Photos by Maria Baranova.

Excerpts from reviews

“Masciotti mines the banalities of everyday chatter for heroic poetry. . . . Its plot — and it has more of one than this writer usually provides — vaguely recalls a multitude of stories in which a vulnerable old woman is fleeced by a younger predator. The wolf, in this case, is June’s landlord, Wayne (an enjoyably spasmodic Mr. Smith), a disgraced and self-medicating former podiatrist, who makes nice with his tenant while skimming from her Social Security payments. Another neighbor, the kindly Sissy (a warm and weary Ms. Hopkins), a Greek-born masseuse, tries to keep a lookout for threats to June’s well-being. . . . The play’s story and speech may be naturalistic, but its staging is not. . . . The cast members move in ritualized, sometimes synchronized steps that evoke a sense of life as an instinctive and repetitive dance. Objects under discussion — like frozen TV dinners, bunches of bananas and a lone credit card — materialize on cue from the vertical louvers at the back of the stage. . . . Sara C. Walsh’s set is divided into three stark, blank sections of beige carpet, well-worn linoleum and tiled fake wood, suggesting an anonymous wasteland of cheap housing. And there’s a gnatlike buzz of ambient noise by the great sound designer Ben Williams, a blurry aural backdrop to all the talk. . . . June is not unlike that eternal chatterbox Winnie, buried up to her neck in sand in Samuel Beckett’s “Happy Days,” a person for whom there’s life as long there’s talk. . . . June, too, becomes an existential heroine of sorts, a life force that persists even as it drifts into nothingness.” Ben Brantley, New York Times

“A sly comic thriller . . . Masciotti uses her keen ear for inflection, malapropism and dialect to [create] a wonderful stage creation. . . . The writing is superb, simultaneously unforced and lyrical. Masciotti does a magic trick, in which language as it is spoken somehow becomes poetry. The comedy is immediate, but the drama emerges imperceptibly, a slowly dawning realization . . . As counterpoint to the naturalistic dialogue, director Paul Lazar has the actors move in stylized gestures: Hopkins dashes in circles around an easy chair; Smith dismounts a table in the wriggly, legless way an alligator would. The performers (all veterans of movement-theater work) handle this juxtaposition with droll grace; in fact, all three do some of their best work here. . . . Hopkins is one of the best performers in the city . . . Elizabeth Dement is a serious midcareer dancer-performer . . . And diabolical T. Ryder Smith—the creepier John Waters, the oozier Steve Buscemi—is easily on my 10 Best Actors Alive list . . . Now New York’s weird tendency to undervalue its treasures is actually working in your favor. . . . a downtown supergroup is performing a gorgeously pitched, affordable show . . . “ Helen Shaw, Time Out New York

“We listen to June’s monologic wellspring of domestic, material obsessions — an immersion into her consciousness that becomes a neo-expressionist étude of blue-collar struggle. . . . Director Paul Lazar brings a gestural life to his staging, giving the performers’ choreographed movements and steps a dance-theater feel. (The actors might lie face-down on the carpeting or splay themselves sculpturally along the wall, embodying the submerged mood of a scene.) The cast, all downtown theater veterans, walk a thin line between character types and expressive depth — especially Dement, who shuffles around the set in a wig and oversize specs while talking nonstop. But in the dramatically forced final scenes, caricature prevails. Wayne’s prolonged meltdown and ultimate showdown with Sissy overshadow the more nuanced early detail. . . . “ Tom Sellar, Village Voice

“This deeply human play is staged by Paul Lazar as a circus act, avant-garde movement piece and thriller all bundled up into one. . . . Masciotti’s language brings to mind the deeply beautiful poetry of the everyday, a transcendence of words that soothes you with its banality, stings you with its heartache of loss, and cracks open your ear to the world around you. . . . June is played with incredible depth and detail by Elizabeth DeMent . . . Among those in her life are Wayne (an impressively nimble and sinister T. Ryder Smith), her cheapskate landlord who steals a percentage of June’s social security checks, and Sissy (Cynthia Hopkins in an hilarious deadpan turn) a loyal Greek massage therapist who takes care of June. When Wayne’s desperation for money overwhelms him, a diabolical plot is hatched . . . “ Teddy Nichols, New York Theatre Review

