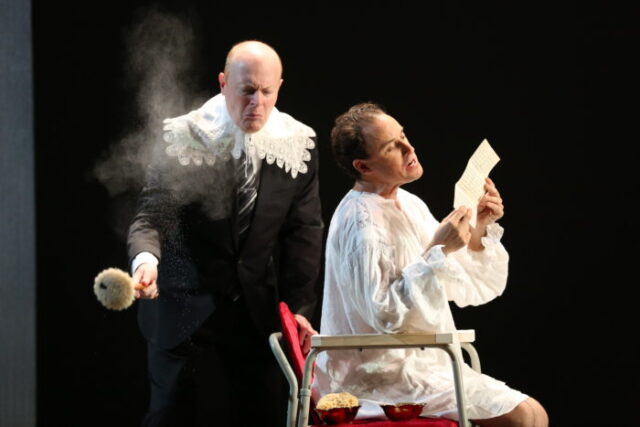

photos by Carol Rosegg.

Excerpts from the reviews

“In many ways, Scenes From Court Life resembles a modern Elizabethan masque, that ingenious party-procession-play mash-up that delighted royal audiences for generations. . . . It contains comedy, tragedy, mythology, ceremony, fashion, pageantry, poetry and song. . . . This politically provocative show . . . sets up historical contrasts that explore the concepts of brotherhood, friendship, rivalry and parental expectations, within the greater context of famous powerful families. In both of the eras that the playwright examines, there are efforts at leadership, selfish displays of bravado at the expense of others, and crushing humiliations.”

– The Hartford Courant

“The plot juxtaposes the Bush family with the House of Stuart, Charles I sharing an actor with the elder George, Charles II with the younger, Jeb with the prince’s whipping boy, Karl Rove with the Groom of the Stool . . . . Ruhl’s visual wit and careful attention to the nuances of two overlapping sets of relationships makes for a rich and compelling family drama. . . . The Bush and Stuart plots aren’t exactly interwoven; rather, one milieu is constantly collapsing into the other. Occasionally, these switches are accompanied by costume changes or set cues; more often, they rely entirely on the extraordinarily talented cast’s ability to adopt different personas from minute to minute. Gradually, the distinction between past and present breaks down. Characters appropriate gestures or turns of phrase across time frames; frequently, a conversation begins in one era and ends in another. . . . Scenes From Court Life is not really about politics. Instead, politics is a vehicle for exploring the effects of power on fathers, mothers, sons, and — especially — brothers.”

– Yale Daily News

“Intriguing, funny and heartfelt . . . A welcome oasis for those parched from a lack of humanity during this election season. Ruhl’s incisive examination of political dynasties and sibling rivalry is the perfect balm to neutralize the stinging bombast and mendacity on one hand and the cramping, steely precision on the other. . . . As Ruhl lucidly draws them, the Stuarts and Bushes are uncanny counterparts. . . . Director Mark Wing-Davey and the cast land their laughs with a delicate touch . . . Ruhl’s play is gracefully touched by humor, heart and equal insight into human frailty and strength.”

– New Haven Register

“Immensely provocative . . . Ambitious, complicated, and politicized . . . A very full, political play . . . which ultimately denounces war . . . “

– Talkin’ Broadway

“Timely, entertaining and refreshing . . . T. Ryder Smith is brilliant as Charles I . . . ”

– Connecticut Arts Connection

“A wild ride . . . Takes us seamlessly and flawlessly, like a championship tennis match, back and forth across the centuries . . . Charles 1 and G. W. Bush are captured with majesty by T. Ryder Smith . . . A masterful piece of theatre.” – Connecticut Critics Circle

“A blistering satire . . . Bold and adventurous . . . Directed with deft precision by Mark Wing-Davey . . . The acting ensemble is first rate. T. Ryder Smith preens like a prize peacock . . . The ensemble breathlessly changes costumes and accents in what appears to be nanoseconds while the play careens and shifts like a runaway roller coaster . . . The play can be dizzying with the numerous time shifts and its messy structure can get convoluted and over-stated. How refreshing it is, though, to sift through an overloaded original work like this, full of ideas and current commentary that is rich, funny and humane all at the same time.”- Connecticut Post-Chronicle

“The problem with Ruhl’s time-skipping experiment is obvious: Why are these two stories being intertwined? . . . The harder Ruhl attempts to disclose (or force) similarities between the powerful then and now, the further away she gets from making substantial points, satiric or otherwise. . . . Fortunately Yale Rep’s cast and design team make up for the cartoon ennui considerably. The ensemble of eight principal actors are double and triple cast and portray a wide range of characters from both families. Familiar political archetypes are sent up in high, precise, and entertaining stylizations. The personalities of King Charles I and George Sr. are not all that charismatic, but there’s plenty of delight in watching how T. Ryder Smith portrays both characters . . . “ – ArtsFuse.org

“A funny, perceptive, scathing scatological screed . . . Placing the Bushes in historical context by comparing their machinations with those of Charles I and his son, Charles II, allows for political results that are both frightening and hysterically funny . . . Director Mark Wing-Davey sorts out the permutations with skill and a welcome light touch . . . In an excellent cast, T. Ryder Smith stands out as George H. W. and Charles I. Imperious but kind, a patrician not above grimy politics, his characters are complex and Smith fuses similarities and contradictions with the slightest gestures . . . “ – Curtain Up

“Today, most of us — audiences, artists, critics — are aware that our “nature” is almost inextricably fused with our politics. Therein lies the purpose behind this arch and suggestive comedy by Sarah Ruhl . . . Thoughtful, a bit precious, and a lot of fun to watch, Scenes of Court Life is anything but escapist theater. . . . As elder Bush and elder king, T. Ryder Smith is remarkable, playing both roles with studied dignity and subtle obtuseness that goes a long way to making the parallel work on stage. His is a wonderful portrait of the aging former president Bush. . . . “ – New Haven Independent

Rehearsals and Offstage

Publicity

Full reviews

Yale Daily News, Clara Collier -“Scenes” Serves Presidential Intrigue. It would be easy to mistake Scenes From Court Life, or The Whipping Boy And His Prince, Sarah Ruhl’s new play at the Yale Repertory Theater, for heavy-handed political satire. The plot juxtaposes the Bush family with the House of Stuart, Charles I sharing an actor with the elder George, Charles II with the younger, Jeb with the prince’s whipping boy. (Karl Rove, in a lace collar and a starched expression, doubles as the Groom of the Close Stool, an attendant to the Stuart and Tudor kings responsible for — among other duties — determining fiscal policy and wiping excrement from the royal ass.) The commentary on American public life is both obvious and beside the point. Ruhl’s visual wit and careful attention to the nuances of two overlapping sets of relationships makes for a rich and compelling family drama.

