Photos by Paul Kolnik.

Excerpts from the reviews

Full reviews are below

“I’ve seen plenty of Americans get soppy over animals in ways they never would over mere human beings. . . . The play speaks, cannily and brazenly, to that inner part of adults that cherishes childhood memories of a pet as one’s first — and possibly greatest — love. . . . Beautifully designed by Rae Smith (sets, costumes and drawings) and Paule Constable (lighting), this production is also steeped in boilerplate sentimentality. Beneath its exquisite visual surface, it keeps pushing buttons like a sales clerk in a notions shop. . . . The plot is your usual boy-meets-horse, boy-gets-horse, boy-loses-horse fare. . . . The characters are drawn in the broad strokes you associate with children’s literature, which limits the actors. . . . much of “War Horse” evaporates not long after it ends. But I would wager that for a good while, you’ll continue to see Joey in your dreams.” Ben Brantley, the New York Times

“A unique, remarkable experience . . . uses puppetry, music, and animation and projection design to help document the harrowing journeys of men and other animals during World War 1. . . . at once sweeping, unabashedly sentimental entertainment and a soul-wrenching testament to our species’ potential for brutality. . . . Robust folk songs and haunting visual images help capture the adrenaline of life during wartime, as well as its horrors. As the horses confront everything from barbed wire to machine guns, the puppeteers, through sound and movement, express their pain and fear, and their awe-inspiring dignity.We see war’s human toll as well . . . but we also see the capacity for courage and loyalty, humor and hope that keeps these characters going. . . . You’ll leave the theater emotionally spent but exhilarated.” Elysa Gardner, USA Today

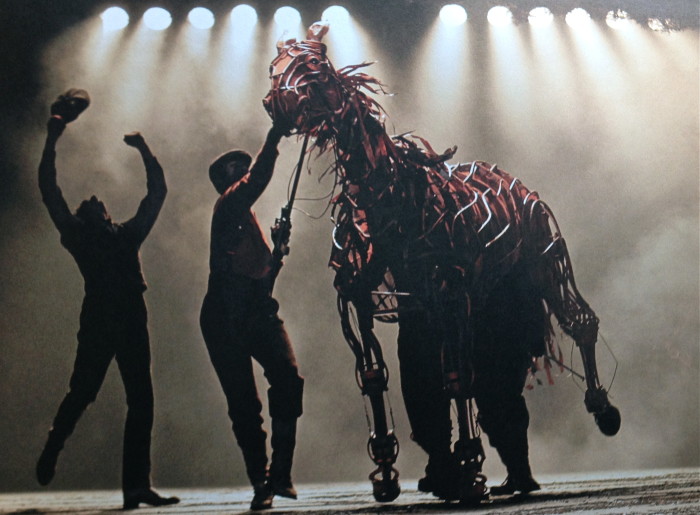

“The simple story, which, for all its ferocity, is not so much an anti-war play as a play about the false and brutal lessons that boys learn from their fathers (and the father figures who govern them), and must unlearn at their own peril. But the telling of this age-old tale is pure theatrical magic . . . The astonishing thing about all these life-sized horses — the beautiful beasts who go off to war and the emaciated creatures who collapse in the mud or emerge in tatters at the end — is the source of life that animates them. . . . Under the directorial hand of Toby Sedgwick, the horse-handling puppeteers (three to each horse) bring them to life through movement alone, in ways that are both dramatically dynamic and incredibly subtle. Topthorn is fearsome in battle, and from the very first moment we meet Joey he’s as warm-blooded and full of personality as any creature alive.” Marilyn Stasio, Variety

“Only sociopaths are impervious to the love between a boy and his dog—er, horse. So War Horse, the vividly staged, terribly told, dumbed-down, tear-jerking crowd pleaser at the Vivian Beaumont, is not a heartwarming triumph of human and animal spirits amid the barbarity of battle; it’s an exercise in indefensible manipulation, in which a boy longing to be reunited with the equine he adores is wrung for every possible tear: watch as they’re wrenched apart, while sad and soft violin music trickles through the speakers! As they endure the horrors of trench warfare while longing for each other’s unconditional love! By the end, there’s literally not one dry eye in the house; I, too, couldn’t stop sobbing. But I had not been made to cry. My tears had been stolen. . . . War Horse, ultimately, is vapid spectacle, its flashiness thinly concealing, and actually emphasizing, its simplemindedness and emotional emptiness. This is “family entertainment” at its most cynical. The show may not deserve your tears. But the injury it does to The Theater just might.” Henry Stewart, L magazine

Snapshots from technical rehearsals

Row 1: Stephen Plunkett; Jonathan David Martin holds a gate; T. Ryder Smith and Matt Doyle.

Row 2: horse Joey and T. Ryder; Jude Sandy and Ariel Heller with Topthorn and Joey; view from the balcony.

Row 3: Joey at rest: horse-fight; view from the stage.

Row 4: everyone tries to do a horse-call; T. Ryder and Peter Hermann; Young Joey training scene.

Row 5: Joby Earle takes a rest; costume chart note: “Germans are Always Dirty”; Ben Graney demonstrates.

Rehearsal snapshots

Row 1: rehearsal room; research wall; set model.

Row 2: beginning; February weather; Topthorn and Joey.

Row 3: Topthorn and Joey; puppeteers meeting; an acting exercise.

Row 4: horses in rehearsal; Topthorn; Joey up close.

Row 5: note session; puppet hospital; horse legs.

Row 6: set going up; Toby Sedgewick, movement coach; Cat Wallek.

Row 7: Boris McGiver and Alyssa Breshnahan; Zach Appleman; Madeleine Yeo, Peter Hermann, Cat Wallek.

Row 8: Ian Lassiter; Andre Bishop talks with cast; Seth Numrich and Stephen Plunkett rehearse.

Row 9: soldier puppets, tank being worked on in lobby; lesson in gun technique.

Row 10: Marianne Elliott gives a note; Adrian Kohler of Handspring Puppet company helps an actor with a wounded soldier puppet; Basil Jones of Handspring checks on one of the war horses.

Off-stage

Row 1: Billboard on Broadway; opening night wishes from other casts; our table at the Broadway flea market.

Row 2: Rick Steiger – our ace Stage Manager – with Joey; Toby Sedgewick imitates bacon frying during an acting exercise; dressing-roommate Stephen Plunkett and I wearing ourselves out.

Row 3: Stephen reading between scenes; Ian Lassiter at closing-night party; T. Ryder Smith, Stephen Plunkett, opening night.

Full reviews

New York Times, Ben Brantley – A Boy and His Steed, Far from Humane Society. It’s swoon time, ladies and gentlemen. Joey, the current marquee topper at the Vivian Beaumont Theater at Lincoln Center, is the kind of matinee idol New York hasn’t seen in ages. Tall, high-strung and handsome, with chestnut hair and eyes that catch the light, this strapping leading man is so charismatic you can imagine fans of both sexes lining up at the stage door with bouquets. Or maybe lumps of sugar and handfuls of hay.

One problem, though, with this fantasy. Once the curtain calls are done at “War Horse” — the imported British weepie that opened on Thursday night — Joey, its title character, ceases to exist until it’s showtime again. He is, it seems, one of those fabled stars of the stage who comes fully alive only when an audience is watching. Which, of course, makes him all the more captivating.

It takes a team of strong but sensitive puppeteers to bring Joey, a half-Thoroughbred who is sold into a World War I cavalry regiment, to life-size life. And it is how Joey is summoned into being, along with an assortment of other animals, that gives this production its ineffably theatrical magic. Steven Speilberg is working on a film version of “War Horse,” a 1982 novel for children by Michael Mopurgo. But nothing on screen could replicate the specific thrill of watching Joey take on substance and soul, out of disparate artificial parts, before our eyes.

This enchantment is the work of the designers Adrian Kohler and Basil Jones for the Handspring Puppet Company, based in Cape Town. And the spell cast has been strong enough to turn “War Horse,” which originated at the National Theater in London, into a runaway West End hit. A show that might otherwise have registered as only an agreeable children’s entertainment has been drawing repeat grown-up customers, who happily soak their handkerchiefs with wholesome tears.

Will Joey inspire the same success in New York? Of course we have heard about how otherwise stoical Britons fall into sobs at the sight of an imperiled steed or hound. But I’ve seen plenty of Americans get soppy over animals in ways they never would over mere human beings. I once attended a midnight show of Mr. Spielberg’s Jaws where the audience was heartily enjoying the carnage wrought by a man-eating shark until a pooch was seen swimming in the ocean, and someone seated near me, expressing the feelings of multitudes, called out, “Oh, God, not the dog!”

