Excerpts from the reviews

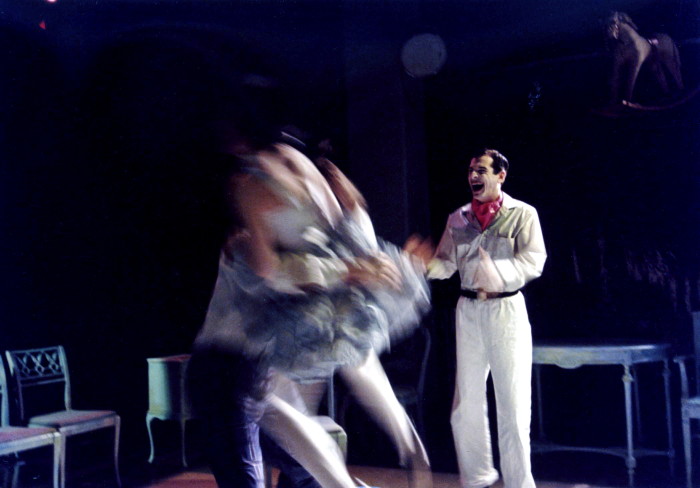

“Out of the mouths of babes come bombs in the implosive world of Roger Vitrac’s “Victor, or Children Take Over.” This seldom-seen 1928 French comedy, which has been given a smashing (in every sense of the word) revival by the Arden Party troupe, turns a 9-year-old’s birthday celebration into a riot of destruction in which that cute childish knack for speaking the unspoken has fatal consequences. You may have been taken to hell by kiddie parties yourself. But yours probably didn’t end with a major body count. Too real for the surrealists and too surreal for the realists, Vitrac had the misfortune to fall between intellectual stools during his lifetime. But this giddy, nasty little play (first directed by Antonin Artaud) now seems astonishingly prescient, anticipating the socially fracturing styles of Ionesco, Bunuel and Albee. . . . A compelling, visually arresting staging . . . [Gretchen Krich as Therese and T. Ryder Smith as Charles Paumelle] have a secret sexual relationship conducted with some of the strangest pillow talk in history . . . Director Coonrod uses ritualistic gestures, slow motion, time-splintering blackouts. But they always serve the play’s rhythmic counterpoint of what one character describes as “secrecy and lunacy.” And, for once, they do not turn the actors into automatons. Watch how Ms. Coonrod lets Mr. Smith and Ms. Harding rip fiercely into the juicy sexual confrontation of the play’s final act . . .” Ben Brantley, The New York Times

“If I were asked to select a favorite among the plays presented this season in New York, it would be this. This show is the ultimate romp. . . . [I saw] the 1962 revival directed by Jean Anouilh. His production was received as one of the events of the season but compared to this extravaganza it was a boring museum piece. . . [Arden Party] has developed a highly stylized form of acting which this writer had the chance to discover during . . . ‘The Emperor of the Moon’. It is partly derived from commedia dell’arte and employs elements of Asian theatre. . . the heavy white makeup on the actor’s faces, hands and necks [creates] a Pierrot-like mask, which slowly fades, revealing gradually the vulnerable, often ridiculous human beings hiding beneath the paint. “ Rosette C. Lamont, Theatre Week magazine

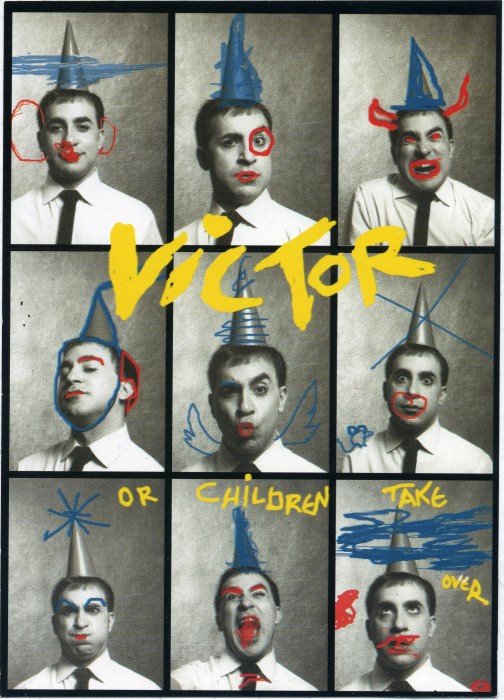

Publicity

Offstage

Front: Meredith Palin, Daniel Mason, Karin Coonrod, Steve Ratazzi, Randolph Curtis Rand.