Video

Dress rehearsal photos

Above photos from a dress rehearsal by Eva C. Scanlan and Annabella De Reo

(Show design incomplete)

Pictured: Elizabeth DeMent, Cynthia Hopkins, T. Ryder Smith

Publicity

*

American Theatre magazine article:

The Cruel Humanity and Danger of ‘Social Security’ | AMERICAN THEATRE

*

Theatre Development Fund article:

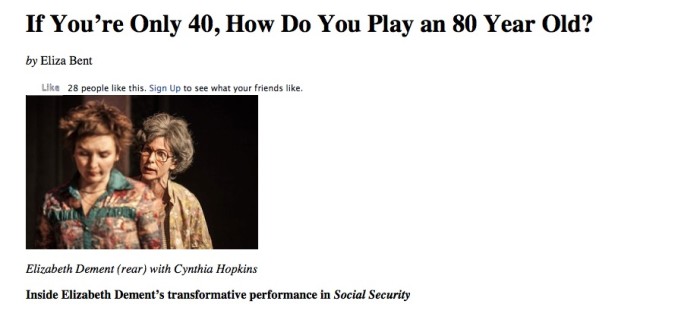

Elizabeth Dement is 40, but she plays 80

*

Bushwick Starr tumblr interview with playwright Christina Masciotti

Bushwick.Starr.tumblr.int.CM.SS

*

New York Times article about playwright Christina Masciotti:

Faces to Watch: Heroes, Sidekicks, Cartoonists – NYTimes.com

Rehearsals

Row 1: Entryway; Christina Masciotti, Paul Lazar.

Row 2: Paul Lazar; Ben Williams and Derek Spaldo; Liz DeMent and Paul.

Row 3: Paul, Liz, Cynthia and T rehearsing.

Row 4: Paul, Liz, Cynthia and T rehearsing.

Row 5: Paul, Liz and Cynthia rehearsing.

Row 6: Paul, Liz and Cynthia rehearsing.

Row 7: Props; Derek Spaldo; Christina and Derek.

Row 8: In the theater.

Row 9: Blocking and notes.

Row 10: Pincurls, table dismount, and more notes.

Row 11: Paul grabs a nap on break; Christina adjusts fishbowl of coins; dream.

Row 12: Blocking; theatre was cold; testing a wig.

Row 13: Dismount in costume; new wig; tech.

Row 14: Liz; Christina; Cynthia.

Row 15: The exceptional PA James Zebooker; pre-show light fix; Liz warming up.

Row 16: Weather; entry; final word.

Opening

Left to right: Jennifer Conley Darling, Christina Masciotti, Paul Lazar, Sara C. Walsh, Ben Williams (top), T. Ryder Smith, Elizabeth DeMent, Eva C. Scanlan, Simon Harding, Cynthia Hopkins.

Playscript

Reviews

New York Times, Ben Brantley – The Heroic Poetry of Solitude. She enters muttering, as if speaking without pause were as necessary as breathing. All subjects are given the same weight in June’s rushing river of words: the death of her husband, chocolate peanut butter Easter eggs, her most recent surgery, the virtues of Lysol and the dubious hygiene of the people next door.

Played with unconquerable garrulousness by Elizabeth Dement in Christina Masciotti’s “Social Security,” at the Bushwick Starr, June is one of those souls who has nothing to say and never stops saying it. No matter that this newly widowed, retired pretzel factory worker is almost entirely deaf and lives alone. The conversation must go on.

You probably know someone like June, quite possibly within your own family. And you have probably determined that the best way to survive time in this person’s company is to tune out as completely as possible. But Ms. Masciotti would like you to keep your ears open, for once. This dramatist’s implicit thesis is that if you listen closely enough, there’s significant artistry in insignificant talk.