Directed by Marianne Elliott and Tom Morris, from Nick Stafford’s adaptation of Mr. Morpurgo’s book, “War Horse” taps that same keg of emotion. It’s “Oh, God, not the horse,” elicited to bring home the savagery of war. The play also speaks, cannily and brazenly, to that inner part of adults that cherishes childhood memories of a pet as one’s first — and possibly greatest — love. This is a show for people who revisit films like National Velvet and Old Yeller when they need a good cry.

In truth, the script of “War Horse” makes that of “National Velvet” (I mean, the heavenly 1944 movie, starring the 12-year-old Elizabeth Taylor seem like a marvel of delicacy. Beautifully designed by Rae Smith (sets, costumes and drawings) and Paule Constable (lighting), this production is also steeped in boilerplate sentimentality. Beneath its exquisite visual surface, it keeps pushing buttons like a sales clerk in a notions shop.

The plot is your usual boy-meets-horse, boy-gets-horse, boy-loses-horse fare. (To say whether boy gets horse again at the end would be telling.) The boy is Albert Narracott (a very good Seth Numrich), the son of a ne’er-do-well, liquor-loving Devon farmer (Boris McGiver) and a hard-working mum (Alyssa Bresnahan), who strives to keep peace between her menfolk. When Dad, drunk as usual, buys Joey at an auction — an act of sibling rivalry toward his hoity-toity brother (T. Ryder Smith) — young Albert takes on the animal’s care and feeding.

The early scenes of Albert taming Joey the colt and later teaching Joey the grown horse (they are two different puppets) to plow a furrow are nigh irresistible. (A charmingly fractious puppet goose also figures in the early scenes.) Joey is the platonic ideal of a stallion, with deeply expressive body language (his ears alone speak volumes) and no embarrassing habits like leaving piles of dung in his wake.

The show’s storybook sensibility is enhanced by projections of drawings by Ms. Smith on what looks like an outsize strip of torn paper, which fluidly convey shifts of time and setting. After Joey is sold by Albert’s father to a cavalry regiment bound for France, the production’s look segues from idyll to nightmare, with harrowing images of walking corpses, enveloping shadows and death-machine tanks and guns.

And of barbed wire, on which many a good horse met its end during World War I. (The show emphasizes how the use of horses in that conflict was a cruel anachronism.) Though human characters repeatedly bite the dust, it’s the horses on which our deeper hopes and fears are focused. (We meet several other war horses, including the fully defined, magnificent Topthorn, a seven-footer and Joey’s best friend, after Albert.) And it’s the visions of their being fatally tangled in wire that are the show’s most unsettling.

The show’s storybook sensibility is enhanced by projections of drawings by Ms. Smith on what looks like an outsize strip of torn paper, which fluidly convey shifts of time and setting. After Joey is sold by Albert’s father to a cavalry regiment bound for France, the production’s look segues from idyll to nightmare, with harrowing images of walking corpses, enveloping shadows and death-machine tanks and guns.

And of barbed wire, on which many a good horse met its end during World War I. (The show emphasizes how the use of horses in that conflict was a cruel anachronism.) Though human characters repeatedly bite the dust, it’s the horses on which our deeper hopes and fears are focused. (We meet several other war horses, including the fully defined, magnificent Topthorn, a seven-footer and Joey’s best friend, after Albert.) And it’s the visions of their being fatally tangled in wire that are the show’s most unsettling.

The human factor in the war-is-hell scenes (which feature a horse-loving German officer, played by Peter Hermann) is less convincingly drawn, incorporating clichés that have been staples of combat-theme films since the dawn of movies. Some of the melodramatic plot turns used here were old when David Belasco started out. And though the show has been trimmed and tightened since I saw it in London in 2009, at more than two and a half hours, it starts to feel ponderously long.

The characters are drawn in the broad strokes you associate with children’s literature, which limits the actors. Mr. Numrich achieves the transition from boyhood to manhood quite fetchingly, without violating Albert’s essential virginal nature. But it’s Joey and the mighty Topthorn who have the most complete personalities and who keep us watching as the plot plods on.

Every so often, a pair of balladeers (Kate Pfaffl and Liam Robinson) show up to sing about how we all “shall pass from this earth and its toiling” and be “only remembered for what we have done.” The implicit plea not to be forgotten applies not just to the villagers, soldiers and horses portrayed here, but also to theater, as an evanescent art that lives on only in audiences’ memories.

Judged by that standard, much of “War Horse” evaporates not long after it ends. But I would wager that for a good while, you’ll continue to see Joey in your dreams.

USA Today, Elysa Gardner – Puppetry, music bring War Horse to vivid life. If you’re wary of sobbing in public, or hold yourself above such maudlin behavior, you may want to bypass the new Lincoln Center Theater production of War Horse. But know this: You’ll be missing out on a unique, remarkable 4 stars out of 4 experience.Adapted from the Michael Mopurgo novel by playwright Nick Stafford and South Africa’s Handspring Puppet Company, War Horse uses puppetry, music, and animation and projection design to help document the harrowing journeys of men and other animals during World War 1.The result, which opened Thursday at Broadway’s Vivian Beaumont Theater after acclaimed runs at London’s National Theatre and on the West End, is at once sweeping, unabashedly sentimental entertainment and a soul-wrenching testament to our species’ potential for brutality.Even more fundamentally, though, it is a beautiful love story — about an English country lad, Albert, and his spirited, cherished horse. The latter, a half-Thoroughbred named Joey, is introduced as a foal but soon emerges as a mighty stallion — that is, a handsome representative made of cane, leather and wire, and given startlingly vivid life by a posse of actor/puppeteers.This creature endures a series of indignities — being caged in a pen, then auctioned off to Albert’s alcoholic father, who whips him — before the U.K. declares war on Germany. At that point, Joey is sold to the military, and a heartbroken Albert, though too young to enlist at 16, vows to find him on the battlefield.

The scenes that follow can be excruciating, as Joey and other horses, presented in similar fashion, discover human conflict at its most beastly. Robust folk songs and haunting visual images help capture the adrenaline of life during wartime, as well as its horrors. As the horses confront everything from barbed wire to machine guns, the puppeteers, through sound and movement, express their pain and fear, and their awe-inspiring dignity.We see war’s human toll as well — on Albert, who eventually lands in the infantry; on the young soldier he befriends there; on a German officer intent on protecting the horses.But we also see the capacity for courage and loyalty, humor and hope that keeps these characters going. The superb cast includes Peter Hermann as the sensitive German captain and Alyssa Bresnahan as Albert’s concerned mother.As Albert, Seth Numrich captures the indomitability of youth and the exuberance and despair that can accompany first love. Never mind that the other party in this relationship has four legs; try watching Joey nuzzle his teenage master without getting a lump in your throat. Little wonder that Steven Speilberg is bringing War Horse to the big screen in December — with real horses. But anyone who can should see this marvelous, life-affirming play first. You’ll leave the theater emotionally spent but exhilarated.

Variety, Marilyn Stasio – When it reaches the screen as a Steven Spielberg movie, “War Horse” will have real, live animals to represent the 8 million horses that were killed in World War I or sold to French butchers at the end. But no one who sees the National Theater of Great Britain’s haunting stage version of Michael Morpurgo’s children’s novel about a 16-year-old farmboy who follows his beloved horse into war will ever forget Joey — a puppet fabricated of wood and mesh and metal and manipulated by three human puppeteers, but so full of life you’d swear he had a soul.

Since this story was written for children, the plot is plain and the emotions are primal — the better to rip your heart out.

A sensitive boy named Albert (wonderfully delicate work from Seth Numrich) instantly bonds with the hunter colt that his father (Boris McGiver) impetuously buys at auction and cruelly turns into a dray horse. When this drunken lout later sells Joey to the British cavalry, Albert enlists in the infantry and goes to France, making his way from one battlefield to another in search of Joey, who survives through the working skills he acquired as a farm horse. Four years later, in the devastated wasteland of the Somme Valley, Albert finally finds Joey, no longer fit for hauling heavy weapons and human corpses, and about to be put to death.

That’s the simple story, which, for all its ferocity, is not so much an anti-war play as a play about the false and brutal lessons that boys learn from their fathers (and the father figures who govern them), and must unlearn at their own peril. But the telling of this age-old tale is pure theatrical magic in this story-theater-like production staged for an all-American company by Marianne Elliott (an associate director of the National) and Tom Morris (a.d. of Bristol Old Vic) and given its heart by the magnificent horsemanship of Adrian Kohler and Basil Jones, creative masterminds of the Handspring Puppet Company.

