Photo by Carol Rosegg

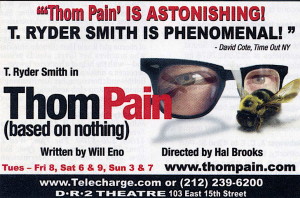

Excerpts from the reviews

Full reviews are below

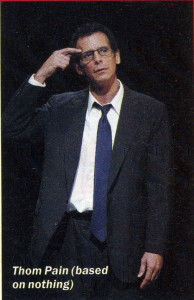

“As anyone who has seen a replacement cast can attest, producers will go to great lengths to find performers who look, sound and act just like the originals – or else they encourage replacements to mimic them precisely. It’s therefore a joy to report that director Hal Brooks has not tried to find an Urbaniak clone. T. Ryder Smith – a lean, dark-eyed smoky-voiced performer who could play a young Keith Richards – is phenomenal in the role, at times even outdoing his predecessor . . . He’s a perfect fit . . . Thom Pain may be a splendidly warped everyman, but not every man can play him.“ David Cote, TimeOut NY

“That audiences will stick it out for a little over an hour with this figure in the dark is testament to Eno’s captivating, enigmatic dramatic prose and T. Ryder Smith’s oddly bracing, broken charm and expert musicality as a performer. Smith’s darkly quirky, wry persona is both warmer and more mysterious than Urbaniak, who played (also brilliantly) a dry, chilly, irony-laden sad-sack. The drifting, elusive non-story of Thom Pain is now less stand-up than the shaky ruminations of a distraught abandoned lover . . . “ Caridad Svich, hotreview.org

Publicity

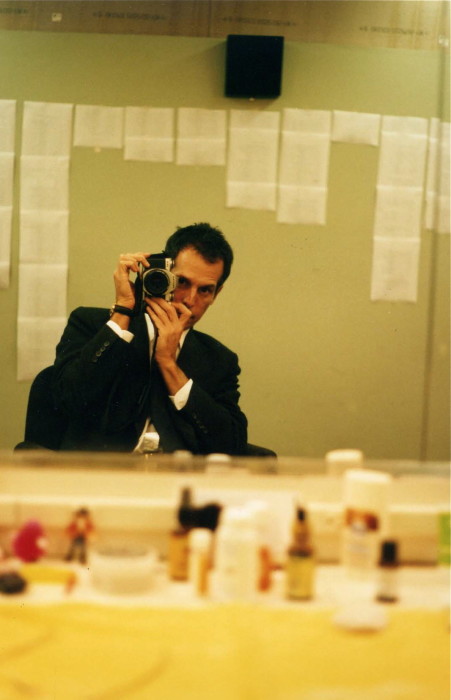

Offstage

Above: I had cut the script of the play into sections, to mark whenever the train of thought changed, and taped it to the walls of my dressing room. (It covered three.) I would walk slowly along the arrangement, reading through, before each performance.

Full reviews

Time Out New York, David Cote – James Urbaniak did more than just originate the title role in Will Eno’s wickedly mordant monodrama when it premiere earlier this year. through the sheer originality and weirdness of his autistic librarian schtick, Urbaniak wedded himself to the part. As anyone who has seen a replacement cast can attest, producers will go to great lengths to find performers ho look sound and act just like the originals or else they encourage replacements to mimic them precisely. It’s therfore a joy to report that director Hal Brooks has not tried to find an Urbaniak clone. T. Ryder Smith – a lean dark-eyed smoky-voiced performer who could play a young Keith Richards – is phenomenal in the role, at times even outdoing his predecessor in terms of emotional range. In recent years, Smith has brought his keen, vulpine intensity to works by Richard Foreman (The Gods Are Pounding My Head), David Greenspan (She Stoops to Comedy) and Anne Washburn (Apparition). As for holding a stage solo, Smith did that brilliantly in Glen Berger’s magic-realist monologue Underneath the Lintel in 2001. He’s a perfect fit for Thom Pain, a bleakly humorous antihero who dredges up grotesque painful memories, insults the audience, and wallows in masochistic self-loathing. Great credit, of course ,must go to Eno’s astonishing script, in which even the simplest phrase is spring-loaded with double-meanings, word-games and linguistic twists. Thom may be a splendidly warped Everyman, but not every man can play him. 9.29.2005