As in her earlier plays, “Vision Disturbance” and “Adult,” Ms. Masciotti mines the banalities of everyday chatter for heroic poetry. Set largely in working-class Pennsylvania, in towns forgotten by time, her uneventful dramas seem to be composed of what might be called “found conversation,” of words taken directly from life, with only minor cosmetic alteration.

This may sound like your idea of hell. But there’s a determined empathy in Ms. Masciotti’s work that enlivens the senses, making you realize that nothing and no one is boring — once you’re forced to pay close attention.

Directed by Paul Lazar with a cast rounded out by the avant-garde theater veterans Cynthia Hopkins and T. Ryder Smith, “Social Security” is both more conventional and experimental than Ms. Masciotti’s previous work. Its plot — and it has more of one than this writer usually provides — vaguely recalls a multitude of stories in which a vulnerable old woman is fleeced by a younger predator.

The wolf, in this case, is June’s landlord, Wayne (an enjoyably spasmodic Mr. Smith), a disgraced and self-medicating former podiatrist, who makes nice with his tenant while skimming from her Social Security payments. Another neighbor, the kindly Sissy (a warm and weary Ms. Hopkins), a Greek-born masseuse, tries to keep a lookout for threats to June’s well-being.

What suspense the story has comes from their half-formed battle of wills over an old woman’s destiny. June doesn’t seem to make moral distinctions between them. As far as she’s concerned, each is a set of ears of equal value, receptacles for her contentedly oblivious monologues.

The play’s story and speech may be naturalistic, but its staging is not. Sara C. Walsh’s set is divided into three stark, blank sections of beige carpet, well-worn linoleum and tiled fake wood, suggesting an anonymous wasteland of cheap housing.

The cast members move in ritualized, sometimes synchronized steps that evoke a sense of life as an instinctive and repetitive dance. Objects under discussion — like frozen TV dinners, bunches of bananas and a lone credit card — materialize on cue from the vertical louvers at the back of the stage. And there’s a gnatlike buzz of ambient noise (by the great sound designer Ben Williams), a blurry aural backdrop to all the talk.

Some of these theatrical elements are more distracting than illuminating. (It’s never a good sign when you realize you’re furrowing your brow over choices in staging.) But to my surprise, I remained absorbed by Ms. Masciotti’s logorrheic characters, especially June, whom Ms. Dement endows with a rapt self- involvement that is improbably free of narcissism.

June is not unlike that eternal chatterbox Winnie, buried up to her neck in sand in Samuel Beckett’s “Happy Days,” a person for whom there’s life as long there’s talk. June is, in her less symbolic way, as immobilized as Winnie is. And as her tongue keeps flapping, she, too, becomes an existential heroine of sorts, a life force that persists even as it drifts into nothingness. 2.26.2015

Time Out New York, Helen Shaw – A woman putters around the stage, adjusting a paper grocery bag from Giant, plugging in a clock radio. We can hear an old woman’s voice nattering away on a recording (“And then he took all the black forks! You know my black forks”), and slowly—as she dons a saggy bra and wig—young Elizabeth Dement becomes 80-year-old June, waddling slightly in her baggy shorts and curly gray ’do. Under her breath, Dement takes over June’s running patter, picking up from the real recording. In a way, this is what playwright Christina Masciotti has done in the sly comic thriller Social Security, using her keen ear for inflection, malapropism and dialect to convert her own mother’s actual neighbor into a wonderful stage creation.

June recently lost her husband to cancer, but she’s surrounded by people who seem willing to help. Her disgraced-podiatrist landlord, the mustachioed Wayne (T. Ryder Smith), and her massage-therapist neighbor Sissy (Cynthia Hopkins) drop by constantly, so they can take June to get groceries (“Oh! We should get them Jell-Os with the fruit in ’em!”) or to the bank to cash her social-security checks. They’re willing to lean in close to June, who is deaf as a post, writing her notes and negotiating her strangely prickly dependence. The comedy is immediate, but the drama emerges imperceptibly, a slowly dawning realization that Wayne’s generosity isn’t all it seems. “He grew up in a cave by wolves,” warns Sissy. “Very quiet, very low-key wolves.”

