Photos by The Hinge Collective and one by Jamey O’Quinn

Above, top to bottom: Lenore Pemberton and T. Ryder Smith; T. Ryder Smith and Steve Ratazzi; T. Ryder and Carol Vujcec; Lenore Pemberton, T. Ryder, Steve Ratazzi; same; Raphael Nash Thompson and Gretchen Krich; same; same; T. Ryder Smith and Nicole Halmas (photo by Jamey O’Quinn); Sue Jean Kim, Christy Meyer, and Purva Bedi.

Excerpts from the reviews

See full reviews below

“An adventurous production . . . Nothing is naturalistic. Everything but the work’s emotional substance is presented with a theatrical wink . . . The actors portray their characters instead of pretending to be them. They lug scenery, announce scene changes . . . Herskovits’ approach actually serves the play’s thematic through-line, which has to do with the peeling away of illusions surrounding love and work . . The casting heightens the production’s playful theatricality . . . T. Ryder Smith plays Trigorin as an insecure writer whose keen powers of observation can’t free him from his narcissistic bubble . . . Herskovits’ daring exurberance releases the play from the bog of realism into the realm of lyrical poetry.“ Charles McNulty, The Village Voice

“Herskovits [directs] to prevent audiences from surrendering romantically to the scripts’ emotional continuities. Taking his cue less from Brecht than from his own mentor Richard Foreman, Herskovits has said he ‘has no interest in reconciling a play’s many emotional moments, but rather in fulfilling each moment . . . maximally’. The result can be scattered and irritating . . . There are also invariably unique rewarding moments, however, and these are more numerous for me in ‘The Seagull’ . . . There are strong performances [including] T. Ryder Smith as Trigorin.“ Jonathan Kalb, The New York Press

“Konstantin, the author of the play-within-the-play in Chekov’s ‘The Seagull’, would probably be simpatico with an experimental Off-Off-Broaday theatre company like Target Margin. ‘We need new forms!’, after all, is the rallying cry of his artistic Russian soul . . . Herskovits tinkers adventurously with the text . . . the company’s tics do not spasm out of control . . . “ Peter Marks, The New York Times

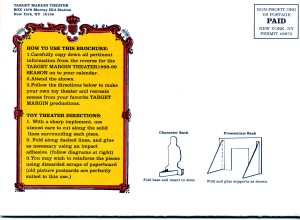

Publicity

Above, Beresford Bennett and Lenore Pemberton

Full reviews

New York Press, Jonathan Kalb – Michael Mayer is a hot commercial director these days . . . and I suspect his fear of the pit stymied him in ‘A Lion in Winter’. He leaves the impression that his head told him that this play needed an refreshingly aggressive concept, but his popular instincts ultimately amde him pull up short and choose a murky healf-measure. atching the production struggle for air, I wondered how an uncompromisingly avant-gardist like david herskovits (whose version of Chekov’s ‘The Seagull’ I’d seen the night before) might have handled Goldman’s play, which clearly needed either full deconstruction or full investment in its original stage dynamic. Whatever one thinks of Herskovits, one can’t fairly accuse him of pulling punches, and a calamity like ‘The Lion in Winter’ shows how difficult his sort of work is to do well. Herskovits has been doing downtown productions with his Target Margin for eight years, and the three classics I’ve seen him do before this (‘Titus Andronicus’, ‘Little Eyolf’ and “Measure for Measure’) have all been similarly directed to prevent audiences from surrendering to the script’s emotional continuities. Taking his cure less from Brecht than from his own mentor Richard Foreman, Herskovits has said that he has no interest in ‘reconciling’ a play’s may moments, but rather in ‘fulfilling each moment . . . maximally’, and the result can be extremely scattered and irritating. (the critic Marc Robinson called Target Margin’s “Measure for Measure’ ‘a “problem play” beset by slapstick problems’.) There also invariably uniquely rewarding moments, however, and these are more numerous for me in ‘The Seagull’ than they have been in the past. This has partly to do with the fact that ‘The Seagull’ is a play that asks penetrating questions about how artists think about the relationship between romantic and practical attachments, and the difference between real and spurious creativity. The set by Marsha Ginsberg consists of modestly non-descript wall-units, one bearing a raised section of cutaway floor, that are rolled into various awkward positions of the wide-open performance space, as if to keep the idea of form eclipsing function (the young writer Treplev harps on the need for ‘new forms’) perpetually before our eyes. The extremely heterogeneous cast – here, race-blind casting obviously fits Herskovits’ general aesthetic of of fragmentariness – is expectedly uneven, though a few performers cast against type open up interestingly novel views of their characters. The stout and bosomy Nicole Halmos, for instance, makes the egotism and miserliness of the aging actress Arkadina a question of literal entrapment in flesh, and Beresford bennett, a young black actor with a terrifically wrinkled brow, plays the most heartbreakingly baffled and spiritually vanquished Treplev I’ve seen. There are alsp more conventionally strong performances by Rafael Nash Thompson as Dorn and T. Ryder Smith as Trigorin. The show certainly has it’s puzzles (white dots on the actor’s foreheads, brief blackouts in the middle of speeches) and its annoyances. Herskovits has transformed the estae workman Yakov, for example, into a chorus of four stagehands all named Yakov who wear cool East Village clothes and punctuate the action with schticks whose dumb humor jangles with the intelligent humor behind so much else. Also, the famous writer Trigorin’s habit of interrupting intimate moments by jotting in a notebook has been transformed into a generalized and redundant index of self-consciousness, with the whole company writing on their hands with pens pulled from each other’s hair. This sort of jaggedness aside, though, what most sticks in mind from teh production is the ‘The Seagull’s questions about artistic seriousness and hard-work reflect on Herskovits, who – unlike the suicidally romantic avant-gardist Treplev – has gone about doing his courageously experimental work year after year, with the mature understanding that his perpetual dissatisfaction with himself is the key to making his next piece better. 3.24.99