Hot.Review, Caridad Svich – Anatomy of Abandonment. Will Eno’s Thom Pain (based on nothing) opened in February 2005 at the DR2 Theater off of Union Square, starring downtown theater and indie film star James Urbaniak under Hal Brooks’s direction. In a theater scene that has lately been dominated by revivals, the lightest of upper-middle-class comedies, and a few Big Idea-laden history plays, Thom Pain is a resolutely ahistorical, deeply astringent and purposefully odd solo piece. It has nevertheless sustained an open run Off-Broadway at a time when the harsh economics of theater have forced many a promising show to close, and it has even weathered the precarious challenge of changing solo actors (T. Ryder Smith replaced James Urbaniak on September 5th). What is it about this deceptively slim text that has continued to defy critical description while garnering praise and attracting audiences?

Thom Pain opens with a figure in darkness. A cigarette is lit, put out and lit again. Stage light comes up in due course. Yet Thom will remain throughout the evening very much in the dark to us (and to himself), alternately inaccessible and transparent as air. Barely recovering from an intense love affair, Pain exhibits all the snarling, venomous badinage of a spurned lover, and all the painfully (pun intended) myopic isolation that comes from being deserted, cast off, and abandoned to the unclear whims of a chaotic, loveless universe. Pain, the insignificant schmo, is caught in a Sisyphean routine of wanting greatness in his life and knowing it can never be achieved, of wanting to tell a profound story but getting waylaid by distractions and minor details that only make him stop and not want to tell anymore.

“I disappeared in her and she, wondering where I went, left. It’s not clear what happened exactly. So you just try to…

Pause.

Do you like magic? I do. I think. It’s fairly ambivalent, this love of mine.

Pause.

Once a moth was flying around my room. I was afraid. A yucky flapping moth. And me. It all had some effect, I’m sure. Thank you very much. End of rumination.”

A fragment of a fragment, a self-described nobody, Pain is a figure easily ridiculed and by the same token, reviled. Similar to other classically ascetic American characters, like Melville’s Bartleby the Scrivener — characters that go against the ingrained U.S. archetypes of the Yankee/cowboy and the dandy — Pain is insular and contemptuous of others, a loner without the requisite high Romantic streak of yearning and melancholy. Pleasure is almost anathema to this nobody among nobodies, this loser slacker drifting through the ardent episodes of his bored little life. He is filled with rage, yet too self-aware to think it can be put to any good use. He is a comedian playing to an audience that he will never “kill,” in comic parlance. In the eternally (metaphorically) bare music-hall, Pain delivers his schtick (as Osborne’s Archie knowingly did in The Entertainer) to a laugh he will cut short with a verbal slap-in-the-face.

“He holds the handkerchief up.

Behold. Consider. Use your head and imagine this is a brain. Or, the mind. There it is, in the skull of a boy still in the womb, battleship gray and growing, folding over itself, turning, as he kicks his way into the world. … Such a feeling life, such sensation, yes? Then pile the words on top. And watch them seep down. Think of it. The brain and the mind. All that up there. Married, happily or not. Imagine.

Pause.

Or just think about snot. Imagine that this is a handkerchief. And that I just blew my nose into it.”

But surprisingly — and this is Eno’s sly brilliance as a writer — the hate-filled Pain begins to ingratiate himself just a little to his audience. His ambiguous relationship to the purity and miracle of life’s joys sparks through his vitriolic stand-up rant/sermon and catches even him by surprise. Moving slightly past the distress of being left by his lover, Pain does not entirely embrace life by play’s end. A wary trust, though, is won by his simply trying to sort out his non-story, and by offering it to others in the intimate, exposing confines of a theater.

“Maybe someone is waiting. Please be someone waiting. I’m done with this. Important things will happen, now. I promise. … I know this wasn’t much, but let it be enough. Do. Boo. Isn’t it great to be alive?”

It would be misleading, of course, to say that Thom Pain (based on nothing) is a cozy life-affirming treat, or that its passage from dark to darkish light is conventionally drawn. Eno is too sardonic a writer, too aware of life’s charade, to aim higher. In this sense, he is clearly in the post post-modernist line of novelists like Dave Eggers: a non-believing believer who wishes for something grand but cannot fully express it because grand schemes don’t amount to much anymore. It’s best to simply disappear in a climate riddled with fear: to be the non-musical “Mr. Cellophane.” However, Pain can’t stop trying, in spite of himself.

