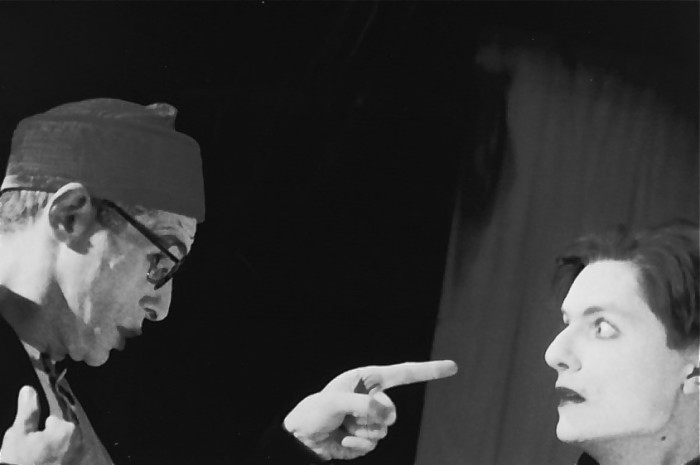

Above, top to bottom: Kenneth Talberth, Gretchen Krich, T. Ryder Smith, Joanna Adler, Mary Christopher, Barbara Weichmann; T. Ryder Smith, Joanna Adler, Mary Christopher, Barbara Weichmann; T. Ryder Smith, Mark Setlock; T. Ryder Smith, James Urbaniak.

Excerpts from the reviews

“A deliriously silly set-up . . . The troupers tear into their lines with great conviction, and a few of them are wonderfully right for their assignments . . . Best of all is T. Ryder Smith’s starry-eyed Dr. Baliardo. Whether poking his suspected moonmen for signs of earthly behavior, or becoming an unwitting go-between in intrigues designed to outwit him, Smith’s doctor is a fool worthy of Behn’s high-style foolishness . . . ” Jan Stuart, New York Newsday

“The play sweeps along a current of frustrated sexuality . . . Dr. Baliardo is duped into believing that the Emperor of the Moon and the Prince of Thunderland (actually the two suitors in disguise) have fallen in love with the young women whose honor he has been trying to safeguard. There are mistaken identities, false identities, fancied betrayals, injured feelings, multiple disguises, narrow escapes, and subterfuges and lies galore. . . . The standouts performers are . . . and T. Ryder Smith as the credulous father . . . ” Lawrence Van Gelder, New York Times

“A perfect vehicle for this highly professional group of players who have developed a style of their own . . . As Dr. Baliardo, T. Ryder Smith is truly unforgettable. Most of the time we laugh at this mad clown, but, finally, when he must give up his dream, and falls to his knees, his forehead touching the earth he will never leave, some members of the audience had tears in their eyes . . . “ Rosette Lamont, Stages magazine

“A fantastic and bracingly off-kilter take on this neglected comedy . . . The staging combines elements of commedia dell’arte, dance, doo-wop, and sign language . . . T. Ryder Smith . . . was among those outstanding in this company of luna-tics.” David Sheward, Backstage

Full reviews

New York Times, Lawrence van Gelder – Restoration Comedy From a Female Hand. The 17th and 20th centuries are coexisting agreeably these nights at the Ohio Theater on Wooster Street, where the theater company Arden Party is romping through Karin Coonrod’s staging of “The Emperor of the Moon.”

The ribald comedy is the work of Aphra Behn. History records her as the first Englishwoman to earn her living as as a professional writer. Behn turned to writing because her exploits as a secret agent for Britain during its war with the Netherlands from 1665 to 1667 went unrewarded. After a term in debtors’ prison, she competed successfully with other Restoration playwrights. She is buried in Westminster Abbey.

Behn’s popularity in her time is understandable. “The Emperor of the Moon” sweeps along on a current of frustrated sexuality involving two young cousins, their suitors, a credulous father and a pack of servants led by Scaramouch. The father is duped into believing that the Emperor of the Moon and the Prince of Thunderland (actually the two suitors in disguise) have fallen in love with the young women whose honor he has been trying to safeguard.

There are mistaken identities, false identities, fancied betrayals, injured feelings, multiple disguises, narrow escapes and subterfuges and lies galore.

So much for the 17th century.

The 20th century is present in the form of a black-clad female chorus (one member glides around on a single roller skate) that sings, comments on the action in speech and American Sign Language and referees the madcap proceedings with the aid of a silver whistle, hand signals and other gestures. The standout performers are James Urbaniak as Scaramouch, T. Ryder Smith as the credulous father and Joanna P. Adler, who utters not a word as a member of the chorus but is powerfully expressive. Their efforts give this farce plenty of flair. 1.23.95

Newsday, Jan Stuart – Moonmen And Their Women. Aphra Behn, born 1640, died 1689, was the first woman writer to bring home the bacon on the strength of her literary gifts. Erstwhile English spy and chum of poet laureate John Dryden, Behn is presently enjoying a resurgence in small part due to Virginia Woolf, whose classroom-lecture valentine to Behn echoed with renewed vigor in Eileen Atkins’ stunning 1992 presentation of “A Room of One’s Own.”

For all of that, Behn’s name is still a stranger to Webster’s Dictionary, while productions of her plays remain infrequent enough that there is the tendency to want to enshrine them like some collection of rare monarch butterflies. Don’t tell that to Arden Party, a feisty and seductive young theater troupe that is rapidly cementing a reputation for spanking the starch out of masterpieces. Who’s afraid of Aphra Behn? Not Arden Party.