The vast stage of the Vivian Beaumont undergoes a terrible transformation (in the hands of scenic designer Rae Smith and the projection house of 59 Prods.) as the soft green hills of the English countryside give way to the blue-black skies and blood-soaked earth of the battlefields in France. (Paule Constable did the extraordinary lighting.) “Don’t show any fear or pity,” the officer riding Joey advises his cavalry when they arrive at the western front and encounter their first group of wounded soldiers and exhausted horses — puppets all.

But pity and fear are the only emotional options when Joey and his equine comrades, led by a majestic black stallion named Topthorn, obediently ride into this nightmarish landscape and begin falling to the modern weapons of barbed wire, automatic machine guns and tanks. With the exception of two bothersome folk singers wailing loudly about what we can plainly see, the hellish sounds of war (Christopher Shutt’s contribution) are articulate accompaniment to the savage battle scenes.

Some vestiges of humanity do survive in this dreadful place. The boyish exchanges between Albert and the young private (David Pegram) hunkered down with him in the trenches are sweet and sad. Even more compelling are the desperate efforts of the German field officer (played with exquisite feeling by Peter Hermann) to save Topthorn, the great war horse abandoned in battle.

The astonishing thing about all these life-sized horses — the beautiful beasts who go off to war and the emaciated creatures who collapse in the mud or emerge in tatters at the end — is the source of life that animates them. Amazingly, none of that vitality is reflected in their eyes, which are flat and inexpressive against the transparent fabrics that cover the sculptural complexity of their visible skeletons.

Under the directorial hand of Toby Sedgwick, the horse-handling puppeteers (three to each horse) bring them to life through movement alone, in ways that are both dramatically dynamic and incredibly subtle. Topthorn is fearsome in battle, and from the very first moment we meet Joey he’s as warm-blooded and full of personality as any creature alive. It’s a life that manifests itself in the tossing head, the heaving chest, the twitching ears, the quivering flanks — the very beat of his heart. His very big heart.

New York Post, Elizabeth Vincentelli – Vivid, powerful scenes stirrup emotion. A magnificent, exhilarating feat is taking place at Lincoln Center. Over the course of nearly three hours, the London import “War Horse” takes us to a farm in Devon, England, then to the killing fields of WWI. We marvel as life-size horse puppets gallop onstage — with actors riding them. We cringe in horror as troops charge and die under full-on shellings.

But if “War Horse” is theater as epic spectacle, it’s also theater as shared, intimate emotion.

Adapted from Michael Morpurgo’s 1982 children’s book, the show follows the shared journey of a 16-year-old farm lad, Albert (Seth Numrich), and his chestnut horse, Joey.

Brought together when Joey was a foal, the two are separated when the mount is sold to the British Cavalry and packed off to the French front. An inconsolable Albert enlists, hoping to retrieve his best friend.

What makes the show so powerful is the way the storytelling and the stagecraft are intricately melded. Directed with poetic ingenuity by Marianne Elliott and Tom Morris for the National Theatre of England, “War Horse” is full of breathtaking moments.

Though the horses don’t look realistic — their cane-and-gauze armature is visible, as are their handlers — they are lifelike, with twitching ears and heaving flanks, trembling in expectation, fear or agony.

This makes Joey’s ordeal all the more wrenching, because as soon as we meet him, we feel he’s as alive, as full of personality as any of the humans around him. And those are shown with an always kind eye — Peter Hermann plays a melancholy German officer who protects Joey and his war buddy, the black stallion Topthorn.

This is only one of the many empathetic bonds the show creates: not only among those onstage, but also between the characters and their audience. “War Horse” never talks down to its viewers, no matter how young they may be.

Some have branded the show as sentimental. Have we become so jaded that people are called suckers for crying during a good, old-fashioned tale? “War Horse” isn’t sentimental: It’s just not afraid to be emotional. Ultimately, the show succeeds because it tells children and reminds adults that some of life’s joys are made great by terrible hardships.

Scheck on Theatre, Frank Scheck – Stage wonders of the most magisterial sort are delivered in War Horse, the hit London production that has been remounted by the Lincoln Center Theater. This epic drama about the bond between a British boy and his horse combines dazzling stagecraft with deep emotion to create a simply magical evening that will enthrall younger and older audiences alike.

Adapted by Nick Stafford with the Handspring Puppet Company from Michael Morpurgo’ acclaimed novel, the show depicts the fateful adventures of Joey, the beloved horse of a farmer’s son, Albert (Seth Numrich), who winds up serving in the front lines during World War I. Joey was bought by young Albert’s father (Boris McGiver) when he was just a foal. When the animal proves ill suited for farm work, Albert’s mother (Alyssa Bresnahan) decrees that Albert raise him until he’s grown enough to recoup the hefty purchase price.

But when the war breaks out and the British army finds itself in desperate need of horses, Joey winds up serving for the British army despite Albert’s tearful protestations. Not long afterwards Albert himself volunteers and winds up fighting on the battlefields in France while attempting to find his beloved horse.

It’s a simple but powerful story, laced with generous doses of sentimentality. And the production–co-directed by Marianne Elliott and Tom Morris and which makes striking use of the vast Beaumont stage as well as the theater’s aisles–relates it magnificently. The primary distinguishing element is the fantastical puppetry created by Adrian Kohler and Basil Jones that is used to depict Joey and several other animal characters, including a fellow war horse, some rapacious vultures and a comically ornery goose.

The life-size horse creations, made out of plywood and fabric and which are each manipulated by teams of three actor/puppeteers, are remarkably vivid and expressive. Indeed, the illusion of living, breathing animals is utterly convincing, despite the fact that the puppeteers are often clearly visible.

The battle sequences are also particularly powerful, with evocative sound, lighting and projection effects employed that thoroughly draw us into the action. Such sequences as when the British officer is literally blown off his steed by a flying projectile and another in which Joey is confronted by a menacing tank are staged with a nightmarish intensity.

But the more intimate aspects of the story are hardly given short shrift, with the tender relationship between the boy and his horse conveyed in deeply touching fashion. The wonderful 35-person ensemble delivers deeply involving performances: Besides the aforementioned leads, there are standout turns by Stephen Plunkett as a kindhearted lieutenant; T. Ryder Smith as Joey’s uncle who is forced to send his own son off to war; and Peter Hermann as a German soldier who appropriates Joey after his regiment is captured.

Time magazine, Richard Zoglin – The first thing to marvel at in War Horse, the import from London that has just opened at Lincoln Center’s Vivian Beaumont Theater, is, of course, the horse. He’s a tall, chestnut-colored steed named Joey, embodied onstage by a life-size puppet manipulated by three fully visible puppeteers. A latticework of cane strips creates the effect of an exoskeleton, covering a leathery hide and forming a maze of gears and joints that animate the horse’s legs and neck. The result is amazingly lifelike and expressive: Joey rears, snorts, nuzzles, preens; his tail slaps at flies; his chest even heaves after a heavy workout. It’s all the product of South Africa’s Handspring Puppet Company — whose stage menagerie here also includes birds waved around on rods by actors and a nosy goose rolled across the stage on a wheelie. Has Julie Taymor seen this show? It might remind her of the low-tech wonders she created for The Lion King but largely abandoned for the high-tech daredevilry of Spider-Man.

The next thing that may strike a seasoned theatergoer about War Horse is how full the stage is. More than 30 actors! Portraying everything from a farming community in Devon to the battlefields of France in World War I. It’s the sort of epic theater that could only come from Britain, where state-supported institutions like the National Theatre (where War Horse originated) can really think big. Gathering more than five or six actors on a stage in New York City — at least for a show without stars, songs or a presold brand — is all but financially prohibitive.

But what’s most astonishing about War Horse — adapted by Nick Stafford from Michael Morpurgo’s 1982 young-adult novel and brought magnificently to the stage by co-directors Marianne Elliott and Tom Morris — is its sheer storytelling brio. It centers on a young Devon lad, Albert Narracott (Seth Numrich), whose father buys him a foal that Albert raises to be a hunting horse and that he then has to force to pull a farm plow; later, he loses him altogether to the army at the outbreak of World War I. The sprawling story covers a lot of ground in a tight space: there’s nuanced family drama (the plot spins off a rivalry between Albert’s father and uncle, the latter a Boer War hero, the former thought to be a shirker), lucid, large-scale military history, and a close-up picture of men in battle that rivals another World War I play, Journey’s End, in conveying the mundane horror of the so-called Great War.

