Excerpts from the reviews

Full reviews are below

“Puppets, satire, war, fairy tales and the Crucifixion are a start for ‘Passion’. Though utterly accessible, Sarah Ruhl’s “Passion Play: a cycle in three parts” is such a monumental attempt to synthesize the religious, social, historical and theatrical worlds of the past two millennia that you might well stagger out of the theater and into the real world in a slightly vertiginous state. . . . The whole thing is at once wondrous, transfixing and vaguely hallucinatory . . . ” Hedy Weiss, Chicago Sun-Times

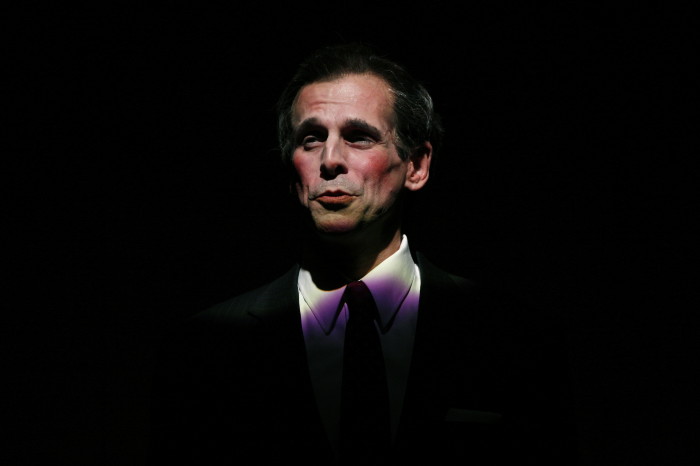

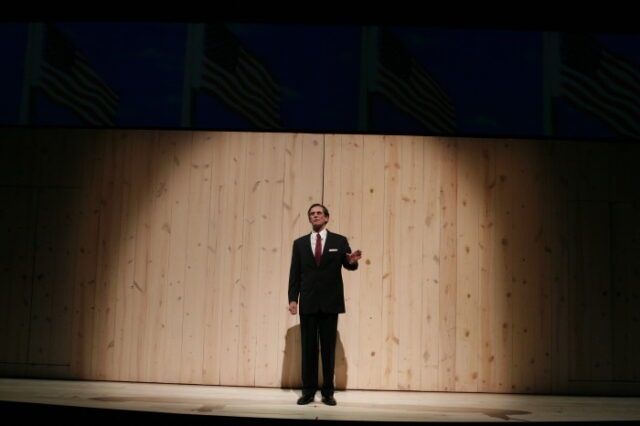

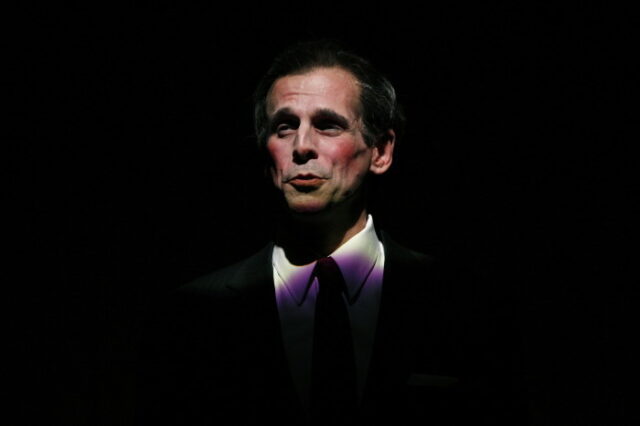

“Passion Play actually dares to try and blow up the complex, incendiary co-existence of the secular and the sacred in Western culture. If you weary of triviality and repetition in the theatre, this is your show. It almost makes your head explode . . . A trio of colorful authority figures are all played with great flourish by T. Ryder Smith. And his Hitler makes the audience shake in their boots.” Chris Jones, Chicago Tribune

“Glorius dramatic poetry, beautifully staged. At once, simple, whimsical. and profound . . . It’s beauty and thoughtfulness overwhelm all quibbles. . . Each act portrays the leader of the day, with Queen Elizabeth 1, Adolph Hitler, and Ronald Reagan making appearances, and all played with a nimble mix of style and conviction by T. Ryder Smith.” Steve Oxman, Variety

“Brilliant . . . To experience this kaleidoscopic work is to come away dazzled — by insights, by imagery, by the clever mixture of the comic and the profound, and by the sheer scope of the production. To experience it is also to come away bemused, puzzled by ideas and conventions that are not easily understood: deliberate and provocative enigmas. . . . Special kudos to T. Ryder Smith for his Elizabeth/Hitler/Reagan.” Beverly Friend, Chicago News-Star

“Using several dramatic tools of her generation—unchecked whimsy, ironically misplaced historical figures, antitheatrical technology—Ruhl’s play somehow manages to suggest perversion, despotism and gigantic floating fish without dramatizing any of it onstage . . . Wing-Davey’s production can’t make heads or tails of the script’s detached imagery, but the director is certainly adept at handling actors with eccentric gifts: spectacular stage creature T. Ryder Smith leaves mouths agape as Queen Bess, Der Führer and the Gipper . . . As a play, it’s merely an overwrought misfire. As an event that professes to speak to the moment, it’s a charade.” Christopher Piatt, TimeOut Chicago

Publicity

Offstage

Above, top: my dressing table. I applied and took off elaborate makeup 9 times per show, including having to take two quick showers.

Below: Jenee Garretson, my sweet, sassy, fiercely organized and absolutely tireless dresser.

Full reviews

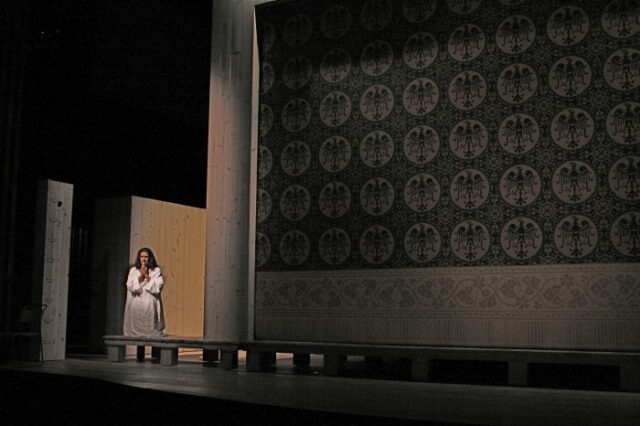

Chicago Sun-Times, Hedy Weiss – 2,000-year pageant dazzles, charms. Puppets, satire, war, fairy tales and the Crucifixion are a start for ‘Passion’. Though utterly accessible, Sarah Ruhl’s “Passion Play: a cycle in three parts” is such a monumental attempt to synthesize the religious, social, historical and theatrical worlds of the past two millennia that you might well stagger out of the theater and into the real world in a slightly vertiginous state. To be sure, Ruhl’s work, which opened Sunday at the Goodman Theatre, is no academic exercise. The Wilmette-bred writer (author of “The Clean House” and winner of a MacArthur “genius” fellowship), is all for play, and the play of ideas. And with the collaboration of Mark Wing-Davey, an endlessly inventive, highly detail-oriented director — as well as a slew of ingenious designers, and a cast that morphs seamlessly through three acts spanning four centuries and an operatic-style running time of 3? hours — she gives us poetry, fairy tales, soap opera, puppets, satire, literal and figurative flights of fancy, and three different takes on the religious pageant about the crucifixion of Christ denoted in the play’s title. Along the way there are “guest appearances” by Queen Elizabeth I, Adolf Hitler and Ronald Reagan. There are troubling pregnancies and acts of adultery. There are war and warring brothers. There are anti-Semitism and anti-Catholicism. There are miraculous fishes. There is a village idiot who sees everything and sometimes becomes the sacrificial lamb. There are obstreperous theater directors and actors just being actors. There are riffs on tourism. There are the show business of politics and the politics of show business. And beneath all the greasepaint there is a scrubbed-bare reality that suggests the greatest passion plays of all are those played out in our daily lives, and in the intersection of those lives with the greater forces of history. Theater has it charms, but reality is where the true drama lurks. The whole thing is at once wondrous, transfixing and vaguely hallucinatory (think Gabriel Garcia Marquez meets Mary Zimmerman). It also can be overly precious. Only so much ingeniousness can be absorbed, no matter how many charming surprises, whimsical riffs or darkly ominous dreams unspool. In each of the show’s hourlong plays, the lives of a group of amateur actors, and the lives of the biblical characters they portray, are at odds. In a sense, the running joke here is that everyone is miscast — whether in medieval, plague-ridden England, at the Nazi-ridden 1934 Oberammergau festival in Bavaria, Germany (the strongest scenario), or in the vast expanses of South Dakota during the Vietnam War and later Reagan years. The leading actors — the exceptional Brian Sgambati, as well as Joaquin Torres, Kristen Bush, Nicole Wiesner, Polly Noonan, T. Ryder Smith, Craig Spidle, Brendan Averett, Keith Kupferer and John Hoogenakker — form an airtight ensemble. And Allen Moyer’s highly adaptable, movable feast of a set (gorgeously lit by James F. Ingalls, with remarkable projections by Ruppert Bohle and a splendid soundscape by Cecil Averett) add magic to this mystery tour. 9.25.07