As counterpoint to the naturalistic dialogue, director Paul Lazar has the actors move in stylized gestures: Hopkins dashes in circles around an easy chair; Smith dismounts a table in the wriggly, legless way an alligator would. The performers (all veterans of movement-theater work) handle this juxtaposition with droll grace; in fact, all three do some of their best work here. Even if you’ve seen Hopkins elsewhere, you might not have known she was capable of this level of cinematic realism; if you’ve known Dement as a dancer, you’ll be floored by her confidence and deftly funny touch here.

Masciotti’s writing is superb, simultaneously unforced and lyrical. As in Vision Disturbance, she does a magic trick, in which language as it is spoken somehow becomes poetry. Sissy, her Greek accent pushing her English into lovely shapes, mutters, “Life is too soon…too sure? Too short,” as she tries to nudge the dawdling June into action. And Masciotti deserves a prize for putting a retired pretzel-machine worker center stage, for figuring a way to write an entire play about how money changes hands in America that seems truthful and wry.

I love The Bushwick Starr. It’s one of the experimental scene’s best jewel boxes—or, more accurately, it’s a good old-fashioned, rough-hewn wooden box, which sets off jewels to best advantage. But in some ways, I regret that our theater economy is so topsy-turvy that such jewels, such rubies beyond price, are here, up steep stairs in Bushwick and selling tickets for only $18 a pop. Cynthia Hopkins is one of the best performers in the city—her own music-theater creations (Must Don’t Whip ‘Um, among others) changed the form. Elizabeth Dement is a serious midcareer dancer-performer, last seen at BAM. And diabolical T. Ryder Smith—the creepier John Waters, the oozier Steve Buscemi—is easily on my 10 Best Actors Alive list. (I keep it on a Post-it.)

But okay. There should be no reason to complain that a downtown supergroup is performing a gorgeously pitched, affordable show, where the audience can snuggle right up against them in a welcoming venue. I spend a lot of time whining that great work goes unseen because it costs too much (hello, Hamilton) or plays too short a time (Gob Squad, you scamps) or has some flaw in execution. Now New York’s weird tendency to undervalue its treasures is actually working in your favor. You must go! And how nice that Social Security makes it easy for you: A terrific production has written you a check, and you just need to take the L train out to Jefferson to cash it. 3.3.2015

New York Theatre Review, Teddy Nichols – “ . . . and yes I said yes I will Yes.” Among the great many female characters in modern drama–Molly Bloom from Ulysses, Lil Bit from How I Learned to Drive, Marge Gunderson from Fargo–June, the protagonist of Christina Masciotti’s Social Security, proudly stands among them. Complex, funny and heartbreakingly frustrating, June is endlessly engaging, filled with such specific detail of the human experience you might wonder if Masciotti simply transcribed an actual woman’s life onto the page.

June (played with incredible depth and detail by Elizabeth DeMent), a seventy year old woman rambling in her Pennsylvania Dutch to anyone who’ll listen (and even no one when no one is present, the absence of people is presence enough for June), lives a quiet life of domestication. Among those in her life are Wayne (an impressively nimble and sinister T. Ryder Smith), her cheapskate landlord who steals a percentage of June’s social security checks, and Sissy (Cynthia Hopkins in an hilarious deadpan turn) a loyal Greek massage therapist who takes care of June. When Wayne’s desperation for money overwhelms him, a diabolical plot is hatched involving a dog and an insurance policy.