The horse tale provides a vivid illustration of the startling reinvention of warfare taking place during World War I. The British send their proud cavalry onto a battlefield where machine guns and barbed wire render them tragically useless. The equine focus also serves as the vehicle for a familiar but still powerful message about the borderless tragedy of war: Joey winds up behind enemy lines and is adopted by a sympathetic German officer, who saves him from almost certain death by putting him to work pulling ambulance carts. Not least, it’s an emotional boy-meets-horse love story, as Albert, still only 16, enlists and gets himself sent to France to search for his beloved Joey. (No surprise that Steven Spielberg is turning War Horse into a movie.)

Part of the pleasure of War Horse is seeing the impossible-to-stage made plausible in the most economical and inventive ways: great battles evoked simply by a blinding flash of light, a roar of a cannon, or an interlude of slow motion or stop-action. And the cast is nearly perfect. (My highest praise is that I assumed I was seeing the British production transplanted to New York City; only later did I realize that it has been recast with American actors.) Is War Horse too sentimental? Perhaps. But there’s not a moment in its compact two and a half hours when I wasn’t fully engaged, moved and inspired by the theatrical imagination on display. And thrilled by a landmark theater event.

Entertainment Weekly, Tom Geier – Theater can be like magic. You can take an assemblage of wire, wood, and mesh — and convince people without a shred of doubt that it is a horse. And not just any horse, but Joey, the beloved half thoroughbred who is the heart and soul of the imaginative, moving new Broadway drama War Horse. First produced at the National Theatre of Great Britain in 2007, the play centers on a gawky British teen named Albert (Seth Numrich) who enlists during World War I hoping to find Joey after his drunken lout of a father (Boris McGiver) sells the steed to the British army. (Steven Spielberg’s film version is due in theaters this December.)

The play’s equine stars are the remarkable creation of Adrian Kohler and Basil Jones’ Handspring Puppet Company. As manipulated by three handlers dressed in period costumes, the life-size creatures seem to breathe, snort, feed, walk, gallop, and rear up just as naturally as the genuine articles. In no time at all, they become characters as rounded and complex as any of the humans on stage.

Perhaps more so, given that Nick Stafford’s script (based on Michael Morpurgo’s 1982 children’s novel) tends to assign the non-horse characters simple attributes and straightforward goals: Albert is a hardworking boy, his dad is an impulsive hothead, etc. They are two-dimensional archetypes, the stuff of kids’ theater — or of allegory. The final scenes build to a gut punch that underscores the particular horrors of WWI, which marked the last stand for cavalries since horses couldn’t compete with newfangled machine guns and tanks. The evocative message of War Horse lingers: Even as we seek to slaughter our foes with ever more ruthless efficiency, we need not lose our humanity

Newsday, Linda Winer – To describe “War Horse” as awesome is to regret the word’s devaluation as praise for a good burger or a pretty haircut. This extravaganza at the Lincoln Center Theater, based on a 1982 English children’s book by Michael Mopurgo is awe-inspiring both as a blast of pure theatrical imagination and as a deep gut-kick about lost innocence in war.

No matter what you may have heard about the horse puppetry in this recast smash from London’s National Theatre, the creatures created by the Handspring Puppet Company of South Africa are likely to feel more real — and more quietly eloquent — than a lot of people we think we know in plays.

Directed without an extra gesture by Marianne Elliott and Tom Morris, Nick Stafford’s adaptation tells the simple story of a poor country boy named Albert (beautifully played by Seth Numrich) whose beloved horse, Joey, is sold to the cavalry in World War 1. The boy lies about his age to enlist and, from 1914 to 1918, the two separately struggle through the intimate horror of the trenches and barbed wire to modern killing by machine-guns and tanks.

All this realistic horror — and real magic — is told with an exquisite minimum of scenery, little more than people power, a turntable and films projected on a ragged plank hanging above the semicircle stage. The effect combines the lean storytelling humanity of “Nicholas Nickleby” with some of the inventive animism admired in The Lion King. Each horse is made to breathe, to twitch, to appear to understand, by three people — two inside and one outside.

From the start, even the pastoral countryside is marred by the stupid vanity of people, including Albert’s well-meaning jealous drunk of a father (Boris McGiver) and preening uncle (T. Ryder Smith). And even in the worst parts of the war, universal kindness comes through in the disillusioned German (Peter Hermann).

If you love horses, the tearing-up may well begin with the first sight of Joey as a frisky, dark-eyed chestnut foal snuffling out his new world in the English countryside. But those who don’t weep for creatures also may be well advised to bring a hankie.

As the wandering peasant woman with the fiddle sings, we are “only remembered for what we have done.” The best of Broadway will be remembered for this one.

AM New York, Matt Windman – Michael Morpurgo’s 1982 novel “War Horse” is the kind of story that you never would imagine could be staged live.

Unlike Steven Spielberg’s forthcoming film version, which is set to debut later this year, using real horses on Broadway is not an option.

But thanks to a large cast and the most stunning use of puppetry since “The Lion King,” this co-production by Lincoln Center Theater and London’s National Theatre is absolutely masterful and immensely moving. It first premiered in London in 2007 and has been playing there ever since.

Set before and during World War I, the story follows the relationship between Albert, a young English farmboy, and his beloved horse Joey.

When Albert’s drunken father sells Joey to the army, the underage Albert enlists in order to find his horse in France.

Joey and several other horses are depicted onstage using life-size puppets that are each operated by three men. The puppeteers depict the horses galloping, breathing, screaming and interacting with human characters. The spectacle of the puppetry, however, serves the story and never overwhelms it.

The production is set on a bare stage aided by a series of line-sketch projections that emphasize the deadliness of war with graphic imagery. At the close of Act 1, Joey is seen jumping through patches of barbed wire amid machine-gun fire on the front lines. Toward the end, a giant tank even crosses the stage.

The large all-American cast is truly convincing and works seamlessly with the puppeteers.

Be warned that “War Horse” is a genuine tearjerker. But it is not so sentimental as to be off-putting. This is tug-at-your-heartstrings storytelling at its most spectacular and transcendent.

Wall Street Journal, Terry Teachout – Manipulated Puppets, Manipulated Tears. ‘War Horse’ was a big hit in London, and it will be a big hit at New York’s Lincoln Center Theater. It can’t fail, and it shouldn’t. Never again will you see such visually poetic, technically self-assured craftsmanship as is on near-continuous display in this large-cast stage version of Michael Morpurgo’s 1982 children’s novel about the adventures of a horse called Joey—played onstage by a life-size puppet—who is sold to the British cavalry in 1914 and shipped to France, where he is ridden into battle and lost behind enemy lines. Anyone who fails to respond to “War Horse” on the level of pure spectacle simply doesn’t like theater.

Unfortunately, there’s a catch, and it, too, is big: “War Horse” is the most shameless piece of tearjerking to hit Broadway since “The Sound of Music.” If that doesn’t stop you in your tracks, buy your tickets now. Otherwise, read on and be forewarned.

The synopsis of “War Horse” with which this review began is all you need to know about the events of the play, which is a straight-off-the-rack pageant of sibling rivalry, youthful rebellion, crazy courage and folk songs. Since critical etiquette forbids the revelation of surprises, even when they’re not surprising, suffice it to say that what happens thereafter is a cross between “Black Beauty” and “Saving Private Ryan.” Small wonder that Steven Spielberg is turning “War Horse” into a movie—only without the puppetry. That, however, will be like performing “La Bohème” without the music, since the puppetry is the point of the show. All of the animals in “War Horse” are “played” by puppets whose operators are visible to the audience, and it is this deliberate renunciation of conventional theatrical illusion that enables the poetry. You know that Joey and his fellow horses are mechanical dummies, but they are manipulated with such uncanny sensitivity that words like “realism” and “naturalism” quickly fade into irrelevance. They are, in truth, more “real” than flesh-and-blood horses could ever hope to be, for they engage our imaginations in a way that the real thing could never do.

No less imaginative—and poetic—is the way in which Marianne Elliott and Tom Morris, the directors, have joined forces with their design team to create a theatrical vision of trench warfare that crackles with the shock of recognition. When you “see” a soldier being blasted out of his saddle by a shell, or a horse dying before your astonished and horrified eyes, you’ll be reminded anew that the nonnaturalistic illusion of the stage can pack an emotional punch more powerful than the goriest of documentary photographs.