Chicago Tribune, Chris Jones – “All my life, I’ve wanted to play Christ,’ says a spunky Elizabethan actor at the top of “Passion Play,” Sarah Ruhl’s audaciously expansive Goodman Theatre deconstruction of the long and oft-inglorious history of depicting the Son of God on the stage. You can’t blame the fellow. Jesus was the lead role in the passion plays of northern England. Fringe benefits — popularity, gorgeous women, temporary sainthood — accrued to the lucky actor, while the poor sap playing Pontius Pilate got the cold shoulder. The Prince of Peace also snared top billing in Oberammergau in 1934, even under an Austrian director who was a member of the Nazi party. And in South Dakota some 50 years later, Jesus on your resume was the best ticket out to Hollywood. In contrast to the role, though, the actors were always imperfectly human. Indeed, the entire biblical narrative has proved dangerously malleable in the historical petri dish of the theater. Explored in Ruhl’s whimsical, quirky, post-modern style, but with a scope and thematic heft wholly atypical for this gifted, Chicago-bred writer, those fascinating ironies and hypocrisies lie at the core of the flagship production of the Goodman season. This is not a show for the exhausted. It almost makes your head explode. “Passion Play” runs in excess of 3 hours, and it feels as if Ruhl would have preferred still more time. It features myriad styles and a chronological span of more than 500 years. Mixing fiction and real life in the epic-theater tradition of “Angels in America,” it includes appearances by Elizabeth I, Adolf Hitler and Ronald Reagan. And despite a concept that you first think is going to be two planks and a passion, Mark Wing-Davey’s colossal and exuberantly staged production eventually reveals eye-popping (and occasionally gratuitous) quantities of scenery and self-referential special effects, including a full-on ascension into the heavens. Produced only once before at Washington’s Arena Stage and revised for its Chicago premiere (which has a new director), “Passion Play” actually dares to try and blow up the complex, incendiary co-existence of the secular and the sacred in Western culture. If you weary of triviality and repetition in the theater, this is your show. Indeed, “Passion Play” could be a great Anglo-American theatrical epic in the tradition of “Angels” or “The Coast of Utopia,’ for it homes in on the great, central struggle of our moment. “Angels” declared sex a political act; “Passion Play” wants to do the same for art. But Ruhl, a great American writer, has yet to wrestle her massive canvas into manageable cohesion.

Simply put, whenever this show fully commits to the truth of the three worlds it conjures — 16th Century England, 1930s Austria and 20th Century South Dakota — things work superbly. Thanks to a clutch of fine multicharacter performances from Joaquin Torres, who plays Jesus three times, and Kristen Bush, who keeps wrestling with the Virgin Mary, we become deeply involved with the life and times of these earnest actors. And we see the connection between the triumvirate of colorful authority figures (all played with great flourish by T. Ryder Smith) and those who toil and play in their shadow. But this show keeps wanting to subvert its own rules. Actors switch without warning to archetype (the Achilles’ heel of Wing-Davey’s otherwise thoroughly exciting production). And then the theatrical world they’ve so carefully built suddenly goes haywire. That sense of esoteric but highly intelligent whimsy that serves Ruhl so well in her smaller, more defined plays sometimes trips her up here. The otherwise charming and moving first part, for example, ultimately gets overwhelmed by the appearance of several giant fish on the stage. Granted, they’re part of an important dream metaphor (even if they reminded me of Tony Soprano), but they still undermine the truth of the moment and pull you out. In current form, the section of the show set in Oberammergau is by far the strongest and clearest. Aside from Smith’s Hitler making the audience shake in its boots, Ruhl catalogs everything from anti-Semitism to British appeasement to the collapse of a simple villager unable to cope with being too old to play Jesus. But whereas Hitler says things you don’t expect, Ruhl’s Reagan is a familiar stereotype. And as that easy joke prefigures, things go awry in the middle of the final segment, set, confusingly, in both the late 1960s and the 1980s, and mostly following an actor (played by Brian Sgambati) just back from Vietnam. The play veers off in too many esoteric directions, losing its focus. And the production goes with it. Allen Moyer’s otherwise cohesive design palette scatters into video, a huge cut-out ship and God knows what else, and Wing-Davey’s direction loses its anchor. From the seats Sunday night, it was like this great, involving, unified, thrilling opus had finally slipped from your fingers after three hours of keeping it mostly in your grasp. You won’t be able to sleep for worrying about the loss, which is reason enough to see this show while you’re awake. 9-25-07

Chicago Free Press/Curtain Up, Lawrence Bommer – The specific “Passion” in Sarah Ruhl’s three-act triptych is of course a presentation of the last days of Jesus Christ, as enacted in three local pageants across four centuries. Showing how life mocks art, the same character types revert to kind—a village idiot, an unfaithful girl playing Mary, closeted lesbian lovers in England and male ones in Germany and bombastic authority figures (respectively, Queen Elizabeth, Hitler and Reagan). The contrast between their sacred roles and real lives is exploited for dramatic effect. (For instance, traumatized by war, the 1969 Pontius Pilate refuses to wash his hands of the blood of an innocent victim.)

Parallel situations or events (preparation for war, rehearsal chaos, a procession of larger-than-life fishes, a scary red sky) bedevil these troubled “Passions.” They’re played out in a British hamlet in 1575 (where “Passion” plays are feared as dangerous holdovers from the former Catholic faith), Oberammergau, Germany, circa 1934 (where the play’s anti-Semitism perfectly complements Nazi propaganda), and Spearfish, South Dakota, between 1969 and 1984 (where backstage shenanigans almost erupt in a “crime of passion” play). Ruhl (whose “Clean House” also liked to stir things up) tackles many truths here—the unholy marriage of politics and religion, the disconnect between mortals’ make-believe and their real motivations and the self-fulfilling power of a play to alter everyone connected with it. But the overlong, cluttered and scattershot plot, directionless dialogue, quixotic symbol-mongering, knee-jerk magic realism, self-indulgent side scenes and aimless, lazy apostrophes to the audience take a cumulative toll. The third act self-destructs as it lurches off in a dozen inconclusive directions. Worst of all, we never get a sense of what the “Passion” play really means to its participants, the benchmark from which we can measure their assorted departures from the dream. Instead we get a toxic fusion of the condescension of “Waiting for Guffman” with the calculated irreverence of “Springtime for Hitler,” always minus the fun. Actor/teacher Mark Wing-Davey knows his way through the dramatic labyrinths of this sprawling and unfocused trilogy but not so well that an audience can’t go missing in (the) action. How does Hitler’s anti-Semitism fit Queen Elizabeth’s anti-Papist rant, then fit Ronald Reagan’s genial Know-Nothingism? It’s safer to dwell on such acting epiphanies as Joaquin Torres’ questing Jesus, Kristen Bush’s very merry Mary, Polly Noonan’s “fool of God” village idiot and T. Ryder Smith’s tour de force as the play-acting political icons of their era. These performances, necessarily rich diversions from a squandered script, get us through the 220 minutes without suspending too much disbelief. If only there were real passion in “Passion Play.”