The way Ruhl builds character is almost architectural — and architecture, incidentally, is a recurring theme. Both plots progress semi-linearly. The opening scene begins with a fairly typical psychological sketch of the Bush family, engaged in a tennis match at the family home in Kennebunkport, Maine. George Senior is genial and calculating, Jeb decent and somewhat pathetic. W., driven by a Freudian compulsion to win his father’s approval, is egotistical, insecure, petulant and frighteningly vindictive. The play circles around key moments, adding nuances to the family’s dysfunction like a series of watercolor washes.

The Stuarts, with the possible exception of Charles II, are not as psychologically complex as their modern counterparts. While Ruhl resists the temptation to indulge in cheap parallelism, and the two families have their own internal dynamics and major themes, the 17th-century characters are primarily foils for the Bush clan. The English Civil Wars prefigure American involvement in the Middle East — that’s what happens when family conflict is allowed to spill over into the public sphere.

Even so, Charles II’s coronation speech features the most politically relevant line in the play — “You wanted the glamour and certainty of kings,” he declaims. “Democracy — fucking bore, I tell you.” In context, it’s a comment on the Bush’s dynastic politics, but one can’t help but be reminded of another ostentatious would-be autocrat.

The Bush and Stuart plots aren’t exactly interwoven. Rather, one milieu is constantly collapsing into the other. Occasionally, these switches are accompanied by costume changes or set cues; more often, they rely entirely on the extraordinarily talented cast’s ability to adopt different personas from minute to minute. Gradually, the distinction between past and present breaks down. Characters appropriate gestures or turns of phrase across time frames; frequently, a conversation begins in one era and ends in another. At one point, Charles II appoints Dick Cheney to his privy council.

As the boundaries start to dissolve, the plot seems to resolve itself through a series of shared themes. The play is permeated by emotional and thematic leitmotifs — sibling rivalry, corporal punishment, blood and tennis are especially prominent. The structural complexity is admirable. Even more so is Ruhl’s dedication to puns. The title, of course, refers to courts both tennis and royal, and one particularly involved construction manages to incorporate the concept of perspective (in both art and politics), 17th-century stage design and the entire set for Act II. The fact that the opulent “close stool” of the Stuart kings — essentially a portable toilet — might be referred to in modern parlance as a “throne” hardly bears mentioning.

It’s probably a necessary consequence of such an elaborate narrative structure that certain elements don’t entirely cohere. Laura and Barbara

Bush, in particular, seem oddly disconnected from the events of the play. In their interactions with other characters, they’re politician’s wives — that is to say, gentle, supportive, unerringly and unnervingly cheerful.

Predictably, their monologues to the audience reveal a hidden inner strength and innate maternal aversion to their husband’s war-mongering. Their speeches are part of a string of associations between women, blood, miscarriages and victims of the Iraq War. All this keeps the war’s impact inside the scope of the play, which is that of a family conflict, but leads to somewhat confused gender politics. The introduction of the war theme creates a necessary imbalance — even if intrafamilial tensions are resolved, the stakes for the Bush family are never going to be as high as they are for everyone else.

This lack of political coherency is not a fatal flaw — because, after all, Scenes From Court Life is not really about politics. Instead, politics is a vehicle for exploring the effects of power on fathers, mothers, sons, and — especially — brothers. 10.7.16

–

New Haven Register, E. Kyle Minor – As the sparring presidential campaigns barrel towards the general election, Sarah Ruhl’s intriguing, funny and heartfelt play “Scenes from Court Life, or the whipping boy and his prince,” which officially opened Thursday at Yale Repertory’s University Theatre, is a welcome oasis for those parched from a lack of humanity during this election season. Ruhl’s incisive examination of political dynasties and sibling rivalry is the perfect balm to neutralize the stinging bombast and mendacity on one hand and the cramping, steely precision on the other.

“Scenes from Court Life,” a world premiere production kicking off Yale Rep’s 50th anniversary season and continuing through Oct. 22, is a splendidly crafted juxtaposition of the Stuarts — Charles I and Charles II, who ruled 17th century England as bookends to Oliver Cromwell’s Commonwealth — and the Bush Family, including George H.W.,

Barbara, George W., Laura, Jeb and Columba. One wouldn’t necessarily draw such parallels between the two families on one’s own. Yet as Ruhl lucidly draws them, the Stuarts and Bushes are uncanny counterparts.

Each set of father-son leaders had its succession interrupted (by Cromwell and Bill Clinton, respectively) and, if we’re to believe what we’ve read, the sons set out to win their dads’ love, resolve their unfinished business and avenge their fathers’ critics — in spades. Ruhl visits other similarities in personal family matters, such as the loss of a child and the political give and take between siblings, spouses and parents and their children. It is in this terrain — the private wars, conflicts and tiffs — that “Scenes from Court Life” deeply affects theatergoers, precisely because these episodes are nonpartisan, if not strictly apolitical.

Ruhl’s naked, unfettered look at these characters during their most vulnerable episodes compels audience empathy without solicitation. These scenes of human honesty surely pierce the armor of antipathy worn by even their staunchest detractors.

While these scenes give the play its heart, they are surrounded by humorous ones where the characters look and sound as they do in history books or in recent memory, as preserved by the mass media. Director Mark Wing-Davey and the cast land their laughs with a delicate touch, knowing that any whiff of hyperbole in mining such familiar landscape reeks of overkill, as when George W. blithely butchers the English language that would give Mrs. Malaprop pause. Here the gag hits the funny bone just so.

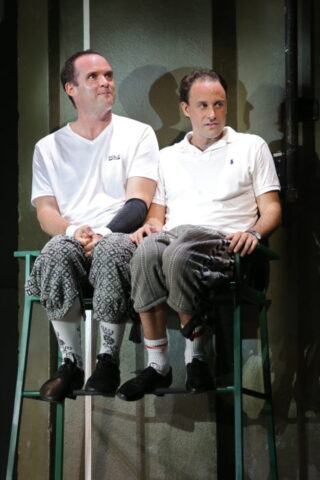

As for the actors, they all have at least a passing resemblance to their characters vocally and physically. More importantly, they communicate the essence and spirit of their characters, especially in their private lives. When Greg Keller’s George W. and Danny Wolohan’s Jeb fight during a child’s game of plastic army men, one’s hardly aware that they are grown actors pretending to be adolescent brothers quarreling as they often do because they are the embattled brothers.