So . . . what’s not to like? The fundamental flaw of “War Horse” is that Nick Stafford, who wrote the script “in association” (that’s how the credit reads) with South Africa’s Handspring Puppet Company, has taken a book that was written for children and tried to give it the expressive weight of a play for adults. Not surprisingly, Mr. Morpurgo’s plot can’t stand the strain. Dramatic situations that work perfectly well in the context of the book play like Hollywood clichés onstage. In the first act, the craftsmanship is so exquisite that this doesn’t matter—much—but things go downhill fast after intermission. The really big problem is the last scene, about which, once again, the drama critics’ code commands silence. This much must be said, though: A play that is so forthright about the horrors of war owes its audience a more honest ending.

It also owes them better acting. Given the sterling track record of the National Theatre of Great Britain, where “War Horse” originated, it’s surprising that most of the performances of the speaking members of the cast are so one-dimensional. To be sure, that may well have more to do with the simplistic script than the abilities of the performers, as well as with the fact that the Lincoln Center Theater production of “War Horse” employs an all-American cast. (It’s not that Americans can’t act, but this is a very English show.) Whatever the reason, there is a wide gap between the expressivity of the puppets in “War Horse” and that of certain of their companion humans.

It’s worth pointing out that “War Horse” works both sides of the emotional street. The show’s portrayal of combat as a hell beyond imagining is a familiar exercise in the war-is-bad-for-children-and-other-living-things pacifism that is all but compulsory in the theater community. (You’ll wait a long, long time before you see a play on the New York stage that dares to suggest that some wars might possibly be necessary, even virtuous.) At the same time, though, the gooey sentimentality with which “War Horse” tells Joey’s tale undercuts the show’s implicit message, thus intensifying the slight but unmistakable whiff of phoniness given off by Mr. Stafford’s script.

This is, in all likelihood, a minority report: I have never heard more weeping in a theater than I did at the end of last Saturday afternoon’s matinée performance of “War Horse.” But even the easiest of weepers should beware of a show that pretends to be something it’s not, and “War Horse,” for all the glistening beauty of its craft, ends up being something not too far removed from a bait-and-switch con. If you’re looking for unsparing honesty, you’ll go home feeling used; if you bring the kids, they’ll have nightmares about the battle scenes. Either way, that’s a bad deal.

Hollywood Reporter, David Rooney – It’s easy to see what attracted Steven Spielberg to British children’s author Michael Morpugo’s novel “War Horse.”

But it’s hard to imagine how the screen version, due in December, can improve upon the thrilling experience of this stage adaptation, which is as emotionally stirring, visually arresting and compellingly told as anything on the filmmaker’s resume.

Produced by London’s National Theater, the play premiered in 2007 and went on after two sell-out engagements to become a smash in the West End, where it’s still running. This Broadway transfer makes tremendous use of the deep stage and various aisles of Lincoln Center’s Vivian Beaumont Theater, creating a spectacle both intimate and epic. The limited run is scheduled through June 26, but rapturous word of mouth seems certain to change that to an open-ended stay.

Adapted by Nick Stafford in association with the Handspring Puppet Company, the play is specific in its historic setting of World War I, yet any concerns about American audiences’ distance from that conflict are unfounded. The writer and creative team make this story universal in its reflections on war, its consideration of how we define courage and cowardice, and its portrayal of the purest kind of love.

Comparisons to “The Lion King” are inevitable but also facile. While the puppetry designs of South African company Handspring and its founders Adrian Kohler and Basil Jones are the undisputed stars here, this is an entirely different, far more emotionally immersive experience than the Disney show. It belongs to a rich tradition of British story-theater that favors artisanal craftsmanship over technology. When it works, as it does so exquisitely here, this can be as transporting for adults as it is for children.

Operated onstage by teams of three or more puppeteers, the life-size horses are breathtaking in their detail. The designs eschew naturalism for constructions of leather, cloth, cane and wire that share every secret of the mechanisms involved. Yet, in every way — their breathing, their flaring nostrils, twitching ears and soulful eyes, their powerful flanks and movements that can be skittish or graceful — these are not cute facsimiles but flesh-and-blood creatures. What’s remarkable is how quickly the puppeteers, who also provide vocal sounds for the horses, vanish through sheer force of imagination.

Directed by Marianne Elliott and Tom Morris with a fluid narrative grasp and seamless cohesion between design and performance elements, the show follows the life of a horse named Joey from birth. As a foal, Joey appears to grow before our eyes before being purchased by Ted Narracott (Boris McGiver), a Devon farmer. Ted pays a ridiculous amount for the horse merely to outbid his brother Arthur (T. Ryder Smith), their bitter rivalry shared by their respective sons, Albert (Seth Numrich) and Billy (Matt Doyle). When Ted’s feisty wife Rose (Alyssa Bresnahan) learns that the mortgage money has gone on a horse not even bred for farm work, she orders 16-year-old Albert to raise the animal until it’s healthy enough to fetch a good price.

Joey’s speed and strength attract Arthur’s attention, resulting in a bet with Ted that the horse cannot be trained to pull a plow. When Albert’s perseverance wins his father the bet, he also becomes Joey’s owner, nixing any plan to sell. But when Britain goes to war, and large sums are being paid for cavalry horses, Ted sells Joey to the army behind his son’s back.

Word reaches Albert that the officer riding Joey has been killed, so he runs off to France, lies about his age and enlists, determined to find the animal. Joey, meanwhile, has been captured by the Germans and put to work pulling an ambulance cart in a casualty clearance station in the Somme Valley.

The battle scenes are stylized, almost balletic at times, yet charged and visceral. The horror of horses being ridden into barbed wire and machine-gun fire yields particularly distressing moments. One striking stage picture, in which a horse and a tank rear up in each other’s paths, provides a wrenching illustration of the conflict of nature with the machine age. But despite its penetrating sorrows, the overriding tenderness of this story of how a boy and his horse endure the brutality of war will leave few in the audience unmoved.

One could nitpick that the directors overuse the folk songs and battle anthems that punctuate the action, or that Stafford’s writing is at times simplistic in explicating its themes, notably in a face-to-face encounter between a British and a German soldier. But overall, the presentation and writing are sentimental in the noblest possible way.

While the actors can’t quite compete with the majestic beauty of the puppets (which include ravens and an ornery goose), the American cast all contribute vivid characterizations and total commitment to the illusion that these animals are real.

Numrich brings heartbreaking conviction to Albert’s love of Joey and his almost unwavering faith that the horse has survived. In a uniformly strong ensemble, Peter Hermann also makes a deep impression as a German who assumes a medical officer’s identity to avoid returning to the front. This character typifies the play’s refusal to break down antagonists into villains and heroes, but rather to show that everyone is a victim in war.

It’s impossible to overstate the effectiveness of Rae Smith’s gorgeous design work. Its most evocative element is the torn page of a sketchbook overhead, which maps the shifting action and changing atmosphere with a mix of pencil drawings and projections.

In its blending of modern and traditional storytelling, its poetic imagery and primal emotion, this is the kind of magical theater event that comes along only rarely. As an introduction to the stage for young audiences, “War Horse” has the uplifting power to make lifelong converts. For more seasoned theatergoers, it has the elegance and inventiveness to erase the jaded memories of dozens of more cynical entertainments.

New York Daily News Joe Dziemianowicz – In a season flush with new plays and musicals, who would have figured that the odds-on favorite for being the most emotionally resonant story — at times overwhelmingly so — would be the one whose main character has four legs and is played by a puppet?

Broadway works in mysterious ways.

So does “War Horse.” This spellbinding show from London’s National Theatre runs full gallop with theatrical magic. It is by turns epic and intimate and compels you to hold your breath in anticipation. (Steven Speilberg’ sfilm version of the tale comes out in December.)

Based on Michael Mopurgo’s 1982 children’s book, which was told through an equine eye and voice,Nick Stafford’s stage adaptation loses any “Mr. Ed” qualities. People do all the talking, but the hero who gets the star bow is the horse Joey.

The plot spans about six years and follows his odyssey from hardscrabble but happy peacetime England, where he’s raised on a farm, to the enemy lines and brutality of World War I. Joey ends up on both sides of the gunfire and, finally, fighting for his life in a literal no-man’s land.

Melodramatic? Yes. Sentimental? Sure. And the characters and dialogue are etched in clean, if broad, strokes. But narrative thinness and contrived twists (there are some) are offset by the sheer scope of the production and the achievements of the South African puppet company Handspring.

The work by puppet designers Basil Jones and Adrian Kohler is exquisite. They bring Joey and Topthorn, a fellow war horse, and other animals so authentically to life you believe you’re seeing the real deal.

Three people operate each life-size horse. As they move the legs, rustle a tail, whinny and snort, puppeteers somehow fade from sight, even though they don’t try to hide.