This may not be the best news for “The Emperor of the Moon,” a delicious, late-career frolic that packed houses well into 19th Century. Taking off from an earlier commedia dell’arte play, Behn tweaked the repressions of Restoration Puritanism through Dr. Baliardio, a philosopher with a “Don Quixotic” fixation on the moon. Convinced that morally and intellectually superior beings reside there, the doctor conspires with his aide-de-camp Scaramouch to keep his daughter and niece away from Englishmen until he can find marriageable moonmen.

Scaramouch and the women have their own romantic agendas, however, and with a bit of artful finagling manage to convince the doctor that the ladies’ true loves are in fact lunar royalty. It’s a deliriously silly setup, but it manages to take some rather serious potshots at male sexual hypocrisy. These are women who know what they want (love with hot sex), go after it and get it, which is one of the reasons why Behn met with some of the same noisy defensiveness that makes many current prudes inclined to throw Madonna out with the bathwater.

From the defiant opening verse song to the sign-language epilogue, however, artistic director Karin Coonrod and her Arden Party seem more impressed with the author’s feminism than her skills as a farceur. A chorus of women, punked out in black gear, delivers a nose-thumbing rendition of a love chant, bumping and grinding through the quaint lyrics with teasing, contrapuntal audacity. Not a bad start: If nothing else, it fulfills all of our dormant fantasies about The Roches headlining in a Berlin cabaret deconstruction of “Lysistrata.”

Once the characters prance on in fussy platinum blond wigs, the huddle of women warriors turns into a three-woman peanut gallery, speaking all of the stage directions, hand signing some of the dialogue and providing the odd sound effect or responses to the actors. They’re never really funny, roller skates notwithstanding, and they never go away. The spoken stage directions, initially provocative, quickly become a cheap substitute for the pratfall or comic swordfight, adding to the air of freneticism as they siphon off the possibility for physicalized humor.

The ironic fallout is that a company that prides itself on its knockabout training leaves us the with impression that shtick is somehow beneath it. It’s a shame, because the troupers tear into their lines with great conviction, and a few of them are wonderfully right for their assignments: James Urbaniak’s lithe Scaramouch, Gretchen Critch and Paula Cole’s heavy-breathing Bellemante and Elaria, and, best of all, T. Ryder Smith’s starry-eyed Dr. Baliardio. Whether poking his suspected moonmen for signs of earthly behavior or becoming an unwitting go-between in intrigue designed to outwit him, Smith’s doctor is a fool worthy of Behn’s high-style foolishness. So is Darrel Maloney’s quick-changing design of receding red-and-black curtains. This “Emperor of the Moon,” however, is something less than lunatic. 1.12.95

Star Ledger, Newark, NJ, Michael Sommers – ‘Emperor of the Moon’ humors with light touch. Reputed to be the first woman ever to earn her living as a writer, the swashbuckling Aphra Behn (1640-89) is an especially fascinating figure from the Restoration period. A dynamic actress like Diana Rigg or Vanessa Redgrave should do a solo show about Behn, who whirled through her era like few other women before her. Back in the days when ladies were kept behind the scenes of influence, Behn was a popular playwright with 20 stage works to her credit, a ready poet and novelist, a political propagandist, even a British spy against the Dutch.

Jealous peers and sanctimonious scholars of later generations threw mudballs at Behn, accusing her of public indecency and personal immorality. But Behn’s doubtful and once-neglected reputation has been on the rise since the 1920s when Virginia Woolf observed, “All women together ought to let flowers fall upon the tomb of Aphra Behn, for it was she who earned them the right to speak their minds.” It’s a bit questionable, then, that director Karin Coonrod’s staging of Behn’s late comedy “The Emperor of the Moon” for the Arden Party theater company sometimes seems to verge upon a ventriloquist’s act, putting all sorts of extra inflections into the work that may or may not reflect the author’s intentions. Still, the new concept does not do too much injury to the play and Behn herself would probably appreciate the thoughtful and adventuresome spirit with which Coonrod tackles the piece.

First presented in 1687, “The Emperor of the Moon” is a romantic escapade as the daughter and niece of Dr. Baliardo gaily conspire with their lovers to outwit their guardian’s deluded authority over them. Aided by their double-dealing servants, the girls and their gallant beaux convince the moonstruck old scientist that those mysterious royal beings whom he believes to inhabit the moon wish to wed his charges. And so the show goes as the young people keep one foot ahead of the suspicious old boy. It’s a very light and frolicsome piece, a rare old looney tune of a comedy.

Deciding to give a serious feminist slant to the romance, the director has beribboned the play with an earnest new concept which adds a trio of black- clad women on the side of the stage who highlight certain words and stage directions in various voices and gestures. During the course of events, key moments are re-run and redone by the actors. Duels are stylized into posings. Though this is certainly an interesting approach from Coonrod, it “smells of the lamp,” as the old saying goes; it seems too studied a concept for such a freewheeling work, and it does not uncover any significant subtleties of message within Behn’s farcical text. Coonrod does not overwhelm the play with her approach, however, and Behn’s comic situations still offer some mirth.

This off-off-Broadway production is a handsome one to see, with a series of stylish maroon and black curtains gradually revealing the depth of the stage in Darrel Maloney’s smartly economical design, which he lights with poise. The director has also designed the costumes, which are colorful punked- out versions of 1680s attire in yellows, oranges and reds.

Among the 11 players, a limber James Urbaniak scurries about nicely as the servant Scaramouch who helps to hoodwink T. Ryder Smith’s interestingly not- so-foolish and therefore more formidable Dr. Baliardo, Paula Cole and Gretchen Krich portray the heavy-breathing young ladies in question, and Ledlie Borgerhoff is their laidback maid. The ensemble appears to romp through the show with genuine merriment, lending extra vibrance to Behn’s light charade. 1.18.95

[previous] [next]