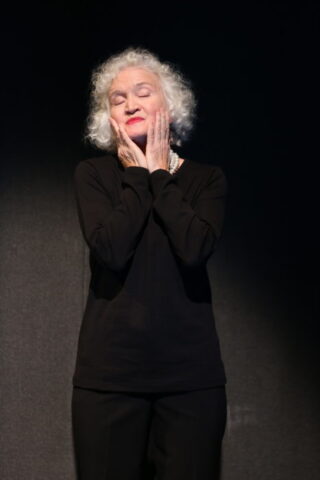

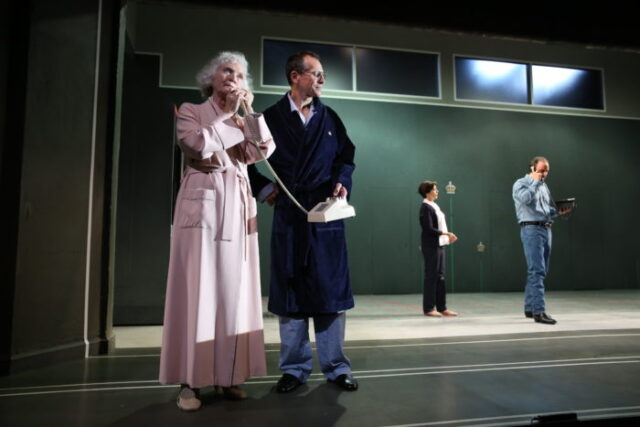

T. Ryder Smith, who plays the dual role of Charles I and George H.W. Bush) portrays his parts with equal dignity, as does Keren Lugo, doubling as Catherine of Braganza and Columba Bush. Mary Shultz’s Barbara Bush and Angel Desai’s Laura Bush wear the familiar smiles of their public personas yet bring such dimension and soul to these stalwart women that one wishes that either would run for high public office.

Jeff Biehl, who plays a spot-on Karl Rove as well as Groom of the Stool, Executioner and Donald J. Trump, shifts from one character to another with apparent ease while Andrew Weems likewise pops in and out as Tutor, Inigo Jones and Bonnie Flood, to name but three, with unforced élan.

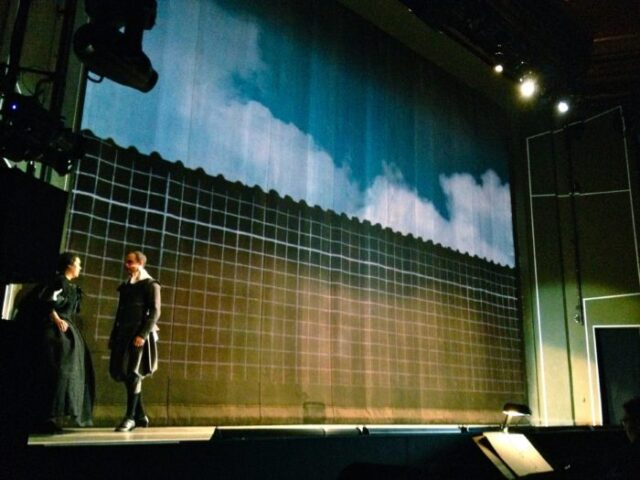

Yale Rep’s quality design team — Marina Draghici (scenic and costume design), Stephen Strawbridge (lights), Shane Rettig (sound designer), and Yana Birÿkova (projections) — exquisitely complement Ruhl, Davey-Wing and the cast, the production blinks from one place and time to other in full view so unerringly that when the stage actually goes black, it’s a visual punctuation mark to a memorable scene.

“Scenes from Court Life” is a veritable treat, a wonderful choice to open Yale Rep’s 50th anniversary season. It also marks Ruhl’s sixth production at Yale Rep, all of them different with the exception that they all are gracefully touched by humor, heart and equal insight into human frailty and strength. 10.10.16

–

Talkin’ Broadway, Fred Sokol – Sarah Ruhl’s new, immensely provocative Scenes from Court Life, or the whipping boy and his prince, at Yale Rep through October 22nd, juxtaposes the dynasty of Stuart Kings Charles I and II in seventeenth century England with America’s own Bush clan. The plot and the coming-together of this comic drama are collaborative. Ruhl works again with director Mark Wing-Davey, aboard for her 2008 Passion Play. Wing-Davey provided graduate acting students from NYU and the group researched topics including sibling rivalry (George and Jeb Bush), royal succession, and so on. The result is a very full, political play and one which ultimately denounces war.

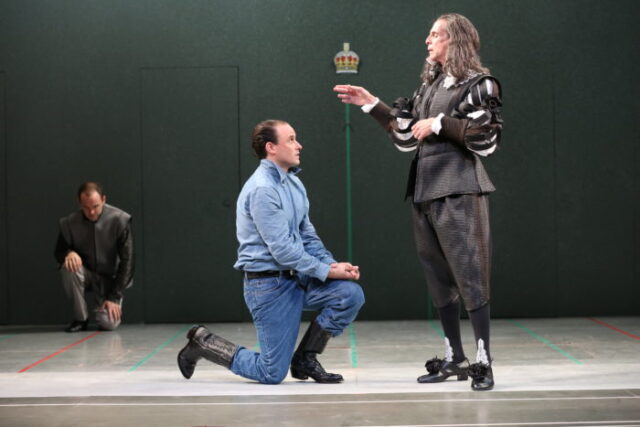

Ranging back into a time less familiar to many of us, Charles I (T. Ryder Smith) became a King in 1625. It was not until 1660 that his son Charles II (Greg Keller) came to power. Charles I was beheaded for treason. Charles II married Catherine of Braganza (Keren Lugo) but they were not able to have children. Ruhl has also written in Groom of the Stool (Jeff Biehl), whose job it was to tend the King. A Whipping Boy (Danny Wolohan) took all kinds of punishment.

Far more recognizable are George W. Bush (Keller), Jeb (Wolohan), George H. W. Bush (Ryder Smith), Barbara Bush (Mary Shultz), and Laura Bush (Angel Desai). Wing-Davey and his crew create imaginative tennis court play through simulation and sound. The Bush brigade is marked by those who had expertise, those who triumphed, those who won and lost, etc. Laura, by the way, is most often immersed in a book. Jeb, the younger and smarter and taller of his Bush generation, could not match George W. in terms of election to higher office. The elder George H. W. Bush doesn’t fare terribly well in Ruhl’s depiction. Of all, Keller’s spot-on accent and grasp of George W. Bush’s persona claim first prize for emulation.

The divine right of those families who inhabit highest office in a land becomes a focus. The first act of the play, spiced up with the tennis sequences, zips right by. Mary Shultz’s Barbara Bush is a deft tennis player! The first 25 minutes or so of the second portion of the play are expository and a bit slow. Not enough happens; Karl Rove (Biehl) gets some stage time—and then the action moves forward. A precious contemporary debate sequence between Jeb and Donald Trump is a brief, comedic highlight. Sarah Ruhl has said that she became agitated when Jeb Bush was trying to become the current Republican nominee, and she began to contemplate the implications of another Bush presidency.