“Do me a favor. If you have a home, when you’re home, later, avoiding your family, staring at the dog, and they ask you where you’ve been, please just don’t say that you were out somewhere watching someone being clever, watching some smart-mouth nobody working himself into some dumb-ass frenzy. Please say instead…that you saw someone who was trying. I choose the word with care. I’m trying. A trying man. A feeling thing, in a wordy body. Poor Thom’s a-trying.”

Like Beckett’s Molloy, Thom Pain lives in a strange, mysterious world where the precision of language is the only tool left to describe life’s torment. It is apropos, then, that Eno’s voice as a writer, especially in this play, has connected with his audiences so strongly. In this piece, Pain is an unflattering reflection of the contemporary spirit: alone, almost virtual in appearance (barely there), alternately retreating and abrasive in manner, distrustful, riddled with fear, and aware that he is merely a toy in the machinations of a random, violent world. Effectively similar to the lead role in Mike Leigh’s classic 1990s film Naked, played to staggering, heartbreaking perfection by David Thewlis, Pain is a Hamlet bereft of a tragedy to contain him. There is no vengeance here, no kingdom to be won and no ghosts calling for remembrance: only loneliness and more loneliness, and stunted isolation. Whereas Leigh in his film charted an anatomy of the tragic in the contemporary individual (indeed, for Leigh, the depth and charge of classical tragedy is possible in the isolated urban landscape), Eno charts the anatomy of abandonment.

“Who am I, now, and what difference does it make? … She hurt me. I bled in the night. I hurt her. I wasn’t anywhere. Then I was in love. Now I’m here. … I did everything in fear. What was I so afraid of? I had promise. I don’t have anything anymore.”

Depth is hinted at but surface keeps claiming Pain, as surface and the simulation of the real, the mythic presence of reality, has captured many in the modern predicament. Post- Baudrillard’s theories, Pain is a figure virtualized and almost incapable of keeping a tangible object or storyline in view. The breakdown of breaking down is all this abandoned non-prophet can call his own. Eno pokes fun at the elemental state of his anti-hero, but also keeps trying to connect him to the natural world, the world he has abandoned, in effect, and from whose eco-system he has been cut off. The disembodied life that Pain lives, and that Eno posits many of us live, has stripped him/us of not only experience but also the ability to connect experiences and ideas to each other. Agonizing over his idealized lover, Pain, by virtue of who he is and the specifically Anglo-American, vaguely New England landscape from which he has been drawn, can only see microscopically. The bigger picture eludes him. The bite-size samples of his admittedly sorry little life are all he can barely hold onto. He is like an X-ray negative. And his sort of pain, which U.S. culture is addicted to in a media driven by tabloid tales of trauma and distress, is what we want more than anything. Even if it is “petty” pain.

That audiences will stick it out for a little over an hour with this figure in the dark is testament to Eno’s captivating, enigmatic dramatic prose and T. Ryder Smith’s oddly bracing, broken charm and expert musicality as a performer. Smith’s darkly quirky, wry persona is both warmer and more mysterious than Urbaniak, who played (also brilliantly) a dry, chilly, irony-laden sad-sack. The drifting, elusive non-story of Thom Pain is now less stand-up than the shaky ruminations of a distraught abandoned lover. Indeed, revisiting Eno’s remarkable play illuminates the love-hate relationship Pain has with himself and the world. Beneath a veil of anonymity, Pain questions civilization and the landscape in which humans pattern their lives. Alert to culture’s unending ambiguity, Pain refuses answers. It is our gain that Eno has invented such a misanthropic figure for our times.

New York Cool, Wendy R. Williams – Well, October was a particularly “dry” month for my theater attendance. I saw one play, the very clever Thom Pain (based on nothing), written by Will Eno and directed by Hal Brooks. Thom is a droll existential romp, a play that ruminates on everything and on nothing. And as stated in the title, it is based on nothing. There is a bare stage populated by one frumpy actor (the very talented T Ryder Smith) who delivered an hour and fifteen minute monologue about the everydayness of a life. Interspersed there was some wisdom about why we keep on going against both incredible and very boring odds. Every now and then, Mr. Ryder would interrupt his stream-of-consciousness musing to announce a drawing for a door prize or to request an audience volunteer. But he would soon drop that idea, losing interest in it before it had a chance to develop. And there you have it – Thom Pain, a droll night with a charming fellow. And that’s the best I can do to describe that. So, go see it and see if you can do better. P. S. It tends to sell out. The night I was there, it was packed.

[previous] [next]