As directed by Paul Lazar–who brings his choreographic eye from Big Dance Theatre, his dance-theatre company–Masciotti’s deeply human play is staged as a circus act, avant-garde movement piece and thriller all bundled up into one. And while most of the movements are gracefully bizarre which illicit giggles, sometimes it distracted from the more human elements of Masciotti’s language which brings to mind the deeply beautiful poetry of the everyday, a transcendence of words that soothes you with its banality, stings you with its heartache of loss, and cracks open your ear to the world around you.

Much credit must be given to Jacob A. Climer for his deceptively simple costume design and J. Jared Janas for hair and make up. Together, they transform the forty year-old Dement into a wholly believable seventy year-old woman. But matched with Masciotti’s language, Dement brings to life right before our eyes a woman I’ll not soon forget, a truly modern heroine of our time. 2.5.2015

Village Voice, Tom Sellar – There’s More to Christina Masciotti’s Social Security Than Meets the Ear. “Everything happens to us. The good ones,” June (Elizabeth Dement) complains. That’s how it goes in old age: The body starts to fail and the mind can become susceptible. You start to catalog life’s deficiencies and a day can seem like a marathon of tribulations. For June, a Pennsylvania widow who used to run the machines in a pretzel factory, those woes include deafness, high blood pressure, and a slowing walk.

She contends with other misfortunes: confusing new rules at the bank where she cashes her checks. Baffling paperwork. An apartment in disrepair. Stifling summer heat. Her doctor wants to change her diet. And her manipulative landlord Wayne (T. Ryder Smith) pinches pennies and filches from her Social Security payouts to fuel his own habits.

Christina Masciotti’s Social Security, a studious new play at the Bushwick Starr, trains our attention on this faltering, self-absorbed heroine for most of its 90 minutes. June mumbles and frets, speaking sometimes inaudibly to herself and then too loudly to others. We listen to her monologic wellspring of domestic, material obsessions — an immersion into her consciousness that becomes a neo-expressionist étude of blue-collar struggle. With all the canned groceries and an ever-present muffled background soundtrack by Ben Williams, we could be back in the 1970s watching a Franz Xaver Kroetz drama of anguished kitchen-oven realism. Closer to home, the play returns to territory explored by María Irene Fornés, who recharted American naturalism starting in the 1960s, fusing dark domestic relationships and poverty themes with language experiments.

Masciotti’s earlier play Vision Disturbance explored very similar social psychology but with more power and sharper form. (Experimental director Richard Maxwell created that 2010 production with his signature use of muted affect.) Two contradictory impulses run through Social Security: On one hand the playwright puts everyday language and characters onstage and steeps us in apparently banal thoughts to show human drives underneath. At the same time, Masciotti spins a straightforward narrative. A triangle emerges in which June’s neighbor Sissy (Cynthia Hopkins), a Greek massage therapist, comes to her elder’s aid. Until the dramatist inserts a traditional plot device late in the play — an “accidental death” insurance policy that might decide the protagonist’s fate — Social Security shares character information with subtlety. We learn of Sissy’s good heart and Wayne’s villainy, and we observe, repeatedly, how the preoccupied and pragmatic June fails to acknowledge either.

Director Paul Lazar brings a gestural life to his staging, giving the performers’ choreographed movements and steps a dance-theater feel. (The actors might lie face-down on the carpeting or splay themselves sculpturally along the wall, embodying the submerged mood of a scene.) The cast, all downtown theater veterans, walk a thin line between character types and expressive depth — especially Dement, who shuffles around the set in a wig and oversize specs while talking nonstop. But in the dramatically forced final scenes, caricature prevails. Wayne’s prolonged meltdown and ultimate showdown with Sissy overshadow the more nuanced early detail.

Despite the limitations, Masciotti seems poised to coax American domestic drama into rigorous and unsettling terrain, and her collaborations with bold directors make for a promising start. Pay heed to a neglected woman’s mutterings, the playwright implies, and you might be surprised by what you hear. 3.4.2105

Artforum magazine, Claudia LaRocco – Silly Writer Construct: See two plays, one written by a woman and directed by a man, the other vice versa. Discuss within larger context of progressive New York performance.