As the play draws to a close, the playwright makes her feelings clear, through her scripting, that warfare is horrific. All say: “Let the politicians tell the the truth Let the actors all pretend.” Next, men add, “Let the fathers hold their children close. Let the wars come to an end.” At the very end, all declare: “If there be a Lord—Let the whipping end—Let the whipping end—Let the killing end.”

Ruhl and those who have been collaborative took on a great deal with Scenes from Court Life. Most of the strands of the play weave together. Humor helps and the Bush caricatures enrich the evening by providing another dimension. None of the men in that family receive favorable treatment. Laura seems to be a sane individual and actress Angel Desai, who plays Laura, opens the performance as a musician (not the Laura Bush character) who plays harpsichord.

Marina Draghici’s sets wonderfully fuel rather than overwhelm the production. Her choices for wardrobe enhance each of the time periods described. Greg Keller is dressed in George W. Bush garb during a moment when he is speaking as his other character, Charles II. This choice (utilized elsewhere, too) provides linkage between the depicted epochs. It is thoughtful and actually clarifies.

Scenes from Court Life is ambitious, complicated, and politicized. Sarah Ruhl is a gifted writer. My favorite of her plays is still Eurydice, at Yale Rep a decade ago. Now she examines, with sterling production and creative teams, ruling families. Intellect and imagination come together within the contexts of Yale Rep’s presentation. 10.10.16

–

Hartford Courant, Christopher Arnott – A provocative, political play. Donald Trump can’t let Jeb Bush alone.

The businessman-cum-politician makes a special appearance near the end of Sarah Ruhl’s new political-dynasty drama “Scenes From Court Life,” castigating him during the Republican debates.

We all recall Trump’s attacks, but Ruhl doesn’t bother to repeat the obvious catcalls, such as “low-energy.” She wants to remind us how Trump went after Jeb’s father and brother. She’s already reminded us how George W. Bush‘s impulsive decision to run for governor of Texas complicated his younger brother’s attempt to win the same post in Florida.

She mirrors the Bush brothers’ battles with episodes from the reign of Charles I and Charles II in Stuart-period Great Britain. There again, the issues aren’t about what one’s constituents (or royal subjects) think of you. It’s about how you’ve been treated by your father.

“Scenes From Court Life, or the whipping boy and his prince,” is receiving its world premiere at the Yale University Theater through Oct. 22. It’s a cutting-edge season-opener for the Yale Repertory Theatre. In this politically provocative show, the celebrated writer of “Passion Play,” “Eurydice” and “The Clean House” sets up historical contrasts that explore the concepts of brotherhood, friendship, rivalry and parental expectations, within the greater context of famous powerful families. In both of the eras that the playwright examines, there are efforts at leadership, selfish displays of bravado at the expense of others, and crushing humiliations.

The play sets up its chosen style immediately, as a courtly court dance morphs into a Texas-style country-pop line dance. Throughout the show, actors don and doff just enough clothing to suggest that the setting has moved from mid-17th century England to late 20th/early 21st century America. It features a busy cast of eight actors (one of whom, Keren Lugo, performed in an earlier version of the play, as part of an NYU student actor project), plus four others who act as bodyguards and furniture movers.

In many ways, “Scenes From Court Life” resembles a modern Elizabethan masque, that ingenious party-procession-play mash-up that delighted royal audiences for generations. One of the masters of that form, Ben Jonson, is mentioned in “Court Life” as “that idiot,” but the play does him proud. It contains comedy (including the obligatory stand-up act of egregious George W. Bush misstatement and phrase-manglings), tragedy, mythology, ceremony, fashion, pageantry, poetry and song. Mark Wing-Davey, the renowned British director whose previous Yale Rep credits include Ruhl’s “Passion Play in 2008, keeps the scenes sharp and distinct, with clear transitions despite the hectic shedding of outergarments.

The set design is clean and open. Actors grab costumes and props from a series of closed doors. Those props include such unpredictable objects as tennis balls, a silver top of a walking stick that comes unstuck, and a bucket of blood. The sound design by Shane Rettig is just as tricky: soundtracking everything from a tennis game to a decapitation.

The play doesn’t just feel current, it feels local. Both the British and American parts feature jokes about New Haven. “I was a history major in New Haven,” a laid-back George W. Bush explains. “That’s what people call Yale when they feel more comfortable in a Texas line dance than in the Eastern establishment.” He uses different gestures and mannerisms but lets each character directly inform the other. Danny Wolohan is the Jeb to Keller’s George W. and the Barnaby to his Charles II. Barnaby is portrayed as a best friend and confidant but also the designated “whipping boy” who must endure physical punishment whenever the prince does something wrong. A metaphor is extended by which Jeb Bush must suffer for the bad decisions of his brother.

There’s a whole other metaphor built into the show, where the respective fathers of the “princes” have a special relationship with their advisers. As “Groom of the Stool,” Jeff Biehl must wipe the ass of King Charles I (T. Ryder Smith). Biehl also plays Karl Rove to Smith’s George H.W. Bush.

The comparisons seem funny rather than forced. “Scenes From Court Life” has a lot to say about children of power and privilege.

This is a show about kings in their underwear, about victories ruined by a parent’s thoughtless remarks about family arguments and bedroom outbursts. “Scenes From Court Life” is scenes from family life. That makes for much better theater than any Trump cameo. 10.9.16

–

OnStage blog, Tara Kennedy – Never in my wildest dreams did I think that the Stuarts and the Bushes had anything in common. Luckily for us, Sarah Ruhl does imagine such things, and the result is the hilarious satire, Scenes from Court Life, a world premiere work at the Yale Repertory Theatre. The play is advertised as “History, remixed” which is an excellent way of describing Ruhl’s newest work. My only experience with her plays is The Vibrator Play, or in the next room which I thoroughly enjoyed. Ruhl’s bawdy banter is still present in this work, but with a number of broader messages dosed in smaller, bite-size portions.

The show opens with the cast in simple medieval dress performing a 17th century-style dance which suddenly morphs into a country line dance hoedown. It was perfect late 1980s-early 1990s country pop (think Billy Ray Cyrus). The mixing of these two dance styles set the mood for the Medieval Texas highball we were about to imbibe.

