism. In an interview published some time ago, Kieślowski said that he wanted to make films about real people and real life. People make really bad decisions he said, usually when they are still young, and then they spend the rest of their lives managing around those catastrophic mistakes. That’s what being human is about; we all suffer from our bad choices, our failures of judgment.

Odets’ play does not have the gentle benevolence of Kieślowski’s masterpiece trilogy, “Red”, “White” and “Blue”. But beneath the vitriol that Odets gives voice to in “Paradise Lost” is an undeniable alignment with what is human, even in the face of our glaring failures and shortcomings.

The production at American Repertory Theater, directed by Daniel Fish, is a brave and ambitious undertaking. Some scenes felt inspired and others didn’t quite come together. The set, a postmodern plywood assemblage with an arte povera feel, worked well as a foundation for all three acts. Video is incorporated, projected on the uneven surfaces at the back of the set which spoke to the dismantling we are witnessing in these character’s lives. The first act felt unwieldy and slow to engage (I went on opening night, so the blocking for that first act may still be evolving) but things tightened up considerably in acts two and three. As I have come to expect with most A.R.T. productions, the performances were all strong and well defined.

Just a note about American Repertory Theater: Diane Paulus began her artistic directorship of the A.R.T.in Cambridge this year, and it has been the most memorable season in my 25+ years as a subscriber.

Boston Phoenix, Carolyn Clay – After Eden. Clifford Odets’s 1935 Paradise Lost, which is getting a rare revival from the American Repertory Theater (at the Loeb Drama Center through March 20), also treats issues of class — though at more of a poetic roil than a cheeky simmer. And in the wake of the all-new Diane-Paulus-helmed ART’s recent Shakespearean sorties to Studio 54 (The Donkey Show) and Manderley (Sleep No More), Daniel Fish’s period-hopping, video-augmented approach to the Depression-era drama, stretched across the wide Loeb stage, is a little like a resurgence of the Taliban after “Mission Accomplished” on the aircraft carrier — a return to the old ART, except that the previous regime would never have laid its auteurist hand on anything as homegrown and eloquently propagandistic as Odets. That said, Fish’s visually enhanced production — its huge screen both dwarfing the performers and offering their travails in close-up — ameliorates without upstaging Odets’s somewhat speechifying, quaintly slang-ridden vision of a humbling yet humanizing revolution in which a once-prosperous middle-class family, the shards of its dismantled (or perhaps never mantled) life thrust out on the street, lose everything except the possible dawning of a new day when “no man fights alone.”

Of course, it doesn’t take genius (or the AIG T-shirt that appears in the third act) to see the keen contemporary relevance of Odets’s 75-year-old portrait of mid-level haves brought low by massive unemployment, an imploding economy, and what original Paradise Lost director Harold Clurman dubs in his introduction to the printed script the “general fraud” perpetrated by the upper classes. Here, idealistic handbag manufacturer Leo Gordon is brought to ruin (and hope) by the conjoined machinations of the Depression, his own honest dealings, and ambush by an unhappy, unscrupulous business partner. Going down with Leo is a large cast of characters representative of a decaying, deluded middle class; they include his immediate family (their dreams of opportunity and accomplishment dashed), various hangers-on who as much as live with the Gordons, and one socialist-manifesto-spewing furnace stoker. Only the hustling, criminal character of Kewpie (originally played by Elia Kazan) thrives — rich but empty.