Chicagocritic.com, Tom Wiliams – Overly ambitious, unsettling Passion Play trilogy unfolds as a most thought provoking epic. After spending over three and a half hours with Sarah Ruhl’s Passion Play, a cycle in three parts (at the Goodman Theatre), I was so overwhelmed that I had to take a long walk on the beach that night to sort out all the high drama, passion and ideas contained in this epic. Seldom have I been as ambivalent about a play as I am about this one. There is so much happening in Passion Play that I could justify writing a most negative review, yet I could also find so much to admire and appreciate that I could justify raving about the play. My feelings about this show run deep. For sure, Passion Play is a recommended show—one that serious theatre patrons need to witness even at the risk of not liking it. So let me be clear here—the sheer theatrics and the ambitious effort to commingle politics, religion and morality into a compelling story (however flawed) and theatrical event renders Passion Play worth seeing. That said, I must tell you about the achievements and flaws in this most original spectacle. Sarah Ruhl’s structured Passion Play in three part—1575 Elizabethan England’s Passion Play; the Oberammergau Passion Play in Bavaria 1934 and the Passion Play in Spearfish, South Dakota in 1969. This allows for Ruhl to trace the connection between the actors (many of which are amateur local citizens), their religion and politics of each era. Many of the players take on the persona of Jesus, Mary and Pontius Pilot, etc. in their daily lives hinting that mixing theatre, religion and social morality over lap immensely. Ruhl marvelously weaves those elements in a spectacular saga filled with humor, raw sensuality and fervor. In Act One, set in 1575 England, I was perplexed at the use of Irish brogues that seemed to vary in accuracy. I also found the frontal nude scene where the carpenter disrobes in front to the audience to be gratuitous. Act one sets the tone of complex and, at times, uneven presentations of multiple themes. We see the villagers as zealots living out their beliefs through the Passion Play. Director Mark Wing-Davey keeps the complicated show flowing. The “village idiot” (Polly Noonan in a terrific comic turn) underscores and gives voice to non-actors and outcasts in the village. The symbolism of John the fisherman is exemplified by a larger-than-life fish parade dream sequence. The appearance of Queen Elizabeth I fuels her anti-Catholic witch hunt. The conflicts of those with strong religious beliefs are acutely dramatized here. Act Two, set in 1934 Bavaria, Germany just as Hitler completes his dominance of Germany, allows Ruhl to picture the basic German anti-Semitism as the Oberammergau Passion Play unfolds. We see a German officer (John Hoogenakker) trying to seduce the lady playing Mary (Kristen Bush). He also discovers that Eric (Joaquin Torres) and the Footsoldier (Brian Sagambati) are gay lovers. We see that the Passion Play has patriotic meanings as well as a vehicle of discrimination and hatred. The interwoven conflict of morality and the state are emphasized in Act Two. Act Three finds the Passion Play being done in rural South Dakota in 1969 during the Viet Nam war. Here Ruhl tackles anti-war themes with a confusing entry of Ronal Reagan attending the Passion Play while running for re-election. Problem: the act is set in 1969 and Reagan was President from 1981-89 and he ran for re-election in 1984. I’m not sure why Ruhl uses Reagan here since it isn’t clear when the play jumps to 1984, if it does? By the way, T. Ryder Smith was terrific as Queen Elizabeth, Hitler and Reagan. Sarah Ruhl denies that she was trying to equate the three world leaders. Act three blends adultery, personal mutilation and anti-war themes with a caricature of modern American Presidents as more actors than statesman. I think the following quote from playwright Sarah Ruhl is apt: “I feel that the play is kaleidoscopic, so it should have something for people on any end of the ideological spectrum.” I believe that Passion Play is about the relationship between politics and theater and religion and theater. Perhaps, Ruhl paints too broad a picture and tries to cover too many themes and she tries to tell too many stories, perhaps? I appreciate the sheer effort that mostly works. After all, theatre should always stretch to reach new heights. Ruhl establishes her vision deftly. Kudos to her chuptzah. Allen Moyer’s movable wooden set on James F. Ingalls’ fine lighting design with Ruppert Bohle’s projections gave the play an eerie epic look. Nicole Wiesner and Kristen Bush gave excellent performances as the ‘Mary’s’ while Polly Noonan was brilliant as the Village Idiot and Violet. Joaquin Torres and Brian Sgambati anchored the show with smart, emotionally wrenching performances. Come see this provocative saga to see the fresh voice of the talented Sarah Ruhl on stage. Not all of the three hours works as designed, but there is enough meat to stimulate animated after show discussions. Originality dominates in Passion Play.

Chicago Newsstar.com, Beverly Friend – A kaleidoscope of images and ideas. The very best works of literature and art open a frontier, breaking new ground, presenting original images or the juxtaposition of older images in new and innovative ways. This is true of the works of such greats as James Joyce, T.S. Eliot, and Picasso. It is also true of the work of Sarah Ruhl in her brilliant “Passion Play: A Cycle in Three Parts.” To experience this kaleidoscopic work is to come away dazzled — by insights, by imagery, by the clever mixture of the comic and the profound, and by the sheer scope of the production. To experience it is also to come away bemused, puzzled by ideas and conventions that are not easily understood: deliberate and provocative enigmas. The core of the three and a half hour production lies in three versions of the dramatization of the last days of Christ: first in medieval, 1575 England, then at Oberammergau in 1934 Germany, and finally in 1969 (and later 1984) in Spearfish, South Dakota. Far more than an illustration of historic drama, the focus is on actors who assume the essential roles and insights into the influence of these roles on their lives. Need the actress playing the Virgin Mary actually be a virgin? What is the impact of a Christ who is drawn to the Nazi party? What can and should actors bring to and take away from their depictions? There are not just three stories here; there are at least six, as we are watching plays embedded within plays. Each Biblical betrayal is matched by a contemporary one. Throughout, the citizens playing Pontius Pilate (Brian Sgambati) and Jesus (Joaquin Torres) struggle as they continually shift between good and evil within a complex relationship of religion and politics. Unlikely characters weave in and out: Queen Elizabeth, Hitler, and Ronald Reagan freely move from their own time periods into each others. A village idiot (Polly Noonan) adds texture and conscience, much like the character of the fool in a Shakespeare production. Ruhl has been quoted as saying, “It was like those Russian nesting dolls, I kept uncovering new thoughts and ideas.” These include war, the role of rulers, taking responsibility, and far more as she delineates her ideas with a unique mixture of allegory, mythology, and history. Under the expert direction of Mark Wing-Davey, 16 fine actors take on multiple parts, with special kudos to T. Ryder Smith who plays Queen Elizabeth, Hitler and Reagan, and to Sgambati and Torres, circling each other as they vie for the actress who plays the Virgin Mary (Kristen Bush). Kudos to Allen Moyer for amazing set design which makes excellent use of moveable stark, wooden walls, set against sequences of filmed sky, forest, and war scenes. This play, stunning as it is, will not be to everyone’s taste. At the press preview, about five percent of the audience departed after the First Act and about an equal number after the Second. It is their loss, but to be fair, this is a difficult play, brimming with complex material that takes time to digest. Much is never explained, so it satisfies emotions while bemusing the intellect. Ruhl, a Chicago-area native who was a recent winner of a MacArthur Foundation Fellowship and a 2005 Pulitzer Prize finalist, is without doubt playwright worth watching. 9.26.07

Centerstage, Rosalind Cummings-Yeates – The most successful theater productions provoke thought as well as entertain. Using those criteria, The Goodman’s “Passion Play: A Cycle in Three Parts” is stunningly successful. It takes the medieval tradition of passion plays, which re-trace the last days and resurrection of Jesus, and manages to make the events relevant, humorous and engaging. However, on other levels (such as accessibility and a well-paced story), the 3 1/2– hour-long drama falls short. For a generation whose attention span rarely extends beyond the quick hits of IMs and blogs, “Passion Play” presents a long-winded challenge. Playwright and Wilmette native Sarah Ruhl proves that her MacArthur “genius” fellowship was well-earned with an inventive tale that connects characters in 16th-century England, 1930s Germany and ’60s and ’80s South Dakota. A fascinating examination of how actors are affected by their holy roles, the play illuminates how politics influences religion. Recurring characters include a hot-boy Jesus who’s chased like a rock star and lusted after when his loincloth falls (and provides eye candy in a gratuitous full frontal nude scene), a Mary who hates to sleep alone and who’s “never been with child but doesn’t know why” and a Mary Magdalene that never seems to get any. Polly Noonan’s Village Idiot stands out with childish honesty and wise observations. All the players recreate versions of their roles in each act, traversing Elizabethan times, Hitler’s Germany and Reagan-era America. The second act, set in Oberammergau, Germany (only 75 miles from Dachau and brimming with anti-Semitic undertones) works the best and boasts the most focused, emotional writing. Appearances by Queen Elizabeth, Hitler and Reagan help set a surreal tone, as each demonstrates how religion can be twisted to fit ideology. However, the play veers too much into whimsy at times (life-size fish appear in every act and are quite tedious by the last), making it hard to swallow in one night. 10.2.07