The play feels “vignette-y”: it feels like a number of scenes all put together, almost as improvisation, which is how the work was composed: riffing and remixing these two dynasties and seeing where the pieces fit. My husband was frustrated with this style. He felt like the scene would bring up interesting, poignant points and, as quickly as they arrive, they disappear, never to be mentioned again. I could see beyond that, as the performers and the director, Mark Wing-Davey, did a fantastic job weaving the stories together making it appear less abrupt than it might on paper. Honestly, I think it is the direction and the performers that make this play work.

The actors play multiple roles: to highlight the parallels and to interweave the plot because, as advertised, this is all mixed up. The plot follows the Stuarts after the death of James VI: the courts of Charles I (T. Ryder Smith) and Charles II (Greg Keller) were marked by internal strife due mostly to political and religious infighting. It was so bad that it resulted in the beheading of Charles I and the flight of his heir, Charles II, to Europe until things calmed down. The fictional element entwined into this plot line is a whipping boy, Barnaby (Danny Wolohan), who is Charles II’s best friend and confidant, despite having to take stinging lashes for the prince.

This is interwoven with loosely parallel stories from the American dynasty of Bush: George H. W. (Smith), Barbara (Mary Shultz), George W. (Keller), Jeb (Wolohan), Laura (Angel Desai), and Columba (Keren Lugo), including the political sparring of siblings George W. Bush and Jeb Bush, and their relationship with their parents, George H. W. Bush and Barbara Bush: some real, some imagined.

The Stuart story is at least somewhat based on fact: Charles I (r.1625-1649) had a bit of a time of it during his reign as King of England; there was lots of infighting in Great Britain during this period, mostly due to money and religion. Pro tip: if you are planning on being a king, it’s not a good idea to pick fights with Parliament. Charles I dismissed Parliament so many times that they got sick of it and decided to rise up against him, with Oliver Cromwell leading the charge. Charles I was beheaded for treason in 1649. His heir, Charles II, hid in Europe after his father’s execution, essentially to avoid the long Protestant arm of Cromwell. Once Cromwell died in 1658, Charles II was restored to the throne during the (aptly named) Restoration period. And unfortunately, he didn’t seem to learn from the sins of his father: he too kept dismissing Parliament on and off, and eventually dissolved Parliament during his final years of rule.

The actors were incredible: all of them. Having to switch accents, manner, language, clothes… they all do this with aplomb. They all embodied their characters without lampooning them; this was especially a challenge for Keller as George W. His brilliant performance was dead-on good-old-boy without being a caricature. Wolohan played the far more serious and earnest Jeb excellently. I also was impressed with Lugo’s portrayals of Catherine and Columba: juggling multiple languages in emotionally-charged scenes. Honestly, every actor gave great performances with roles that were extremely challenging.

Simple costume pieces leaned more toward the symbolic rather than the lavish. I can see why the color scheme of the clothing blended so well with the set design: Marina Draghici designed both costumes and set. The muted blues, grays, and greens mixed with some eye popping reds and the brilliant flourishing purple cape of Charles II all made for a lovely palette. I also loved how the costume and wig pieces were intermixed with the scenes: Karl Rove in a ruff collar, George H. W. Bush in Charles I’s foppish wig. Also, hats off to Shane Rettig’s sound design and its execution: syncing tennis lobs to the swing of actor’s racquets is no small feat.

This tight-knit ensemble gave a masterful performance, and I am kicking myself for not giving them a standing ovation. They so deserved it.

So why didn’t I stand up? Ladies and gentlemen, the ending was all wrong.

I can see where Ruhl was going and where the idea formed: the divine right of kings and the divine right of political lineage isn’t as far removed as we would like it to be. I also understand why the play had to change as it was being written: I recently read in an interview with Ruhl in the Hartford Courant that the play had been crafted with the assumption that Jeb would win the Republican nomination. That didn’t happen, so the show had to go in another direction. The loss of the more complete parallel between the Stuart and Bush dynasties made the ending sort of bewildering. This play is innovative in its historical remixing, so why create a conventional ending? Now, I suppose a medieval-styled war protest song at the end of a show isn’t necessarily a usual occurrence, but the song’s content was so mundane that it took the wind out of the show’s sails. It made the entire audience immobile so they couldn’t get up out of their seats, even if they wanted to. I even double checked the text to make sure I wasn’t misunderstanding. “Damn it! Sarah copped out!” I texted to my friend after the show, who was equally frustrated with the ending.

Ultimately, do I recommend it? Yes. Come see these marvelous actors who rock the Yale stage: it is engaging and fun, especially if you endured the Dubya era. They deserve to be seen and heard because these are performances that are out of the ordinary in terms of complexity. There is deeper significance in the lines and scenes, but don’t expect it to be a broad, cohesive message. This play might be best suited for those looking for entertainment rather than deep meaning. For me, that was fine, but I’m a shaken-not-stirred kind of gal. 10.9.16

–

The Balcony and Beyond, Bonnie Goldberg – Hold on tightly to your pogo or hockey stick, well, in this case, your tennis racquet, for 350 years of political history as innovative and imaginative playwright Sarah Ruhl hopscotches from the dynasties of the Charles Stuarts of Great Britain to the George Bushes of America in less than two and a half hours of creative theater telling at the Yale Repertory Theatre until Saturday, October 22. The world premiere of “Scenes from Court Life or the whipping boy and his prince” will surely open your eyes and mind to the startling revelations and similarities between these seemingly diverse historical families.

Yale Rep’s University Theatre takes us seamlessly and flawlessly, quickly and repeatedly, like a championship tennis match at Wimbledon or the US Open , back and forth across the centuries, from

King Charles I and his son, the royal prince Charles II, to American royalty George H. W. Bush and Barbara, sons George W. and Jeb and their spouses Laura and Columba. One moment you are dancing in the royal court and the next you are doing a Texas hoe down.

Keep your eye on the tennis ball as it bounces back and forth between the two stories as Greg Keller is alternately excellent as the young prince afraid of the crown he will soon wear and the ambitious son of a president eager for his chance to catch the golden ring on the merry-go-round. While Prince Charles has a whipping boy, Danny Wolohan, to take his punishment if he commits a sin, George W. has his younger brother Jeb, also brought to life by Danny Wolohan, to serve the same role.

In the early era, Charles I is accused of treason and beheaded and later number 41, President G. H.W. Bush counsels his sons on their positions of potential power. Both roles are captured with majesty by T. Ryder Smith. Mary Shultz is the loyal Barbara Bush, protective of her sons while Angel Desai serves a dual role as the harpsichord player who opens the scene and the supportive wife Laura.

Keren Lugo bridges the ages, first as the arranged wife of Charles II, as Catherine of Braganza from Portugal and later as Columba, the wife of Jeb. With our own contentious contest waging on our soil, it may be comforting to learn that “politics is essentially a tennis match. Some one wins and someone loses.” Mark Wing-Davey presides over a masterful piece of theater, rife with video projections and unusual props and properties, with an excellent cast of actors on both sides of the pond.