Shows in Question: Social Security, at The Bushwick Starr, written by Christina Masciotti and directed by Paul Lazar, performed by Elizabeth DeMent, Cynthia Hopkins, and T. Ryder SmithRunning Away From the One With the Knife, at The Chocolate Factory, written by Aaron Landsman and directed by Mallory Catlett, performed by Kate Benson, Juliana Francis Kelly, and James Himmelsbach.

Post-Performance Reality (aka Mostly Non-Construct Observations): There is the almost-identical table in both shows. I notice this Friday night on my way out of the Chocolate Factory, with a happy little shock of recognition. I like this table detail a lot. Rusted legs, curving rectangular top. Slight variations on a theme. Thinking about the ways in which artists send messages to each other, embed secrets, within their work. Sara C. Walsh designed the Social Security set, and Running Away was created by Jim Findlay, who also did sound design.

Both worlds are beautiful, unexpectedly, and hard. Walsh makes the stage into a triptych, beige layer cake of faux-everything: wall-to-wall carpeting, linoleum, floorboard laminate. Canned food. Findlay gives us the illusion of movement within stasis, freestanding, semitransparent walls that open and enfold, disgorging from various compartments cheap coffee and chemical cleaners. Perfection (fetishization?) of a sort of barren junkiness—post avant-garde NYC aesthetic?

Or maybe post-comfort. There’s nothing to hint at the possibility of change for the better in these productions, both of which (spoiler alert) zoom toward the death of a central character, each possessing a certain empty charisma.

Compare and contrast: In Landsman’s play, Christina (Benson) is the one with the knife, and she will eventually find a way to use it (or the next best tool) on herself. Masciotti’s victim is June (DeMent), and she’s also a talker—unlike Christina she doesn’t spin hypothetical death futures, but run-together memories of the past.

They both have manipulative relationships with handymen who aren’t quite handymen. In Masciotti’s script (gender-schema alert), the man does the manipulating; in Landsman’s, the woman.

(In Catlett’s production, my sympathies flew toward Himmelsbach, a man; in Lazar’s, toward Hopkins, a woman. Audience gender schema? Anyway, the acting is grand.)

They both talk too much. They talk more than they have things to say. Dry rub of habit. Ways to inflict pain, maybe, or to keep it at bay.

Language & Narrative P.S.: Structure is a messy business. “The murkiness and ambiguities of a life take on weight and authority by virtue of the published document,” Moyra Davey writes in the opening of Burn the Diaries (2014). I think I think that this is the same whether the life is imagined or actual (which anyway isn’t a black-and-white distinction, as we all know all-too-well by now—is that especially true in the theater?).

Both Social Security and Running Away From the One With the Knife resist, or seem to resist, conventional expectations up until the final stretches, at which point they lurch into, as my guest at one of the shows put it, the territory of a Meryl Streep drama.

Is this a strategy, a failure of nerve, both? Or does it rather say something about the ways in which artists are now relating and/or responding to something in the water?

Are these useful questions? It’s very easy (see “Silly Writer Construct”) to have an idea about how to proceed when you’re following in someone else’s footsteps. It’s very easy to make up your mind, so much so that when time-based art foils this interior audience process it can take a moment to realize you should be grateful.

But also, of course, at what point do the ways in which we resist conventional expectations become the new conventions, and why do we remain stubbornly programmed to see this as a bad thing? Or do we?

Running Away uses a live pop performance (music by Christian Gibbs, performed with Anton Sword) to tie up some of its loose emotional ends, and Social Security employs a sound score (by Ben Williams) for plot shorthand. The music is a trope, one that somehow manages to keep satisfying, despite (here I suspect individual audience-member weakness). The Social Security shorthand felt less adequate. Both, of course, are overt turns away from the self-sufficiency of language, that good old illusion which is never, ever, gone for good. 3.24.15

[previous] [next]