Chicago Reader, Albert Williams. Play and Replay. Many people—believers and nonbelievers alike—view Jesus and Satan as the opposite poles of our moral compass: pure good and pure evil. But in Passion Play: A Cycle in Three Parts, dramatist Sarah Ruhl focuses on Pontius Pilate as Christ’s mirror image. The son of God died to take the sins of humanity on his shoulders; the Roman governor of Judea, according to gospel, refused to accept responsibility for the Messiah’s crucifixion even though he ordered it, literally washing his hands of the guilt. In Ruhl’s inventive but uneven work, the face-off between Pilate and Jesus is replayed in the context of a passion play—or rather three of them. Ruhl’s three-and-a-half-hour drama, whose three acts are set in different historical periods, spins variations on an emotional triangle between the actors portraying Jesus, Pilate, and the Virgin Mary in liturgical dramas reenacting the crucifixion and resurrection. As the trio’s relationships change in each scenario, so does what these iconic figures represent. The dramas are set against the politics of the times in which the characters live—turbulent eras when leaders exploited religion to embody moral as well as temporal authority. The show’s first—and decidedly most successful—portion takes place in an English village in 1575, when the country was reeling from the anti-Protestant purges of the late queen, Bloody Mary. Her sister and successor, Elizabeth I, has restored Protestantism as the state religion, but closet Catholics cling to their annual passion play. “The stage is our house of worship,” declares John, the intense young fisherman who’s been cast as Jesus. John’s cousin—conveniently named Pontius—covets the part of Christ but must settle for the role of Pilate. Pontius is in love with Mary, the pretty lass cast as the Virgin Mother, though she has an eye for John, who looks damn good in a loincloth. But John’s faith has bound him to a life of celibacy. When Mary gets pregnant by Pontius and her role is taken over by an eccentric teenage girl dismissed by others as the “village idiot,” John must grapple with the limits of his power to help the woman he chastely loves. And when Queen Elizabeth arrives to assert her symbolic role as virgin mother to England—and to sternly reinforce the primacy of her religion—the town faces the prospect that its passion play will be canceled. The second act is set in 1934 in the Bavarian town of Oberammergau, where the passion play has become an international tourist attraction—and a showcase for anti-Semitic propaganda. The woman playing Mary is the mistress of a Nazi officer, the actor playing Pilate is a soldier, and Eric, the youth playing Christ, is his lover. Like his Elizabethan counterpart John, Eric burns with the need to believe in something; he finds it in Hitler, who comes to Oberammergau to give his blessing to the production. But Eric’s commitment to the Fuhrer’s plans for rebuilding Germany comes with a price: he must betray an innocent Jewish girl—played by the same actor who was the Village Idiot in act one—who’s blurted out a prophetic warning of the Holocaust. Act Two anticipates war; Act Three examines war’s aftermath. It’s 1984 and Ronald Reagan, running for reelection, has arrived in Spearfish, South Dakota, where an Up With People-style passion play makes a perfect campaign stop for a president whose base of support is the fundamentalist Christian right. The problem is that Spearfish is still recovering from the wounds of Vietnam. Here the actors playing Jesus and Pilate, called simply J and P, are brothers. P served in Vietnam while J went to college and studied acting. P is married to Mary, but J fathered Mary’s daughter—who may be the reincarnation of the Jewish child from Oberammergau. Suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder, P is haunted by visions, including visitations from Hitler and Queen Elizabeth. Like Tony Kushner in his AIDS epic Angels in America, Ruhl melds reality and fantasy, refusing to clarify whether these visions are hallucinations or acts of divine intervention. But as the fantastical aspect grows more dominant in the third act, the play loses focus. The closer Passion Play gets to our time, the farther removed it feels. The characters and conflicts in act one are credible and moving; the story’s simplicity reveals its deep moral dimensions. Act two turns preachy as Ruhl focuses on the evil of Nazism; the male lovers’ furtive relationship seems a contrivance, and Mary veers dangerously close to campy caricature, suggesting the villainess of a World War II melodrama. She also gets the show’s worst line, delivered in response to her Nazi boyfriend’s complaint about being stuck home alone with the furniture: “Lamp shades don’t make for very good company.” By act three, Passion Play flounders, taxing an already tiring audience’s patience with an avalanche of visual imagery, including a procession of oversize fishes and a huge 16th-century sailing vessel that appears out of nowhere and carries Pilate to heaven. The ship may be intended as a final coup de theatre, but it comes off as a desperate, self-indulgent gimmick to bring the evening to a close. Ruhl and director Mark Wing-Davey are clearly paying homage to the spectacle of the traditional passion play. But they unintentionally strip P’s emotional and spiritual crisis of all reality and trivialize the tragic impact of the Vietnam war. And it’s odd that there’s no reference to how the Reagan revolution empowered the Christian right. First seen in 2005 at Arena Stage in Washington, D.C., Passion Play is being significantly reworked during its run at the Goodman. Wing-Davey has assembled a first-rate design team, but the elaborate production, with its flying boats and zooming media backgrounds, often overshadows rather than complements Ruhl’s crisp, confident language. But Wing-Davey shines in directing the fine cast. Ruhl’s decision to have the same actors play parallel characters in all three acts could seem gimmicky but doesn’t because of the depth and gravity that Joaquin Torres as John, Brian Sgambati as Pontius, Kristen Bush as Mary, and Polly Noonan as the village idiot bring to their roles. Their emotional honesty is a strong contrast to T. Ryder Smith’s intentionally heightened artificiality as Elizabeth, Hitler, and Reagan. Juxtaposing the stories of simple people with the interventions of iconic historical figures is a bold concept, and if Ruhl can tighten this sprawling, overlong work, it has the potential to excite as well as illuminate. 9.28.07

Daily Herald, Barbara Vitello – Time Well Spent. When does 3½ hours not feel like 3½ hours? When one spends them immersed in Goodman Theatre’s remarkable production of Sarah Ruhl’s “Passion Play: a cycle in three parts,” a strikingly original work filled with beguiling images and sustained by big ideas expressed with a light heart rather than a heavy hand. A fanciful examination of religion, politics and theater, “Passion” — with its clever construction, multiple layers and poetic writing characterized by gossamer lines like “she is like air breathing in the body of a violin” — is a must-see show. Much of the credit goes to Ruhl, a Wilmette native and Piven Theatre alum, whose “Passion” both celebrates and satirizes theater. A running joke involves a tweedy Englishman, who informs German natives he’s writing a book on theater, to which they respond, “Really? A whole book?” But the success of Goodman’s production also rests with Mark Wing-Davey for his bold, imaginative staging and fluid direction and with an always engaging, immensely talented ensemble.The play centers around three performances of the passion (a theatrical depiction of the last days of Christ) taking place in 16th-century England, 1930s Germany and late 1970s to mid-’80s America. Each act consists of a performance of the pageant. Throughout the play, the same actors portray Jesus. Pontius Pilate, Mary and Mary Magdalene as well as their offstage counterparts — ordinary men and women often bewildered and overwhelmed by the roles they play.Ruhl and Wing-Davey have crafted an epic, a whimsical, surreal spectacle whose artfully conceived visuals include giant fish gliding across the stage while the fisher of men casts his net against a blood-red sky; a Technicolor Ascension straight out of the 1970s and an exquisitely enigmatic maritime image that leaves one speechless. But “Passion Play” is not all splashy visuals. There’s the wonderfully intimate farewell between lovers as one goes off to war; a cringe-inducing moment where a young Jewish girl is shut up in a cage; a deliciously lowbrow scene set in the Garden of Eden — all less grandiose, but no less affecting. The overarching theme is the manipulation of religion for political purposes by charismatic leaders, represented by Elizabeth I, Adolph Hitler and Ronald Reagan (wonderful cameos by T. Ryder Smith), who exploit theatrical conventions. But it also considers love and betrayal, intolerance, faith and religion, identity, and the extent to which we conform to the role fate or society assigns us. Yet this “Passion” is intensely personal, revealing the human drama behind the religious performance. As arresting as it is (thanks to brilliant work by designers Allen Moyer, James F. Ingalls, Cecil Averett and Ruppert Bohle), “Passion Play” engages us most powerfully when it does what all great drama does: Tells one individual’s story. In the whimsical first act, it’s the illicit affair between Mary and the fish-cutter playing Pilate. In the gripping but unsettling second act (the best of the three), set in Oberammergau in 1934, it’s the story of the outsider (a touching performance by the consistently excellent Polly Noonan), the city’s lone Jew and the reluctant Christus (a charismatic Joaquín Torres). And in the sometimes confounding third act (which suffers from shifting time periods and wavering focus) set in the post-Vietnam War era in Spearfish, S.D., it’s the traumatized Vietnam vet who has lost his faith (the terrific Brian Sgambati). Time is valuable, and 3½ hours is quite an investment. “Passion Play” is worth it. 9.28.07