Come enjoy the sport of kings, admire George W’s artwork, be privy to the inner workings of two regal families and marvel at the genius of Sarah Ruhl.

–

Connecticut Arts Circle, Zander Opper – Sarah Ruhl’s “Scenes from Court Life (or the whipping boy and his prince)” is both a timely and time bending new play that is receiving its world premiere production at Yale Repertory Theatre. And though the show is slightly overlong, the playwright has a good deal of fun presenting both life amongst the royalty in 17th Century England and life during the years when the Bush family was in power in America. Director Mark Wing-Davey has done a fine job of jumping back and forth in time and it is always apparent onstage which era the audience is watching at any given moment. What’s more, the cast of “Scenes from Court Life” is certainly game and richly talented and are able to switch time periods within a single line. Sarah Ruhl has created quite a playful and unorthodox new work and, though it needs some editing, “Scenes from Court Life” may very well have a future life beyond Yale Repertory Theatre.

The plot, such as it is, partly focuses on the Bush dynasty, and the opening scene shows George H. W. Bush, Barbara Bush, George W. Bush, and Jeb Bush playing a game of tennis. In this sense, the title of the play refers to the tennis court, but there is an entirely separate story explored in the actual court life of royalty. Sarah Ruhl is drawing parallels between the Bushes and royalty in 17th Century England and, though it doesn’t always work, the playwright certainly has a good time making observations about both time periods. In addition, most of the actors play more than one character and they all seem to be having a great deal of fun onstage.

T. Ryder Smith is just right as both George H. W. Bush (whom he resembles quite a bit) and Charles I. Matching him is Mary Schultz as Barbara Bush, with Angel Desai excelling as a crisp Laura Bush. Not to be outdone, Greg Keller is a marvelous George W. Bush and also a fine Charles II. Interestingly, the actor cast as Jeb Bush (the splendid Danny Wolohan) also plays a whipping boy in the 17th Century part of the show. It should be mentioned that scenic and costume designer Marina Draghici does a perfect job of supplying the cast with outfits that suit both eras, as well as being able to delineate clearly onstage which time period is being presented. This all sounds quite complicated, but director Mark Wing-Davey makes everything work and keeps “Scenes from Court Life” merrily spinning from beginning to end.

The playwright delights in her exploration of the Bush dynasty, poking fun at such moments when both George W. Bush and Jeb Bush were running for office in two different states, and she manages to embrace everything associated with the Bush family, from 9/11 to Jeb Bush’s failed attempt to run for president (and, yes, there is a Donald Trump character in the show). Similarly, the 17th Century royalty is equally presented in “Scenes from Court Life” and Sarah Ruhl makes that part of her play just as interesting. Not to give too much away, the playwright introduces such characters as the aforementioned whipping boy and even someone who is designated “groom of the stool” (whose duties are not to be revealed here).

“Scenes from Court Life,” overall, seems to be stronger in the first act, which runs about an hour, as opposed to the second act, which seems to trail on too long, almost as if Sarah Ruhl wasn’t quite sure how to end her play. Her fanciful world view (actually two worlds) is quite a lark, though, and her play is enjoyable even at the moments when the playwright is attempting to take on too much. It should be mentioned that all the actors are good in “Scenes from Court Life,” with an especially strong Keren Lugo playing both Catherine of Braganza and Columba Bush, and Jeff Biel and Andrew Weems do well portraying a multitude of roles.

Just based on the Yale Repertory Theatre production, “Scenes from Court Life” may need some pruning, but enough of the show is playful and intriguing enough to warrant a second look (and, hopefully, future stagings). Sarah Ruhl has done a fine job exploring two parallel universes and director Mark Wing Davey proves to be the ideal ally in giving “Scenes from Court Life” a topnotch staging. Add in a grand company of actors, and this show is definitely worth attending for a truly time-bending evening of theatre.

–

Connecticut Post-Chronicle – Tom Holehan – Bush Family Blasted in New Play at Yale. The Yale Repertory Theatre has opened its gala 50th anniversary season with the kind of play by a hot, contemporary author of which they are noted. This season’s world premiere is Sarah Ruhl’s ambitious, provocatively-titled “Scenes from Court Life, or the whipping boy and his prince”; a blistering satire about the George Bush political dynasty that probably won’t be happy news for Republicans. In this dreary election season, however, it seems something like a tonic.

Sarah Ruhl has had six of her plays produced at Yale thus far including “The Clean House” (2004), “Eurydice (2006) and the lovely “Dear Elizabeth” back in 2012. Her latest play is a bold and adventurous work which parallels the rise and fall of George H.W. Bush and his sons in American politics with that of Charles I and his son, Charles II in Stuart England. One set of actors portrays both family members in various stages of period costuming as the play progresses to the recent Republican primary where poor Jeb Bush is left in a puddle by then candidate Donald Trump.

“Scenes from Court Life” still seems like a work-in-progress as the play stalls and tends to repeat itself by act two and, hard as she may try, the parallels between the two time periods and families isn’t always apparent. Charles II’s “brother”, for instance, is the “whipping boy” of the title, not a blood relative at all and it seems a stretch by Ruhl to equate him with George and Jeb. The play can be dizzying with the numerous time shifts and its messy structure can get convoluted and over-stated. How refreshing it is, though, to sift through an overloaded original work like this, full of ideas and current commentary that is rich, funny and humane all at the same time.

Directed with deft precision by Mark Wing-Davey, the acting ensemble at Yale is nothing less than first-rate. As both Charles I and Bush 41, T. Ryder Smith preens like a prized peacock while both Danny Wolohan and Greg Keller excel as brothers Jeb and George (as well as their counterparts in England), mining every petty difference that lies between them to raucous effect. The playwright also manages to make room for some of the delicious malapropisms that made George 43 infamous. Mary Shultz is an earthy, sharp-tongued Barbara Bush and Angel Desai is beautifully restrained playing the mostly reactive role of Laura Bush. The ensemble breathlessly changes costumes and accents in what appears to be nanoseconds while the play careens and shifts like a runaway roller coaster with its incidental music and dance, supertitles hanging overhead and stage pictures that stun and delight.

In the cavernous University Stage space, Marina Draghici does wonders as both scenic and costume designer with strong support from Stephen Strawbridge’s lighting and Shane Rettig’s sound. Ms. Desai does double-duty as the play’s music director while Michael Raine creates individual choreography for both time periods. At the end, it may all be too much, but this inventive, timely satire still resonates as a new play very much worth seeing. 10.18.16

–

New Haven Independent, Donald Brown – In “Scenes Of Court Life,” There’s No Escaping History. In Shakespeare’s Hamlet, the prince’s advice to the players suggests that “the purpose of playing” is “to hold the mirror up to nature,” but we might wonder exactly what “nature” means there. Does it include political matters? Or something more essential?