New York Times, Peter Marks – Pick a ‘Seagull’ to Touch The Heart or the Head. Konstantin, author of the play-within-the-play in Chekhov’s ”Seagull,” would probably be simpatico with an experimental Off Off Broadway theater company like Target Margin. ”We need new forms!,” after all, is the rallying cry of his artistic Russian soul. His mother, the actress Madame Arkadina, on the other hand, would no doubt prefer the more conservative approach to the classics favored by the Pearl Theater Company. She is, of course, theater aristocracy, a practitioner from the old school. At the moment, there is a ”Seagull” in New York for each of them. Target Margin, under the direction of David Herskovits, and the Pearl, led by Shepard Sobel, are both staging productions of ”The Seagull,” Chekhov’s woebegone tale of betrayal, vanity and bitter decline among the members of a theatrical family and their hangers-on, that are illuminating reflections of disparate movements in downtown theater. The two variations on the play show off some of the brighter aspects (and also expose a few of the limitations) of what these companies try to accomplish; seeing them perform this play, one after the other, is a bit like being served the same nourishing meal twice, one cooked by Grandma, the other by your cousin with the nose ring. That two such divergent troupes would be drawn to this work is a testament to New York actors’ enduring attraction to Chekhov and, more specifically, to the tender, tragic relationship at the center of the play between Konstantin and Nina, the young idealists doomed to disappointment and despair. The poignancy of Nina’s plight — she’s the bright-eyed naif who falls in love with an older man and runs off to become an actress, only to be crushed by both the lover and the theater — is realized in both versions, thanks to the affecting portrayals by Margot White for the Pearl and Lenore Pemberton for Target Margin. But the essential difference between these two ”Seagulls” comes down to the dichotomy between the heart and the head. The Pearl’s traditionalist production, which continues in its theater in the East Village through March 28, tugs unabashedly at the heartstrings; it is, in fact, the most moving revival that I’ve come across in several recent encounters with the play in New York and in London. Within the framework of the set designer Beowulf Boritt’s elegant stand of birch trees on fabric, Mr. Sobel and his sentient cast home in splendidly on the manifestations of longing that permeate the play. In Christopher Moore’s love-starved Konstantin, in Joanne Camp’s desperately self-absorbed Arkadina, in Hope Chernov’s bleak and caustic Masha, one listens to the idle chatter but senses the oppressive weight of their stifled desires. Mr. Sobel’s staging, more completely than most other recent revivals, makes abundantly clear how profound is Konstantin’s torment at the miserly way in which Arkadina parcels out her love, and how this elemental alienation of affection sets the tone for virtually every other tangled relationship in the play. Mr. Herskovits’s production, running at the Ohio Theater in SoHo through March 20, tinkers more adventurously with the text, as is the practice of Target Margin, a troupe that seeks to infuse older plays with new essences. (Outlandish costumes, bizarre facial markings and weird sounds and lighting effects are among its standard tools.) In some previous cases, Mr. Herskovits has allowed his inventions to overwhelm his productions, but with ”The Seagull,” the company’s tics do not spasm out of control. The director plays wittily and continually with an audience’s sense of the way the world looks: the movable scenery, designed by Marsha Ginsberg, resembles flimsy movie flats, positioned at strange depths and angles in the Ohio’s loftlike space. (For the terribly sad final encounter between the spiritless Konstantin and the broken Nina, Mr. Herskovits moves the set forward, so that the actors practically play it in our laps.) Just as Chekhov sought to create vivid ensembles in three dimensions, Mr. Herskovits wants audiences to view the play from unorthodox perspectives, to appreciate these characters as more than emblems of Slavic society; a black Konstantin (Beresford Bennett) as the son of a white Arkadina (Nicole Halmos), obviously, does not immediately suggest the Russian countryside at the turn of the century. It’s the kind of hurdle Mr. Herskovits dares you to overcome, and when his actors are at their best — Ms. Pemberton’s Nina and Carolyn Vujcec’s Masha being the most accomplished — the play feels fresh, not obscured. (It must be noted, however, that the quality of the acting is not quite on a par with the that of the Pearl company, and the result is a performance that seems quite a bit longer.) Still, this small flock of ”Seagulls” provides playgoers with an excellent opportunity to compare, contrast and marvel at the familiar and surprising ways a classic takes flight. 3.13.99