Co-directors Marianne Elliott and Tom Morris also make no effort to sugarcoat the horrors of war; there are wrenching images of animals driven to near-death, and bodies of fallen men and horses littering the ground.

The duo oversees a physical production that shows care and attention at every turn. Rae Smith’s sets, costumes and homey line drawings capture a time, place and way of life.

Paule Constable’s jagged shards of lighting and Christopher Shutt’s eardrum-shaking soundscape put you in the middle of a battle zone.

The show’s fine ensemble is 35-strong. Seth Numrich, seen recently in “The Merchant of Venice” brings warmth and humanity to Albert, the young farm boy who raises Joey and risks his own life to bring him home from war. Peter Hermann, known from “Law & Order: SVU,” does fine work as a compassionate German soldier and family man who ends up holding Joey’s fate. Kate Pfaffl impresses with a rich and haunting singing voice. She punctuates scenes with simple but stirring folk songs.

“War Horse” is rooted in children’s literature, but its themes of love, war and the life-sustaining bond between people and animals speaks to audiences of every age.

What it has to say, it does so onstage with enormous power and imagination.

Vulture.com, Scott Brown – The Fog of War Horse. There are many wonders in the Brit import War Horse — the most intense and epic children’s entertainment ever mounted on Broadway, and certainly the greatest achievement in large-scale mainstream puppetry since The Lion King — but none of them can compete with the show’s opening. We meet a horse. He canters, he swats flies with his tail, he flicks his ears at the slightest sound. He breathes. He’s made of cane and silk and leather (by South Africa’s miraculous Handspring Puppet Company, in collaboration with the National Theatre of Great Britain), and operated by a team of people who quickly melt into horseflesh and are forgotten. (Until the curtain call, when they are justly adored.) This horse is alert and alive — so much so, we realize only slowly that the script he’s dragging is neither.

For out of this herbivore Eden, a ghostly chorus emerges, singing a soul-tugging old hymn (Bonar and Tams’s “Only Remembered”) about suffering, glory, and immortality, three things a horse has no goddamned use for. The foal starts, sensing danger — as do we. Because this, alas, is the last grown-up moment of the evening: Once the vile bipeds start chattering, they don’t stop for two hours, no matter how much we mentally plead. The source novel by Michael Morpurgo is told from the horse’s perspective; the decision to stray from that model I find disappointing. There’s not a single beat of this show that wouldn’t have benefited from wordlessness: Its mute animal energies are far stronger than its wooden text, its simulated beasts far more expressive than their thinly written, bathos-soaked riders, who are, to a man, mouthpieces and messengers, simple mechanisms of plot contingency. The acting style, by necessity, is relentlessly indicative, the dialogue pure Passion Play.

But then, War Horse — the story of a poor farm boy (Seth Numrich) and his beloved mount, Joey, parted by the Great War, searching each other out through a vast no-man’s land mined with cliché and spring-musical accents — is not really designed for adult minds. (Be warned, parents: The British equivalent of children’s entertainment isn’t as shy about carnage and defeat as our comparatively triumphal American version. World War I occupies a very different mythic niche “over there.”) Even the sick joke of cavalry charges in the face of machine-gun fire, one of history’s more disgusting collision points, is absorbed into the show’s standard-issue war-is-bad pacifism (a message blunted — spoiler alert — by the ultimate victory of Providence, at least for our main characters). The ravishing, nightmarish backdrops — horses dragging infernal weaponry through sloughs of mud and blood, demonic tanks emerging from the pit, hurricanes of barbed wire sweeping in from the wings — all but swallow the characters, and I, for one, wish the play’s creators had simply given in to this, and allowed their stock stick figures ( the “good German,” the noble soldier, the cruel soldier, the innocent child) to recede, or at least shut up.

I’ve heard many people comment that, within minutes, they forgot Joey was a puppet: They saw a real horse. I did, too, but with an unfortunate corollary sensation. The more horselike the puppet became, the more puppetlike I found the human actors. Maybe that’s what we look like to a horse?

The New Yorker, Hilton Als – Like “Gone with the Wind,” “War Horse” (a National Theatre of Great Britain and Lincoln Center co-production, at the Vivian Beaumont) is virtually critic-proof. The show—an epic tale of a boy and his horse, based on Michael Morpurgo’s 1982 children’s book, and performed by humans and puppets—is beyond dramaturgy, and it’s too big and emotional for anything as small as opinion. It’s a force of nature, or, more accurately, a show about the nature of man, which the co-directors, Marianne Elliott and Tom Morris, shape with the utmost control and artistry. Everything about it works, especially the animals—horses, birds, even a goose—which were created by the Handspring Puppet Company. (Actors manipulate the puppets to convey the animals’ souls.) In a way, the ambitious choreography of the piece—there are thirty-five actors in the cast—makes “War Horse” as much a dance work as a theatre piece. I don’t know who wins here, Thespis or Terpsichore, but why choose?

Set in southwestern England and in France before, during, and after the First World War, “War Horse” follows the story of a poor English boy named Albert Narcott (the charming Seth Numrich), who falls in love with the only being who seems to love him unconditionally: his horse, Joey. As Joey grows from a foal into a horse, Albert grows from a wide-eyed innocent into a strong and brave soldier. The show starts off in the realm of Enid Bagnold, but at the end of the first act the directors move us from a landscape of thatched roofs and cardigans to a world of death and cruelty that’s more reminiscent of Pat Barker’s gripping and horrifying trilogy of novels set during the First World War. Yet, even in this blighted wasteland, redemption is possible. After many chills and spills, Albert and Joey come together again. Beneath “War Horse” ’s gray, smoky realism, the essential narrative is one of hope.

L Magazine, Henry Stewart – Only sociopaths are impervious to the love between a boy and his dog—er, horse. So War Horse, the vividly staged, terribly told, dumbed-down, tear-jerking crowd pleaser at the Vivian Beaumont, is not a heartwarming triumph of human and animal spirits amid the barbarity of battle; it’s an exercise in indefensible manipulation, in which a boy longing to be reunited with the equine he adores is wrung for every possible tear: watch as they’re wrenched apart, while sad and soft violin music trickles through the speakers! As they endure the horrors of trench warfare while longing for each other’s unconditional love! By the end, there’s literally not one dry eye in the house; I, too, couldn’t stop sobbing. But I had not been made to cry. My tears had been stolen.

Exploiting the relationship between animals and people, especially children—that is, taking advantage of what Ben Brantley called “that inner part of adults that cherishes childhood memories of a pet as one’s first—and possibly greatest—love”—is the cheapest narrative device an artist can employ, and War Horse plies it with expertise. After all, it’s the only trick in its bag; its capacity for pandering sentimentality is endless. Set in England before WWI (and France during it), the play, based on Michael Morpurgo’s children’s novel, revolves around Albert (an overeager Seth Numrich) and the best-friendship he forges with a foal in a Devonshire populated by rural, post-Victorian clichés—a mean rich uncle (T. Ryder Smith), a no-good boozy pop (Boris McGiver), a willful, persevering mum (Alyssa Bresnahan), and so on. When The War comes, Albert’s sodding father sells the now-grown horse to the army, and shortly thereafter the 16-year-old enlists to search the war-scarred French countryside for his only friend. (In the trenches, adolescent Albert’s horse obsession borders on the morbid; shouldn’t he be thinking about girls like all the other soldiers? Was Daniel Radcliffe originally approached for the part?)

The English’s naïve jingoism on war’s eve is belied by the realities of modern, ungentlemanly conflict. Turns out that combat is no fun and holds no glory, just cruelly indifferent violence. Who’d-a thought? Act I’s halcyon farm days give way to Act II’s far grimmer war scenes, where the terror and brutality are both plain (charred, hobbling survivors toting corpses) and expressionistic (blinding bursts of light and giant bullets carried on long poles). Many horses die: from exhaustion, from mercy killings, from getting caught in barbed wire. The playbill notes that eight million horses met their ends during the Great War; for every 16 horses that the English took to France, only one returned. Lest this grimness make you feel too bummed, though, the play also introduces a little French girl, whose persistent and unbearable cuteness is meant as reprieve. There’s also a mean German whose description of horses as “just beasts!” invites your seething jeers. And, SPOILER, your favorite horse survives.