Gay Chicago magazine/Chicago Stage Review, Venus Zarris – I received a letter a few days ago wherein a dear friend and brilliant theologian wrote, “Church and state are strange bedfellows, but they are married till death do them part.” He could not have imagined the prophetic impact of reading his words only days before seeing this treatise on that very proclamation. Passion Play: A Cycle In Three Parts is a prime example of theater’s ability to exonerate us from the banal indulgences of our ever-growing collective superficiality. Playwright Sarah Ruhl produces more moments of genuinely awe inspiring communal dramatic wonder in Passion Play than I have ever experienced in any church. If you have been waiting around since “Angels In America Parts 1 & 2″ for a theatrical marathon that resurrects your cerebral perceptions and emotional investments, this is the dramatic rapture you are looking for. Ruhl reincarnates sixteen characters and our collective consciousness through three different time periods and locations of war in history. The framework is the medieval tradition of the Passion Play and the characters are the actors in it. Part One takes place in England, 1575, as Queen Elizabeth is banishing Catholic rites thereby forcing the play to cease production. Part Two takes place in Germany, 1934, where the Passion Play proves a powerful propaganda vehicle for Hitler’s anti-Semitic agenda. Part Three travels forward in time to Spearfish, South Dakota where art imitates life.We have more than enough of politicians, producers and celebrities. In this theatrical age of revivals and regurgitations, what the world needs is writers; thinkers who have the ability to not only observe and duplicate but to distill and deviate the human experience on visceral and existential levels inducing illuminations that connect this transcendence to the ground by way of humor, drama and passion. Ruhl facilitates this collective experience of tribal catharsis and epiphany on a level that is subversively powerful yet beguilingly entertaining. In our current time of war, the brutal chaos of our reality facilitates a necessity for time travel to provide context if we are to ever rise above the madness. Sadly, this has yet to be achieved but the astronomical journey that Ruhl takes us on is a profound step in the right direction as we explore with her the personal and contemporary questions of sexuality, identity, responsibility, faith, power, citizenship and war. Normally, if someone yells fire in a theater you should get out. But Ruhl’s amazing script, Mark Wing-Davey’s astonishing direction and the brilliant kaleidoscope perfect ensemble has set the Goodman Theater on fire and it is a blaze that you should toss yourself on. If you see no other play in the 2007/2008 season, see playwright Sarah Ruhl’s hilarious, haunting and at times horrifying Passion Play: A Cycle In Three Parts. The profundity and scope of the writing is matched by the excellence of the Goodman Theatre’s production thereby constructing a convergence of creation that represents theater’s potential to engage us in ways that not only entertain and enlighten but effect a change in the individual conscience that can subsequently impact the collective one. You can cross your fingers and hope that a brilliant director has the vision and influence to get this produced for cable TV, which sadly may never happen, or you can take advantage of the once in a lifetime opportunity that you have right under your nose and see THIS production, live, on stage as it is meant to be experienced.

Joyfully Perplexed blog, Alicia Victoria Joan Torres – Passion Play–Mary vs. Christ. “Passion Play, a cycle in three parts” by Sarah Ruhl. Amazing. Never have I been impressed by a piece of live theater before as I was with this young writer’s socio-historical-theological critique on the human condition through the means of passion play presentations–in Elizabethan England, Nazi Germany and Vietnam Era South Dakota. My friend and I had a chance to see the show on Wednesday of preview week. It officially opened September 24th at the Goodman Theater in Chicago, and will run through October 21st. Check out the Goodman Theater’s Website for tickets and other such information. Miss Ruhl spent over 10 years writing and researching this play, and her efforts shine through. True, there are kinks to work out, but the realism combined with the absolutely fantastic should earn a ticket to Broadway one day. I could spend several days talking about the various layers of the play, but perhaps one theme to consider first is the character of the Virgin Mary. Virginity is a topic debated, discussed and often despised. In Elizabethan England, we have a Mary who is crazy for sex, and fantasises about the Christ character in a sexual manner. This is rather interesting from an artistic/Theological perspective. In many Renaissance period pieces of art where the Virgin Mother is depicted holding the Christ Child, the Child touches the face of the Virgn–which is a symbol of sexual love. It essentially witnessed to a spousal relationship. The relationship of Christ and his mother was spousal in a certain sense–in that they complimented one another. There was no human sexual relationship involved, yet, in a Spiritual sense, there was a spousal witness from Christ and His mother. This is clearly twisted by the Mary figure in the first act of the play…which ends in tragedy. In the second act, the Oberammergau woman who plays the Virgin in their theatricals is also a virgin…and virginity seems to be highly revered–yet, revealed is the fact that virginity can be nuanced in definition. There is really no relationship between the Mary and Christ character in this act, which plays out in an interesting way–the Christ figure ends up having no interest in being Christ… Finally, in the last act of the play, the Mary figure actually gets married to the Pilate character…yet, there are issues brought on by Vietnam…and marital infidelity on the part of ‘Mary’ with the ‘Christ’ figure…once again, the disordered relationship of ‘Mary’ and ‘Christ’ ends in tragedy…

One could argue, based on an analysis of the Virgin Mary character in the play, the importance, theologically, of Mary’s relationship to Christ. In none of the three acts, in none of the three periods in history, was the Passion Play actually produced to completion. I would argue that this is because the Virgin character and the Christ character never display an ordered relationship. There is so much more to be said about this play. The themes run deep and are intricate, but serve to provide much material for reflection and dialog. I look forward to exploring more of the issues brought to light by this play, and hope that you take the opportunity to see this play for yourself! 9.23.07

Marissabadilla.com, Marissa Badilla – Chicago’s reputation as a theater town made it imperative for me to see a show when I visited last week. I’d first thought I’d look somewhere other than the big regional theatre, the Goodman–maybe Steppenwolf or Lookingglass? But, ironically, Steppenwolf was doing The Crucible, that regional-theatre staple…and the Goodman was doing the big, new, exciting show: Passion Play: a cycle by Chicago native Sarah Ruhl. According to Ruhl’s playbill essay, she “started writing this play ten years ago after rereading a childhood book which includes an account of Oberammergau in the early 1900s.” I’m pretty sure I know what book she means–Betsy and the Great World, part of the classic Betsy-Tacy series by Maud Hart Lovelace–because it made an impression on me, too. When Betsy goes to see the famous German passion play, everyone in the book knows exactly what “Oberammergau” signifies, and treats the play as a great and holy effort–meanwhile, I’d never heard of it, and I was shocked to learn that the actor who played Jesus would willingly be crucified, onstage, for fifteen minutes! Ruhl saw potential in this for writing a play that would explore religion and politics, art and life; big subjects, which she handles adroitly. The “cycle” has three acts, each set in a different time and place: Elizabethan England, where the Queen is cracking down on Catholic rituals like passion plays; 1934 Oberammergau, when the Nazis have just seized power; and South Dakota during the Vietnam War and its aftermath. The play is a backstage drama (like many theatre folk, I’ve got a soft spot for this genre) where in three different eras, three different sets of relationships are affected by current events and by the play that all the characters are working to perform. This multilayered set-up provides a real challenge for actors. For instance, the same actress (Kristen Bush) plays the Virgin Mary, as well as the woman portraying the Virgin Mary in the passion play, in all three acts. But her relationships to the other characters shift from act to act. In a sense, then, she’s playing six different roles–two in each act, onstage and offstage! However, all of the actors at the Goodman were very good: I especially liked how Brian Sgambello (Pilate) and Joaquín Torres (Jesus) slightly altered their physicalities from act to act. Also, because the anti-hero is usually more interesting than the straightforward hero, Passion Play’s sympathies lie with the Pilates of this world, not the Jesuses. If that sounded confusing, don’t worry: this concept is much more complicated to explain than to watch. At the Goodman, the play was smoothly directed by Mark Wing-Davey: the set seemed plain at first but interesting elements popped out of it as needed, and the large cast (11 speaking actors plus 5 silent supernumeraries) moved as a fluid ensemble. The Elizabethan first act of Passion Play is terrific–funny, intelligent, moving, with characters that you care about and Ruhl’s trademark poetic dialogue. In fact, I’d even call it a perfect 55-minute play. And those are hard to write: I can think of perfect 15-minute plays and perfect 2-hour plays, but not another perfect hourlong play. In 55 minutes, this act covers a lot of ground, and ends before the themes become redundant. The second segment of the play (Nazi Germany) is much weaker, and that’s a pity, because it probably has the richest material to explore. Should it have been a full-length instead? Here, the actor who plays Pilate is a German soldier, and the actor who plays Jesus is his lover. Provocative stuff, but I don’t think Ruhl made palpable the experience of being a gay man in Hitler’s army, or even a gay man in the ’30s. The study guide mentions that the “Night of the Long Knives”–when Hitler purged the Nazi ranks of all “threats,” including homosexuals like Ernst Röhm–occurred in 1934, but this important information is not worked into the play. Another storyline, in which the actress playing the Virgin Mary gets hit on by a Nazi officer, doesn’t go anywhere. If it’s an attempted comment on the role of women in the Third Reich, much more could have been done with this theme. Thankfully, Act 3 is a lot better. Spanning several years in the 1970s and 1980s, it feels like a bit of a departure for Sarah Ruhl: more contemporary and with plainer dialogue than she usually writes. (The Clean House is ostensibly contemporary, but set in a “metaphysical Connecticut.” Passion Play creates an all-too-real South Dakota.) Usually Ruhl’s dialogue gets noted for its lyricism and quirky turns of phrase, but when that gets stripped away, as in the South Dakota scenes, you realize that she is a very strong dramatic writer. For instance, I loved an exchange where one character accuses another of belittling him by saying “actually” all the time–it got me to see things differently, since now I’m hyper-aware of when I say “actually”! And I’m glad to discover for myself that there’s more to Sarah Ruhl than her vivid and whimsical imagination–she’s got a damn solid technique too. A minor irritant: in a scene set in 1984, a character we know is 14 years old (we know she was born in 1970) says she’s in “sixth grade”–but most kids are 11 or 12 in sixth grade. She even talks rather babyishly for an 11-year-old. Would it have been that hard for the girl to say, instead, that she was in “eighth grade” and have slightly more mature dialogue? A bigger problem: Though, as I said, Passion Play is less whimsical than other Ruhl plays (no one turns into an almond or dies of laughter here), at the end she brings out the old whimsy. I can tell it’s supposed to be lyrical, spectacular, and literally “uplifting,” but it just seems to come out of nowhere. The earlier parts of the script do not seem to lead to this conclusion, and it feels like a pasted-on happy ending. Actually.