Today, most of us — audiences, artists, critics — are aware that our “nature” is almost inextricably fused with our politics. Therein lies the purpose behind the arch and suggestive comedy of Sarah Ruhl’s Scenes from Court Life, or the whipping boy and his prince, now in its world premiere at Yale Repertory Theatre, directed by Mark Wing-Davey. The play closes this Saturday.

Scenes from Court Life aims to get behind the scenes of the lives of the rich and powerful. Ruhl creates a neat, though at times forced, paralleling of the English monarchy — specifically Charles I (T. Ryder Smith) and his son Charles II (Greg Keller) — with the “dynastic” aspects of the American family of George Herbert Walker Bush (Smith), which gave us, to date, a senator, a vice president who became a president, a governor who became a two-term president, and another governor. The parallel takes its best plot point from the fact that Charles I, who was executed, suffered Oliver Cromwell to take power from him and his heirs, while George H.W. Bush was unseated by the upstart Bill Clinton and prevented from a second term. Then, after the respective interregna, Charles II reinstated the Stuart line, and George W. Bush (Keller) served two terms, doing what his father couldn’t.

In the case of the Stuarts, there was no other son with a claim to the throne. In the Bush family, W.’s brother Jeb (Danny Wolohan) could continue the presidential dynasty — an idea that seemed more immediately plausible back when Ruhl’s play was first conceived. The Bush boys’ sibling rivalry is made a recurrent theme, beginning with W. announcing his run for governor of Texas at the same time as Jeb’s already planned run for the same office in Florida. But the more pointed parallel Ruhl chooses to exploit is between Prince Charles and his whipping boy (Wolohan), the servant who must endure the corporal punishment that, court etiquette dictates, cannot be visited upon the royal flesh. For purposes of parallel, poor beleaguered Jeb is his brother’s whipping boy. And indeed, Donald Trump (Jeff Biehl) shows up in the later proceedings — when Jeb is making his bid for the Republican nomination for president — to show that once a whipping boy, always a whipping boy.

Ruhl’s skill at theater-by-analogy keeps things moving nimbly for the most part. Both royals and Bushes like to play tennis, both like to engage in group dances — whether Texas square dance or baroque sarabandes — and Ruhl steers us to see less extrinsic parallels, such as Jeb’s wife Columba (Keren Lugo), born in Mexico, and Charles II’s whipping boy — Barnaby — wooing by proxy Catherine of Braganza (Lugo), a Portuguese princess. The latter storyline, as the main Stuart element of Act II, takes us a bit afield from the Bush business, which is where the play is strongest. Elsewhere comic elements stem from odd congruity. The monarch had a “Groom of the Stool” (Jeff Biehl), tasked with wiping the royal bottom. Meanwhile, W. called Karl Rove (Biehl), his senior advisor, “Turd Blossom.” The scenes playing on this give a whole new slant to the term bathroom humor.

Most of the cast plays a role in both the English court and the American family to considerable effect. In England, Keller and Wolohan play friends distanced by class and position who become blood brothers. In America, Keller and Wolohan play brothers distanced by ambition who are never quite friends. The best scene between the Bush brothers finds them grappling over toys as kids. For Ruhl, the childishness of these two men is never lost sight of, even when one is planning a military invasion and the other plays into Rove’s schemes for W.’s victory in the 2000 election.

The story of the actual prince and his actual whipping boy floats over the U.S. characters the veneer of court, while the Stuart scenes are complicated by their status as dress-up versions of the modern day scenes. At times the conflation produces great theatrical moments, as when Charles I suddenly removes his wig and becomes Bush I learning of his election night defeat, or when Charles II, in W. attire, suffers his own ass to be whipped rather than wiped, for a change. The most rewarding aspect of the play is when we see the prince peeking through W., and vice versa. At such times, Scenes of Court Life suggests a profundity in W. that he never enjoyed in reality.

But never fear, there are also scenes where the former president speaks about his painting with defenseless earnestness, and there’s a speech inspired by his gift for verbal gaffes.

As elder Bush and elder king, T. Ryder Smith is remarkable, playing both roles with studied dignity and subtle obtuseness that goes a long way to making the parallel work on stage. His is a wonderful portrait of the aging former president Bush. Greg Keller gets the walk and manner of W. spot on, though he makes his subject a bit whinier at times than suits W.’s public aw-shucks persona. Danny Wolohan’s Jeb never quite comes into his own, but his Barnaby gains stature as the play goes on, almost at his modern counterpart’s expense. Helpful support comes from Angel Desai as Laura Bush, who tends to break the fourth wall to take us into her confidence, as when she defends her husband’s actions on 9/11 and decries violence against America. Jeff Biehl’s Karl Rove and Groom of the Stool complement each other with a stoical sense of their place in the story.

In Act II the parallels become less rewarding and the two strands of the play begin to chafe somewhat against the forced correspondences. In the end, we’re given a swift conflation in a full-cast song that quips against empire — in which another country can always act as whipping boy for our sins — and beseeches us to rise up and vote. With a deliberately topical rather than satirical conclusion, Ruhl exhorts us that we still have a choice ahead that matters, even while reminding us of our past sins. Thoughtful, a bit precious, and a lot of fun to watch, Scenes of Court Life is anything but escapist theater. 10.19.16

–

ArtsFuse.org, Justin Sacramone – Sarah Ruhl’s “Court Life” – A Losing Match. As we storm to the conclusion of a political season in which the campaign motto for a major presidential candidates is pure nostalgia (“Make America Great Again”), historians, journalists, twitter yowlers, etc, are trying to figure out when (or if) we were ever all that great. American dramatists are putting in their two cents, with one of the most celebrated of our contemporary playwrights, Sarah Ruhl (via a commission from Yale Rep), picking through the entrails of American and British history in Scenes From Court Life or the whipping boy and his prince in a quest to figure out how our sense of who we were shapes who we are now.

Court Life takes a non-linear look at two political and royal dynasties at the apex and decline of their power: the Stuart family of 17th Century England and the Bush family of 20th and 21st Century America. The action begins on a tennis court (two-ton pun intended) as the Bush family discusses Jeb’s political aspirations to run for the governorship of Florida. George Sr. (T. Ryder Smith) and Barbara (Mary Shultz) are obviously smitten with Jeb (Danny Wolohan), who is personable, intelligent, and a far better candidate in their eyes than elder son George Jr. (Greg Keller), who is envious and desperately wants to make his father proud. In an effort to garner maximum attention he announces his intention to run for office at the same time as Jeb.