How about that horse? The characters might be flat, but the horses are awesome—creaking, expressive, stunning puppets, each of which require three manipulators whose harmonizing sound effects create the animals’ sounds. The puppets trot, heave, and graze; they stomp, whinny, and huff their tails, seeming more real than real horses (or, god forbid, those given the gift of voice by CGI) despite their conspicuous fabrication. They’re the most emotionally sincere things on the stage—more than the mugging actors, the caricatural characters, or the calculating heartstrings-tugger calling itself a script. But even that magnificence works against the show. War Horse, ultimately, is vapid spectacle, its flashiness thinly concealing, and actually emphasizing, its simplemindedness and emotional emptiness. This is “family entertainment” at its most cynical. The show may not deserve your tears. But the injury it does to The Theater just might.

Backstage, Erik Haagensen – I’ve never been keen on horses, and puppets in the theater tend to arch my eyebrows. Nevertheless, from the moment the life-size puppet of a foal loped lazily onto the vast Vivian Beaumont Theater stage as two birds, attached to long poles in human hands, were wheeled across the heavens, I was hooked. For two and a half hours I sat enthralled by “War Horse,” taken completely out of myself and the petty concerns of my life. Gloriously theatrical and almost unbearably moving, this stirring testimonial to the power of honest sentiment is a never-to-be-forgotten theatrical experience.

The time-honored tale of a boy and his horse, the play is set during World War I. Albert Narracott is a farm kid from Devon, England, whose drunken father, Ted, buys a foal with the mortgage money. Albert’s furious mother, Rose, charges her son with the responsibility of raising Joey, as the boy names him, to adulthood, when hopefully the proud riding horse, unsuitable for farm work, will fetch a good price and repay the crushing debt. Of course, Albert and Joey develop a special bond, but when war intervenes, Ted sells Joey to the army. The underage Albert runs away to enlist and search for his soul mate. The rest of the plot details the experiences of boy and horse on the battlefields of France.

Directors Marianne Elliott and Tom Morris marshal their forces with limitless invention. Rae Smith’s inspired piecemeal set is dominated by a great curved slash of what looks like parchment, on which drawings (by Smith) and videos are projected. (What it turns out to represent is one of the evening’s greatest pleasures.) Paule Constable’s chameleonic lights evoke everything from a pastoral English morning to the stark horrors of warfare. Adrian Sutton’s dramatic musical score and John Tams’ songs are indispensible. The astonishing puppets, created by Adrian Kohler with Basil Jones, range from those extraordinary horses to geese, vultures, and even a tank. But none of this immense creativity would have the desired effect without the script and performances to realize it.

Fortunately, Nick Stafford’s canny adaptation of Michael Morpurgo’s fine children’s novel is top-drawer. It wasn’t an easy task, because the novel is told in first person—from Joey’s point of view. As Joey doesn’t speak here, Stafford has very intelligently kept the story’s bones while beefing up the cast of humans in thematically reinforcing ways and replacing a novelistic structure with a dramatic one. His reinvention of the climactic reuniting of Joey and Albert is a particular triumph

I haven’t the space to single out all the excellent work done by the 35-person American cast. The first nod must go to the amazing puppeteers who embody Joey (Stephen James Anthony, David Pegram, and Leenya Rideout are the foal; Jeslyn Kelly, Jonathan David Martin, and Prentice Onayemi are the grown horse) and Topthorn, another majestic English horse (Joel Reuben Ganz, Tom Lee, and Jonathan Christopher MacMillan). They create thoroughly detailed personalities solely through sounds and movement. Among the speaking actors, Peter Hermann contributes a vital turn as a sensitive German officer longing for his family, Stephen Plunkett makes a forceful impression as his sketch-artist English counterpart, Alyssa Bresnahan is a fiercely loving Rose, and Madeleine Rose Yen is a force of nature as a young French girl who cares for Joey.

Ultimately, however, the show belongs to Seth Numrich as Albert. The Juilliard-trained actor, whom I first admired Off-Broadway in 2009’s “Slipping,” is the heart and soul of “War Horse.” His vivid performance is rigorously honest, with a breathtaking emotional transparency. Commanding the stage like a seasoned vet, Numrich effortlessly provides the considerable size that this production requires. I only hope that his superb work will be recognized come awards season.

Woman Around Town blog, Michall Jeffers – Deep into the second act of War Horse, a woman sitting a few seats away from me sobbed hysterically and cried out “No!” during a climactic scene. I got the distinct impression that she was more involved in the drama inside her head than in the play on the stage.

I guess you’re either there or you’re not, and I wasn’t. War Horse is a potent theatrical event, unique, captivating, beautifully realized. The plot is basically boy gets horse, boy loses horse, boy gets horse back. Spoiler alert: Geez, lady, after two and half hours of watching this heart wrencher unfold, did you really think they were gonna shoot the horse and risk having everyone leave mad?

As almost all theater goers probably know by now, the horses are portrayed by actors serving as puppet masters from both inside and outside the animal being portrayed. The ear twitching, chest heaving, and hoof stomping movements are perfect. High praise goes not only to the performers, but also to Toby Sedgwick, who is listed in the Playbill as “Director of Movement and Horse Sequences.” We truly do get a sense of the equine persona for each horse.

War Horse is a National Theatre of Great Britain production, which features an all American cast. This probably explains the inconsistency in the accents, which occasionally veer into brogues. The music, which sounds quintessentially rural British, includes some lovely songs and singing, violin, and accordion. It’s highly evocative, and in the Second Act, under used.

Set in England just before, during, and after WWI, the play revolves around the attachment that young Albert Narracott (Seth Numrich) forms with his horse, Joey. I was unsure whether or not the lad was supposed to be mentally challenged, but he seems OK in the second act, so I suspect this is just a director’s choice by Marianne Elliott and Tom Morris.

Albert attends a horse auction with his father Ted (Boris McGiver). There is bad blood between Ted and his more successful brother Arthur (T. Ryder Smith). Albert and his first cousin Billy (Matt Doyle) are also in conflict. A bidding war ensues over a “Hunter,” a half Thoroughbred, half Draft horse. Ted, more intent on besting his brother than on behaving prudently, buys the horse for a ridiculously high price. Having thus squandered the mortgage money, he then must go home to his wife.

A word here on the fine acting job done by all in the company, especially Alyssa Bresnahan as Ted’s wife Rose. It’s easy to lose good performances in flashy spectacle; it’s a tribute to the talented performers involved here that they are not upstaged by the scenery and devices around them.

Albert is given the task of raising Joey, and made aware that the horse will one day be sold to pay off the family debt. What he doesn’t expect is that his pet will be peddled to the army and sent to France, to face machine guns and barbed wire in “the war to end all wars.”

Act Two lays out the horrors of battle, to the soldiers and to their mounts. This is where I felt myself beginning to disengage. Maybe we’re just too used to the “if it bleeds, it leads” credo of local news broadcasts, replete with murder and mayhem. But after a while, a certain numbness sets in. All the loud booming noise, flashing lights, and continuing carnage forced me to detach from what was happening on stage. My “willing suspension of disbelief” got suspended. How much more effective it would be to use this action movie violence more sparingly.

The truly horrifying moments are those with minimal pyrotechnics: the sight of the broken, desperately wounded soldiers who depart as the new recruits arrive in France; the sheer visual impact of the huge machine gun; the horses deconstructing as they are demolished on the killing field; and, worst of all, the juxtaposition of horse and barbed wire. Music could have been used to great advantage during crucial battle moments; what a great place to reintroduce the gentle village folks songs.

Without a doubt, the effect that sticks most clearly in my mind is the moment when Joey goes, spectacularly, from being a colt to a full grown horse. Sheer brilliance.

Not surprisingly, that moment occurs in Act One, which is so much more focused and on point than what follows. Act Two not only goes into overkill on brutality, it also takes a strange meandering turn. Far too much time is spent depicting the anguish of The Good German, Friedrich (Peter Hermann). I had to keep reminding myself “World War One, World War One,” to even begin to care about this character, who tries to highjack the story in progress. He hates the war, he wants to get home to his daughter Sophie, he’s nice to the horses. Got it. He also protects the little French girl and her mother, who pretty much appear and then disappear, just as we think they may be on the verge of actually contributing to the plot. Friedrich is The Enemy, but The Enemy is just a pawn in the chess game of war, too, right? Genug!

What should be happening instead at this point in the production is the scene where arrogant Arthur discovers the fate of the son he has bullied into joining the army, and/or the scene where Arthur and Ted come together as brothers. The tale begins with the Cain and Able conflict that divides the Narracott family. We deserve to see a denouement on stage.

There are too many echoes in evidence of other animal myths and sagas; Black Beauty, Lassie, and Buck are all present in spirit. “Joey, phone home!” But when War Horse parades what it does best, a simple story wrapped in grand pageantry, the production achieves an extraordinary accomplishment in terms of creativity and impact.