New City Chicago, Fabrizio O. Almeida – Lucky for Goodman Theatre audiences, playwright Sarah Ruhl does not believe in the separation between church and stage. Her “Passion Play: A Cycle in Three Parts” is the second major new play opening this month to deal head on with the thorny issue of religion, and it’s easily the best. Unfurling over three superbly crafted acts, Ruhl’s fiercely imaginative work depicts the staging of the Passion of Christ—his trial, death and resurrection—by three different sets of people at three turbulent points in history: sixteenth-century England; a Bavarian town in 1934 Germany; and South Dakota, United States, circa 1969. Ruhl’s concern is with what happens when ordinary individuals telling an extraordinary story dangerously lose sight of fact from fiction. As well, she poses the question of whether the telling of this story over time has ultimately hurt or helped us. In hindsight, act one is the play’s cleverest because it lays the groundwork of dialogue, verbal motifs and character connections that will come full circle when echoes and semi-reprisals of them will appear in the later acts. The religious imagery (red skies, multiplying fish) may be a bit heavy-handed here, but it makes for some stunning stage pictures, especially against the clean lines of Allen Moyer’s relaxed, multi-functional unit set. The second act, the play’s emotional core, features a chilling cameo by Adolf Hitler and best illustrates Ruhl’s anger with the hypocrisy of world leaders who manipulate Christianity to promote a very un-Christian agenda. The final act, making heavy use of magical realism and replete with cameos by Queen Elizabeth, Hitler (again), Ronald Reagan and a procession of giant fish (!), sees Ruhl’s play become less focused, unwieldy and almost crack under the strain of its own ambition. But by this point it matters little. The searing theatricality of director Mark Wing-Davey’s nimbly paced production has kicked you in the gut while Ruhl’s writing and characters have etched themselves in the brain. “I don’t know whether this country needs more religion or less religion,” a character says at the end of “Passion Play.” Even after three and a half hours, I don’t know either. I only know that this is the play that everyone will be talking about and rightly so.

NWI.com, Philip Potempa – Have faith. Sarah Ruhl’s ‘Passion Play’ trilogy a creative powerhouse on Goodman’s stage. I’ve seen many interpretations and adaptations of the story of Christ as told in the “Passion Play.” And ever since the age of 13, when I first became a reader at my church, I’ve even annually read the words of Pontius Pilate (and all the other male voice parts) during our church’s services each year on Palm Sunday and Good Friday. Still, given all of this, nothing could prepare me for what I would see last weekend on stage at the Goodman Theatre in Chicago at the press opening of “Passion Play: a cycle in three parts” written by Chicagoland Pulitzer Prize-nominated playwright Sarah Ruhl. This clever, funny, thought-provoking masterpiece challenges audiences to think about many things during the course of the production’s three and half hours (which seems to breeze by with two short intermissions). I hinted in Sunday’s column that I would be seeing this play and that it even included castmember Polly Noonan, who can be seen in a brief, yet memorable role in the 1986 film “Ferris Bueller’s Day Off” and who has family here in Michigan City. Noonan, the only castmember appearing in Chicago who actually originated her role as “the village idiot” in play’s earlier unveiling elsewhere, takes control of every scene she’s featured in during the first two acts, with her distinct voice and an honest, bright and energetic portrayal of a young girl with insight into the inner spirit. Most importantly to emphasize, this is a play about three very different and yet very similar stagings of the “Passion Play.” The same cast of 16 characters play all of the roles in all three acts, which span versions of the “Passion” being staged first from the days of the Renaissance in a small town in England around 1575 (at a time when the Queen has just been excommunicated by the Pope and she has abolished such art forms) and then fast forward to the famous German village of Oberammergau around the time of 1934, as the Nazi party is coming into power. Lastly, in what is the weakest of the three acts, the scene is Spearfish, S.D., at the time of the Vietnam War and the “Passion Play” is more important than ever before for new reasons. During the course of the play, there are adult themes, a flash of nudity and some minor harsh language. There are also cameo appearances by famous faces like Queen Elizabeth I, Adolph Hitler and President Ronald Reagan. Most of all, these are characters surrounded by a clever and very functional set design, that the audience not only connects to, but also cares about as a new old story unfolds. 10.3.07

The Phoenix, Loyola University newspaper, Dan Platt – Playwright Sarah Ruhl takes a crucifixion cruise. Ambition is key for telling a story that spans 300 years, features speeches from Queen Elizabeth and Adolf Hitler and at one point submerges the stage in a sea of man-sized fish. It takes talent, however, to do it well. The Goodman Theatre’s Passion Play: a cycle in three parts is one of the most innovative and exciting, if intellectually insurmountable, productions to hit Chicago in years. Pulitzer Prize-nominated playwright Sarah Ruhl’s latest opus chronicles the staging of the Passion at three politically turbulent historical junctures: Elizabethan England, 1934 Germany and Cold War America. Each cycle focuses on a rural community culturally sustained by the annual crucifixion production. Ruhl’s play examines how this strange tradition affects relationships and identity, as well as how the exceptional political climates impact the Passion and vice versa. And it does so masterfully. The most striking aspect of Passion Play is the acting, for which the entire cast merits praise. Particularly, T. Ryder Smith as the Queen, Hitler and Ronald Reagan delicately blends humor with powerful political magnetism, revealing the amiability between acting and ruling, which is key to Ruhl’s story. His gestures and inflections convincingly capture the gravitas of sovereignty. Polly Noonan also deserves much recognition for her balanced portrayal of the village idiot, a character whose uncorrupted sincerity juxtaposes the rampant inauthenticity of the townspeople. She embodies a childlike innocence while gracefully avoiding childlike annoyance. The production’s use of props is also rewarding. From the group of whimsical-yet-provocative fish to the puppet-like convoy of sailboats blown all over the stage by the breath of actor Brian Sgambati’s third-cycle Vietnam veteran, the fantasy of Passion Play is refreshing. The Goodman seems to recognize that theater doesn’t have to be about despondent characters pouring over hyper-signified commonplace objects; sometimes symbolism can be loud and fun. Artistic director Robert Falls and projection designer Ruppert Bohle should be credited with beautifully blurring the division between the imaginary and the real, an ambiguity that furthers the production’s thematic goals. Stylistically, this production is in a class of its own, unique and invigorating, a real treat to witness. The only part of Passion Play that stands out as deficient is the final soliloquy, delivered by Sgambati’s recovering veteran. Delivered in the company of stagehands hard at work disassembling the set, the speech seems framed as an epilogue, promising some guidance or contextualization for the entertaining yet overwhelming three hours of content. However, no such closure is offered, with both text and acting conveying a light-hearted, softening attitude instead of a clarifying one. The disappointment of these final 10 minutes shouldn’t be ignored but neither should the difficulty of capping off such an emotionally and intellectually massive theatrical event. Passion Play should be applauded for many reasons: In the spirit of monumental projects like Tony Kuchner’s Angels in America, Sarah Ruhl’s latest work uses its size to address big issues without becoming clumsy and irrelevant. Furthermore, it can truly be called a collaborative effort; it is really no more Ruhl’s success as it is the Goodman’s, the director’s, the actors’ or the set designer’s. This production works because so many people are doing their jobs so well. It’s a revitalizing shot in the arm for Chicago theater and a play that everyone, aficionados and greenhorns alike, are sure to be delighted. 10.3.07