Village Voice, Charles McNulty – “I can’t say I’m not enjoying writing it,” Chekhov wrote to his publisher in 1895 about The Seagull, “though I’m flagrantly disregarding the basic tenets of the stage. The comedy has three female roles, six male roles, four acts, a landscape (a view of a lake), much conversation about literature, little action, and five tons of love.” Constantine Treplev, the struggling avant-garde writer in The Seagull, flouts conventional dramaturgy perhaps even more than the playwright who created him. His over-the-top expressionistic play (incompletely presented in Chekhov’s first act) is partly a rebellion against the stilted 19th-century melodrama that has turned his mother, Arkadina, into a full-throttle diva both onstage and off. But Constantine is also in a desperate race to find his own distinctive voice, particularly since Nina, the object of his desire, has become enthralled with his mother’s lover, Trigorin, an eminent writer who fails to shatter the young actress’s overly romantic notions about the creative life. While remaining faithful to the essential spirit of The Seagull, Target Margin’s adventurous new production, directed by David Herskovits, pays little homage to traditional Stanislavskian realism. In fact, nothing is naturalistic— from Greco and Voyce’s humorously stylized costumes to Marsha Ginsberg’s jerry-built set-on-wheels, everything but the work’s emotional substance is presented with a theatrical wink. The action begins with the backstage preparations for both Treplev’s and Chekhov’s plays— the direction purposely blurs the distinction. Herskovits’s actors take a Brechtian approach in that they portray their characters rather than pretending to be them. They lug scenery, announce scene changes, and, in the last act, even serve as an onstage audience for the final encounter between Constantine and Nina. This may seem like heresy, but Herskovits’s approach actually serves the play’s thematic through-line, which has to do with the peeling away of illusions surrounding love and work— the deepest sources of existential meaning for Chekhov’s characters and, if you take Freud’s word for it, the rest of us as well. The nontraditional casting, which privileges Downtown ingenuity over seasoned training, heightens the production’s playful theatricality. Nicole Halmos, for example, would normally be considered both too young and too zaftig for the part of Arkadina, yet her delicious performance captures not only the comic trappings of her character but the misgivings and regrets buried underneath. Dressed in hip Soho finery, T. Ryder Smith plays Trigorin as an insecure writer whose keen powers of observation can’t free him from his narcissistic bubble. Lenore Pemberton, an African American actress who wouldn’t typically be cast in the role of Nina, is quite moving in her transformation from a naive girl to a grief- stricken woman who finds in her art not the glamour of her youthful dreams but a way to survive her cruel disillusionment. Beresford Bennett overdoes Treplev’s juvenile side, but he exercises noble restraint at the end. The sound of the door locking behind him before the fatal gunshot is devastating. Erika Warmbrunn’s new translation contains some disorienting anachronisms, though her version matches the respectfully whimsical attitude of the production. It would be easy to quibble with some of Herskovits’s more self- conscious directorial intrusions (such as the inexplicable blackouts and the stage manager’s bewildering call of “Curtain!” in the middle of scenes), but his daring exuberance releases the play from the bog of realism into a realm of lyrical poetry. 3.9.99

[previous] [next]