You may love it, you may hate it, you may have your doubts. But I guarantee you won’t forget it.

Times Square Chronicles, Suzanna Bowling – “War Horse,” from the National Theatre of Great Britain now at Lincoln Center’s Vivian Beaumont Theater, is story telling in its purest form. The entire cast works as an ensemble to wrap you under their spell and you believe what has been put in front of you. The actors embody not just people but birds, geese, tanks, dead soldiers and horses; especially Joey, whose journey is brought full circle through the actors/puppeteers that bring him snorting, heaving and whinnying triumphantly to life.

“War Horse” tells of the bond between Albert (Seth Numrich) and Joey, the horse he trains and loves. When Joey is a fold, he is bought at auction, with mortgage money, by Albert’s alcoholic father, a farmer Ted Narracott (Boris McGiver), because Narracott can’t stand for his successful brother (T. Ryder Smith), bidding against him, to win yet again. Joey, born to race, must now learn to earn his keep. Albert and Joey form a friendship that braves the worst adversities. The farmer then bets his brother that Joey can plow even though he is not built for it and Albert, left without a choice, agrees to teach Joey as long as Joey will finally become his.

Joey pulls through but World War I breaks out and the farmer sells Joey behind Albert’s back to the British Army. Officer Lieutenant James Nicholls (Stephen Plunkett) promises to take care of him and shows Albert the drawings which he has been making of him and Joey riding. Albert tries to enlist but he is only 16 years old and too young. When the Lieutenant dies, Albert runs away from home and his loving mother (Alyssa Bresnahan), lies about his age, and joins the army to reunite with Joey. The horrors of war then engulf the story line.

Through life-size puppets, operated by three people, the horses come to life and humans and technology act as one. The effect is mesmerizing. You truly believe these are real horses in front of you, complete with personalities. Designed and made by Adrian Kohler with Basil Jones, for Handspring Puppet Company, these puppets are a wonder and as marvelous as what has previously been written and talked about on the news.

Directors Marianne Elliott and Tom Morris hold your attention while the sets, costumes and animated background drawings by Rae Smith add a third dimension. Adrian Sutton’s music is perfect in setting the mood as vocalist Kate Pfaffl brings her soulful sounds as a cry for us all. Nick Stafford’s adaptation of the novel by Michael Morpurgo is a dark look into war and human frailty.

Kudos to Christopher Shutt for sound; Paula Constable’s lighting, John Tams’ songs and Toby Sedgwick’s horse movement.

As for the cast, it is hard to single anyone out for they were all so talented and worked as one to make “War Horse” sublime theatre. However, Peter Hermann as a German officer and Madeline Rose Yen as the young French girl added the most heart.

“War Horse” is not light fare, so be sure to bring tissues, you will need it. There is an Arabian Proverb that states: The horse is God’s gift to mankind. “War Horse” is a gift to theatre.

LA magazine, Macho Snow Queen – The Tony Award winner for Best Play this year went to War Horse, a British import that has already been turned into a film by Steven Spielberg scheduled for release in December. Halfway through the show I couldn’t believe this was what passed for a great play. It has great style and creative production value, but as a play it suffers from clichés and conveniences that even the most inspired director cannot disguise.

Nick Stafford’s play is set at the outset of England’s involvement in World War I. The Narracott family is struggling to pay its bills. Ted Narracott (Boris McGiver) is a drunkard with an antagonistic relationship with his brother Arthur (T. Ryder Smith). So embroiled are these men that when a foal is up for auction, Ted foolishly bids 39 guineas to make sure Arthur doesn’t get it. The only person happy about this is Ted’s son, Billy (Matt Doyle). Billy and Joey (the name he gives the horse) form a very close bond. That bond is tested when Ted sells the matured horse to the Army for 100 guineas. From that moment on, Billy is determined to reunite with Joey. He even enlists in the Army. The remainder of War Horse is a journey through the hells of war. I won’t spoil what happens, but if Mr. Spielberg made the movie you can guess.

This production has two very strong suits. The actors are all deeply and wonderfully committed to the play. Mr. Doyle and Mr. McGiver particularly impressed. The other stars are the puppeteers that play the horses (there are several). The work of the puppeteers and the designers who created them (Handspring Puppet Company) is outstanding. They are remarkably imbued with charm and personality. It’s also wonderful that the actors and the horses make exits and entrances through the audience (something that will be difficult to replicate when the show appears at the Ahmanson Theatre next year).

Directors Marianne Elliott and Tom Morris begin the show with lovely restraint. However as Billy’s pursuit goes on, the terror of war becomes too irresistible to depict without the same restraint, and it is the audience who suffers for it. The sets, the sound design, the music, and more pummel us as if we’re enemies of the play. I was grateful when the show concluded because it was finally quiet again.

Ultimately though, it is the play that disappoints. There is nothing new in this boy-and-a-horse story. While the cast makes their characters come to life, they cannot make the story believable. The ending is completely contrived. It is based on a novel by Michael Morpurgo, so the blame probably ultimately goes to him. But what might work on the page certainly doesn’t work on the stage.

War Horse can join The Lion King as productions that are the reverse of the emperor’s new clothes. Both shows look amazing but can’t disguise the fact there’s nothing really there.

New York Observer, Jesse Oxfeld – “To my misfortune, I’m not homosexual,” the venerable critic John Simon once sniped on Charlie Rose. “And therefore I’m a kind of odd man out in the theatrical world, and sometimes I feel a bit aggrieved about that.” I have a different cross to bear than does Mr. Simon, but it can leave me no less aggrieved: My misfortune–and it’s one I was born with, one that apparently separates me from the vast majority of theatergoers–is that I’m not an animal person.

The Royal National production of War Horse, a smash hit in the West End that’s been anticipated in New York with panting enthusiasm, arrived last week at Lincoln Center Theater, where it received a largely drooling response.

War Horse tells the story of a British farm boy and his beloved equine, and how their idyllic if impoverished existence is upended by World War I. It involves gorgeously realized life-size horse puppets by the Handspring Puppet Company, each manipulated to stunning effect by a trio of actors. It also, almost incidentally, involves some human actors–more than a few not quite as supple as those horse puppets. They tell a by-the-numbers tear-jerker of a story about the horrors of war, the magic of noble beasts and the power of a boy’s faith.

There has been praise for the staging, which is indeed spectacular, and for the story, which is almost unbearably trite. (Directors Marianne Elliott and Tom Morris are magicians to have taken something so banal and rendered it so beautifully.) Moments before the horse, Joey, and the boy who reared him, Albert, are to be inevitably reunited in a French field hospital–Joey is about to be put down after a run-in with barbed wire; Albert, mere feet away and pining for his trusty mount, has been temporarily blinded by a tear-gas attack–a soldier draws his weapon, preparing to put the horse out of his misery. There were gasps from the audience, as if there was any doubt a happy ending was coming. This is a play for animal people

It’s too bad the story is so sadly simplistic, because Ms. Elliott’s and Mr. Morris’ stagecraft is so sublime. This play is full of literally breathtaking moments of theatrical inventiveness and stunning visuals–Joey and his fellow horses; a cavalry charge on the front; even the small, witty touch of an overeager goose on Albert’s farm, a puppet on a bicycle wheel pushed by an actor.

But, for all that, War Horse is based on a children’s story, and it remains no more emotionally complex. Not long into the second act, the tedium of the predictable story begins to weigh more heavily than the thrill of the visual creativity.

That’s when you realize you’re watching the cloying tale of a boy with an unnatural love for a half-thoroughbred.

Village Voice, Michael Feingold – War Horse offers a different kind of hoofing. War is hell, horses are noble beasts, and nothing comes alive onstage more magically than a well-manipulated puppet. Holding these truths to be self-evident, as we all do, you can have a pretty good time at War Horse, and your children will probably have an even better one, if they don’t mind its length (two hours and 40 minutes, including intermission).

Lovers of literature and drama, who might be looking for something that goes a little beyond the simple truths stated above, will find that they’ve come to the wrong shop. I assume that Michael Mopurgo’s “young-adult” novel, from which Nick Stafford has carved the script for this elaborate spectacle, allots some time to grounding its events more fully in reality, but it’s still essentially not much more than Lassie, Come Home with a horse instead of a dog, and World War I to heighten the tension. Sentimental animal stories tend to run true to form, and this one will surprise nobody: Boy gets horse, boy loses horse, but boy and horse find each other at the end, just in time for the Armistice bells to ring on cue.