Seeing The Form blog – Last night I had the good fortune to be taken to the theatre by a stunning benefactress. After a quick mimosa, we were drawn into a web of politics, religion, and theatricality in Sarah Ruhl’s three-play cycle, entitled simply, Passion Play. Currently in production at the Goodman, Passion Play portrays three communities and their passion plays: the first in 1575 northern England; the second in 1934 Oberammergau, Germany; the third beginning in 1969 South Dakota. All three are set on the backdrop of political upheaval. All three locations have a tradition of passion plays (the passion play of Spearfish, South Dakota was begun by a displaced German actor in the 1940s), and all three are set in times of conflict. The passion play, for those without knowledge of theatre history, has its origins well into ancient ecclesiastical rites, but became especially popular during the Middle Ages. With plague and upheaval everywhere, the guilded (though not often gilded) productions of passion plays were a popular source of hope and the acclamation of a community’s faith in the midst of desperate times. One could almost call the production of a passion play in a community a kind of lay rite, a ritual of theatre that empowered ordinary people to do something holy. It is in this context that we follow the key characters in their portrayals of biblical characters (especially prominent are Mary, Pontius Pilate, and Jesus) and in their more “real” lives. Although the setting of producing a passion play is a constant, the political backdrop of each is unique. Queen Elizabeth’s reform of England was in full-swing in 1575; 1934, naturally, is located in the foothills of Hitler’s Nazi regime and WWII; and in 1969, there was no part of America not affected by the Vietnam conflict. Three influential and theatrical leaders rise up and claim the stage at crucial moments in each movement. Queen Elizabeth, whose reform of England was the cause of much spilt Roman Catholic blood, figures prominently throughout the cycle. Hitler naturally appears in one movement and makes a small appearance in another. And Ronald Reagan, who eventually inherited the veterans of Vietnam, charms his way into the final piece of the cycle. All three political heads had a flair for theatricality: Elizabeth with her makeup and royal pomp; Hitler, who utilized acting and theatricality to enhance the effectiveness of his speeches; and Reagan the former and charismatic actor. The cycle is humorous and haunting, tender and tragic, comedic and carnivalesque. Of course Ruhl investigates questions of faith and doubt, of politics and repression and enlightenment. But perhaps the most important question we are initiated into in her cycle is the question she puts in her notes to the cycle. After describing the aforementioned theatrical leaders, Ruhl asks, “But what is the difference between acting as performance and acting as moral action? It is no accident that we refer to theaters of war.” Or consider the words Reagan says at one point (loosely quoted), “I think people are afraid of actors. They’re afraid we’re good at lying. But really we’re just extraordinarily good at telling the truth.” Again from her notes: “Never have the medieval world and the digital age seemed so oddly conjoined. I’m interested in how leaders use, mis-use and legislate religion for their own political aims, and how leaders turn themselves into theatrical icons.” Although she could use a staff (historical) theologian, Ruhl’s cycle is magnificent. Every once in a while a bit of the dilettante in matters religious comes through (I speak as a trained theologian, what can one expect). Even so, the cycle is brilliant in its examination of the intersection of theatricality (performativity?), politics, and religion. A work of art of the highest caliber.

As an added bonus, however, Emily was wise enough to realize the playwright was sitting next to me through the first two movements (only moving to the empty row one down from us for the third). Upon discovering that it was she, the production stage manager, and director (Mark Wing-Davey), I was naturally very pleased to have handed her her waterbottle at one point, which she had forgotten in her previous seat. But in truth it was such a wonderful opportunity to peripherally be informed by their reactions as well. Upon leaving I made a point to thank the director (the playwright was otherwise engrossed in her laptop) for the beautiful event, which I think caught him a bit off guard since he responded with a bemused, “Well…yes…thank you…you’re welcome.” So it is with great pleasure that I recommend to you all Passion Play: A Cycle in Three Parts by Sarah Ruhl. P.S. Should any of you be in the Chicago area to see it at the Goodman, please be advised that the parts of Village Idiot/Village Idiot/Violet, played by Polly Noonan; Pontius the fish gutter/Footsoldier/P, played by Brian Sgambati; and Queen Elizabeth/Hitler/Reagan, played by T. Ryder Smith, are exceptionally wonderfully played.

Theatreworld.com, Ruth Smerling – What is holy, what is mundane? Sarah Ruhl’s PASSION PLAY, A CYCLE IN THREE PARTS, is a complex, haunting and stirring work. There actually three plays in one, each depicting a moment in history in a unique location, were a group of actors get together to put on the annual Passion Play, reenacting the crucifixion of Jesus Christ. The first play is set in 1575 England. Even though the play is outlawed and Catholic priests will be hanged, a devout group of actors keep the tradition alive. They are busy recreating the holy event, but egos get in the way. One actor envies his cousin who is always picked to play Jesus. Two women muse about their sex lives during a break and the angelic-looking actress chosen to play the Virgin is soon pregnant. The next play moves to Ober Ammergau, a beautiful town in Bavaria occupied by the Nazis. As the play goes on, Hitler makes an appearance. Now the Passion Play is no longer just a Christian tradition, it has become a Christian tradition in a society whose very philosophy is shattered to bits and replaced by radical tyrannical thinking bent on destruction. The final play in the cycle ends up in the Badlands of South Dakota where a famous Passion Play still runs every year to this day, where Ronald Reagan gives an opening speech. PASSION PLAY, directed by the acclaimed and celebrated Mark Wing-Davey, works much like performance art, a very visceral experience that wells up slowly into an epiphany. The imagery in the play is often surreal and must be interpreted on a personal level, much like religion and each person’s relationship with God. What PASSION PLAY does drive home loud and clear is that the people who continue to proliferate what is considered holy, valuable, important do their jobs only to serve entirely selfish agendas. The extremists are represented of course by Hitler, Queen Elizabeth makes an appearance in the first play, warning people that to act is not their job, it is the job of the sovereign to maintain what is to be believed in. Her majesty , played by T. Ryder Smith, makes an appearance in each cycle. A superb cast includes Brendan Averett, Kristen Bush, Alan Cox, John Hoogenakker and Keith Kupferer. Peggy Noonan is the Village Idiot in one cycle and Violet in another, a character not in the Passion, on the sidelines, mentally challenged and disruptive who garners interest from both the audience and the director played by Craig Spidle. Brian Sgambati, though never allowed to be crucified, is truly the one bearing the cross in the work, always haunted by giant fishes. Joaquin Torres and Nicole Wiesner round out the ensemble as John the Fisherman and the second Mary.

PASSION PLAY is three plays within a play as well as a lot of glimpses behind the scenes in three separate time frames. Everyone who sees this play will see something different, but no one will walk away unaffected.