Full reviews

New York Times, Ben Brantley – 9-Year-Old’s Master Plan For Disaster. Out of the mouths of babes come bombs in the implosive world of Roger Vitrac’s “Victor, or Children Take Over.” This seldom-seen 1928 French comedy, which has been given a smashing (in every sense of the word) revival by the Arden Party troupe, turns a 9-year-old’s birthday celebration into a riot of destruction in which that cute childish knack for speaking the unspoken has fatal consequences. You may have been taken to hell by kiddie parties yourself. But yours probably didn’t end with a major body count. Too real for the surrealists and too surreal for the realists, Vitrac had the misfortune to fall between intellectual stools during his lifetime. But this giddy, nasty little play (first directed by Antonin Artaud) now seems astonishingly prescient, anticipating the socially fracturing styles of Ionesco, Bunuel and Albee. “Victor” is pretty literal-minded by absurdist standards, but it also has an angry energy that is made for the theater. And Karin Coonrod’s intelligent, visually compelling staging taps into what adults find both frightening and exhilarating in children: a pure streak of anarchy that grown-ups spend most of their lives trying to repress. For Vitrac, Baudelaire’s artistic dictum about shocking the bourgeois obviously begins at home. “Victor” is set in the expensively appointed house of Charles and Emilie Paumelle (T. Ryder Smith and Jan Leslie Harding), a sea-foam green rectangle of chairs and sofas arranged with anal-retentive precision, while other items of furniture float ominously overhead. It is a world, in a set by Sarah Edkins, that exudes sickly stylishness, made to be dismantled. The architect of this process is the title character (the adult actor Steven Rattazzi), a boy consumed by mortal thoughts on his birthday. Though given to terrorizing the family maid (Mary Christopher) and breaking antique vases, Victor is more advanced nihilist than basic brat. “There are no more children,” he announces early on. Despite such observations (not to mention Victor’s penchant for erupting into worldly Dadaist rants), he and his playmate, Esther (the excellent Paula Cole, an adult who does childhood without the syrup), undermine social lies in ways familiar to any parent of precocious children. Victor knows just what questions to ask to send Esther’s unhinged father, Antoine (Patrick Morris), right over the edge. And when he and Esther perform a little play, based on a conversation the girl overheard between her mother (Gretchen Krich) and Charles, it unmasks a secret sexual relationship, conducted with some of the strangest pillow talk in erotic history. Also on hand are a doting family friend (Randolph Curtis Rand), and the enigmatic Ida Mortemart (Linda Donald), a lockjawed lady in an evening gown given to volcanic fits of flatulence. Ida, of course, is the spirit of the play incarnate. Ms. Coonrod, who will be directing the “Henry VI” plays for the New York Shakesepeare Festival, uses devices favored by deconstructionists like Anne Bogart and JoAnne Akalaitis — ritualistic gestures, slow motion, time-splintering blackouts. But they always serve the play’s rhythmic counterpoint of what one character describes as “secrecy and lunacy.” And, for once, they do not turn the actors into automatons. Watch how Ms. Coonrod lets Mr. Smith and Ms. Harding rip fiercely into the juicy sexual confrontation of the play’s final act. Ms. Harding, one of the great assets of New York experimental theater, is marvelous, as her character struggles vainly to turn disaster into cocktail-party chatter. (Just listen to the molasses-voiced variations she rings on the phrase “I’m controlling myself.”) Though Mr. Rattazzi is better at evoking the man within than the child without, all the actors find the pulse beneath their character’s grotesque postures. And everything seems tonally of a piece here: from the overripe, banality-warping language (the new translation is by Aaron Etra, Ms. Coonrod, Esther Sobin and Frederic Maurin) to Sonia Simon’s subversive take on haute bourgeois chic, with costumes that seem to work in references to every “ism” of early-20th-century art. Ms. Coonrod doesn’t always obscure the play’s more blatant manifesto elements, and one could do without such touches as pronouncing “terrible” in the French manner (presumably to underscore associations with Cocteau). But for a stylized director, working with an inordinately stylized piece, she is admirable for refusing to coast on the play’s surface. As a consequence, what could have been just a period curiosity takes on the recalictrant, prickly life of its underage hero. 4.8.96

[previous] [next]