We are then tossed backwards in time and introduced to a young Charles II (also Greg Keller) and his whipping boy (also Danny Wolohan).The latter is among the poorest sods on the royal family’s payroll; his only job is to endure the beatings earned by Charles II’s misbehavior. Charles II has grown to like the whipping boy and is rooting for him to move up the ladder. Pinging and ponging back and forth between the two timelines (like a tennis match!) we get the idea Ruhl is telling us that Jeb is playing the whipping boy to George Jr.

The problem with Ruhl’s time-skipping experiment is obvious: Why are these two stories being intertwined? What, beyond the tiresome one-joke juxtaposition, is the disjointed narrative telling us of interest about the mentality of our ruling political junta? The harder Ruhl attempts to disclose (or force) similarities between the powerful then and now, the further away she gets from making substantial points, satiric or otherwise. In place of substance, Ruhl’s script is festooned with distractions; there’s excessive theatricality, such as a bloodbath execution scene, and musical episodes filled with singing and choreography.

Court Life would have worked if its lampooning had dig deeply into rotten foundations of the Bush family. Ruhl tries to explore how the Bush family turned itself into a political machine, but most of the scenes serve up stale anecdotes and cliches, settling for easy chuckles. Interesting possibilities are thrown away: a tense moment when President George W. Bush learns there are no weapons of mass destruction in Iraq would have been an opportunity to use the play’s device of parallel circumstances with the Stuart family to unpack how royals feel when they have been forsaken by the Divine. Instead, Ruhl chooses to skip the Stuart clan and give us George W. in a painting class where he learns the term “perspective.”

Fortunately, Ruhl’s script lacks vitality, but the Yale Rep’s cast and design team make up for the cartoon ennui considerably. The ensemble of eight principal actors are double and triple cast and portray a wide range of characters from both families. Familiar political archetypes are sent up in high, precise, and entertaining stylizations. The personalities of King Charles I and George Sr. are not all that charismatic, but there’s plenty of delight in watching how T. Ryder Smith portrays both characters differently and sometimes similarly.

Director Mark Wing-Davey transitions between the timelines well, but other elements of his staging are as heavy-handed as the script. The opening moment presents us with a traditional, regal dance setting, with Olde England making way for a rollicking hoe down. The ham-fisted culture shock is clear to the point of banality. Most writers playing with time — from H. G. Wells on — usually manage to be more surprising.

Marina Draghici’s set (she also did the costumes) takes place on a ‘real’ tennis court in act one; different worlds and eras impishly sit hidden behind doors on the upstage wall. In the second act the set evolves into an increasingly expressionistic playing space. Stephen Strawbridge’s lighting design enhances the feel of a gymnasium/tennis court with hanging fluorescent lights.

Philip Roth once memorably quipped that the outrageousness of American reality overwhelms the imagination of even our best writers. The intellectual thinness (Stoppard-lite?) of Court Life suggests that Ruhl is yet another victim of our homegrown buffoonery. 10.20.16

–

Curtain Up, David A. Rosenberg – And so the king sits on his throne. No, not that throne; the other one. Well, both really, at different times.

In the world premiere of Scenes From Court Life or the whipping boy and his prince at Yale Rep, Sarah Ruhl has written a funny, perceptive, scathing scatological screed that juxtaposes two dynasties — the Bushes of Connecticut, Maine and Texas with the Stuarts of England, Scotland and Ireland. Ruhl’s sympathies are obviously not with either tribe. Although separated by 350 years, both families are careless, calculating and contemptible.

It might have been subtler to write a contemporary comedy about George H. W. and George W., presidents 41 and 43, with their accommodating attendant Barbara and man-child second son, Jeb, the “whipping boy” to the princely George W. Or a history play about the Stuarts that more than hints at a contemporary parallel, with an historically accurate whipping boy, Jeb’s 17th century counterpart, Barnaby, who’s whipped whenever Prince Charles does something naughty. (Heaven forfend that the royal behind, though deserving, be beaten.)

Ruhl (author of the well regarded In the Next Room, Stage Kiss and Dear Elizabeth) doesn’t settle. Placing the Bushes in historical context by comparing their machinations with those of Charles I and his son, Charles II, allows for political results that are both frightening and hysterical.

True, such a scheme can descend into heavy-handedness, and does on occasion. And the evening seems over-long. Ruhl lays it on pretty thick, as in an extraneous scene where, in childhood, George and Jeb fight over toys.

There’s a lot going on here: Catholicism vs. Protestantism, love vs. justice, upper-class privilege vs. lower-class integrity. Ruhl, although privy to a rich trove of historical conflict, sets her pen to doling out Bush revelations. At one point, she has George W. repeat some of his foolish one-liners (“I know how hard it is for you to put food on your family”; “I know the human being and fish can coexist peacefully”; “It’s clearly a budget. It’s got a lot of numbers in it,” etc.)

Charles I, if you remember, lost his head, literally, paving the way for the disastrous Interregnum under the rule of Oliver Cromwell. Eleven years later, the monarchy was restored as Charles II became king. Although 41 does not face a similar fate as Charles I, he does wind up in a wheelchair.

Ruhl writes of Charles in rhyme, using the elevated language of the period. For the Bushes, the dialogue is modern and filled with vulgarities. Since both families are played by the same actors, British accents are required for the royals, American ones for the Washington crowd. Ruhl also cleverly juxtaposes tennis games, the one-upmanship contest the Bushes play vs. the more refined use in the Restoration reign of Charles II, when tennis courts were converted into theaters.

Director Mark Wing-Davey sorts out the permutations with skill and a welcome light touch. Michael Raine’s choreography wittily bridges the era gap, while Marina Draghici’s sets and costumes, Stephen Strawbridge’s lighting and Shane Rettig’s sound design cunningly contrast the play’s two eras.

In an excellent cast, T. Ryder Smith stands out as George H. W. and Charles I. Imperious but kind, a patrician not above grimy politics, his characters are complex and Smith fuses similarities and contradictions with the slightest gestures. Danny Wolohan is an awkward yet sympathetic Jeb, while Greg Keller is appropriately petulant, dumb and demanding as George W. and Charles II. As Laura Bush, Angel Desai is enigmatic, handling her big speech at the end of Act I with breakout sincerity. Her line,”Women bleed in private like animals; men bleed in public like kings,” sums up a play in which, among other themes, women stand by their men, putting up with their thirst for power.

But Ruhl’s true subject is how society and the individual interact, influencing one another. In”Scenes From Court Life,” she deals with the exigencies, the cruelties, the sacrifices, the rivalries that are both inevitable and poisonous.

[previous] [next]