TimeOut Chicago, Christopher Piatt – Were but passion enough. In an attempt to address the Bush era’s treacherous, licentious integration of governance, religion and art, Sarah Ruhl’s century-scanning work examines troubled productions of the Passion play in Elizabethan England, post-Weimar Germany and 1970s South Dakota. Using several dramatic tools of her generation—unchecked whimsy, ironically misplaced historical figures, antitheatrical technology—Ruhl’s play somehow manages to suggest perversion, despotism and gigantic floating fish without dramatizing any of it onstage. Well, that’s not technically true—the giant fish make several appearances. Although the three-and-a-half-hour run time could exhaust the patience of a Trappist monk, this glacial indulgence isn’t the problem. Unlike, say, Lanford Wilson’s Book of Days, in which the essence of Shaw’s Saint Joan reverberates in the lives of the Missouri community-theater enclave producing it, the Passion’s themes never resonate among Ruhl’s characters; even though they speak at length about it, they speak vapidly. (“No one actually wants to be Christ, they only want to admire him from a distance,” is about as deep as it gets.) To be fair, however, if Ruhl ever writes the inevitable play about putting on a play, she’ll be well armed; her eye and ear for the neuroses of show people are razor-sharp. Wing-Davey’s production can’t make heads or tails of the script’s detached imagery (all those toy ships on sticks evoke, at best, a grade-school Columbus Day pageant), but the director is certainly adept at handling actors with eccentric gifts. Nicole Weisner, usually seen on the tiny stage of the Eurocentric Trap Door Theatre, is note-perfect as a sappy ’70s Jesus freak, while Craig Spidle’s three stage directors are each uniquely fussy and funny. And spectacular stage creature T. Ryder Smith leaves mouths agape as Queen Bess, Der Führer and the Gipper. But the predictably oppositional perspective is toothless—those Nazis were so intolerant of homosexuals, and was President Reagan flaky or what?—and village-idiot characters (played by Polly Noonan) meant to act as each era’s conscience simply come across as infantilized. As a play, it’s merely an overwrought misfire. As an event that professes to speak to the moment, it’s a charade.

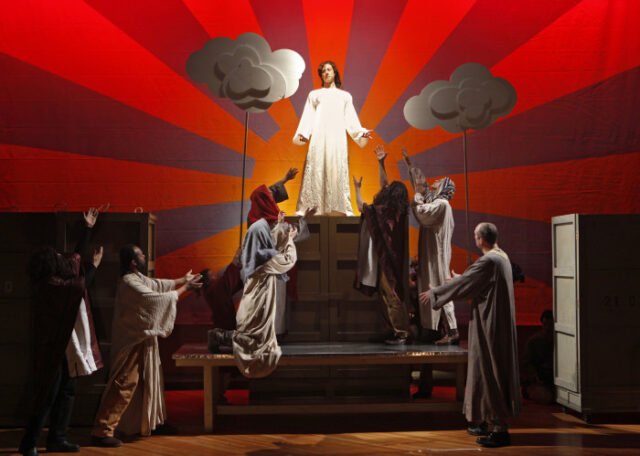

Variety, Steve Oxman – First, there’s the sheer ambition of the thing. Sarah Ruhl’s “Passion Play,” which she began over a decade ago as a playwriting student and has re-written since its initial premiere at Arena Stage in 2005, explores three communities in three different eras offering a production of the story of Christ, placing the story, and people’s relationship to it, amidst defined social contexts. Subtitled “a cycle in 3 parts,” the work takes on grand themes, particularly the nexus of religion, art and politics. In other words, it takes on the western world. Secondly, there’s the glorious dramatic poetry of the play. Just to give a single example, there are the human-sized dead fish, a parade of them in the first sequence, that then reappear in the final act. And let’s not fail to treasure a most redemptive ending, fully and beautifully staged by director Mark Wing-Davey in this lush production at Chicago’s Goodman Theater, in which a troubled Vietnam veteran (Brian Sgambati) who used to play Pontius Pilate ascends to the heavens in a giant ship. Since the arrival last season in New York of “The Clean House” after a multitude of regional productions, Ruhl is now fully recognized as one of the most exciting young voices in American playwriting. While it’s simply too big, and maybe even too thematically unwieldy, to find the same wide degree of exposure, “Passion Play” certainly won’t diminish her reputation. The theatrical conceit has actors associated to the same roles in each of the pieces — Joaquin Torres, for example, plays the characters who have been cast as Jesus, while Nicole Wiesner takes on those who portray Mary Magdalene. It’s an interesting acting challenge that the ensemble lives up to, managing to find both the connections and the disparities that make each piece unique but connected. Work begins in Elizabethan England with the story of a passionate actress playing Mary the Virgin (Kristen Bush) who, enamored of the fisherman who plays Christ (Torres), instead becomes impregnated by the fish gutter who plays Pontius Pilate (Sgambati), to tragic consequence. This first piece is the one that could most rewardingly be produced on its own — it feels lovely and complete.

Then there’s 1934 Oberammergau, Germany, where the young, sensitive man taking on the role of Jesus from his ailing father ends up — what else? — a Nazi. “You’ve got a new costume,” the Village Idiot (a constantly affecting Polly Noonan) says to him at the end of the act, seeing him in uniform rather than a flowing white robe. “It’s ugly.”And finally, there’s the Passion Play as produced in Spearfish, South Dakota, first during the Vietnam War and then in the 1980s. The oddly poetic young husband, an unlikely Pilate, goes off to war, returns to discover a personal betrayal, and then struggles for decades to wipe away his demons. Each act also portrays the leader of the day, with Queen Elizabeth, Hitler and Ronald Reagan making appearances, all played with a nimble mix of style and conviction by T. Ryder Smith. It’s a lot to ponder, a provocative and enjoyable 3½ hours of rich human yearnings and highly literate thematic layering. Ruhl observes the deeply convoluted interaction between the artifice of acting and that of politics — Elizabeth bans the Passion because people shouldn’t pretend to play Christ, and yet she herself takes pride in her own artificiality; Reagan, himself an actor, refers to leadership as a type of pretense; Hitler, well, he just says it all upon watching the blatant anti-Semitism of the Oberammergau passion: “How I love the theater.”

In addition to the big political questions, Ruhl also asks big existential ones, like how do the roles we play affect who we are? Wing-Davey and his team of talented designers (including eye-popping projections from Ruppert Bohle) infuse all with flourishes that seem at once simple, whimsical and profound, which nicely sums up a few core qualities that make Ruhl so special. Does it all work? Not completely. The third part, which has been the focus of her changes, doesn’t quite let us into its main character’s soul deeply enough to generate the emotional connection it should, coming off heady when it should be heartbreaking. But the beauty and thoughtfulness in “Passion Play” overwhelm all quibbles. 9.23.07

Windy City Times, Jonathan Ararbanel – Religion and politics have been one and the same until relatively recently. Governments supported a state-sanctioned faith or were out-and-out theocracies. Today’s global resurgence of theocratic politics is the greatest extant threat to democratic pluralism and individual liberty.

Shining young playwright Sarah Ruhl, a MacArthur “Genius Grant” recipient, tackles religion and politics head-on in her sprawling Passion Play, but she personalizes her tale, so it’s about individual faith more than formal religion. She eschews obvious preaching or debate, yet there’s a party line espoused in each of the play’s three parts, respectively set in 1575 England, 1934 Germany and 1969 South Dakota. In each, a historic political leader appears, God-like, to lay down political articles of faith.

In late medieval Europe, the life of Jesus—Annunciation to Ascension—was dramatized in so-called passion plays that became massive pageants involving most of a town’s citizenry and craft guilds under Catholic Church direction. Later, these epic shows became secularized, and continue today ( even in the United States ) often as summertime, outdoor spectaculars. Ruhl uses productions of the passion play to comment on the intersection of faith, politics and sexuality in three different eras. What if Pontius Pilate marries the Virgin Mary ( that is, the actors playing them ) ? What if Jesus has a Nazi boyfriend? What if Mary Magdalene really is a prostitute? Passion Play is ambitious and complex, and director Mark Wing-Davey has used Ruhl’s long-but-barebones text to create a modern theatrical pageant, layered with visual effects and technical devices—some as old as passion plays themselves—and a cast of 16. It’s dazzling and impressive, but it doesn’t all work because the three-and-half hour show ( two intermissions ) doesn’t have a gut-wrenching emotional climax.

It appears Ruhl has taken on more than she can effectively sustain. The third part especially, set in South Dakota during/after Vietnam, is too long and the least effective. The God-like spokesman, Ronald Reagan, is too much present and too clownish vs. the earlier appearances of Hitler and Elizabeth I. Ruhl’s time-leaping, history-inspired work compares well to some Tom Stoppard plays, but Ruhl doesn’t yet have Stoppard’s intellectual and theatrical mastery. Wing-Davey compensates by making each successive part more elaborate than the one before, adding quasi-magical flourishes—model ships, giant fish, striking projections—not required by the script. Eventually the size of his production consumes the play, which isn’t of sufficient dramatic weight to hold it all up. Wing-Davey is brilliant at bringing out unexpected comedy, especially in Part One and in Ruhl’s affectionate jests at theater itself, but he sacrifices character depth in the process. The large canvas Ruhl attempts to paint may be too vast for complete success, but her effort is worthy, intriguing, entertaining and admirable nonetheless. Artists always should think Big. 10.3.07

[previous] [next]